![]() Spain in the New World

Spain in the New World

How did the Spanish conquer and colonize the Americas?

THE SPANISH EMPIRE

Throughout the sixteenth century, Spain struggled to manage its colonial empire while trying to repress the Protestant Reformation. Between 1500 and 1650, some 450,000 Spaniards, most of them poor, single, unskilled men, made their way to the colonies in the Western Hemisphere. Once there, through a mixture of courage, cruelty, piety, and greed, they shipped some 200 tons of gold and 16,000 tons of silver to Spain, which helped fuel the nation’s “Golden Empire” and trigger the emergence of capitalism in Europe, enabling new avenues for trade, investment, and unimagined profits. By plundering, conquering, and colonizing the Americas and converting and enslaving its inhabitants, the Spanish planted Christianity in the Western Hemisphere and gained the financial resources to rule the world.

CLASH OF CULTURES

The Caribbean Sea was the gateway through which Spain entered the Americas. After establishing a trading post on Hispaniola, the Spanish proceeded to colonize Puerto Rico (1508), Jamaica (1509), and Cuba (1511–1514). As its colonies multiplied to include Mexico, Peru, and what would become the American Southwest, the monarchy created an administrative bureaucracy to govern them and a name to encompass them: New Spain.

Many of the Europeans in the first wave of settlement in the New World died of malnutrition or disease. But the Native Americans suffered far more casualties, for they were ill-equipped to resist the European invaders. Civil disorder, rebellion, and tribal warfare abounded, leaving them vulnerable to division and foreign conquest. Attacks by well-armed soldiers and deadly germs from Europe overwhelmed entire indigenous societies.

CORTÉS’S CONQUEST

The most dramatic European conquest of a formidable Indian civilization occurred in Mexico. On February 18, 1519, Hernán Cortés, a Spanish soldier of fortune who went to the New World “to get rich, not to till the soil like a peasant,” sold his Cuban lands to buy ships and supplies, then set sail—without royal authority—for Mexico and its fabled riches. Cortés’s eleven ships carried nearly 600 soldiers and sailors, as well as 200 indigenous Cuban laborers, sixteen warhorses, greyhound fighting dogs, and cannons.

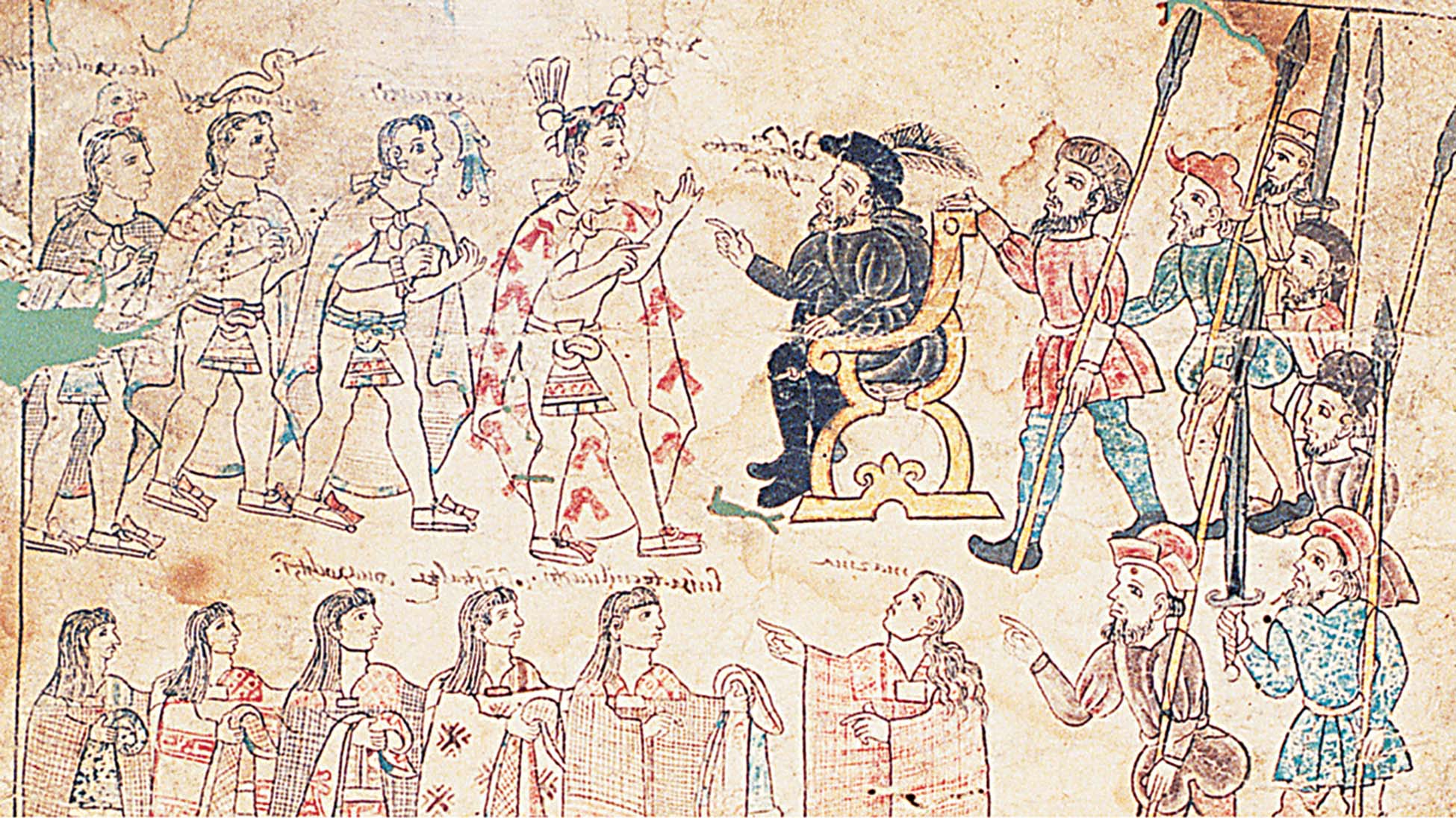

![]() Cortés and the Aztecs

Cortés and the Aztecs

The Spaniards first stopped on the Yucatan Peninsula, where they defeated a group of Maya. To appease his European conqueror, the vanquished chieftain gave Cortés twenty enslaved young women. The Spanish commander distributed them to his captains but kept one of the girls (“La Malinche”) for himself and named her Doña Marina. Malinche spoke Mayan as well as Nahuatl, the language of the Mexicas, with whom she had previously lived. She became Cortés’s interpreter—and mistress; later she would bear the married Cortés a son.

After leaving Yucatan, Cortés sailed west and landed at a place he named Veracruz (True Cross). There he convinced the local Totonacs to join his assault against the Mexicas, their hated rivals. To prevent his soldiers, called conquistadores (conquerors), from deserting, Cortés ordered the Spanish ships burned. He spared only one vessel to carry the expected riches back to Spain. Conquistadores were then widely recognized as the best soldiers in the world. They received no pay; they were pitiless professional warriors willing to risk their lives for a share in the expected plunder. One conquistador explained that he went to America “to serve God and His Majesty, to give light to those who were in darkness, and to grow rich, as men desire to do.”

With his small army and thousands of Indian allies, Cortés brashly set out to conquer the sprawling Mexica Empire, which extended from central Mexico to what is today Guatemala. The army’s nearly 200-mile march through the mountains to the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlán took almost three months.

Spanish Invaders

As the Spanish army marched across Mexico, the conquistadores heard fabulous stories about Tenochtitlán, with its gleaming white buildings and beautiful temples. With some 200,000 inhabitants scattered among twenty neighborhoods, it was larger than London, Paris, and Seville, the capital of Spain. Laid out in a grid pattern on an island in a shallow lake, divided by long cobblestone avenues, crisscrossed by canals, connected to the mainland by wide causeways, and graced by formidable stone pyramids, the city seemed impregnable. Cortés wrote that the “floating city” was “so big and so remarkable” that it “was unbelievable.” A conquistador reported that their first glimpse of the city left them speechless: “We did not know what to say or whether what appeared before us was real.”

The Mexicas viewed themselves as having created the supreme civilization on the planet. “Are we not the masters of the world?” the emperor, Moctezuma II, said to his ruling council when he learned that the Europeans had landed on the coast. Through a combination of threats and deceptions, the Spanish entered Tenochtitlán peacefully. Moctezuma mistook Cortés for the exiled god of the wind and sky, Quetzalcoatl, come to reclaim his lands. The emperor stared at the newcomers with their long hair, sharp metal swords, gunpowder, and wheeled wagons. He gave the Spaniards a lavish welcome, housing them close to the palace and providing gifts of gold and women.

Within a week, however, Cortés executed a palace coup, taking Moctezuma hostage. He then ordered religious statues destroyed and coerced Moctezuma to end the ritual sacrifices of prisoners of war. Cortés explained why the invasion was necessary: “We Spaniards have a disease of the heart that only gold can cure.”

The Mexicas Fight Back

For eight months, Cortés tried to convince the Mexicas to surrender, but they instead decided that Moctezuma was betraying them and resolved to resist the invaders. In the spring of 1520, the Spaniards attacked the Mexicas and killed many of the ruling elite. The Mexicas fought back, however, prompting Cortés to march Moctezuma to the edge of a balcony and force him to order the warriors to lay down their weapons. “We must not fight them,” the emperor shouted. “We are not their equals in battle. Put down your shields and arrows.” The priests, however, denounced Moctezuma as a traitor and stoned him to death.

For the next seven days, Mexica warriors forced the Spaniards to retreat after suffering heavy losses. Their 20,000 Indian allies remained loyal, however, enabling Cortés to regroup his forces. Sporadic fighting continued for months. In 1521, having been reinforced with more soldiers and horses from Cuba and thousands more indigenous warriors eager to defeat the despised Mexicas, Cortés surrounded the imperial city for eighty-five days, cut off the city’s access to water and food, and watched as a smallpox epidemic devastated the inhabitants, killing 90 percent of them.

The Biological and Military Defeat of Tenochtitlán

The ravages of smallpox and the support of thousands of Indian allies help explain how such a small force of well-organized and highly disciplined Spaniards vanquished a proud imperial nation in August 1521. After 15,000 Mexicas were slaughtered, the others surrendered. A merciless Cortés ordered the leaders hanged and the priests devoured by dogs, but not before torturing them (literally putting their feet to the fire) in an effort to learn where more gold might be found. A conquistador remembered that the streets “were so filled with sick and dead people that our men walked over nothing but bodies.” In two years, Cortés and his army had waged a genocidal war and seized an epic empire that had taken centuries to develop.

Cortés became the first governor-general of New Spain and quickly began replacing the Mexica leaders with Spanish bureaucrats and church officials. Mexico City became the imperial capital of New Spain, and Cortés ordered that a grand Catholic cathedral be built from the stones of Moctezuma’s destroyed palace.

PIZZARO’S INVASION OF THE INCAN EMPIRE

Cortés’s conquest of Mexico established the model for waves of plundering conquistadores to follow. Within fifty years, Spain had established a vast empire in Mexico and Central America, the Caribbean, and South America—calling it New Spain. The Spanish cemented control of their empire in the Americas through ruthless violence and enslavement of the indigenous peoples followed by oppressive rule over them—just as the Mexicas had done in forming their empire.

In 1531, Francisco Pizarro mimicked the conquest of Mexico when he led a band of 168 conquistadores down the Pacific coast of South America. They brutally subdued the extensive Incan Empire and its 5 million people living in present-day Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Colombia, Chile, and Argentina. The Spanish killed thousands of Incan warriors, seized imperial palaces, took royal women as mistresses and wives, and looted the empire of its gold and silver.

From Peru, Spain extended its control southward through Chile and north to present-day Colombia. A government official in Spain reported in 1534 that the amount of gold and silver flowing into the treasury “was incredible.”

SPANISH AMERICA

As the sixteenth century unfolded, the Spanish shifted from looting the indigenous peoples to enslaving them. To reward the conquistadores, the Spanish government transferred to America a medieval socioeconomic system known as the encomienda. Favored soldiers or officials received large parcels of land—and control over the people who lived there. The conquistadores were told to Christianize the Indians and provide them with protection in exchange for “tribute”—a share of their goods and their forced labor.

New Spain thus became a society of extremes: wealthy encomenderos and powerful priests at one end, and Indians held in poverty at the other. The Spaniards used brute force to ensure that the Indians accepted their role. Nuño de Guzman, a governor of a Mexican province, loved to watch his massive fighting dog tear apart rebellious Indians. He was equally brutal with colonists. After a Spaniard talked back to him, he had the man nailed to a post by his tongue.

IMPOSING THE CATHOLIC RELIGION

Once in control of the Americas, the Spanish sought to convert the Indians into obedient Catholics. Hundreds of priests fanned out across New Spain, using force to convert the Indians. “Though they seem to be a simple people,” a priest declared in 1562, “they are up to all sorts of mischief, and without compulsion, they will never speak the [religious] truth.” By the end of the sixteenth century, there were more than 300 Catholic monasteries or missions in New Spain. Catholicism had become a major instrument of Spanish imperialism and the most important institution in the Americas.

Some officials criticized the forced religious conversion of Indians and the harsh encomienda system. A Catholic priest, Bartolomé de Las Casas, was horrified by the treatment of Indians in Hispaniola and Cuba. The conquistadores behaved like “wild beasts,” he reported, “killing, terrorizing, afflicting, torturing, and destroying the native peoples.” Las Casas insisted that the role of Spaniards in the New World was to convert the Indians, “not to rob, to scandalize, to capture, or destroy them, or to lay waste their lands.” In 1514, he resolved to devote himself to aiding the Indians.

Las Casas spent the next fifty years advocating better treatment for indigenous people, earning the title Protector of the Indians. He urged that the Indians be converted to Catholicism only through “peaceful and reasonable” means, and he eventually convinced the monarchy and the Catholic Church to issue new rules calling for better treatment of the Indians. Still, the use of “fire and the sword” continued, and angry Spanish colonists on Hispaniola banished Las Casas from the island.

On returning to Spain, Las Casas said, “I left Christ in the Indies not once, but a thousand times beaten, afflicted, insulted and crucified by those Spaniards who destroy and ravage the Indians.” In 1564, two years before his death, he bleakly predicted that “God will wreak his fury and anger against Spain some day for the unjust wars waged against the Indians.”

Glossary

- conquistadores

- Term from the Spanish word for “conquerors,” applied to Spanish and Portuguese soldiers who conquered lands held by indigenous peoples in central and southern America as well as the current states of Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and California.

- encomienda

- A land-grant system under which Spanish army officers (conquistadores) were awarded large parcels of land taken from Native Americans.