![]() Jim Crow Segregation Laws at the End of the Nineteenth Century

Jim Crow Segregation Laws at the End of the Nineteenth Century

How and why did White southerners adopt “Jim Crow” segregation laws and take away African Americans’ right to vote at the end of the nineteenth century?

RACE RELATIONS DURING THE 1890S

The plight of southern farmers in the 1880s and 1890s affected race relations—for the worse. During the 1890s, White farmers and politicians demanded that Blacks be stripped of their voting rights and other civil rights. What northern observers called “Negrophobia” swept across the South and much of the nation.

In part, the resurgent wave of racism represented a revival of the idea that the Anglo-Saxon “race” of Whites, who originated in Germany and spread across western Europe and Great Britain, was intellectually and genetically superior to Blacks. Another reason was that many Whites had come to resent any signs of African American financial success and political influence. An Alabama newspaper editor reported, “Our blood boils when the educated Negro asserts himself politically.”

DISENFRANCHISING AFRICAN AMERICANS By the 1890s, many African Americans born and educated since the Civil War were determined to gain complete equality in terms of civil rights. They were more assertive and less patient than their parents. “We are not the Negro from whom the chains of slavery fell a quarter century ago, most assuredly not,” a Black editor announced. A growing number of young southern Whites, however, were equally determined to keep all “Negroes in their place.”

Mississippi took the lead in stripping Blacks of voting rights. The so-called Mississippi Plan (1890), a series of amendments to the state constitution, set the pattern of disenfranchisement that nine more southern states would follow. First, the Mississippi Plan of 1890 instituted a residence requirement for voting—two years in the state, one year in a local election district—aimed at African American tenant farmers who were in the habit of moving each year in search of better economic opportunities. Second, Mississippi disqualified Blacks from voting if they had committed certain crimes. Third, in order to vote, people had to have paid all taxes on time, including a so-called poll tax specifically for voting—a restriction that hurt both poor Blacks and poor Whites. Finally, all voters had to be able to read or at least “understand” the U.S. Constitution. White registrars decided who satisfied this requirement, and they frequently discriminated against Blacks.

Other states seeking to restrict Black voting had variations on the Mississippi Plan. In 1898, Louisiana inserted into its state constitution the “grandfather clause,” which allowed illiterate Whites to vote if their fathers or grandfathers had been eligible to vote on January 1, 1867, when African Americans were still disenfranchised. By 1910, Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, Alabama, and Oklahoma had incorporated the grandfather clause. Finally, every southern state created Democratic party primaries to select candidates, and most of these primaries excluded African American voters. When such “legal” means were not enough to ensure political dominance, White candidates turned to fraud and violence. Benjamin Tillman, the White supremacist who served as South Carolina’s governor from 1890 to 1894, claimed that his state’s problems were caused by “ignorant lazy negroes.” African Americans, Tillman argued, “must remain subordinate or be exterminated.”

Such openly racist views gained Tillman the support of most poor Whites. To ensure his election as governor, however, he and his followers sought to eliminate the Black vote. “We have done our level best [to prevent Black people from voting],” he bragged. “We stuffed ballot boxes. We shot them. We are not ashamed of it.”

The efforts of Tillman and other White supremacists to suppress the Black vote succeeded. In 1896, Louisiana had 130,000 registered Black voters; by 1900, it had only 5,320. In Alabama in 1900, the census data indicated that 121,159 Black men were literate; only 3,742, however, were registered to vote. By that year, Black voting across the South had declined by 62 percent, the White vote by 26 percent.

THE SPREAD OF SEGREGATION While southern Blacks were being shoved out of the political arena, they were also being segregated socially. The symbolic first target of such racial segregation was the railroad passenger car. In 1885, novelist George Washington Cable noted that in South Carolina, Black people “ride in first-class [rail] cars as a right” and “their presence excites no comment.” Likewise, in New Orleans a visitor was surprised to find that “white and colored people mingled freely.” From 1875 to 1883, in fact, any local or state law requiring racial segregation violated the federal Civil Rights Act.

In 1883, however, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the Civil Rights Act of 1875 was unconstitutional. The Court declared that neither the Thirteenth nor the Fourteenth Amendment gave Congress the authority to pass laws dealing with racial discrimination by private citizens or businesses. The judges explained that individuals and organizations could engage in acts of racial discrimination because the Fourteenth Amendment specified only that “no State” could deny citizens equal protection of the law.

The Court’s interpretation in what came to be called the Civil Rights Cases (1883) left as an open question the validity of city and state laws requiring racially segregated public facilities under the principle of “separate but equal,” a slogan referring to the argument that racial segregation laws were legal as long as the segregated facilities were equal in quality.

PLESSY V. FERGUSON (1896) In the 1880s, Florida, Tennessee, Texas, and Mississippi required railroad passengers to ride in racially segregated cars. When Louisiana followed suit in 1890 with a similar law, Blacks challenged it in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The case originated in New Orleans when Homer Plessy, an octoroon (a person with one-eighth African ancestry), refused to leave a Whites-only railroad car and was convicted of violating the law.

In 1896, the Supreme Court ruled that states could create laws segregating public places such as schools, hotels, and restaurants. Justice John Marshall Harlan, a Kentuckian who had once owned enslaved people, was the only justice to dissent. He stressed that the Constitution is “color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens. In respect of civil rights, all citizens are equal before the law.” Harlan feared that the Court’s ruling would plant the “seeds of race hate” under “the sanction of law.”

That is precisely what happened. The Plessy ruling endorsed racially “separate but equal” facilities in virtually every area of southern life. In 1900, the editor of the Richmond Times insisted that racial segregation “be applied in every relation of Southern life. God Almighty drew the color line, and it cannot be obliterated. The negro must stay on his side of the line, and the White man must stay on his side, and the sooner both races recognize this fact and accept it, the better it will be for both.

JIM CROW SEGREGATION The new regulations requiring racial segregation came to be called Jim Crow laws. The name derived from “Jump Jim Crow,” an old song-and-dance caricature of African Americans performed by White actor Thomas D. Rice in blackface makeup. Thereafter, the term Jim Crow became a satirical expression meaning “Negro.” Signs reading “Whites Only” or “Colored Only” above restrooms and water fountains emerged as hallmarks of the Jim Crow system of racial segregation. Old racist customs were revived. If Whites walked along a sidewalk, approaching Blacks were expected to step aside and let them pass. There were even racially separate funeral homes, cemeteries, and churches.

Widespread violence accompanied the creation of Jim Crow segregation laws. From 1890 to 1899, the United States averaged 188 lynchings per year, 82 percent of which occurred in the South. Lynchings usually involved a Black man (or men) accused of a crime, often rape. White mobs would seize, torture, and kill the accused, always in ghastly ways.

Racial lynchings became so common that Whites viewed them as forms of outdoor entertainment. Large crowds would watch the grisly event amid a carnival-like atmosphere. Photographs of gruesome lynchings surrounded by laughing and smiling Whites were reproduced on postcards mailed across the nation. Mississippi governor James Vardaman declared that “if it is necessary that every Negro in the state will be lynched, it will be done to maintain white supremacy.”

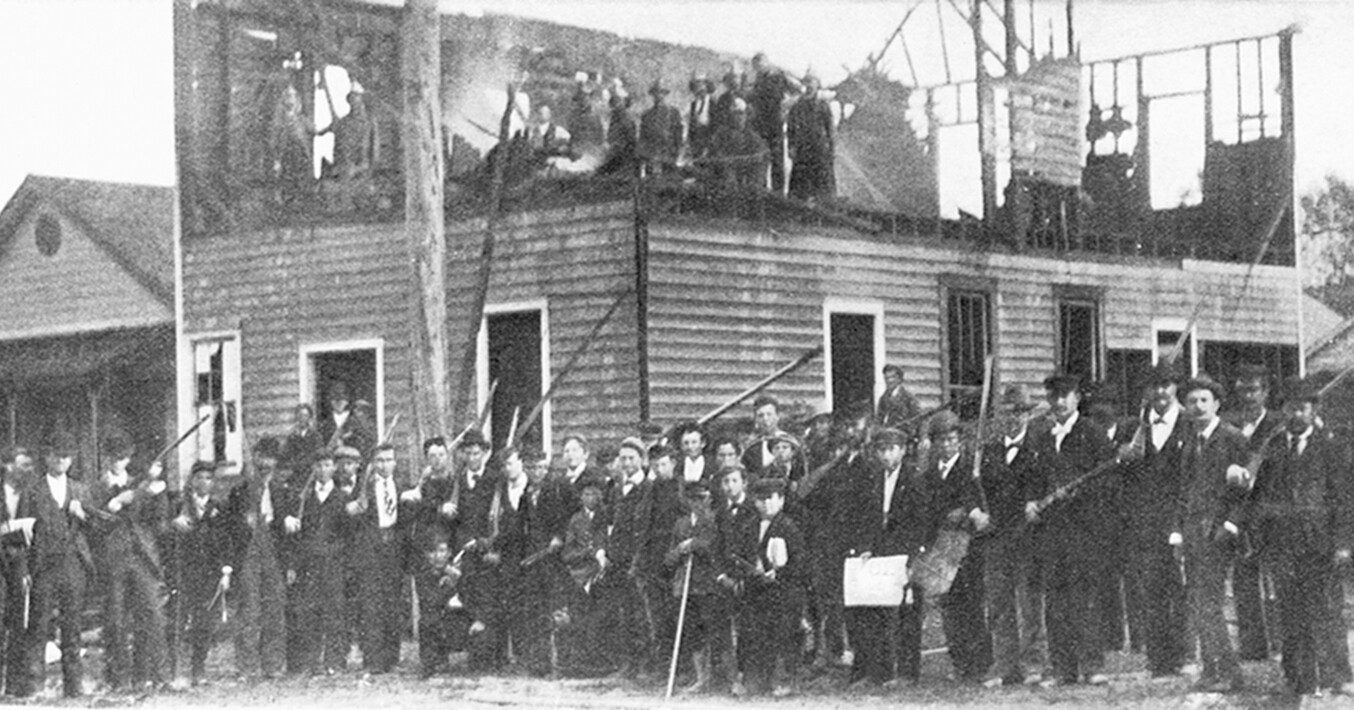

THE WILMINGTON INSURRECTION (1898) In the late 1890s, a violent wave of White supremacy spread across the South. In North Carolina’s largest city, the prosperous coastal port of Wilmington, Whites toppled the multiracial government in 1898.

In 1894 and 1896, Black voters, a majority in the city, had elected African Americans and White Republicans to various municipal offices. This infuriated the White supremacist elite, all of whom were Democrats. “We will never surrender to a ragged rabble of Negroes led by a handful of white cowards,” warned Alfred “Colonel” Waddell, a former congressman and Confederate officer.

On the day before elections in 1898, Waddell urged a mob of 1,500 armed ex-Confederates, militiamen, and prominent Democrats to “do your duty” as White men: “This city, county and state shall be rid of Negro domination, once and forever. Go to the polls tomorrow and if you find the negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls. And if he refuses, kill him! Shoot him down in his tracks.”

The crowd did as ordered. Whites rampaged through the polling places, forcing Blacks out at gunpoint and stuffing ballot boxes to ensure that White supremacist candidates won. The rioters, armed with rifles, pistols, and even a machine gun, destroyed the offices of the Daily Record, the Black-owned newspaper, and then moved into African American neighborhoods, where they killed sixty, wounded dozens, and destroyed homes and businesses. An out-of-town reporter marveled at the audacity of the White assault on the city government: “What they did was done in broad daylight.”

The mob stormed city hall, announced that “negro rule” was over, named Waddell mayor, and forced African American officials and their White Republican allies to resign. They then pushed prominent Blacks onto northbound trains, warning them never to return.

More than 2,000 African Americans fled the state or were forced out at gunpoint. The self-declared White supremacist city government issued a “Declaration of White Independence” that stripped Blacks of their jobs and voting rights. Desperate Blacks appealed to the governor and to President William McKinley, but they received no help. No one was ever convicted of the crimes committed against the African American community.

The Wilmington Insurrection (1898) marked the first—and only—time that an elected municipal government had been forcibly overthrown in the United States. Mayor Waddell boasted that his racist followers had “set the pace for the whole South on the question of white supremacy.”

Waddell and others convinced the state legislature to amend the constitution to create a poll tax and literacy test designed to disenfranchise Black voters. “The chief object” of the proposed amendments, said a Democratic pamphlet, “is to eliminate the ignorant and irresponsible Negro vote.” Such techniques worked better than anyone predicted. In 1896, there were 125,000 African Americans registered to vote in North Carolina. By 1902, there were only 6,000. The state legislature went on to pass the state’s first Jim Crow laws, segregating train cars by race. Laws mandating separate public toilets, water fountains, theaters, and parks soon followed.

THE BLACK RESPONSE TO SEGREGATION African Americans responded to racial segregation in various ways. Some left the South in search of greater safety, equality, and opportunity. Most, however, stayed in their native region and suffered the brutal imposition of White supremacy. Survival required Blacks to wear a mask of deference and to behave in a “servile way” when shopping at White-owned stores. “Had to walk a quiet life,” Virginian James Plunkett explained. “The least little thing you would do, they [Whites] would kill ya.”

Yet accommodation to White supremacy and segregation did not mean surrender. African Americans constructed their own lively culture. Churches continued to provide an anchor for Black communities and were often the only public buildings Blacks could use for large gatherings, such as club meetings, political rallies, and social events. For men especially, churches offered leadership roles and political status; women often did everything else.

One irony of Jim Crow segregation was that it created new economic opportunities for African Americans. Black entrepreneurs provided essential services to the Black community—insurance, banking, barbering, funerals, hair salons. Blacks also formed their own social and fraternal clubs and organizations, all of which provided fellowship, mutual support, and opportunities for service.

Middle-class African American women organized a network of social clubs that served as engines of community service across the South and the nation. They cared for the aged, infirm, orphaned, and abandoned, provided homes for single mothers and nurseries for working mothers, and sponsored health clinics and classes in home economics.

In 1896, the women’s clubs created the National Association of Colored Women. The organization’s first president, Mary Church Terrell, told members that they had an obligation to serve the “lowly, the illiterate, and even the vicious to whom we are bound by the ties of race and sex, and put forth every effort to uplift and reclaim them.” An editorial in the Woman’s Era called for “timid men and ignorant men” to step aside and let the women show the way.

Others pursued legal recourse to improve their quality of life. Tennessean Callie Guy House launched a mass movement in the 1890s demanding pensions for formerly enslaved people. In 1897, she helped found the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association. Its proposals were modeled after the military pensions being paid to Union military veterans. House and others crisscrossed the southern states promoting pensions for Blacks as reparation for the sin of slavery. By 1900, some 300,000 people had joined the organization.

Federal officials, however, opposed the pension idea. At the same time, the U.S. Post Office and Pensions Bureau harassed House and other officers of the group, falsely accusing them of mail fraud. House was arrested, tried, and sentenced to ten months in a federal prison. No pensions were ever paid to any formerly enslaved person.

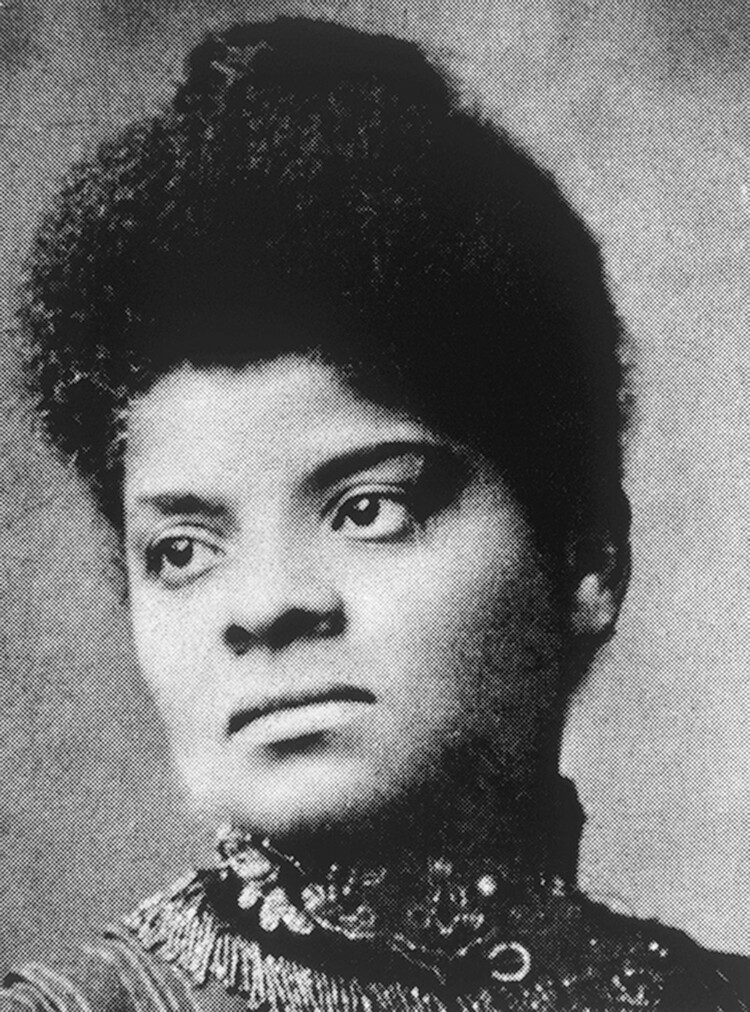

IDA B. WELLS One of the most outspoken African American activists was Ida B. Wells. Born into slavery in 1862 in Mississippi, she attended a school staffed by White missionaries. She moved to Memphis in 1880, where she taught in segregated schools and gained entrance to the African American middle class.

In 1883, Wells bought a first-class railroad ticket only to be forcibly removed from the car because she was Black. She did not go easily, biting and scratching the conductor before being removed. Wells then became the first African American to file a lawsuit challenging such discrimination. The circuit court decided in her favor and fined the railroad, but the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the ruling. Wells thereafter discovered “[my] first and [it] might be said, my only love”—journalism—which she used to fight for justice. She became the fearless editor of Memphis Free Speech, a newspaper that focused on African American issues.

In 1892, after three of her friends were lynched, Wells launched a crusade against lynching. “The more the Afro-American yields and cringes and begs,” Wells argued, “the more he is insulted, outraged, and lynched.” She described Memphis as a White-governed “town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood.”

Angry Whites responded by destroying her office and threatening to lynch her. Wells responded by purchasing a pistol, for she “felt one had better die fighting against injustice than to die like a dog or a rat in a trap.” Later, having decided that Memphis would “neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts,” Wells moved briefly to New York, and then settled in Chicago, where she continued to criticize Jim Crow laws and fought for the restoration of Black voting rights. “Somebody must show that the Afro-American race is more sinned against than sinning,” she explained, “and it seems to have fallen upon me to do so.”

Wells helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 and worked for women’s suffrage. In promoting racial equality, she often found herself in direct opposition to Booker T. Washington, the most influential African American leader in the nation.

BOOKER T. WASHINGTON Booker T. Washington was born a slave in Virginia in 1856, the son of a Black mother and a White father. At sixteen he enrolled at Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, one of several colleges created during Reconstruction specifically for newly emancipated African Americans. There he met the school’s founder, Samuel Chapman Armstrong, who was a former Union general who preached moderation and urged the students to “be thrifty and industrious,” “command the respect of your neighbors by a good record and a good character,” “make the best of your difficulties,” and “live down prejudice.” Washington listened and learned.

Nine years later, Armstrong received a request from a group in northern Alabama who were starting a Black college called Tuskegee Institute. They needed a president of the new school. Armstrong urged them to hire Washington. Although only twenty-five, he was, according to Armstrong, “a very capable mulatto, clear headed, modest, sensible, polite, and a thorough teacher and superior man.”

Young Washington got the job and quickly went to work. The first students had to help construct the institute’s first buildings by making the bricks themselves. As the years passed, Tuskegee Institute became celebrated as a college dedicated to discipline and vocational training.

Washington became a skilled fund-raiser, gathering substantial gifts from wealthy Whites, most of them northerners. The complicated racial dynamics of the late nineteenth century required him to walk a tightrope between candor and diplomacy, and he learned to mask his militancy to maintain the support of Whites. As the years passed, the pragmatic Washington became a source of inspiration and hope to millions of Blacks.

Washington’s recurring message to Black students focused on the importance of gaining “practical knowledge.” In part to please his White donors, he argued that African Americans should not focus on fighting racial segregation; they should pursue self-improvement rather than social change. Washington told them to begin “at the bottom” as well-educated, hardworking farmers, not as social activists.

In a famous speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895, Washington urged the African American community not to migrate to northern states or to other nations but to “cast down your [water] bucket where you are—cast it down in making friends . . . of the people of all races by whom we are surrounded. Cast it down in agriculture, [in] mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions.” Fighting for “social equality” and directly challenging White rule would be “the extremest folly,” and any effort at “agitation” would, he warned, backfire. African Americans first needed to become self-sufficient economically. Civil rights would have to wait.

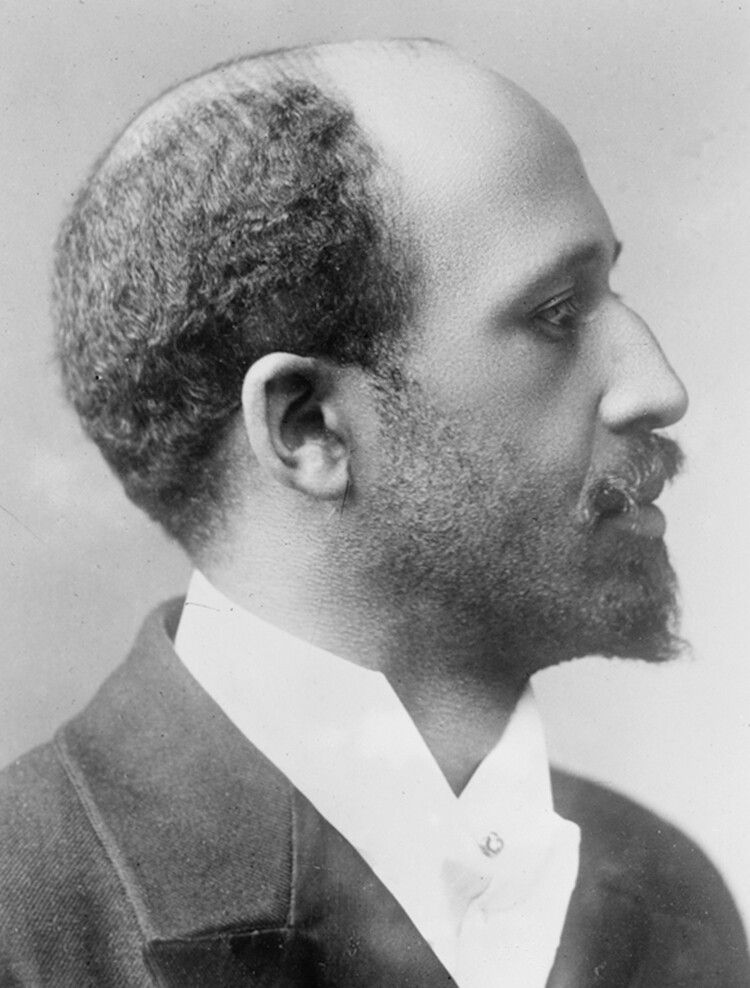

W. E. B. DU BOIS At the start of the twentieth century, some younger Black leaders began to criticize Washington for sacrificing civil and political rights in his crusade for vocational education. W. E. B. Du Bois led this criticism.

A native of Massachusetts, Du Bois graduated from Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Later he became the first African American to earn a doctoral degree from Harvard (in history and sociology). In addition to promoting civil rights, he left a distinguished record as a scholar, authoring more than twenty books.

In his most famous work, The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois highlighted the “double consciousness” felt by African Americans: “One ever feels his two-ness—an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Du Bois spent his career exploring this double consciousness and how it inevitably hindered Black progress. A young White visitor to Mississippi in 1910 noticed that nearly every Black person he met had “two distinct social selves, the one he reveals to his own people, the other he assumes among the whites.”

Trim and dapper, Du Bois had a flamboyant personality and a combative spirit. Not long after he began teaching at Atlanta University in 1897, he criticized Booker T. Washington’s conservative strategy for improving the quality of life for African Americans. Du Bois called Washington’s 1895 speech “the Atlanta Compromise” and the name stuck. Washington, he charged, was a coward so determined to please powerful Whites that he “accepted the alleged inferiority of the Negro” so Blacks could “concentrate all their energies on industrial education, the accumulation of wealth, and the conciliation of the South.”

Du Bois stressed that the priorities should be reversed—that African American leaders should adopt a strategy of “ceaseless agitation” directed at ensuring the right to vote and winning civil equality. The education of Blacks, Du Bois maintained, should not be merely vocational but should focus on developing bold leaders willing to challenge segregation and discrimination. He demanded that disenfranchisement and legalized segregation cease immediately and that the laws of the land be enforced.

For his part, Washington stressed that Du Bois, a new Englander, never understood the brutal dynamics of southern racism. A more militant strategy in the South would only have gotten more Blacks lynched. Nor did Du Bois or other critics know that Washington secretly financed legal efforts to oppose Jim Crow laws. Such “quiet efforts,” he noted, were more successful and realistic than the “brass band” approach championed by Du Bois. The dispute between Washington and Du Bois over tactics exposed the tensions that would divide the twentieth-century civil rights movement: militancy versus conciliation, separatism versus assimilation, social justice versus economic opportunities. By 1915, when Washington died, the leadership of the nation’s Black community was passing to Du Bois and others whose uncompromising effort to gain true equality signaled the beginning of the civil rights century.

Glossary

- Mississippi Plan (1890)

- Series of state constitutional amendments that sought to disenfranchise Black voters and was quickly adopted by nine other southern states.

- separate but equal

- Underlying principle behind segregation that was legitimized by the Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

- Wilmington Insurrection (1898)

- Led by Alfred Waddell in Wilmington, North Carolina, White supremacists rampaged through the Black community, overthrew the local government, and forced over 2,000 African Americans into exile.

- Atlanta Compromise (1895)

- Speech by Booker T. Washington that called for the Black community to strive for economic prosperity before demanding political and social equality.