![]() Native American Diversity

Native American Diversity

Why were there so many diverse human societies in the Americas before Europeans arrived?

EARLY CULTURES IN THE AMERICAS

Over many centuries, as the climate warmed, days grew so much hotter that many of the largest mammals—mammoths, mastodons, giant bison—became extinct. Hunters then began stalking smaller, yet more-abundant mammals: deer, antelope, elk, moose, and caribou. Over time, the Ancient Indians adapted to their varied environments—coastal forests, grassy plains, southwestern deserts, eastern woodlands. Some continued to hunt with spears and, later, bows and arrows; others fished or trapped small game. Some gathered wild plants and herbs and collected acorns and seeds, while others farmed. Most did some of each.

By about 7000 B.C.E. (before the Common Era), hunter-gatherer societies began transforming themselves into farming cultures, supplemented by seasonal hunting and gathering. Agriculture provided more nutritious food, which accelerated population growth and enabled once nomadic people to settle in villages. Indigenous peoples became expert at growing plants that would become the primary food crops of the hemisphere, chiefly maize (corn), beans, and squash, but also chili peppers, avocados, and pumpkins.

Maize-based societies viewed corn as the “gift of the gods” because it provided many essential needs. They made hominy by soaking dried kernels of corn in a mixture of water and ashes and then cooking it. They used corn cobs for fuel and the husks to fashion mats, masks, and dolls. They also ground the kernels into cornmeal, which could be mixed with beans to make protein-rich succotash.

THE MAYA, INCAS, AND MEXICAS

In Middle America (Mesoamerica, what is now Mexico and Central America), agriculture supported the development of sophisticated communities complete with gigantic temple-topped pyramids, palaces, and bridges.

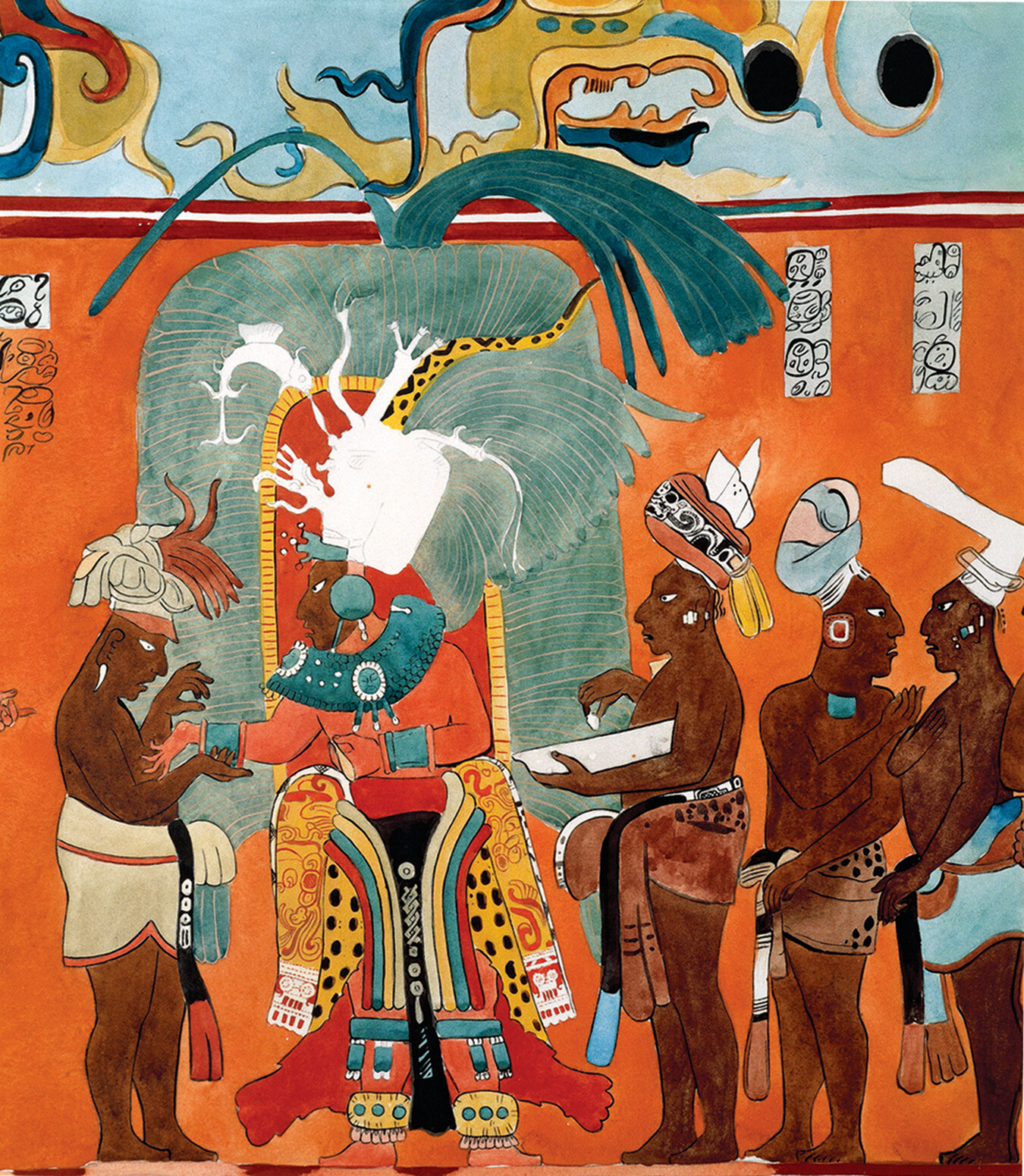

The Maya, who dominated Central America for more than 600 years, worshipped more than a hundred gods and developed a written language and elaborate works of art and architecture. They used mathematics and astronomy to create a yearly calendar more accurate than the one Europeans were using at the time of Columbus. Maya civilization featured sprawling cities, terraced farms, and spectacular pyramids.

In about 900 C.E., however, the Maya culture collapsed. Why it disappeared remains a mystery. Was its demise the result of civil wars or ecological catastrophe—drought, famine, disease, crop failure? The Maya destroyed much of the rain forest, upon whose fragile ecosystem they depended. As an archaeologist has explained, “Too many farmers grew too many crops on too much of the landscape.” Deforestation led to hillside erosion and a catastrophic loss of nutrient-rich farmland.

Overpopulation added to the strain on Maya society, prompting civil wars. The Maya eventually succumbed to the Toltecs, who conquered most of the region in the tenth century. Around 1200 C.E., however, the Toltecs mysteriously withdrew after a series of droughts, fires, and invasions.

THE INCAS Much farther south, many diverse people speaking at least twenty different languages made up the sprawling Inca Empire. By the fifteenth century, the Incas’ vast realm stretched some 2,500 miles along the Andes Mountains in the western part of South America. It featured irrigated farms, stone buildings, and interconnected networks of roads paved with stones.

THE MEXICAS (AZTECS) During the thirteenth century, the nomadic Mexicas (Me-SHEE-kas) began drifting southward from northwest Mexico. (They were not called Aztecs until 1821, when Mexico gained its independence from Spain.) Disciplined and imaginative, the Mexicas seized control of the central highlands, where they built the spectacular city of Tenochtitlán (place of the stone cactus) on an island in Lake Tetzcoco, at the site of present-day Mexico City.

Tenochtitlán would become one of the grandest cities in the world. It served as the capital of a sophisticated Mexica Empire ruled by a powerful emperor and divided into two social classes: nobles, warriors, and priests (about 5 percent of the population), and the free commoners—merchants, artisans, farmers, and enslaved peoples.

When the Spanish invaded Mexico in 1519, they found a vast Mexica Empire connected by a network of roads serving 371 city-states organized into 38 provinces. Towering stone temples, paved avenues, thriving marketplaces, and some 70,000 adobe (sunbaked mud) huts dominated Tenochtitlán.

As their empire expanded across central and southern Mexico, the Mexicas (Aztecs) developed elaborate societies supported by sophisticated legal and political systems. Their cities boasted lively markets and busy merchants and featured beautiful gardens and relaxing spas. The Mexicas practiced efficient new farming techniques, including terracing of fields, crop rotation, large-scale irrigation, and other engineering marvels. Their arts and architecture were magnificent.

Mexica rulers claimed godlike qualities, and nobles, priests, and warrior-heroes dominated the social system. The emperor’s palace had 100 rooms and baths replete with statues, gardens, and a zoo; the aristocracy lived in large stone dwellings, practiced polygamy (multiple wives), and were exempt from manual labor. Like most agricultural peoples, the Mexicas worshipped multiple gods. Their religious beliefs focused on the interconnection between nature and human life and the sacredness of natural elements—the sun, moon, stars, rain, mountains, rivers, and animals. They were obliged to feed the gods human hearts and blood. As a consequence, the Mexicas, like most Mesoamerican societies, regularly offered thousands of live human sacrifices to the gods.

- What were the major pre-Columbian civilizations?

- What factors caused the demise of the Maya civilization?

- What was the importance of the Mexica city of Tenochtitlán?

In elaborate weekly rituals, captured warriors or virgin girls would be daubed with paint, given a hallucinatory drug, and marched to the temple platform, where priests cut out their beating hearts and offered them to the sun god. The constant need for human sacrifices fed the Mexicas’ relentless warfare against other indigenous groups. A Mexica song celebrated their warrior code: “Proud of itself is the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlán. Here no one fears to die in war. This is our glory.” Warfare, therefore, was a sacred activity. Gradually, the Mexicas conquered many neighboring societies, forcing them to make payment of goods and labor as tribute to the empire.

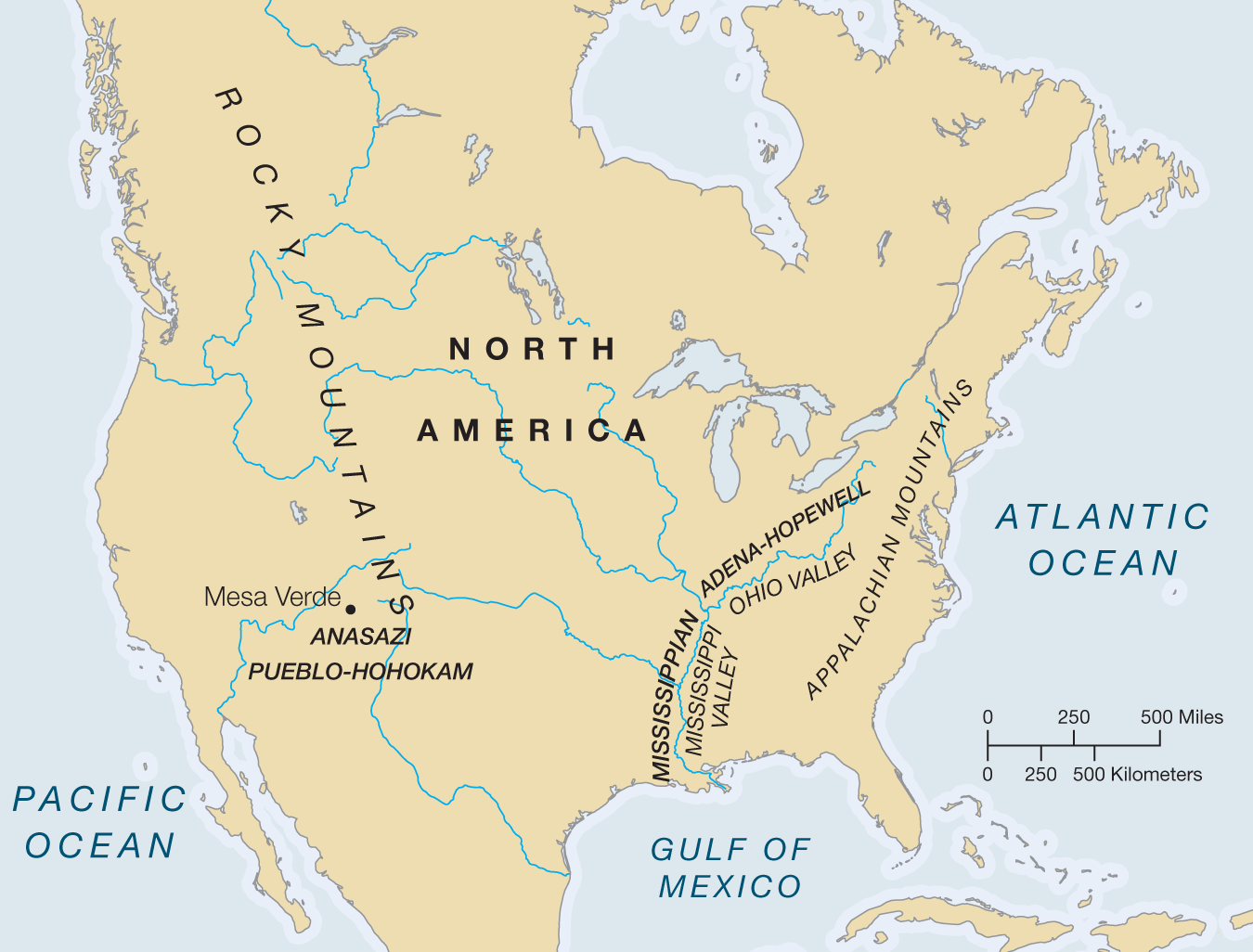

NORTH AMERICAN CIVILIZATIONS AROUND 1500

North of Mexico, in the present-day United States, many indigenous societies blossomed in the early 1500s. Over the centuries, small kinship groups (clans) had coalesced to form larger bands involving hundreds of people. The bands evolved into much larger regional groups, or nations, whose members spoke the same language. Although few indigenous societies had an alphabet or written language, they all developed rich oral traditions that passed spiritual myths and social beliefs from generation to generation.

Like the Mexicas, most indigenous peoples in the Americas believed in godlike “spirits.” To the Sioux, God was Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit. The Navajos believed in the Holy People: Sky, Earth, Moon, Sun, Thunders, and Winds. Many Native Americans also believed in ghosts, who acted as their bodyguards in battle.

The importance of hunting to many Indian societies helped nurture a warrior ethic in which courage in combat was the highest virtue. War dances the night before a hunt or battle invited the spirits to unleash magical powers. Native American warfare mostly consisted of small-scale raids intended to enable individual warriors to demonstrate their courage rather than to seize territory or destroy villages. Casualties were minimal. The taking of captives to be sacrificed or enslaved often signaled victory.

For all their similarities, the indigenous peoples of North America developed markedly different ways of life. In North America alone in 1492, when the first Europeans arrived, there were perhaps 8 million native peoples organized into 240 societies. By comparison, Great Britain had about 2 to 3 million people.

These Native Americans practiced diverse customs and religions and developed varied economies. Some wore clothes they wove or made using animal skins, and others wore nothing but colorful paint, tattoos, or jewelry. Some lived in stone houses, others in circular timber wigwams or bark-roofed longhouses. Still others lived in sod-covered or reed-thatched lodges, or portable tipis made from animal skins. Some cultures built stone pyramids graced by ceremonial plazas, and others constructed enormous burial or ritual mounds topped by temples.

Few North American Indian societies permitted absolute rulers. Nations had chiefs, but the “power of the chiefs,” reported an eighteenth-century British trader, is often “an empty sound. They can only persuade or dissuade the people by the force of good-nature and clear reasoning.” Likewise, Henry Timberlake, a British soldier, explained that the Cherokee government, “if I may call it a government, which has neither laws nor power to support it, is a mixed aristocracy and democracy, the chiefs being chosen according to their merit in war.”

Native Americans owned land in common rather than individually as private property. Men were hunters, warriors, and leaders. Women tended children; made clothes, blankets, jewelry, and pottery; cured and dried animal skins; wove baskets; built and packed tipis; and grew, harvested, and cooked food.

When the men were away hunting or fighting, women took charge of village life. Some Indian nations, like the Cherokee and the Five Nation League of the Iroquois (comprised of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca Nations), gave women political power. The women “are much respected,” a French priest reported on the Iroquois. “The Elders decide no important affair without their advice.”

THE SOUTHWEST The often hot and dry Southwest (what is now Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah) featured a landscape of high mesas, deep canyons, vast deserts, long rivers, and snow-covered mountains. The Hopis, Zunis, and others still live in the multistory adobe cliffside villages (called pueblos by the Spanish), which were erected by their ancient ancestors.

About 500 C.E. (Common Era), the Hohokam (“those who have vanished”) people migrated from Mexico northward to southern and central Arizona, where they built extensive canals to irrigate crops. They also crafted decorative pottery and turquoise jewelry.

The most widespread of the Southwest pueblo cultures were the Anasazi (Ancestral Pueblos), or Basketmakers. Unlike the Mexicas and Incas, however, Ancestral Pueblo society did not have a rigid class structure. The Ancestral Pueblos engaged in warfare only as a means of self-defense, and the religious leaders and warriors worked much as the rest of the people did.

THE NORTHWEST Along the narrow coastal strip running up the densely forested northwest Pacific coast, shellfish, salmon, seals, whales, deer, and edible wild plants were abundant. Here, there was little need to rely on farming. Many of the Pacific Northwest peoples, such as the Haida, Kwakiutl, and Nootka, needed to work only two days to provide enough food for a week.

The Pacific coast cultures developed intricate religious rituals and sophisticated woodworking skills. They carved towering totem poles featuring decorative figures of animals and other symbolic characters. For shelter, they built large, earthen-floored, cedar-plank houses up to 500 feet long, where groups of families lived together. They also created sturdy, oceangoing canoes made of hollowed-out tree trunks—some large enough to carry fifty people. Socially, they were divided into slaves, commoners, and chiefs.

THE GREAT PLAINS The many tribal nations living on the Great Plains, a vast, flat land west of the Mississippi River, included the Arapaho, Blackfeet, Cheyenne, Comanche, Crow, Apache, and Sioux. As nomadic hunter-gatherers, they tracked herds of bison (buffaloes) across a sea of grassland, collecting seeds, nuts, roots, and berries as they roamed.

For all their differences, Native Americans developed a religious worldview distinctly different from the Christian perspective of Europeans. At the center of most hunter-gatherer religions is the idea that human beings are related to all living things, including natural objects: trees, rocks, rivers, mountains. As the Navajos sing, “All my surroundings are blessed as I found it.” By contrast, the Bible portrays believers as separate from and superior to the natural world, encouraging them to exercise their “dominion” over the land and water.

THE MISSISSIPPIANS East of the Great Plains, in the vast woodlands reaching from the Mississippi River to the Atlantic Ocean, several “mound-building” cultures prospered. Between 700 B.C.E. and 200 C.E., the Adena and later the Hopewell societies developed communities in the Ohio valley. The Adena-Hopewell cultures grew corn, squash, beans, and sunflowers, as well as tobacco for smoking. They left behind enormous earthworks and elaborate burial mounds shaped like snakes, birds, and other animals.

Like the Adena, the Hopewell developed an extensive trading network with other Indian societies from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada, exchanging exquisite carvings, metalwork, pearls, seashells, copper ornaments, bear claws, and jewelry. By the sixth century, however, the Hopewell culture disappeared, giving way to a new phase of development east of the Mississippi River, the Mississippian culture.

- What were the three dominant pre-Columbian civilizations in North America?

- Where was the Adena-Hopewell culture centered?

- How was the Mississippian civilization similar to that of the Maya or Mexicas?

- What made the Anasazi culture different from the other North American cultures?

The Mississippians were corn-growing peoples who built substantial agricultural towns around central plazas and temples and developed a far-flung trading network that extended to the Rocky Mountains. Their ability to grow large amounts of corn in the fertile flood plains spurred rapid population growth around regional centers. The largest of these advanced regional centers, called chiefdoms, was Cahokia (600–1300 C.E.), in southwest Illinois, near the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers (across from what is now St. Louis).

The Cahokians constructed an enormous farming settlement with monumental public buildings, spacious ceremonial plazas, and more than eighty flat-topped earthen mounds with thatch-roofed temples on top. At the height of its influence, Cahokia hosted 15,000 people on some 3,200 acres.

Cahokia, however, vanished around 1400. Its collapse remains a mystery, but the overcutting of trees to make fortress walls may have set in motion ecological changes that doomed the community when a massive earthquake struck. The loss of trees led to widespread flooding and the erosion of topsoil, which forced residents to seek better land across the Midwest and into what is now the American South.

EASTERN WOODLAND PEOPLES AND EUROPEAN CONTACT After the collapse of Cahokia, the Eastern Woodland peoples spread along the Atlantic Seaboard from Maine to Florida and along the Gulf Coast to Louisiana. They included three groups distinguished by their different languages: the Algonquian, the Iroquoian, and the Muskogean. These were the indigenous societies that Europeans would first encounter when they arrived in North America.

The Algonquian-speaking peoples stretched westward from the New England Seaboard to lands along the Great Lakes and into the Upper Midwest and south to New Jersey, Virginia, and the Carolinas. They lived in small, round wigwams or in multifamily longhouses surrounded by a palisade, a tall timber fence to defend against attacks. Their villages typically ranged in size from 500 to 2,000 people.

The Algonquians along the Atlantic coast were skilled at fishing and gathering shellfish; the inland Algonquians excelled at hunting. All Algonquians foraged for wild food (nuts, berries, and fruits) and practiced agriculture. They annually burned the underbrush in dense forests to improve soil fertility and provide grazing room for deer. In the spring, many Indian nations cultivated corn, beans, and squash, plants that they called the “three sisters” because they thrived together. The cornstalks provided support for the bean tendrils, and the beans pulled nitrogen out of the air and dispersed it through the soil to benefit all three companion plants. The large leaves generated by the squash provided shade for the corn and bean plants.

West and south of the Algonquians were the powerful Iroquoian-speaking peoples (the Seneca, Onondaga, Mohawk, Oneida, and Cayuga Nations, as well as the Cherokee and Tuscarora). Their lands spread from upstate New York southward through Pennsylvania and into the Carolinas and Georgia. The Iroquois were farmer/hunters who lived in extended family groups (clans), sharing bark-covered longhouses in towns of 3,000 or more people. The oldest woman in each longhouse served as the “clan mother.”

Unlike the Algonquian culture, in which men were dominant, women held the critical leadership roles in the Iroquoian culture. As an Iroquois elder explained, “In our society, women are the center of all things. Nature, we believe, has given women the ability to create; therefore, it is only natural that women be in positions of power to protect this function.” Iroquois men and women operated in separate social domains. No woman could be a chief; no man could head a clan. Women selected the chiefs, controlled the distribution of property, supervised the enslaved, and planted and harvested the crops. They also arranged marriages. After a wedding ceremony, the man moved in with his wife’s family. In part, the Iroquoian matriarchy reflected the frequent absence of Iroquois men, who as skilled hunters and traders traveled extensively for long periods.

The third major Native American group in the Eastern Woodlands included the peoples along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico who farmed and hunted and spoke the Muskogean language: the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Natchez, Apalachee, and Timucua. Like the Iroquois, they were often matrilineal societies, meaning that ancestry flowed through the mother’s line, but they had a more rigid class structure. The Muskogeans lived in towns arranged around a central plaza. Many of their thatch-roofed houses had no walls because of the mild winters and hot, humid summers.

Over thousands of years, the native North Americans had displayed remarkable resilience, adapting to the uncertainties of frequent warfare, changing climates, and varying environments. They would display similar resilience against the challenges created by the arrival of Europeans. In the process of adapting their heritage and ways of life to unwanted new realities, the Native Americans played a significant role in shaping America.

Glossary

- maize (corn)

- The primary grain crop in Mesoamerica, yielding small kernels often ground into cornmeal. Easy to grow in a broad range of conditions, it enabled a global population explosion after being brought to Europe, Africa, and Asia.

- Mexicas

- Otherwise known as Aztecs, a Mesoamerican people of northern Mexico who founded the vast Aztec Empire in the fourteenth century, later conquered by the Spanish under Hernán Cortés in 1521.

- Mexica Empire

- The dominion established in the fourteenth century under the imperialistic Mexicas, or Aztecs, in the valley of Mexico.

- burial mounds

- A funereal tradition, practiced in the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys by the Adena-Hopewell cultures, of erecting massive mounds of earth over graves, often shaped in the designs of serpents and other animals.

- Cahokia

- The largest chiefdom of the Mississippian Indian culture located in present-day Illinois and the site of a sophisticated farming settlement that supported up to 15,000 inhabitants.

- Eastern Woodland peoples

- Various Native American societies, particularly the Algonquian, Iroquoian, and Muskogean regional groups, who once dominated the Atlantic seaboard from Maine to Louisiana.