GROWTH IN THE COLONIES

What were the major factors that contributed to the demographic changes in the English colonies during the eighteenth century?

THE DEMOGRAPHY OF THE EARLY COLONIES

The early British American colonial population encompassed several dynamic groups of people. They arrived with different dreams and aspirations, and those who were already there had to make sense of the newcomers. As the population grew, people found ways to interact with one another through social, labor, and prescribed gender routines. Their roles shifted as it became necessary to adapt to an expanding economy and to accommodate new arrivals. Even with a disparate population, political and religious life remained central to the shaping of early America.

More information

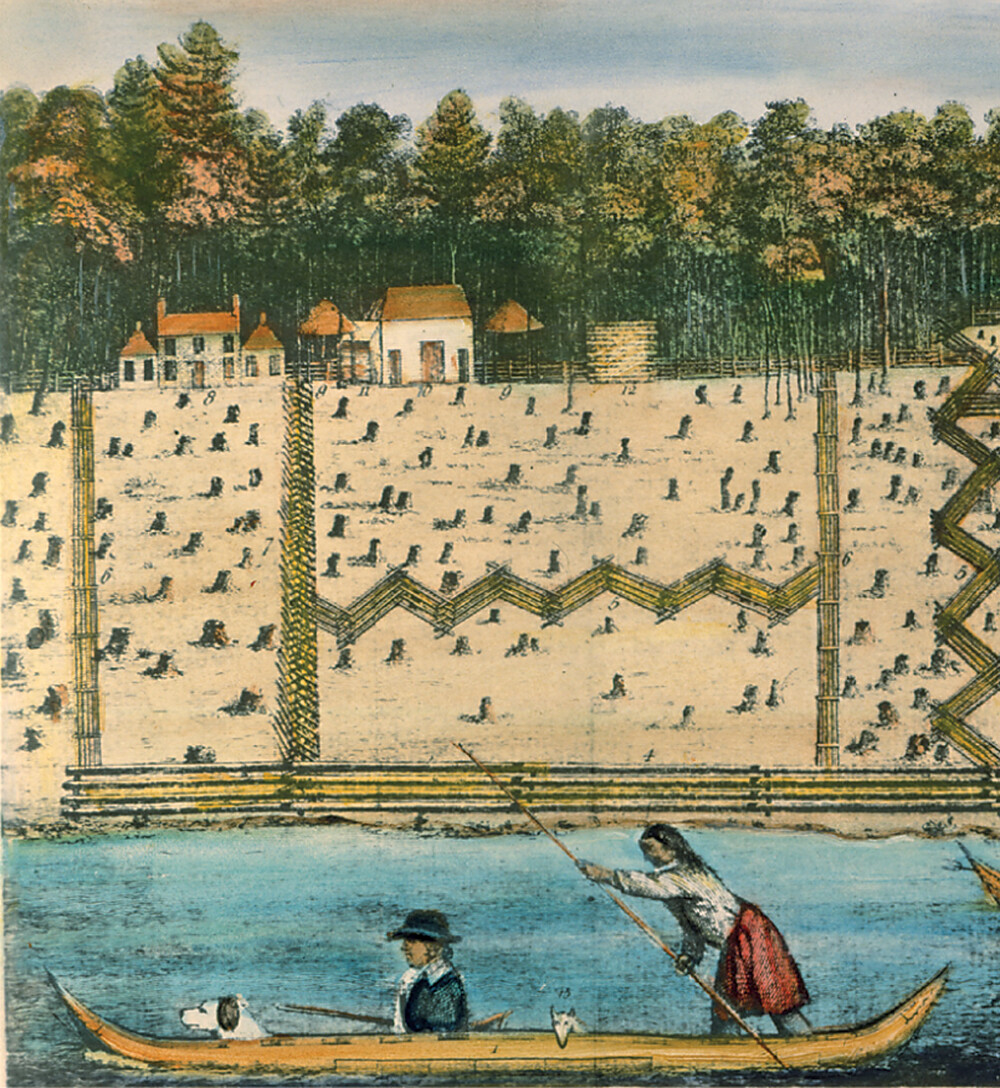

A region of clear cut land borders a river in the foreground and a dense forest in the background. A man, a woman, and their dog row along the river in a canoe. The land behind them is lined with tree stumps, and is segmented into smaller sections by fencing. A large, colonial era house appears beyond the clear cut land.

POPULATION GROWTH

Life in British America was hard. Many of the first colonists died of disease or starvation; others were killed by Indigenous Americans defending their native lands. The average death rate during the early years of settlement was 50 percent. Once colonial life became more settled, however, the population grew rapidly. On average, it doubled every twenty-five years. By 1750, the number of colonists had passed 1 million; by 1775, it approached 2.5 million. In comparison, the combined population of England, Scotland, and Ireland in 1750 was 6.5 million. An English visitor reported in 1766 that America would surely become “the most prosperous empire the world had ever seen.” But that would mean trouble for Britain: “How are we to rule them?”

Benjamin Franklin, a keen observer of life in British America, said that the colonial population grew so rapidly because land was plentiful and cheap, while laborers were scarce and costly. In contrast, Europe suffered from overpopulation and expensive farmland. From this reversal of conditions flowed many of the changes that European culture underwent during the colonization of America—not the least being that land and good fortune lured enterprising immigrants and led the colonists to have large families, in part because farm children could help work in the fields or they could purchase enslaved people to perform the necessary labor.

BIRTH AND DEATH RATES

Colonists tended to marry and start families at an earlier age than was common in Europe. In England, the average age at marriage for women was twenty-five or twenty-six; in America, it was twenty. The birth rate rose accordingly, since women who married earlier had time for about two additional pregnancies during their childbearing years. On average, a married woman had a child every two to three years before menopause. Some women had as many as twenty pregnancies. Abiah Folger, Benjamin Franklin’s mother, for example, bore sixteen children; his grandmother Mary Folger had seventeen.

More information

A painted portrait of a woman wearing a long, black dress, a tight necklace, and her hair in an updo. The collar and cuffs of her dress are lined with white lace.

More information

A painted portrait of a woman wearing a black lace shawl over a thick, white shirt. Her white hair is tied back into a gray hat, which has been embellished with tulle.

Birthing children was dangerous, however, since most babies were delivered at home—and often in unsanitary conditions. Miscarriages were common. Between 25 and 50 percent of women died during childbirth or soon thereafter, and almost a quarter of all babies did not survive infancy during the early stages of colonial settlement.

Disease and epidemics were common. Half the children born in Virginia and Maryland died before reaching age twenty. In 1713, Boston minister Cotton Mather lost three of his children and his wife to a measles epidemic. (Overall, Mather lost eight of fifteen children in their first year of life.) Martha Custis, the Virginia widow who married George Washington, had four children during her first marriage. They all died young, at ages two, three, sixteen, and seventeen.

Over time, however, infants had a better chance of reaching maturity in New England than in England, and adults lived longer in the colonies. Lower mortality rates in the colonies resulted from several factors. Because fertile land was plentiful, famine seldom occurred after the early years of colonization; and although the winters were more severe than in England, firewood was abundant. Being younger (the average age in 1790 was sixteen), Americans were less susceptible to disease than were Europeans. The fact that they were more scattered than in Europe also meant they were less exposed to infectious diseases. However, that fact of life began to change as colonial cities grew larger and more densely populated. By the mid-eighteenth century, the colonies experienced levels of disease much like those in Europe.

IMMIGRANTS AND CITIZENSHIP

High rates of immigration from Europe to the British American colonies across the eighteenth century continued to drive the overall population upward. Mr. Wortley Montagu introduced a bill for the Naturalizing Foreign Protestants who “might endanger our ancient polity and government, and by frequent intermarriages go a great way to blot out and extinguish the English race.”

To sustain high levels of immigration to British America, Parliament in 1740 passed the Naturalization Act. It announced that immigrants living in America for seven years would become subjects in the British Empire after swearing a loyalty oath and providing proof that they were Protestants. While excluding “papists” (a disparaging term for Roman Catholics), the law did make exceptions for Jews.

NATIVISM

Nativism, a prejudice against particular groups of immigrants, emerged in the colonies as the population grew. For example, as the number of desperately poor Irish immigrants soared, so, too, did prejudice against them. In 1726, Benjamin Franklin, then twenty years old, watched as a shipload of Irish immigrants disembarked in New York City. He wondered how the more affluent passengers could have put up with being “confined and stifled up with such a lousy, stinking rabble.”

Still, the Irish and Scots-Irish kept coming. An Irish immigrant in New York wrote home to his minister, urging him to “tell all the poor folk . . . that God has opened a door for their deliverance” in America. (Scotch-Irish is the more common but inaccurate name for the Scots-Irish, the mostly Presbyterian population that the British government transplanted from Scotland to the province of Ulster, in northern Ireland, to “protestantize” Catholic Ireland.)

As another example, although Pennsylvania was founded as a haven for all people, by the mid-eighteenth century concerns arose about the influx of Germans. Benjamin Franklin described the German arrivals as “the most ignorant stupid sort of their own nation.” He feared that they would “soon outnumber us” and be a source of constant tension. Why, Franklin asked, “should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens?” He was “not against the admission of Germans in general, for they have their Virtues,” but he urged that they be spread across the colonies so as not to allow them to become a majority anywhere.

Overall, the demographic changes in the colonies during the eighteenth century reflected a combination of factors. Population growth increased through the lure of cheap land, which attracted more immigrants. At the same time, increased numbers of women coming to the colonies meant more marriages, more children, and larger families—despite an initial death rate higher than Europe’s. Gradually the death rate dropped, a result of fewer famines and the robustness of the mostly young colonists, who were less susceptible to disease. As the population expanded with many poor immigrants seeking better opportunities, colonists developed prejudice against some groups.

Glossary

- death rate

- The proportion of deaths per 1,000 of the total population; also called the mortality rate.

- birth rate

- The proportion of births per 1,000 of the total population.