![]() English Colonies in the Chesapeake Region

English Colonies in the Chesapeake Region

What were the characteristics of the English colonies in the Chesapeake region, the Carolinas, the middle colonies—Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware—and New England prior to 1700?

SETTLING THE AMERICAN COLONIES

During the seventeenth century, all but one of England’s North American colonies—Georgia—were founded. The colonists were energetic, courageous, and often desperate and ruthless people willing to risk their lives in hopes of improving them. Many of those who were jobless and landless in England would find their way to America, a place already viewed as a land of opportunity—and danger.

THE CHESAPEAKE REGION

In 1606, King James I gave his blessing to a joint-stock enterprise called the Virginia Company. It was owned by merchant investors seeking to profit from the gold and silver they hoped to find. The king also ordered the Virginia Company to bring the “Christian religion” to the Indians, who “live in darkness and miserable ignorance of the true knowledge and worship of God.” As was true of many colonial ventures, however, such missionary activities were quickly dropped in favor of making money.

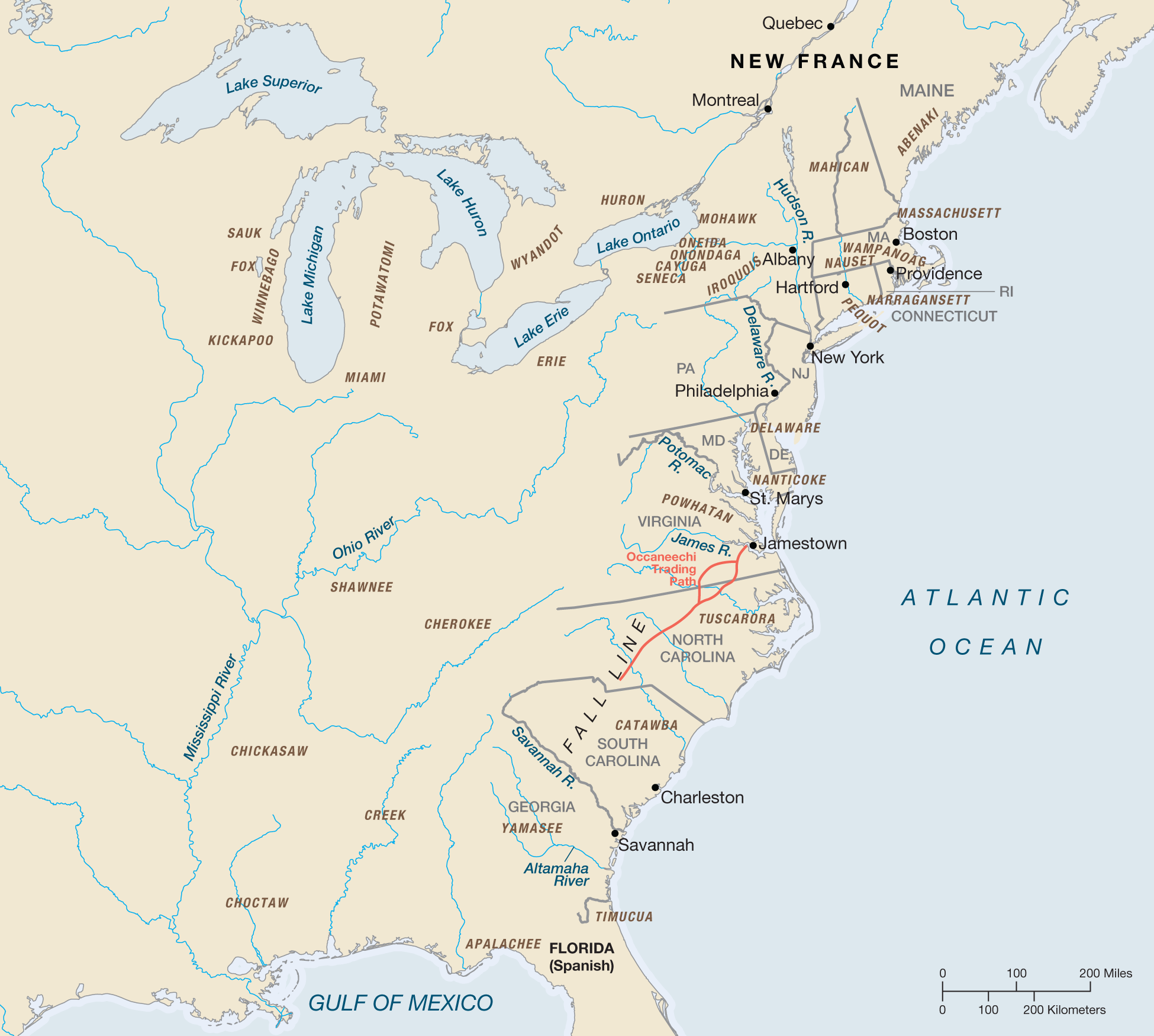

JAMESTOWN In December 1606, the Virginia Company sent to America three ships carrying 104 colonists, all men and boys. In May 1607, after five storm-tossed months at sea, they reached Chesapeake Bay, which extends 200 miles along the coast of Virginia and Maryland. To avoid Spanish raiders, the colonists chose to settle about forty miles inland along a large river. They called it the James, in honor of the king, and named their settlement James Fort, later renamed Jamestown.

On a marshy peninsula fed by salty water and swarming with mosquitos, the colonists built a fort, huts, and a church. They struggled to find enough to eat, for most of them were either townsmen unfamiliar with farming or “gentleman” adventurers who despised manual labor. Were it not for the food acquired or stolen from neighboring Indians, Jamestown would have collapsed.

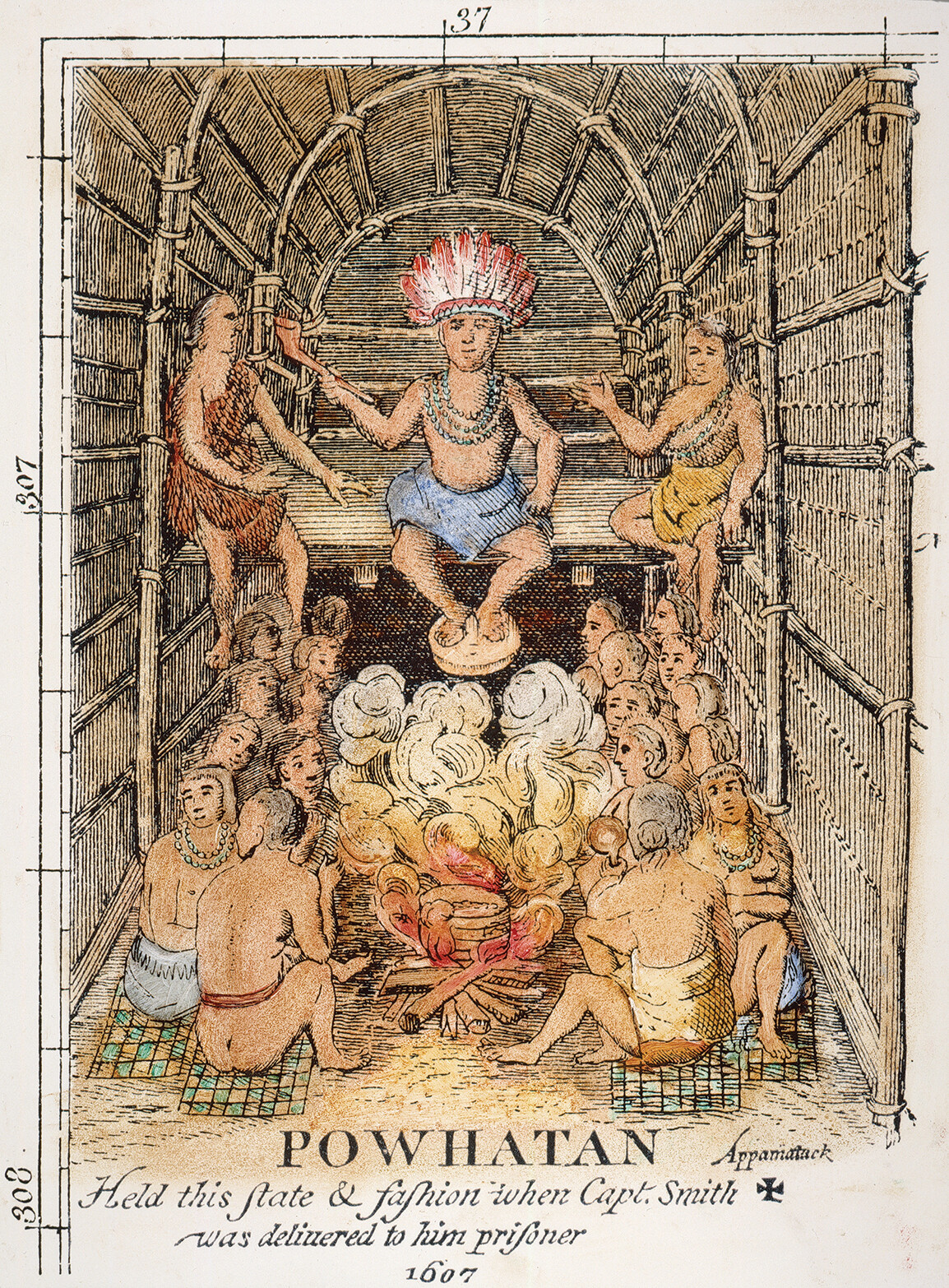

The Powhatan Confederacy dominated the indigenous peoples of the Chesapeake region. Chief Powhatan ruled several hundred villages (of about a hundred people each) organized into thirty chiefdoms in eastern Virginia. The Powhatans were farmers adept at growing corn. They lived in oval-shaped houses framed with bent saplings and covered with bark or mats.

Chief Powhatan lived in a massive lodge on the York River, not far from Jamestown. Forty bodyguards protected him, and a hundred wives bore him scores of children. Powhatan forced the rival peoples he had conquered to give him most of their corn. He also traded with the English colonists, exchanging corn and hides for hatchets, swords, and muskets. However, Powhatan realized too late that the newcomers planned to seize his lands and enslave his people.

POCAHONTAS One of the most remarkable Indians near Jamestown was Pocahontas, the favorite daughter of Chief Powhatan. In 1607, then only eleven years old, she figured in perhaps the best-known story of the settlement, her plea for the life of Captain John Smith. After Indians captured Smith and a group of Englishmen trespassing on their land, Chief Powhatan ordered his warriors to kill Smith. As they prepared to smash Smith’s skull, young Pocahontas made a dramatic appeal for his life. She convinced her father to release him in exchange for muskets, hatchets, beads, and trinkets.

Schoolchildren still learn the story of Pocahontas and John Smith, but through the years the story’s facts have become distorted or even falsified. Pocahontas and John Smith were friends, not lovers. Moreover, she saved Smith on more than one occasion, before she was kidnapped by English settlers eager to blackmail Powhatan.

Pocahontas, however, surprised her English captors by choosing to join them. She embraced Christianity, was baptized and renamed Rebecca, and fell in love with John Rolfe, a twenty-eight-year-old widower who introduced tobacco to Jamestown. After their marriage, they moved in 1616 with their infant son, Thomas, to London. There the young princess drew excited attention from the royal family and curious Londoners. Just months after arriving, however, Lady Rebecca, only twenty years old, contracted a lung disease and died.

HARD TIMES The Jamestown settlers had expected to find gold and silver, friendly Indians, and comfortable living in America. They instead found disease, drought, starvation, violence, and death. Virtually every colonist fell ill within a year. “Our men were destroyed with cruel diseases,” a survivor wrote, “but for the most part they died of mere famine.”

Fortunately for the Virginia colonists, they found a bold leader in Pocahontas’s friend, Captain John Smith, a twenty-seven-year-old mercenary (soldier for hire). At five feet three inches, he was a sturdy runt of a man, full of tenacity, courage, and confidence. With the colonists on the verge of starvation, Smith imposed strict military discipline and forced all to work if they wanted to eat. Through Smith’s often brutal efforts, Jamestown survived—but only barely.

- Why did European settlement lead to the expansion of hostilities among the Indians?

- What were the consequences of the trade and commerce between the English settlers and the southern Indigenous peoples?

- How were the relationships between the settlers and the members of the Iroquois League different from those between settlers and Indians in other regions?

During the winter of 1609–1610, the food supply again ran out, and most of the colonists died from “the sharp prick of hunger.” Desperate settlers consumed their horses, cats, and dogs, then rats, mice, and snakes. A few “dug up dead corpses out of graves” and ate them. One hungry man killed, salted, and ate his pregnant wife. Horrified by such cannibalism, his fellow colonists executed him. Still, the cannibalism continued. “So great was our famine,” Smith wrote, “that a savage we slew and buried, the poorer sort [of colonists] took him up again and ate him.”

When the colonists discovered no gold or silver, the Virginia Company shifted its focus to the sale of land, which would rise in value as the colony grew in population. The company recruited more settlers, including a few courageous women, by promising that Virginia would “make them rich.” In late May 1610, Sir Thomas Gates, a prominent English soldier and sea captain, brought some 150 new colonists to Jamestown. They found the settlement in shambles. The fort’s walls and settlers’ cabins had been used as firewood, and the church was in ruins. Of the original 104 Englishmen, only 38 had survived. They greeted the newcomers by shouting, “We are starved! We are starved!”

After nearly abandoning Jamestown to return to England, Gates led the rebuilding of the settlements and imposed a strict system of laws. The penalties for running away, for example, included shooting, hanging, or burning. Gates also ordered the colonists to attend church services on Thursdays and Sundays. Religious uniformity became a crucial instrument of public policy and civic duty in colonial Virginia.

Over the next several years, the Jamestown colony limped along until at last the settlers found a profitable crop: tobacco. Smoking had become a widespread habit in Europe, and tobacco plantations flourished on Caribbean islands. In 1612, settlers in Virginia began growing tobacco for export to England, using seeds brought from South America. By 1620, the colony was shipping 50,000 pounds of tobacco each year; by 1670, Virginia and Maryland were exporting 15 million pounds annually.

Despite its labor-intensive demands, the growing of tobacco became the most profitable enterprise in colonial Virginia and Maryland. Growing tobacco, however, quickly depleted the soil of nutrients, so large-scale tobacco farming required increasingly more land for planting and more laborers to work the fields. Much like sugar and rice, tobacco would be one of the primary crops that would drive the demand for indentured servants and enslaved Africans.

In 1618, Sir Edwin Sandys, a prominent member of Parliament, became head of the Virginia Company. He launched a new headright (land grant) policy: anyone who bought a share in the company and could pay for passage to Virginia could have fifty acres upon arrival and fifty more for each servant he brought along. The following year, the company promised that the settlers would have all the “rights of Englishmen.” Those rights included a legislature elected by the people. This was a crucial development, for the English had long enjoyed the broadest civil liberties and the least intrusive government in Europe. Now the colonists in Virginia were to enjoy the same rights.

In 1619, the Virginia Company created the first elected legislature in the Western Hemisphere. The House of Burgesses, modeled after Parliament, would meet at least once a year to make laws and decide on taxes. It included the governor, his four councilors, and twenty-two burgesses elected by free White male property owners over the age of seventeen. The word burgess derived from the medieval burgh, meaning a town or community. The House of Burgesses represented the first experiment with representative government in the American colonies.

The year 1619 was eventful in other respects. The settlement had outgrown James Fort and was formally renamed Jamestown. Also in that year, a ship arrived with ninety young women. Men rushed to claim them as wives by providing 125 pounds of tobacco to cover the cost of their trip.

Still another significant development occurred in 1619 when an English ship called the White Lion stopped at Point Comfort, Virginia, near Jamestown, and unloaded “20 and odd Negars,” the first enslaved Africans known to have reached the British American mainland. Portuguese slave traders had captured them in Angola in West Africa. On their way to Mexico, the Africans were seized by the marauding White Lion known to raid Portuguese and Spanish ships.

The arrival of Africans in Virginia marked the beginning of two and a half centuries of slavery in British North America. They were the first of some 450,000 Africans who would be seized and shipped to the mainland colonies. Overall, Europeans would transport 12.5 million enslaved Africans to the Western Hemisphere, 15 percent of whom died in transit. The majority were delivered to Brazil and the Caribbean “sugar” islands—Barbados, Cuba, Jamaica, and others. There the heat, humidity, and awful working conditions brought an early death to most enslaved workers. It is in this sense that institutionalized slavery is said to be the “original sin” committed by the English who settled the American colonies.

The year 1619 thus witnessed the terrible irony of the Virginia colony establishing the principle of representative government (the House of Burgesses) while enslaving Africans. From that point on, color-based slavery, America’s original sin, would corrode the ideals of liberty and equality that would inspire the fight for independence.

By 1624, some 8,000 English men, women, and children had migrated to Jamestown, although only 1,132 had survived, and many of them were in “a sickly and desperate state.” In 1622 alone, nearly 1,000 colonists died of disease or were victims of Indian attacks.

In 1624, the Virginia Company declared bankruptcy, and Virginia was converted from a joint-stock company to a royal colony controlled by the government. The settlers were now free to own property and start businesses. The king, however, would appoint their governors. Governor William Berkeley, who arrived in 1642, presided over the colony’s rapid growth for most of the next thirty-five years. Tobacco prices surged, and wealthy planters began to dominate social and political life.

The Jamestown experience did not invent America, but the colonists’ gritty will to survive, their mixture of greed and piety, and their exploitation of both Indians and Africans formed the model for many of the struggles, achievements, and hypocrisies that would come to define the American colonies and the American nation.

MARYLAND In 1634, ten years after Virginia became a royal colony, a neighboring settlement appeared on the northern shore of Chesapeake Bay. Named Maryland in honor of Henrietta Maria, the Catholic wife of King Charles I, its 12 million acres were granted to Sir George Calvert, Lord Baltimore. It thereby became the first proprietary colony—that is, an individual owned it—as opposed to a joint-stock company owned by investors.

Calvert, a Roman Catholic, asked the king to grant him a colony north of Virginia. Calvert, however, died before the king could act. So the charter went to Calvert’s son Cecilius, the second Lord Baltimore, who founded the colony.

Cecilius Calvert envisioned Maryland as a refuge for English Catholics. Yet he also wanted the colony to be profitable and to avoid antagonizing Protestants. To that aim, he instructed his brother, Leonard, the colony’s first governor, to ensure that Catholic colonists did not stir up trouble with Protestants. They must worship in private and remain “silent” about religious matters.

In 1634, the Calverts planted the first settlement in coastal Maryland at St. Mary’s, near the mouth of the Potomac River, about eighty miles north of Jamestown. Cecilius sought to avoid the mistakes made at Jamestown. He recruited colonists made up of families intending to stay, rather than single men seeking quick profits. He and his brother also wanted to avoid the extremes of wealth and poverty that had developed in Virginia. To do so, they bought land from the Indians and provided 100 acres to each adult settler and 50 more for each child. The Calverts also promoted the “conversion and civilizing” of the “barbarous heathens.” Jesuit priests served as missionaries to the Indians. To avoid the frequent Indian wars suffered in Virginia, the Calverts pledged to purchase land from the Native Americans rather than take it by force.

- Why did Lord Baltimore create Maryland?

- How was Maryland different from Virginia?

- What were the main characteristics of Maryland’s 1632 charter?

Still, the early years in the Maryland colony were as difficult as in Virginia. Nearly half the colonists died before reaching age twenty-one. Some 34,000 colonists would arrive between 1634 and 1680, but in 1680 the colony’s White population was only 20,000. The Calverts ruled with the consent of the freemen (all property holders). Yet they could not attract enough Roman Catholics to develop a self-sustaining economy. Most who came to the colony were Protestants. In the end, Maryland succeeded more quickly than Virginia because of its focus on growing tobacco from the start. Its long coastline along the Chesapeake Bay gave planters easy access to shipping.

Despite the Calverts’ caution “concerning matters of religion,” Catholics and Protestants feuded as violently as they had in England. When Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans took control in England and executed King Charles I in 1649, Cecilius Calvert feared he might lose his colony. To avoid such a catastrophe, he appointed Protestants to the colony’s ruling council. He also wrote the Toleration Act (1649), a revolutionary document that welcomed all Christians, regardless of their denomination or beliefs. (It also promised to execute anyone who denied the divinity of Jesus.)

Still, Calvert’s efforts were not enough to prevent the new government in England from installing Puritans in positions of control in Maryland. They rescinded the Toleration Act in 1654, stripped Catholic colonists of voting rights, and denied them the right to worship. The once-persecuted Puritans had become persecutors themselves, at one point driving Calvert out of his own colony. Were it not for its success in growing tobacco, Maryland may well have disintegrated. In 1692, following the Glorious Revolution in England, officials banned Catholicism in Maryland. Only after the American Revolution would Marylanders again be guaranteed religious freedom.

NEW ENGLAND

Quite different English settlements emerged north of the Chesapeake Bay colonies. Unlike Maryland and Virginia, the “New” England colonies were intended to be self-governing religious utopias. The New England settlers were not servants as in the Chesapeake colonies; they were mostly middle-class family groups that could pay their way across the Atlantic. Most male settlers were small farmers, merchants, seamen, or fishermen. Although its soil was not as fertile as that of the Chesapeake region and its growing season was much shorter, New England was a healthier place to live. Because of its colder climate, settlers avoided the infectious diseases like malaria that ravaged the southern colonies.

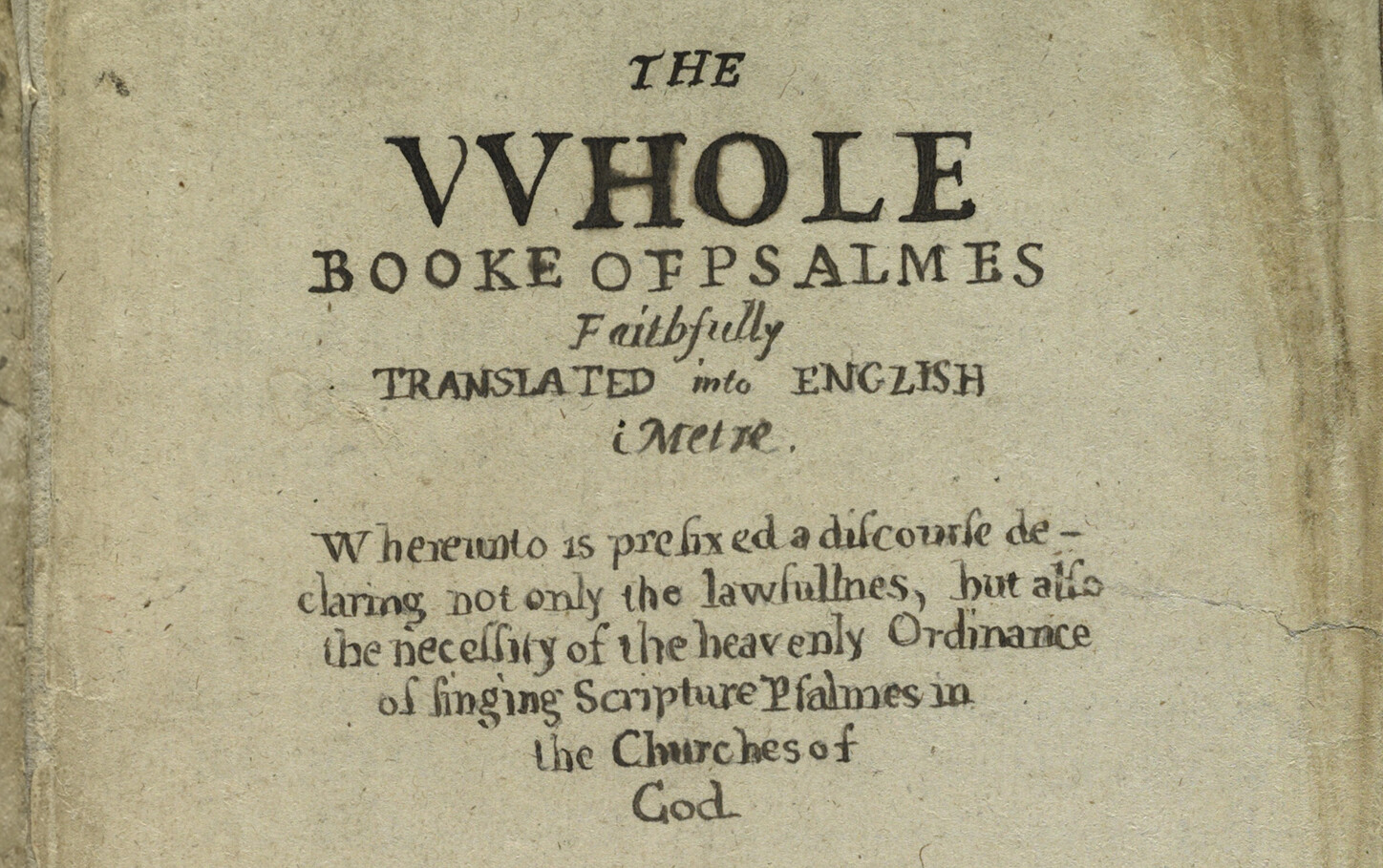

The Pilgrims and Puritans who arrived in Massachusetts were willing to sacrifice everything to create a model Christian society. These self-described “saints” remained subjects of the king, but they ruled themselves by following God’s biblical commandments. They also resolved to “purify” their church of all Catholic and Anglican rituals. Such holy colonies, they hoped, would provide a living example of righteousness for a wicked England to imitate.

During the seventeenth century, only 21,000 colonists arrived in New England, compared with the 120,000 who went to the Chesapeake Bay colonies. By 1700, however, New England’s thriving White population exceeded that of Maryland and Virginia.

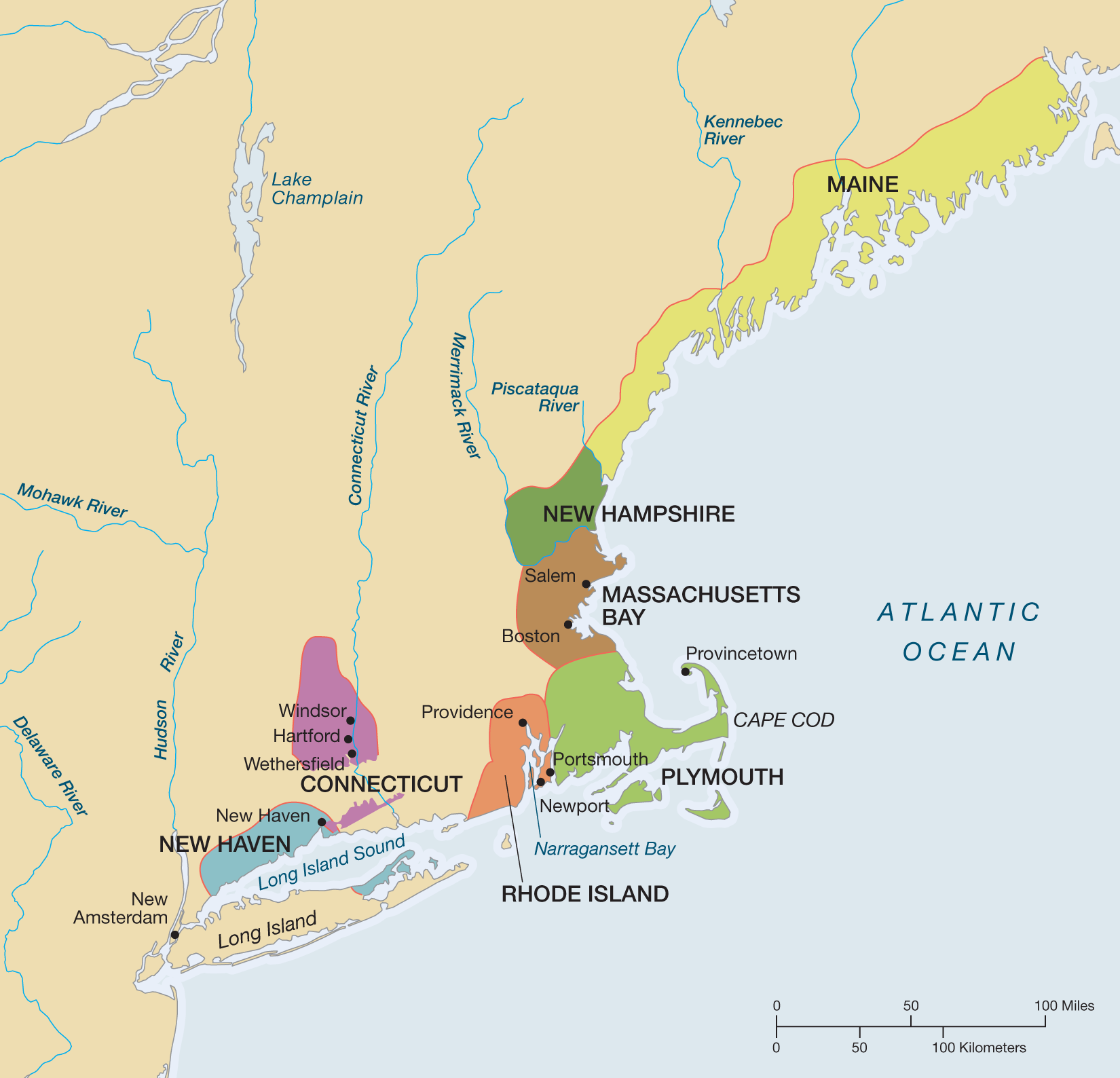

PLYMOUTH The first permanent English settlement in New England was established by the Plymouth Company, a group of seventy British investors. Eager to make money by exporting the colony’s abundant natural resources, the joint-stock company agreed to finance settlements in exchange for the furs, timber, and fish the colonists would ship back to England for sale. Among the first to accept the company’s offer were Puritan separatists who had been forced to leave England because they refused to worship in Anglican churches. The separatist “saints” demanded that each congregation govern itself rather than be ruled by a corrupt bureaucracy of bishops and archbishops. The Separatists, mostly simple farm folk, initially left England for Holland, where, over time, they worried that their children were embracing urban ways of life in Dutch Amsterdam. Such concerns led them to leave Europe and create a holy community in America.

In September 1620, a group of 102 women, men, and children crammed aboard the tiny Mayflower, a leaky, three-masted vessel barely 100 feet long, and headed across the Atlantic, bound for the Virginia colony, where they had obtained permission to settle. Many of them were what Puritan Separatists called “strangers” rather than saints because they were not part of the religious group. Each colonist received one share in the enterprise in exchange for working seven years in America as servants. It was hurricane season, however, and violent storms blew the ship off course to Cape Cod, southeast of what became Boston, Massachusetts. Having exhausted most of their food and water after spending sixty-six days crossing 2,812 miles, they had no choice but to settle there in “a hideous and desolate wilderness full of wild beasts and wild men.”

Once safely on land, William Bradford, who would become the colony’s second governor, noted that the pious settlers, whom he called Pilgrims, “fell upon their knees and blessed the God of Heaven who had brought them over the vast and furious ocean.” They called their hillside settlement Plymouth, after the English port city from which they had embarked.

Since the Mayflower colonists were outside the jurisdiction of any organized government, forty-one of them, all men, resolved to rule themselves. They signed the Mayflower Compact, a covenant (group contract) to form “a civil body politic” based on “just and civil laws” designed “for the general good.” The Mayflower Compact was not democracy in action, however. The saints granted only themselves the rights to vote and hold office. Their “inferiors”—the “strangers” and servants who also had traveled on the Mayflower—would have to wait for their civil rights.

The colonists settled in a deserted Indian village that had been devastated by smallpox. Those who had qualms about squatting on Indians lands rationalized them away. One Pilgrim soothed his guilt by explaining that the Indians were “not industrious.” They had neither “art, science, skill nor faculty to use either the land or the commodities of it.” The Pilgrims experienced a “starving time” as had the early Jamestown colonists. During their first winter, almost half the colonists died, including fourteen of the nineteen women and six children. Only the theft of Indian corn enabled the English colony to survive.

- Why did European settlers first populate the Plymouth colony?

- How were the settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony different from those of Plymouth?

- What was the origin of the Rhode Island colony?

Eventually, a local Indian named Squanto (Tisquantum) taught the colonists to grow corn, catch fish, gather nuts and berries, and negotiate with the Wampanoags. Still, when a shipload of colonists arrived in 1623, they “fell a-weeping” as they found the original Pilgrims in such a “low and poor condition.” By the 1630s, Governor Bradford was lamenting the failure of Plymouth to become the thriving holy community he and others had envisioned.

MASSACHUSETTS BAY The Plymouth colony’s population never rose above 7,000, and after ten years it was overshadowed by its much larger neighbor, the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Like Plymouth, the new colony was also intended to be a holy commonwealth for Puritans, but the Massachusetts Bay Puritans were different from the Pilgrims. They remained Anglicans—they wanted to purify the Church of England from within. They were called non-separating Congregationalists because their churches were governed by their independent congregations rather than by an Anglican bishop in England. The Puritans believed they were God’s “chosen people.” They limited church membership to “visible saints”—those who could demonstrate to the congregation that they had received the gift of God’s grace.

In 1629, King Charles I gave a royal charter to the Massachusetts Bay Company, a group of Calvinist Puritans making up a joint-stock company. They were led by John Winthrop, a lawyer with intense religious convictions and mounting debts. Winthrop wanted the colony to be a haven for Puritans and a model Christian community where faith would flourish. They would create “a City upon a Hill,” as he declared, borrowing the phrase from Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. “The eyes of all people are on us,” Winthrop said, so the Puritans must live up to their sacred destiny.

In 1630, Winthrop, his wife, three of his sons, and eight servants joined some 700 Puritan settlers on eleven ships loaded with cows, horses, supplies, and tons of beer, which remained safely drinkable much longer than did water. Unlike the first colonists in Virginia, most of the Puritans in Massachusetts arrived as family groups; they landed near the mouth of the Charles River, where they built a village and called it Boston, after the English town of that name. Winthrop was delighted to discover that the local Indians had been “swept away by the smallpox . . . so God hath hereby cleared our title to this place.” Disease knew no boundaries, however. Within eight months, some 200 Puritans had died of various illnesses, and many others had returned to England. Planting colonies was not for the faint-hearted. Anne Bradstreet, who became one of the first colonial poets, lamented the severe living conditions: “After I was convinced it was the way of God, I submitted to it.” What eventually allowed the Massachusetts Bay Colony to thrive was a flood of additional colonists who brought money, skills, and needed supplies.

John Winthrop had cleverly taken the royal charter for the colony with him to America, thereby transferring government authority from London to Massachusetts, where he and others hoped to govern their godly colony with little oversight by the monarchy. John Winthrop was determined to enforce religious devotion and ensure social stability. He and other Puritan leaders prized stability and hated the idea of democracy—the people ruling themselves. As the Reverend John Cotton explained, “If the people be governors, who shall be governed?” For his part, Winthrop claimed that a democracy was “the worst of all forms of government.” Puritan leaders never embraced religious toleration, political freedom, social equality, or cultural diversity. They believed that the role of government should be to enforce religious beliefs and ensure social stability. Ironically, the same Puritans who had fled persecution in England did not hesitate to persecute people of other religious views in New England. Catholics, Anglicans, Quakers, and Baptists had no rights; they were punished, imprisoned, banished, tortured, or executed.

Unlike “Old” England, New England had no powerful lords or bishops, kings or queens. The Massachusetts General Court, wherein power rested under the royal charter, consisted of all the shareholders, called freemen. At first, the freemen had no power except to choose “assistants,” who in turn elected the governor and deputy governor. In 1634, however, the freemen turned themselves into the General Court, with two or three deputies to represent each town. A final stage in the democratization of the government came in 1644, when the General Court organized itself like the Parliament. Henceforth, all decisions had to be ratified by a majority in each house.

Thus, over fourteen years, the joint-stock Massachusetts Bay Company evolved into the governing body of a holy commonwealth in which freemen exercised increasing power. Puritans had fled not only religious persecution but also political repression, and they ensured that their liberties in New England were spelled out and protected. Over time, membership in a Puritan church replaced the purchase of stock as the means of becoming a freeman in Massachusetts Bay.

RHODE ISLAND More by accident than design, the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the staging area for other New England colonies created by people dissatisfied with Puritan control. Young Roger Williams, who had arrived from England in 1631, was among the first to cause problems, precisely because he was the purest of Puritans—a Separatist. He criticized Puritans for not completely cutting their ties to the “whorish” Church of England. Where John Winthrop cherished strict governmental and clerical authority, Williams championed individual liberty and criticized the way colonists were mistreating Indians.

The combative Williams sought to be the holiest of the holy—at whatever cost. To that end, he posed a fundamental question: If one’s salvation depends solely upon God’s grace, why bother to have churches at all? Why not give individuals the right to worship God in their way? In Williams’s view, true Puritanism required complete separation of church and government and freedom from all coercion in matters of faith. “Forced worship,” he declared, “stinks in God’s nostrils.” According to Williams, governments should be impartial regarding religions.

Such radical views led the General Court to banish him to England. Before Williams could be deported, however, he escaped during a blizzard and found shelter among the Narragansett Indians. In 1636, he bought land from the Indians and established the town of Providence at the head of Narragansett Bay, the first permanent settlement in Rhode Island and the first in America to allow complete freedom of religion.

From the beginning, the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was the most democratic of the colonies, governed by the heads of households rather than by church members. Newcomers could be admitted to full citizenship by a majority vote, and all who fled religious persecution were welcomed. For their part, the Massachusetts Puritans came to view Rhode Island as a refuge for rogues. A Dutch visitor reported that Rhode Island was “the sewer of New England. All the cranks of New England retire there.”

Roger Williams was only one of several prominent Puritans who clashed with Governor John Winthrop’s stern, unyielding governance of the Bay Colony. Another, Anne Hutchinson, quarreled with Puritan leaders for different reasons. The strong-willed wife of a prominent merchant, Hutchinson raised thirteen children and hosted meetings in her Boston home to discuss sermons. Soon, however, the discussions turned into large gatherings (of both men and women) at which Hutchinson discussed religious matters. According to one participant, she “preaches better Gospel than any of your black coats [male ministers].” Blessed with extensive biblical knowledge and a quick wit, Hutchinson claimed to know which of her neighbors had gained salvation and which were damned, including ministers.

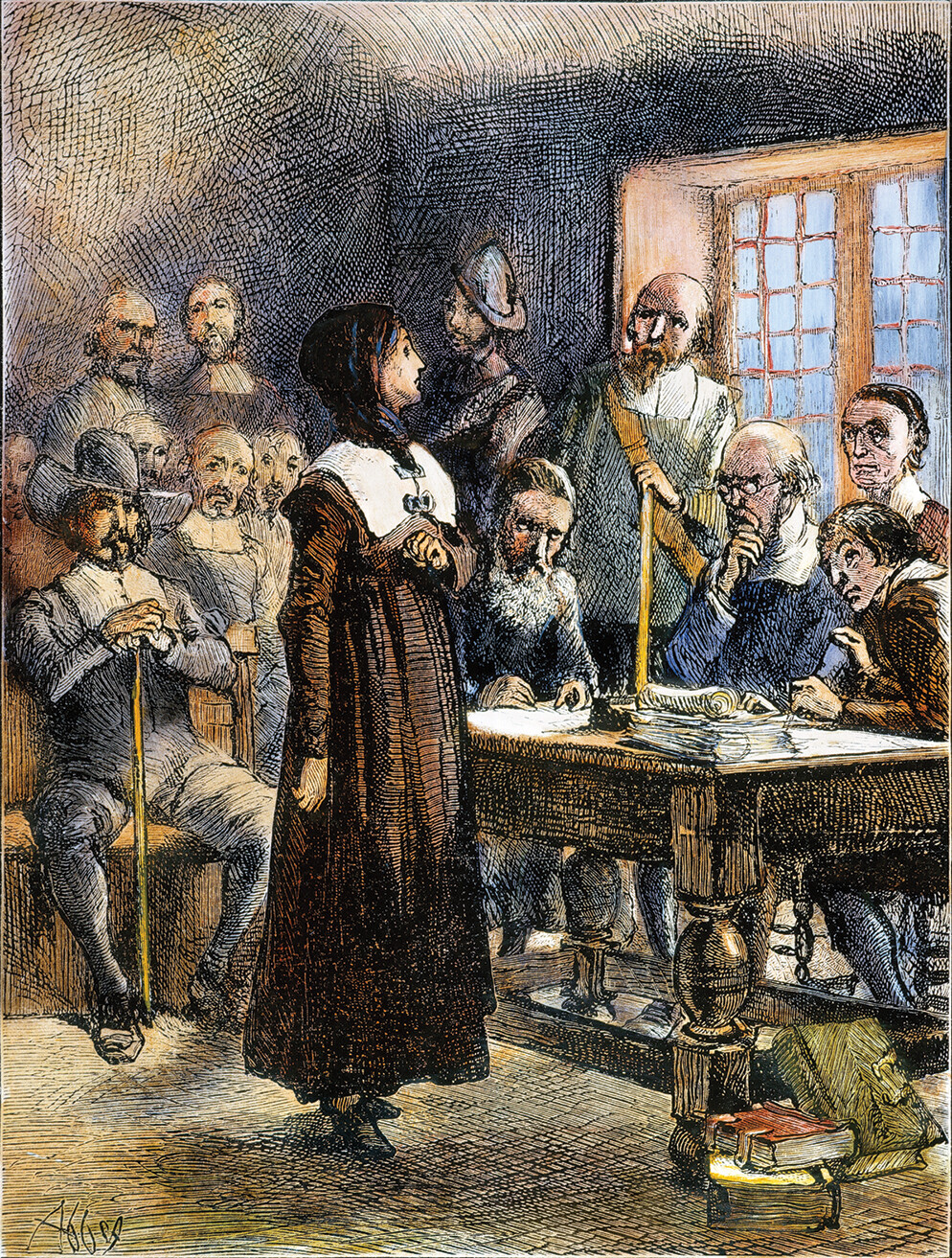

A pregnant Hutchinson was hauled before the all-male General Court in 1637 for trying to “undermine the Kingdom of Christ.” For two days she sparred on equal terms with the Puritan leaders, steadfastly refusing to acknowledge any wrongdoing. Hutchinson’s ability to cite chapter-and-verse biblical defenses of her actions led an exasperated Governor Winthrop to explode: “We are your judges, and not you ours. . . . We do not mean to discourse [debate] with those of your sex.” As the trial continued, the Court lured Hutchinson into convicting herself when she claimed to have received direct revelations from God. This was blasphemy in the eyes of Puritans, for if God were speaking directly to her, there was no need for ministers or churches.

In 1638, the General Court excommunicated Hutchinson from the church and banished her for having behaved like a “leper” not fit for “our society.” She initially settled with her family and followers on an island in Rhode Island’s Narragansett Bay. The hard journey took its toll, however. Hutchinson grew sick, and her fourteenth baby was stillborn.

Hutchinson’s spirits never recovered. After her husband’s death, in 1642, she moved near New Amsterdam (New York City), which was then under Dutch control. The following year, Indians massacred Hutchinson and six of her children. Her fate, wrote a spiteful John Winthrop, was “a special manifestation of divine justice.”

CONNECTICUT, NEW HAMPSHIRE, AND MAINE Connecticut had a more conventional beginning than did Rhode Island. In 1636, the Reverend Thomas Hooker led three congregations from Massachusetts Bay to the Connecticut Valley, where they organized the self-governing colony of Connecticut. Three years later, the Connecticut General Court adopted the Fundamental Orders, laws that provided for a “Christian Commonwealth” like that of Massachusetts, except that voting was not limited to church members.

In 1622, the king gave a vast tract of land that would encompass the states of New Hampshire and Maine to Sir Ferdinando Gorges and Captain John Mason. In 1629, the two divided their territory. Mason took the southern part, which he named the Province of New Hampshire, and Gorges opted for the northern region, which became the Province of Maine. During the early 1640s, Massachusetts took over New Hampshire and in the 1650s extended its authority to the scattered settlements in Maine. The land grab led to lawsuits, and in 1678 English judges decided against Massachusetts. In 1679, New Hampshire became a royal colony, but Massachusetts continued to control Maine. A new Massachusetts charter in 1691 finally incorporated Maine into Massachusetts.

THE CAROLINAS

Carolina, the southernmost mainland British American colony in the seventeenth century, began as two widely separated areas which, in 1712, officially became North and South Carolina. The northernmost part, long called Albemarle, had been settled in the 1650s by colonists who had drifted southward from Virginia. For a half century, Albemarle remained a remote scattering of farms along the shores of Albemarle Sound.

THE BARBADOS CONNECTION The eight prominent nobles, called lords proprietors, to whom the king had given Carolina neglected Albemarle and instead focused on more-promising sites to the south. They recruited established English planters from Barbados, the most easterly of the Caribbean “sugar islands.” Barbados was the oldest, most profitable, and most horrific colony in English America, a place notorious for its brutal treatment of enslaved workers, many of whom were literally worked to death.

To seventeenth-century Europeans, sugar was a new and much-treasured luxury item. The sugar trade fueled the wealth of European nations and enabled them to finance their colonies in the Americas. By the 1720s, half the ships traveling to and from New York City were carrying Caribbean sugar. In the 1640s, English planters transformed Barbados into an agricultural engine dotted by fields of sugarcane. Like the bamboo it resembles, sugarcane thrives in hot, humid climates. Barbadian sugar, then called “white gold,” generated more money for the British than the rest of their American colonies combined.

The British had developed an insatiable appetite for Asian tea and West Indian coffee, both of which they sweetened with Caribbean sugar. As one planter noted, sugar was no longer “a luxury; but has become by constant use, a necessary of life.”

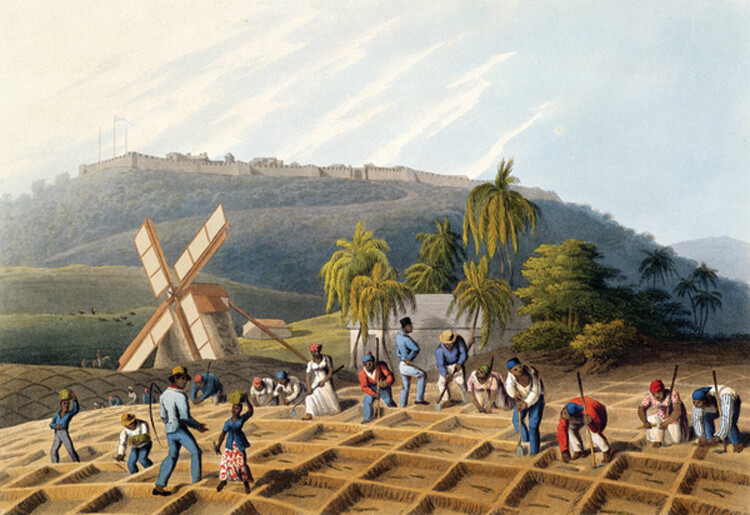

Sugar was hard to produce. Enslaved Africans used machetes to harvest the canes, then hauled them to wind-powered grinding mills where they were crushed to extract the sap. The sap was boiled, and the hot “juice”— liquid sugar—was poured into troughs to granulate before being shoveled into barrels, which were stored in a curing house to allow for the molasses to drain off. The resulting brown sugar, called muscovado, would be shipped to refiners to be prepared for sale. The molasses was distilled into rum, the most popular drink in the colonies. By the early seventeenth century, the British sugar colonies—Barbados, St. Kitts, Nevis, Antigua, and Jamaica—were sending tons of molasses and sugar to Europe and British America.

Barbados was dominated by a few wealthy planters who depended on enslaved Africans to do the work. An Englishman pointed out in 1666 that Barbados and the other “sugar colonies” thrived because of enslaved “Negroes” and “without constant supplies of them cannot subsist.” So many of the enslaved in Barbados died from overwork, poor nutrition, and disease that the sugar planters required a steady stream of Africans to replace them. Because all available land on the island was under cultivation, the sons and grandsons of the planter elite were forced to look elsewhere to find plantations of their own. Many seized the chance to settle Carolina and bring with them the Barbadian plantation system. In this sense, Carolina became “the colony of a colony,” an offspring of the sugar-and-slave culture in Barbados.

CHARLES TOWN The first 145 English colonists in South Carolina arrived in 1669 at Charles Town (later Charleston), on the west bank of the Ashley River. They brought three enslaved Africans with them. Over the next twenty years, half the colonists came from Barbados and other island colonies in the Caribbean, such as Nevis, St. Kitts, and Jamaica. Six of South Carolina’s royal governors between 1670 and 1730 were Barbadian English planters.

The Carolina coastal plain so impressed settlers with its flatness that they called it the low country. As one of them reported, “it is so level that it may be compared to a bowling alley.” Planters from the Caribbean brought to Carolina enormous numbers of enslaved Africans to clear land, plant crops, herd cattle, and slaughter pigs and chickens. Carolina, a Swiss immigrant said, “looks more like a negro country than like a country settled by white people.”

- How were the Carolina colonies created?

- What were the impediments to settling North Carolina?

- How did the lords proprietors settle South Carolina? What were the major items traded by settlers in South Carolina?

The government of Carolina grew out of a unique document, the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, drafted by one of the eight proprietors, Lord Anthony Ashley Cooper, with the help of his secretary John Locke. The constitution called for a royal governor, a council, and a Commons House of Assembly. In practice, however, what became South Carolina was dominated by a group of prominent Englishmen who were awarded large land grants. To generate an agricultural economy, the Carolina proprietors awarded land grants (“headrights”) to every male immigrant who could pay for passage across the Atlantic. The Fundamental Constitutions granted religious toleration, which gave Carolina a higher degree of religious freedom (extending to Jews and “heathens”) than in England or any other colony except Rhode Island.

In 1685, the Carolina colony received an unexpected surge of immigrants after French King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had guaranteed the civil rights of the Huguenots (French Protestants). Hundreds of Huguenots settled in Carolina to avoid religious persecution at the hands of the Catholic monarchy.

The early settlers in Carolina experienced morale-busting hardships. “I have been here for six months,” twenty-three-year-old Judith Manigault, a Huguenot refugee serving as a servant, wrote to her brother in Europe, reporting that she had been “working the ground like a slave,” and had “suffered all sorts of evils.” But “God surely gave us good grace to have been able to withstand all sorts of trials.” Her son Gabriel benefited from her perseverance; he would become one of the richest men in the province.

In 1712, the proprietors divided the Carolina colony into North and South, and seven years later, South Carolina became a royal colony. North Carolina remained under the proprietors’ rule until 1729, when it, too, became a royal colony.

The two Carolinas proved to be wise investments. Both colonies had vast forests of pine trees that provided lumber and other materials for shipbuilding. The sticky pine resin could be boiled to make tar, which was used to waterproof the seams of wooden ships, which is why North Carolinians came to be called Tar Heels.

Rice rather than sugar became the dominant crop in South Carolina because it was perfectly suited to the hot, humid growing conditions. Rice, like sugarcane and tobacco, is a labor-intensive crop, and plantation owners preferred enslaved Africans to work their fields rather than employing indentured servants. This was largely because West Africans had been growing rice for generations. A British traveler noted that rice in the low country could only be profitable through “the labor of slaves.”

By the start of the American Revolution in 1775, South Carolina would be the most profitable of the thirteen colonies, and some of its rice planters were among the wealthiest men in the world. It also hosted the most enslaved Blacks, over 100,000 of them compared with only 70,000 Whites. In 1737, the lieutenant governor warned, “Our negroes are very numerous and more dreadful to our safety than any Spanish invaders.”

THE MIDDLE COLONIES AND GEORGIA

The area between New England and the Chesapeake—Maryland and Virginia—included the “middle colonies” of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania, which were initially controlled by the Dutch. The Dutch Republic, a coalition of seven provinces also called the Netherlands or Holland, comprised 2 million people who gained their independence from Spanish control in 1581. By 1670, the mostly Protestant Dutch had the largest fleet of merchant ships in the world and controlled northern European trade. They had become one of the most diverse and tolerant societies in Europe—and England’s fiercest competitor in international commerce.

NEW NETHERLAND BECOMES NEW YORK The Dutch East India Company (organized in 1602) had hired English sea captain Henry Hudson to explore America in hopes of finding a northwest passage to the Indies. Sailing along the coast of North America in 1609, Hudson crossed Delaware Bay and then sailed ninety miles up the “wide and deep” river that eventually would be named for him. The Hudson River would become one of the most strategically important waterways in America. It was deep enough for oceangoing vessels to travel north into the interior, where the Dutch acquired thousands of beaver and otter pelts harvested by Indians. In exchange, the Indians received iron kettles, axes, knives, weapons, rum, cloth, and various trinkets.

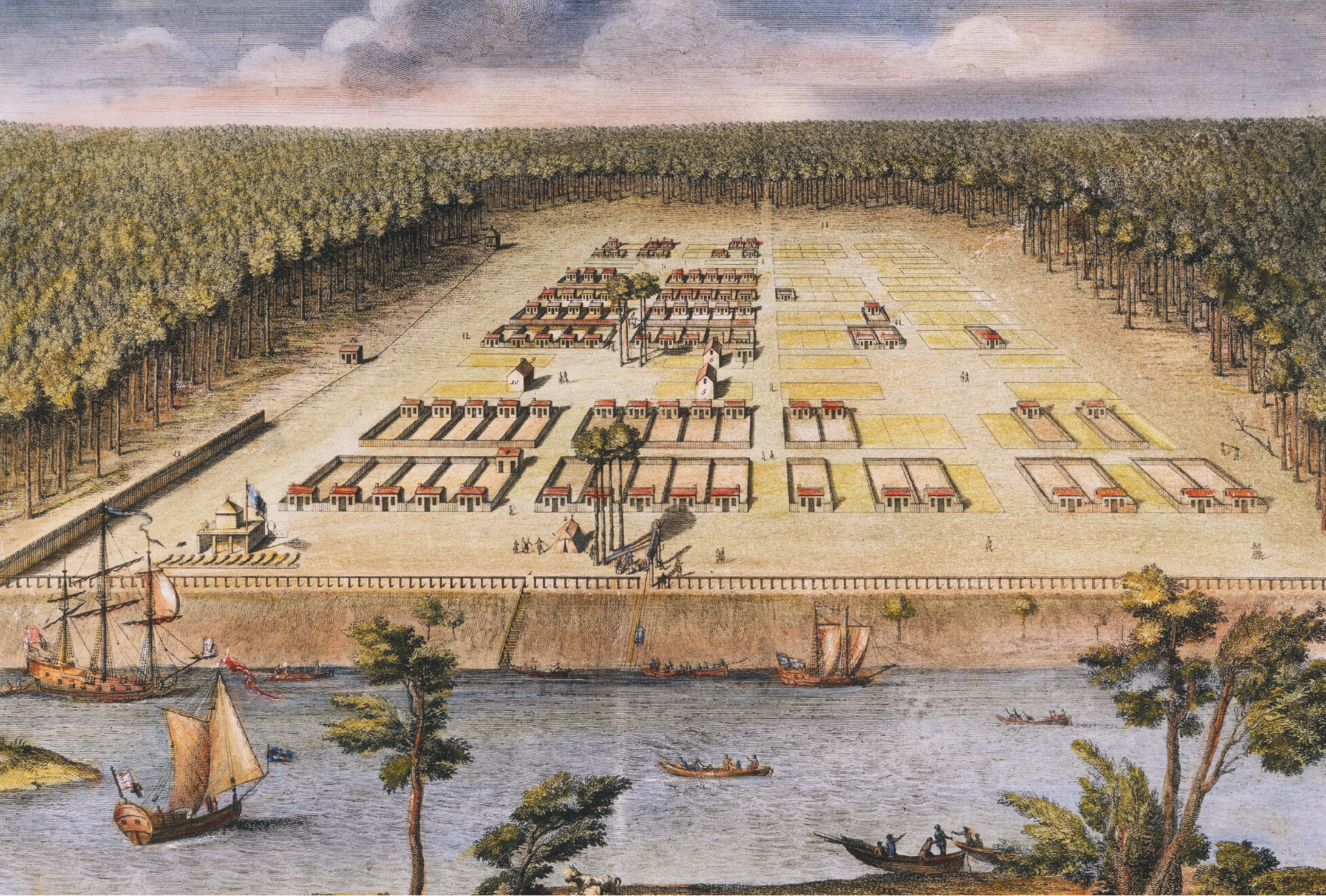

The New Netherland colony emerged as a profit-making enterprise owned by a corporation, the Dutch West India Company. “Everyone here is a trader,” explained one resident. Like the French, the Dutch were interested mainly in the fur trade, as the European demand for beaver hats created huge profits. In 1610, the Dutch established fur-trading posts on Manhattan Island and upriver at Fort Orange (later called Albany).

In 1626, the Dutch governor purchased Manhattan (an Indian word meaning “island of many hills”) from the Indians for 60 guilders, or about $1,000 in current value. The Dutch then built a fort and a fur-trading post at the lower end of the island. The village of New Amsterdam (eventually New York City), which grew up around the fort, became the capital of New Netherland. The Dutch West India Company controlled political life in New Netherland. It appointed the colony’s governor and advisory council and prohibited any form of elected legislature. All commerce with the Netherlands had to be carried in the company’s ships, and the company controlled the fur trade with the Indians.

In 1629, the Dutch West India Company, needing more settlers outside Manhattan to protect the colony from Indian attacks, awarded wealthy individuals large estates called patroonships. In exchange, the patroons had to host at least fifty settlers. Like a feudal lord, the patroon (from the Latin word for father) provided cattle, tools, and buildings. His tenants paid him rent, used his gristmill for grinding flour, and submitted to a court he established.

Unlike most other European nations with colonies in the Americas, the Dutch embraced ethnic and religious diversity; their passion for profits outweighed their social prejudices. Barely half the residents in the Dutch colony were Dutch. New Netherland welcomed exiles from across Europe: Spanish and German Jews, French Protestants (Huguenots), English Puritans, and Catholics. There were even Muslims in New Amsterdam, where in the 1640s the 500 residents communicated in eighteen different languages.

The Dutch did not show the same tolerance for Native Americans, however. Soldiers regularly massacred neighboring Indians. At Pound Ridge, Anglo-Dutch soldiers surrounded an Indian village, set it ablaze, and killed all who tried to escape. Such horrific acts led the Indians to respond in kind.

Dutch tolerance had other limitations. In September 1654, a French ship arrived in New Amsterdam harbor carrying twenty-three Sephardim, Jews of Spanish-Portuguese descent. They had come seeking refuge from Portuguese-controlled Brazil and were the first Jewish settlers to arrive in North America. The colonial governor, Peter Stuyvesant, refused to accept them. He dismissed Jews as a “deceitful race” and “hateful enemies.” Dutch officials overruled him, however, pointing out that it would be “unreasonable and unfair” to refuse to provide the Jews a haven. They wanted to “allow everyone to have his own belief, as long as he behaves quietly and legally, gives no offense to his neighbor, and does not oppose the government.”

Not until the late seventeenth century could Jews worship in public, however. Such restrictions help explain why the American Jewish community grew so slowly. In 1773, more than 100 years after the first refugees arrived, Jews represented only one-tenth of 1 percent of the entire colonial population. Not until the nineteenth century would the Jewish community in the United States witness dramatic growth.

In 1626, the Dutch West India Company began importing enslaved Africans to meet its labor shortage. By the 1650s, New Amsterdam had one of the largest slave markets in America.

The extraordinary success of the Dutch economy also proved to be its downfall, however. Like imperial Spain, the Dutch Empire expanded too rapidly. The Dutch dominated the European trade with China, India, Africa, Brazil, and the Caribbean, but they could not control their far-flung possessions, and it did not take long for European rivals to exploit the sprawling empire’s weak points. The Dutch in North American especially distrusted the English. A New Netherlander complained that the English were a people “of so proud a nature that they thought everything belonged to them.”

In London, King Charles II decided to seize New Netherland. In 1664, the residents of New Amsterdam balked when Governor Stuyvesant called on them to defend the colony against an English invasion fleet. After the English surrounded New Amsterdam and threatened the “absolute ruin and destruction of fifteen hundred innocent souls,” Stuyvesant surrendered the colony without firing a shot.

The Dutch negotiated an unusual surrender agreement that allowed New Netherlanders to retain their property, churches, language, and local officials. The English renamed the harbor city of New Amsterdam as New York, in honor of James Stuart, the Duke of York and the king’s brother, who had led the successful invasion. As a reward, the king granted his sibling the entire Dutch region of New Netherland and named it for him: New York.

NEW JERSEY Shortly after the conquest of New Netherland, James Stuart, the Duke of York, granted the lands between the Hudson and Delaware Rivers to Sir George Carteret and Lord John Berkeley (brother of Virginia’s governor) and named the territory for Carteret’s native Jersey, an island in the English Channel. In 1676, by mutual agreement, New Jersey was divided into East and West Jersey, with Carteret taking the east, Berkeley the west.

New settlements arose in East Jersey. Disaffected Puritans from the New Haven colony in Connecticut founded Newark, Carteret’s brother brought a group to found Elizabethtown, and a group of Scots founded Perth Amboy. In the west, a scattering of Swedes, Finns, and Dutch remained, but they were soon overwhelmed by swarms of English and Welsh Quakers, as well as German and Scots-Irish settlers.

The Scots-Irish were mostly Presbyterian Scots recruited by the English government during the first half of the seventeenth century to migrate to Ulster, in northern Ireland, and thereby dilute the appeal of Catholicism and anti-English rebellions. Many of them struggled to make a living in Ulster. One of them highlighted the benefits of life in America: “The price of land [here] is so low . . . forty or fifty pounds will purchase as much ground [in America] as one thousand pounds [would buy in Ireland]. In 1702, East and West Jersey were united as the single royal colony of New Jersey.

- Why was New Jersey divided in half?

- Why did Quakers choose to settle in Pennsylvania?

- How did the relations between European settlers and Indians in Pennsylvania differ from such relations in the other colonies?

PENNSYLVANIA The Society of Friends, known as Quakers because they were supposed to “tremble at the word of the Lord,” became the most influential of several new religious groups that emerged from the English Civil War. Founded in England in 1647, the Quakers rebelled against all forms of political and religious authority, including salaried ministers, military service, and paying taxes. They insisted that everyone, not just a select few, could experience a personal revelation from God, what they called the “Inner Light.” Quakers discarded all formal religious rituals and embraced a fierce pacifism. Some Quakers went barefoot, others wore rags, and a few went naked to demonstrate their “primitive” commitment to Christ. Quakers demanded complete religious freedom for everyone and promoted equality of the sexes, including the full participation of women in religious affairs.

Quakers suffered intense persecution. New England Puritans banned them, slit their noses, lopped off their ears, and executed them. Often, the Quakers seemed to invite such abuse. In 1663, for example, Lydia Wardell, a Massachusetts Quaker, grew so upset with the law requiring everyone to attend religious services that she arrived at the church naked to dramatize her protest. Puritan authorities ordered her “to be severely whipped.”

The settling of English Quakers in West Jersey encouraged other Friends to migrate, especially to the Delaware River side of the colony, where William Penn founded a Quaker commonwealth, the colony of Pennsylvania. Penn, the son of the celebrated admiral Sir William Penn, was one of the most improbable of colonial leaders. While a student at Oxford University, he was expelled for criticizing the requirement that students attend daily chapel services in the Anglican church. His furious father banished his son from their home. The younger Penn lived in France for two years, then studied law before moving to Ireland to manage the family’s estates. While he was there, officials arrested him in 1666 for attending a Quaker meeting. Much to the chagrin of his parents, Penn became a Quaker and was arrested several more times for his religious convictions.

Upon his father’s death, William Penn inherited a substantial fortune, including a sprawling tract of land in America. The king insisted that the land be named in honor of Penn’s father—Pennsylvania (literally, Penn’s Woods). Unlike John Winthrop in Massachusetts, Penn encouraged people of all faiths, nations, and social standing to live together in harmony. By the end of 1681, thousands of immigrants embracing different religions had settled in his new colony, and a town was emerging at the junction of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers. Penn called it Philadelphia (meaning City of Brotherly Love).

The relations between the Native Americans and the Pennsylvania Quakers were unusually good because of the Quakers’ friendliness and Penn’s policy of purchasing land titles from Native Americans. Penn told the Delaware Nation that he wanted to enjoy the land “with your love and consent, that way we may always live together as neighbors and friends.” For some fifty years, the Pennsylvania colonists and Native Americans lived in peace.

The colony’s government resembled that of other proprietary colonies except that the freemen (owners of at least fifty acres) elected the council members as well as the assembly. The governor had no veto, although Penn, as proprietor, did. Penn hoped to show that a colonial government could abide by Quaker principles. It could maintain peace and order, while demonstrating that religion could flourish without government support and with absolute freedom of conscience.

Over time, however, the Quakers struggled to forge a harmonious colony. In Pennsylvania’s first ten years, it went through six governors. A disappointed Penn, who only visited his colony twice, wrote from London: “Pray [please] stop those scurvy quarrels that break out to the disgrace of the province.” Even more ironic was that as Penn’s colony began to flourish, he slid into poverty, eventually landing in debtor’s prison.

DELAWARE In 1682, the Duke of York also granted William Penn the area known as Delaware. It was another part of the former Dutch territory (which had been New Sweden before being acquired by the Dutch in 1655). Delaware took its name from the Delaware River, which had been named to honor Thomas West, Baron De La Warr (1577–1618), Virginia’s first colonial governor. Delaware became part of Pennsylvania, but after 1704 it was granted the right to choose its legislative assembly. From then until the American Revolution, Delaware had a separate assembly but shared Pennsylvania’s governor.

GEORGIA The last English colony to be founded, Georgia, emerged a half century after Pennsylvania. During the seventeenth century, settlers pushed southward into the borderlands between Carolina and Spanish Florida. They brought enslaved Africans and a desire to win the Indian trade from the Spanish. Each side used guns, gifts, and rum to court the Native Americans, and they, in turn, played the English against the Spanish.

In 1732, King George II gave the land between the Savannah and Altamaha Rivers to twenty-one trustees appointed to govern the Province of Georgia, named in honor of the king. Georgia provided a military buffer against Spanish Florida. It also served as a social experiment by bringing together settlers from different countries and religions, many of them refugees, debtors, or members of the “worthy poor.” General James E. Oglethorpe, a prominent member of Parliament, was appointed to head the colony.

In 1733, about 120 colonists established Savannah on the Atlantic coast near the Savannah River. Carefully laid out by Oglethorpe, the town, with its geometric pattern of crisscrossing roads graced by numerous parks, remains a splendid example of city planning. Protestant refugees from Austria began to arrive in 1734, followed by Germans and German-speaking Moravians and Swiss, who for a time made the colony more German than English. The addition of Welsh, Highland Scots, Sephardic Jews, and others gave the early colony a diverse ethnic character like that of Charleston, South Carolina.

As a buffer against Spanish Florida, the colony succeeded, but as a social experiment creating a “common man’s utopia,” Georgia failed. Initially, landholdings were limited to 500 acres to promote economic equality. Rum was banned, and the importation of the enslaved was forbidden. The idealistic rules soon collapsed, however, as the colony struggled to become self-sufficient. The regulations against rum and slavery were widely disregarded and finally abandoned. By 1759, all restrictions on landholding had been removed.

In 1752, Georgia became a royal colony. It developed slowly but boomed in population and wealth after 1763, when it came to resemble the plantation society in South Carolina. Georgians exported rice, lumber, beef, and pork, and they carried on a lively trade with the islands in the West Indies. Almost unintentionally, the colony had become an economic success and a slave-centered society.

Glossary

- Powhatan Confederacy

- An alliance of several powerful Algonquian societies under the leadership of Chief Powhatan, organized into thirty chiefdoms along much of the Atlantic coast in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

- tobacco

- A “cash crop” grown in the Caribbean as well as the Virginia and Maryland colonies, made increasingly profitable by the rapidly growing popularity of smoking in Europe after the voyages of Columbus.

- headright

- A land-grant policy that promised fifty acres to any colonist who could afford passage to Virginia and fifty more for each accompanying servant. The headright policy was eventually expanded to include any colonists—and was also adopted in other colonies.

- Mayflower Compact (1620)

- A formal agreement signed by the Separatist colonists aboard the Mayflower to abide by laws made by leaders of their choosing.

- Massachusetts Bay Colony

- English colony founded by Puritans in 1630 as a haven for persecuted Congregationalists.

- North and South Carolina

- English proprietary colonies, originally formed as the Carolina colonies, officially separated into the colonies of North and South Carolina in 1712, whose semitropical climate made them profitable centers of rice, timber, and tar production.

- New Netherland

- Dutch colony conquered by the English in 1667, out of which four new colonies were created—New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.