Explain why seven southern states seceded from the Union shortly after Lincoln’s election in 1860.

The Southern Response

Southern Secession after Lincoln’s Election

Between November 8, 1860, when Abraham Lincoln was elected, and March 4, 1861, when he was inaugurated, the United States of America disintegrated. Lincoln’s election panicked southerners who believed that the Republican party, as a Richmond newspaper asserted, was founded for one reason: “hatred of African slavery.”

After Lincoln’s victory, South Carolina’s entire congressional delegation resigned. The state’s legislature then appointed a convention to decide whether the state should secede from the Union. Nearly all the delegates owned enslaved people. Delegate Thomas Jefferson Withers declared that the “true question for us all is how shall we sustain African slavery in South Carolina from a series of annoying attacks.”

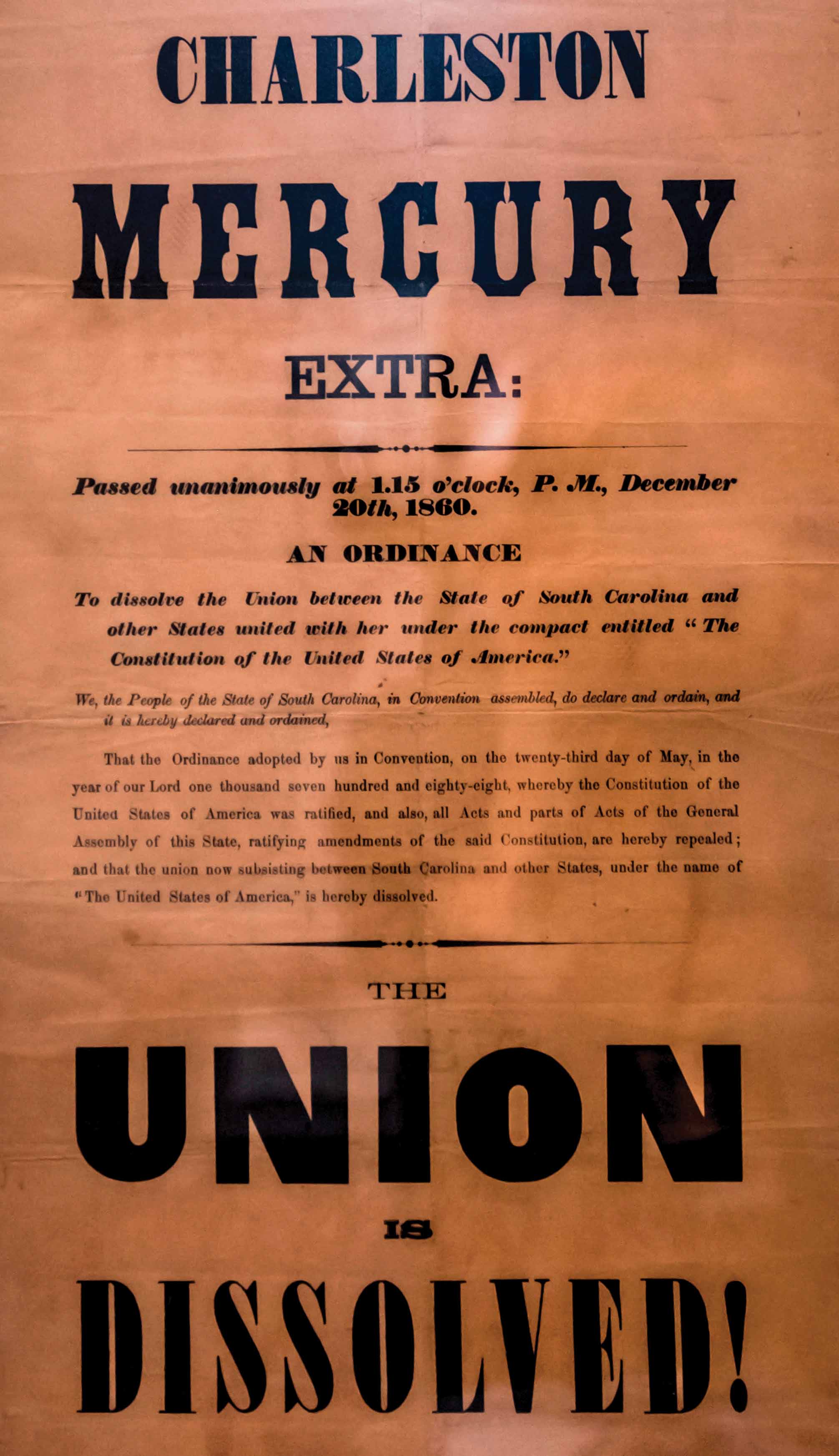

Meeting in Charleston on December 20, 1860, the special convention unanimously approved an Ordinance of Secession, explaining that Lincoln was a man “whose opinions and purposes are hostile to slavery.” Secession was a revolutionary act, the most radical step a state could take. James L. Petigru, one of the few Unionists in Charleston, claimed that those who voted for secession were lunatics. South Carolina, he quipped, “is too small to be a Republic and too large to be an insane asylum.”

As the news spread across the state, church bells rang and shops closed. “THE UNION IS DISSOLVED!” screamed the headline of the Charleston Mercury. One Unionist kept a copy of the newspaper, scribbling on the bottom of it: “You’ll regret the day you ever done this. I preserve this to see how it ends.”

President Buchanan’s Waiting Game

Other southern states soon followed South Carolina’s lead in descending into disunion. The imploding nation desperately needed a bold, decisive president to intervene. Instead it suffered under James Buchanan, who blamed the crisis on fanatical abolitionists. He declared secession illegal, then claimed that he lacked the constitutional authority to stop it. “I can do nothing,” he sighed. In the face of the president’s clueless inaction, armed southern firebrands surrounded federal forts in the seceded states.

Among the federal forts under siege was Fort Sumter, nestled on a tiny island at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. When South Carolina secessionists demanded that Major Robert Anderson, a Kentucky Unionist, surrender the fort, he refused.

On January 5, 1861, President Buchanan sent an unarmed commercial steamship, the Star of the West, to resupply Fort Sumter. As the ship approached Charleston Harbor after midnight on January 9, Confederate cannons operated by cadets from The Citadel, the state’s military college, opened fire and drove it away. It was an act of war, but Buchanan chose to ignore the attack, hoping that a compromise might avert civil war. Southern leaders, however, were not in a compromising mood. “We spit on every plan to compromise,” sneered a secessionist. The issue was no longer slavery in the territories; it was the survival of the nation. That same day, Mississippi left the Union, followed by Alabama three days later.

Secession of the Lower South (1861)

By February 1, 1861, the other states of the Lower South—Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas—had also seceded. Although their secession ordinances mentioned various grievances, they made clear that the primary reason for leaving the Union was the preservation of slavery.

On February 4, 1861, fifty representatives of the seceding states, all but one of them slave owners, met in Montgomery, Alabama, where they adopted a constitution for the Confederate States of America (CSA) modeled closely after the federal constitution. Unlike the 1787 constitution, which made no mention of God, the Rebel founders proclaimed that the CSA honored “Almighty God.” The Confederate constitution also outlawed tariffs and federal funding for internal improvements, and it enabled the president to veto specific items within the annual federal budget. The president could serve only one six-year term and could not remove federal officials without Senate approval.

The CSA was to have only an agricultural economy. As one of its framers, the South Carolina–born Texan Louis Wigfall, insisted, “We want no manufactures: we desire no trading, no mechanical or manufacturing classes” of workers.

Perhaps most important, the constitution mandated that “the institution of negro slavery, as it now exists in the Confederate States, shall be recognized and protected” by the new government.

The delegates unanimously elected as president Mississippi’s Jefferson Finis Davis (his middle name chosen because he was the last of ten children). Davis, a West Point graduate who had been a much-decorated officer in the Mexican-American War, became a U.S. senator and then served as secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce. It took him five days by train to reach Montgomery. Along the way, he delivered twenty-five speeches. In Jackson, Mississippi, he claimed that if “only the North would recognize our independence, all would be well.” Still, at every stop, he told his cheering listeners to prepare for “a long and bloody conflict.”

Georgia’s Alexander H. Stephens, Davis’s vice president, told supporters that the Confederacy was founded to sustain the slave system upon which the southern economy depended. The new nation, he said, embodied “the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior [White] race, is his natural and normal condition.”

Compromise Effort Fails

President-elect Lincoln still assumed that the southerners were bluffing. Members of Congress, meanwhile, sought to avert civil war. On December 18, 1860, slave owner John J. Crittenden of Kentucky, the oldest member of the Senate, had suggested that slavery be allowed in the western territories south of the 1820 Missouri Compromise line (36°30´ parallel) and be guaranteed to continue where it already existed. Lincoln, however, opposed any plan that would expand slavery westward, and the Senate defeated the Crittenden Compromise, 25–23.

Lincoln’s Inauguration

In mid-February 1861, Abraham Lincoln boarded a train in Springfield, Illinois, headed to Washington, D.C., for his inauguration. Alerted to a plot to assassinate him when he changed trains in Baltimore, federal officials had Lincoln wear a disguise and board a secret train in Pennsylvania. The train carrying Lincoln slipped through Baltimore unnoticed.

In his inaugural address on March 4, the most highly anticipated speech in U.S. history, the fifty-two-year-old Lincoln repeated his pledge not “to interfere with the institution of slavery in the states where it exists” because he had no authority to do so. The immediate question, however, had shifted to secession. Lincoln insisted that “the Union of these States is perpetual,” and therefore the notion of a Confederate nation was a fiction. No state, he stressed, “can lawfully get out of the Union.” He pledged to defend “federal forts in the South,” such as Fort Sumter, but beyond that “there [would] be no invasion, no using of force against or among the people anywhere.”

In closing, Lincoln appealed for regional harmony:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

Southerners were not impressed. A North Carolina newspaper warned that Lincoln’s speech made civil war “inevitable.” The editor of the Richmond Enquirer dismissed the new president as a “fanatic” eager to bring on the “horrors of civil war.” A New Orleans newspaper blamed northern voters, for by electing Lincoln, they had “perpetuated a deliberate, cold-blooded insult and outrage on the people of the slaveholding states.”

Both sides assumed that if fighting erupted, it would be over quickly and that their daily lives would go on as usual. That perception would soon be proven terribly wrong.

The End of the Waiting Game

On March 5, 1861, his first day in office, President Lincoln found a letter on his desk from Major Robert Anderson, the army commander at Fort Sumter. Anderson reported that his men had enough food for only a few weeks and that the Confederates were encircling the fort with a “ring of fire.”

On April 4, Lincoln ordered unarmed ships to resupply the sixty-nine soldiers at Fort Sumter. His Confederate counterpart, Jefferson Davis, resolved to stop any such effort. On April 11, Confederate general Pierre G. T. Beauregard, who had studied under Major Anderson at West Point, demanded that his former professor surrender Fort Sumter. Anderson refused. At four-thirty in the morning darkness of April 12, Confederates began firing on Fort Sumter. After some thirty-four hours, his ammunition exhausted, Anderson lowered the “Stars and Stripes.”

The Confederate attack on Fort Sumter changed everything. It “has made the North a unit,” New York Democratic congressman Daniel Sickles wrote. “We are at war with a foreign power.” On April 15, the Charleston Mercury newspaper ran a simple headline: “Lincoln Declares War.” A civil war of unimagined horrors had begun. “War begins where reason ends,” said the African American abolitionist Frederick Douglass, and the South’s outsized fears confirmed the logic of his statement.