FIVE PRINCIPLES OF POLITICS

Politics possesses an underlying logic that can be understood in terms of five simple principles:

- All political behavior has a purpose (the rationality principle).

- Institutions structure politics (the institution principle).

- All politics is collective action (the collective action principle).

- Political outcomes are the products of individual preferences, institutional procedures, and collective action (the policy principle).

- How we got here matters (the history principle).

Some of these principles may seem obvious or abstract. They are useful, however, because they each possess a distinct kernel of truth, on the one hand, and are sufficiently general to help us understand politics in a variety of settings, on the other hand. Armed with these principles, we can perceive order within the apparent chaos of political events and processes whenever and wherever they take place.

The Rationality Principle: All Political Behavior Has a Purpose

All people have goals, and these goals guide their political behavior. For many citizens, political behavior is as simple and familiar as reading news headlines on Twitter or discussing political controversies with a neighbor. Beyond these basic acts, political behavior broadens to include explicitly political activities that require some forethought, such as watching a political debate on television, arguing about politics with a coworker, signing a petition, or attending a city council meeting. Political behavior requiring even more effort includes casting a vote in the November election (having first registered to vote in a timely manner), contacting legislative representatives about a political issue, contributing time or money to a political campaign, or even running for local office.

Some of these acts require time, effort, financial resources, and resolve, whereas others place only small, even insignificant, demands on a person. Nevertheless, all of them are done for specific reasons. They are not random; they are not entirely automatic or mechanical, even the smallest of them. They are purposeful. Sometimes people engage in these activities for the sake of entertainment (reading the front page in the morning) or just to be sociable (chatting about politics with a neighbor, coworker, or family member). At other times, people engage in them explicitly because they are political—because someone cares about, and wants to influence, an issue, a candidate, a party, or a cause. We will treat all of this political activity as purposeful, as goal-oriented. Indeed, our attempts to identify the goals of various political activities will help us understand them better.

The political activities of ordinary citizens are hard to distinguish from conventional everyday behavior—reading newspapers, swiping through social media, streaming the news, discussing politics, and so on. For the professional politician, on the other hand—the legislator, executive, judge, party leader, bureau chief, or agency head—nearly every act is explicitly political. The legislator’s decision to introduce a particular piece of legislation, give a speech in the legislative chamber, move an amendment to a pending bill, vote for or against a bill, or accept a contribution from a particular group requires their careful attention. There are pitfalls and dangers, and the slightest miscalculation can have huge consequences. If the legislator introduces a bill that appears to be too pro-labor in the eyes of their constituents, for example, before they know it, their opponent in the next election is charging them with being too cozy with the unions. If they give a speech against job quotas for historically marginalized groups, they risk alienating the marginalized communities in their state or district. If they accept campaign contributions from industries known to pollute, environmentalists will think they are no friend of the earth. Because nearly every move is fraught with risks, legislators make their choices with forethought and calculation. Their actions are, in a word, instrumental. Politicians think through the benefits and costs of each decision, speculate about and weigh the probabilities of future effects, and consider the risks of the decision in order to determine the personal value of the potential outcomes.

As examples of instrumental behavior, consider elected officials more generally. Most politicians want to keep their positions or move up to more important positions. They like their jobs for a variety of reasons—the salaries, privileges, prestige, and opportunities for accomplishment that accompany them, to name just a few. So we can understand why politicians do what they do by thinking of their behavior as instrumental, with the purpose of keeping their jobs. This equation is quite straightforward with regard to elected politicians, who often see no further than the next election; they think mainly about how to prevail and who can help them win. “Retail” politics involves dealing directly with constituents, such as when a politician helps an individual navigate a federal agency or find a misplaced Social Security check. “Wholesale” politics involves appealing to collections of constituents, such as when a legislator introduces a bill that would benefit a group active in their state or district, secures money for a public building in their hometown, or intervenes in an official proceeding on behalf of an interest group that will, in turn, contribute to their next campaign. Politicians may do these things for ideological reasons; they may have policy and personal concerns of their own, after all. But ultimately, elections provide incentives for politicians to help their constituents; the more responsive politicians are to the people they represent, the more likely they are to win their next election. Elections and electoral politics are thus premised on instrumental behavior by politicians.

Political scientists explain the behavior of elected politicians by treating the “electoral connection” as their principal motivation.4 Elected politicians, in this view, base their behavior on the goal of maximizing votes at the next election or maximizing their probability of winning. Of course, other things motivate them as well—public policy objectives, power within their institution, and ambition for higher office.5 The fact is, however, that reelection is a necessary condition for pursuing any of the other objectives.6

But what about political actors who are not elected? What do they want? Consider a few examples:

- Agency heads and bureau chiefs, motivated by policy preferences and power, seek to maximize their budgets.

- Legislative committee chairs (who are elected to Congress but appointed to committees) are “turf minded,” intent on maximizing their committee’s policy jurisdiction and their own influence in it.

- Voters, motivated by their personal welfare as well as their beliefs about “what’s best for the country,” cast ballots to elect officials who will shape government policy in ways that will benefit them.

- Justices, serving lifetime terms, seek to maximize the prospects for their interpretation of the Constitution to prevail.7

In each instance, we can postulate motivations that fit the political context. These goals often have a strong element of self-interest, but they may also incorporate “enlightened self-interest.” That is, these political actors may include the welfare of others such as their families, the entire society, or even all of humanity among their motivations.

The Institution Principle: Institutions Structure Politics

In pursuing political goals, people—especially elected leaders and other government officials—confront certain recurring problems, and they develop standard ways of addressing them. Routinized, structured processes for pursuing goals and addressing recurring problems are what we call institutions. Institutions are the rules and procedures that provide incentives for political behavior, thereby shaping politics. Institutions may have salutary effects—discouraging conflict, facilitating coordination, and enabling bargaining. Of course, institutions may have pernicious effects too—providing the means for private gain at public expense (corruption), erecting barriers against voting and other forms of collective action, or undermining leadership. In short, institutions structure and incentivize behavior, sometimes for good, other times for ill.

Institutions are part script and part scorecard. As scripts, they choreograph political activity. As scorecards, they list the players, their positions, what they want, what they know, and what they can do. As a consequence, institutions matter. The U.S. Senate, for example, was one kind of legislative body when its members were elected to their positions by state legislatures; it has become quite a different kind of legislative body now under the alternative electoral institution in which its members are popularly elected by voters in each state. To take another example of how institutions matter, consider how the institution of term limits affects the power of an executive such as a mayor, governor, or president in her last term. A prohibition against running for reelection weakens an executive by removing the leverage they might have had if there were the possibility of securing another term in office; it also weakens the capacity of voters to hold them accountable for their actions during their last term.

Although the Constitution sets the broad framework for American political institutions, much adaptation takes place as strategic political actors bend the institutions for their own various purposes. We focus here on four ways in which institutions provide politicians with the necessary authority to pursue public policies: jurisdiction, agenda and veto power, decisiveness, and delegation.

Jurisdiction. A critical feature of an institution is the domain over which its members have the authority to make decisions. Political institutions are full of specialized jurisdictions controlled by various individuals or subsets of members. One feature of the U.S. Congress, for example, is its standing committees, each of whose jurisdictions is carefully defined by official rules. Most members of Congress become specialists in all aspects of their committees’ jurisdictions, and they often seek committee assignments based on the subjects in which they want to specialize. Committees are granted the authority to set the agenda of the larger parent chamber when it comes to issues falling under their jurisdiction. For example, proposed legislation related to the military must pass through the Armed Services Committee before the entire House or Senate can consider it. In this way the congressional structure of jurisdiction-specific committees affects the politics of the institution as a whole. Similarly, a bureau or agency is established by law, and its jurisdiction is firmly fixed. For example, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) possesses the authority to regulate the marketing of pharmaceuticals but is not permitted to regulate products falling outside its jurisdiction.8 Also falling within its jurisdiction is the authority to declare vaccines (like the ones for COVID-19) safe and effective for general public use.

Agenda Power and Veto Power. Agenda power describes who determines what will be taken up for consideration in an institution. Those who exercise some form of agenda power are said to engage in gatekeeping. They determine which items may pass through the gate and move onto the institution’s agenda and which alternatives will have the gate slammed in their face. Gatekeeping, in other words, consists of the power to make proposals and the power to block proposals from being made. The ability to keep something off an institution’s agenda should not be confused with veto power, which is the ability to defeat something even if it does become part of the agenda. In the legislative process, for example, the president has no general gatekeeping authority—he has no agenda power and thus cannot force the legislature to take up a proposal or block it from considering something—but he does have (limited) veto power. Congress, in contrast, controls its own agenda; its members can place matters on the legislative agenda. No other institutions can prevent Congress from passing a measure, but a presidential veto can prevent a measure, once passed, from becoming the law of the land. Thus, when it comes to legislation, agenda power is vested in the legislature. Both the legislature and the president possess veto power; the assent of each is required for a bill to become a law. We will examine these processes in more detail in Chapters 6 and 7.

Decisiveness. Another crucial feature of an institution is its body of rules for making decisions. The more an organization values participation by a broad range of its members, for example, the more it requires rules that balance desired participation with the need to bring input or debate to a close so that decisions can be made. This is why it is possible on the floor of a legislature to “move” the question under discussion, a motion to close the debate and move immediately to a vote.9 In some legislatures, though, inaction seems to take precedence over action; in the U.S. House of Representatives, for example, a motion to adjourn (and thus not vote on a measure) takes precedence over a motion to move to a vote. In the U.S. Senate, to take another example, a supermajority (60 votes) is required to close debate, so a minority of members can obstruct proceeding to make a decision. Decisiveness rules thus specify when votes may be taken, the sequence in which votes may occur, and—most important—how many individuals supporting a motion are sufficient for it to pass.

Delegation. A final aspect of institutional authority concerns delegation. Representative democracy is the quintessential instance of delegation. Citizens, through elections, delegate to representatives—chiefly legislators and executives—the authority to make decisions on their behalf rather than exercising political authority directly. We can think of our political representatives as our agents, just as we may think of professionals and craftspeople (doctors, accountants, plumbers, and so on) as agents whom we hire to act on our behalf. Why would those with authority, whom we will call principals, delegate some of their authority to agents? The answer is that both principals and agents benefit from it. Principals benefit because they are able to off-load to specialists tasks that they themselves are less capable of performing. Ordinary individuals, for example, aren’t as versed in the tasks of governance as professional politicians are, just as they aren’t as versed in the job of fixing a burst water pipe as a plumber is. Agents benefit from delegation as well, since it puts their services in demand, enables them to exercise authority, and compensates them for their efforts. Delegation, with its division and specialization of labor, is thus the rationale for representative democracy.

Examples of principals and agents abound in politics. Elected officials, as just noted, are agents for citizen principals. Leaders are agents for their followers. Government bureaus—called agencies after all—serve as agents for elected principals in the executive and legislative branches.10 Law clerks are agents for the judges who employ them. Lobbyists are agents of special interests. In short, the political world is replete with links between principals and agents.

The relationship between a principal and an agent allows the former to delegate to the latter, with benefits for both. But there is a dark side to this principal-agent relationship. As the eighteenth-century economist Adam Smith noted in The Wealth of Nations (1776), economic agents are not motivated by the welfare of their customers to grow vegetables, make shoes, or weave cloth; rather, they do those things out of their own self-interest. Thus, when delegating to agents, a principal must take care that those agents are properly motivated to serve the principal’s interests, either by sharing those interests or by deriving something of value for acting to advance them. The principal will need instruments by which to monitor what their agents are doing and then reward or punish them accordingly. Nevertheless, a principal will never eliminate entirely the possibility that their agents could deviate from their interests because of the transaction costs that would be involved. The effort necessary to negotiate and then police every aspect of a principal-agent relationship becomes, at some point, more costly than it is worth.

In sum, the upside of delegation is that specific activities will be assigned to precisely those agents who possess a comparative advantage in performing them. The downside is that there is a chance that the agents’ goals will not align with the principals’ goals, and thus there is a possibility that agents will march to the beat of their own drummers. Delegation is a double-edged sword.

Characterizing institutions in terms of jurisdiction, agenda and veto power, decisiveness, and delegation covers an immense amount of ground—there are many ways to structure an institution in terms of these four characteristics. We also want to make clear that institutions not only make rules for governing but also present strategic opportunities for various political interests, depending on how the institutions are designed. As George Washington Plunkitt, the savvy political boss of Tammany Hall, said of the institutional situations in which he found himself, “I seen my opportunities, and I took ’em.”11 In short, do institutions matter? Absolutely.

The Collective Action Principle: All Politics Is Collective Action

Political action is collective: it involves building, combining, mixing, and amalgamating people’s individual goals. It sometimes occurs in highly institutionalized settings—a committee, legislature, or bureaucracy, for example. However, it also occurs in less institutionalized settings—a campaign rally, a get-out-the-vote drive, or a civil rights march. Moreover, collective action can be difficult to orchestrate because the individuals involved often have different goals, preferences, and motives for cooperation. Conflicting goals are inevitable; the question is how they can be accommodated. The most typical means of resolving collective dilemmas is bargaining among individuals. But when the number of parties involved is too large for face-to-face bargaining, there must be a shared incentive to motivate everyone to act collectively.

Informal Bargaining. Political bargaining may be highly formal or entirely informal. We engage in informal bargaining often in our everyday lives. One of this book’s authors, for example, shares a hedge on his property line with one of his neighbors. First one takes responsibility for trimming the hedge and then the other, alternating from year to year. This arrangement (or bargain) is merely an understanding, not a legally binding agreement, and it was reached amicably and without much fuss or fanfare after a brief conversation. No organized effort—such as hiring lawyers; drafting an agreement; and having it signed, witnessed, notarized, and filed at the county courthouse—was required.

Bargaining in politics can be similarly informal. Whether called horse trading, back-scratching, logrolling, or wheeling and dealing, it has the same flavor as the casual negotiation between neighbors. Deals will be struck depending on the participants’ preferences and beliefs. If preferences are incompatible or beliefs inconsistent with one another, then a deal among participants simply may not be possible. If the participants’ preferences and beliefs are not too far out of line, then there will be a range of possible bargaining outcomes, some advantaging one party, others advantaging other parties. In short, there will be room for a compromise. In situations of repeated informal bargaining, regular practices often emerge as ways of coming to an agreement—what the locals would say are “ways of doing things around here.” Examples include taking turns, splitting the difference, or flipping coins.

In fact, much of politics is informal, unstructured bargaining. First, many disputes subject to bargaining are of sufficiently low impact that establishing formal machinery for dealing with them is not worth the effort. Rules of thumb (or norms) such as the shortcuts just mentioned often develop as benchmarks for dealing with certain types of conflicts. Second, repetition can contribute to successful cooperation. If a small group engages in bargaining today over one matter and tomorrow over another—as neighbors bargain over draining a swampy meadow one day, fixing a fence another, and trimming a hedge on yet another—then patterns develop. If one party constantly tries to extract maximal advantage, then the others will cease doing business with that party. If, however, each party “gives a little to get a little,” then a pattern of cooperation develops. It is the repetition of similar, mixed-motive occasions that allows this pattern to emerge without formal trappings. Many political circumstances either are amenable to informal rules or are repeated often enough to allow cooperative patterns to emerge.12

Formal Bargaining. Other bargaining situations are governed by rules. The rules describe such things as who gets to make the first offer, how long the other parties have to consider it, whether other parties can make counteroffers, the method by which parties convey assent or rejection, what happens when all (or some decisive subset) of the others accept an offer, and what happens next if the proposal is rejected. It may be hard to imagine two neighbors deciding how to trim their common hedge under procedures as explicit as these. It is more plausible, however, to imagine a bargaining session between labor and management over wages and working conditions at a large manufacturing plant proceeding in just this manner. The distinction suggests that some bargaining is more suited to formal proceedings, whereas other bargaining situations can be resolved well enough without them. The same may be said about personal situations that involve bargaining. A married couple is likely to divide household chores by informal bargaining, but this same couple would employ a formal procedure if they were dividing household assets in a divorce settlement.

Formal bargaining is often associated with events in official institutions—legislatures, courts, party conventions, administrative agencies, and regulatory agencies, for instance. In these settings, situations involving mixed motives arise repeatedly. Year in and year out, legislatures pass statutes, approve executive budgets, and oversee the administrative branch of government. Courts administer justice, determine guilt or innocence, resolve differences between disputants, and render interpretive opinions. Party conventions nominate candidates and approve their campaign platforms. Administrative and regulatory agencies implement policy and make rulings about its applicability. All of these are mixed-motive circumstances in which different parties have different goals; thus, while gains from cooperation are possible, bargaining failures are also a definite possibility. In general, the formal bargaining that takes place within institutions is governed by rules that regularize proceedings, both to maximize the prospects of reaching agreement and to guarantee that procedural wheels are already in place each time a similar bargaining problem arises. This is our first application of the institution principle: institutions facilitate (but do not always succeed in producing) collective action.

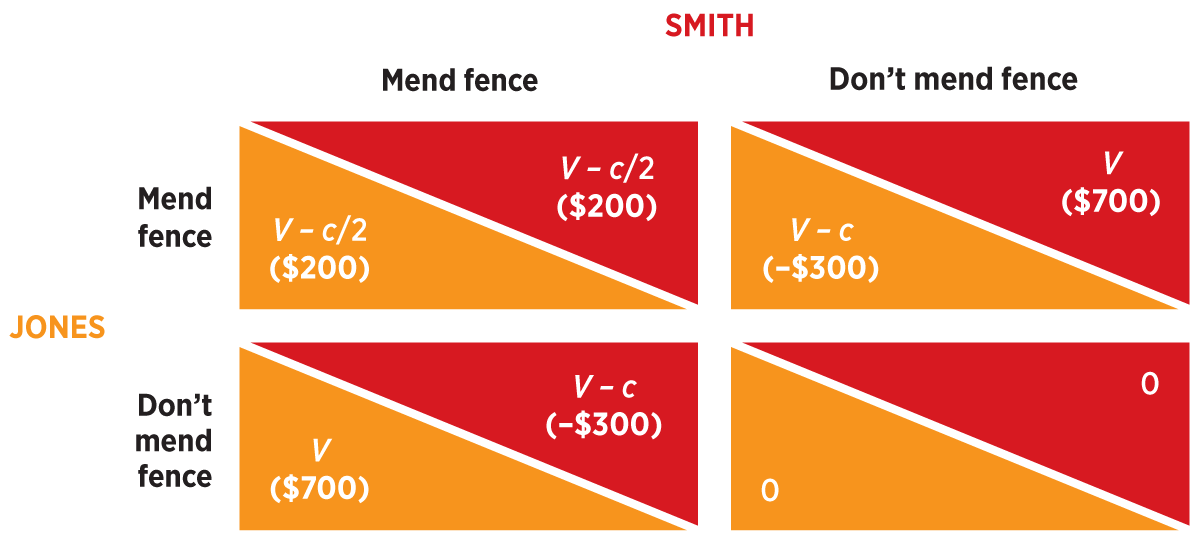

Collective Dilemmas and Bargaining Failures. Even when gains are possible from collective action—when people share some common objective, for example—it still may not be feasible to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion. Consider two farmers, Farmer Jones and Farmer Smith, interested in mending a fence that separates their properties. Suppose that the farmers each value the mended fence at some positive amount, V. Suppose that the total cost (in terms of time or effort) to do this chore is c, a big enough cost to make the job not worth the effort if a farmer had to do it all by himself. For example, if each farmer values the mended fence at $700, but the cost of one of them to repair it on his own is $1,000, the net benefit to one farmer repairing it alone ($700 – $1,000) is less than zero—and thus not an attractive option. If they shared the cost equally, though, their net benefit each would be the value of the mended fence minus the total cost split by the two of them: V – c/2, in our example, $700 – $500—a positive net benefit of $200 to each. If one of the farmers, however, could off-load the entire project on his neighbor, then he would not have to bear any of the cost and would still enjoy the mended fence valued by him at V ($700). The situation is displayed in Figure 1.1. The two rows show the options available to Jones and the two columns show the options available to Smith. The lower-left entry in each cell is the payoff to Jones if he selects the row option and Smith selects the column option; the upper-right entry is Smith’s payoff in each scenario. Thus, if both choose to mend the fence (the upper-left cell), then they each enjoy a positive net benefit of V – c/2. If, however, Jones takes on the job but Smith does not (the upper-right cell), then Jones pays the full price and receives V – c (which is negative) and Smith gets the full value, V. The other two cells are filled in according to this logic.

FIGURE 1.1

A COLLECTIVE DILEMMA

Consider now how Jones might think about this problem. On the one hand, if Smith chooses to mend the fence (left column in the figure), then Jones gets V – c/2 if he helps Smith. But he does even better, getting the full value of V, if he lets Smith do the whole job. On the other hand, if Smith chooses not to mend the fence (right column in the figure), then Jones gets a negative value, V – c, if he does the job himself, but gets zero if he too does not take up the task. Putting these together, Jones realizes that no matter what Smith does, Jones is better off not mending the fence. Following the same logic, Smith will arrive at the same conclusion. So each chooses “don’t mend the fence,” and each gets a payoff of zero, even though both would have been better off if both had chosen “mend the fence.”

This is a famous dilemma in social science.13 It is a dilemma because the two individuals share a common goal—a mended fence—but each person’s individual rationality causes both of them to do worse than they would have done had they “suspended” their rationality and contributed to the common objective. Even if the two farmers tried to overcome this dilemma, the dilemma persists, as each has a rational temptation to defect from a bargain in which both agree to mend the fence. Moreover, each is likely nervous that the other will defect, given the incentives of the situation, and so feels compelled to defect himself.

The broad point of this example is that even common values and objectives do not guarantee that a positive outcome will result from bargaining. We encounter dilemmas and bargaining failures frequently in politics, but some methods exist that can partially mitigate these failures.

Collective Action, Free Riders, Public Goods, and the Commons. The idea of political bargaining suggests an intimate kind of politics, involving face-to-face relations, negotiation, compromise, give-and-take, and so on. Such bargaining results from the combination of mixed motives and small numbers. When the number of individuals or other actors involved becomes large, bargaining may no longer be practical. If 100 people own property bordering a swampy meadow, how does this community solve the swamp’s mosquito problem? How does the community secure the benefits that arise from cooperation? In short, what happens if a simple face-to-face interaction, possibly amenable to bargaining, now requires coordination among a large number of people? How does a community become a community and not just a collection of individuals?

In the swampy meadow example, everyone shares some common value—eliminating the mosquito habitat—but they may disagree on other matters. Some may want to use pesticides; others may be concerned about the environmental impact. And there are bound to be disagreements over how to pay for the project. A collective action problem arises, as in this example, when there is something to be gained if group members can cooperate and assure one another that no one will get away with bearing less than their fair share of the effort.

Groups of individuals intent on collective action ordinarily establish decision-making procedures: relatively formal arrangements by which to resolve differences, coordinate the group to pursue a course of action, and sanction slackers. Workers in a manufacturing plant may attempt to form a union; like-minded citizens may organize a political party. Most groups will also require a leadership structure, which is necessary to deal with a phenomenon known as free riding. To return to our example, if one or a few of the landowners bordering the swamp were to clear the mosquitos alone, their actions would benefit the other owners as well. The other owners would be free riders, benefiting from the efforts of a few without contributing themselves. (The same issue faced farmers Smith and Jones in the fence-mending problem described earlier.) It is this prospect of free riding that risks undermining collective action. Leadership structures are thus put in place to enforce punishments meant to discourage individuals from reneging on the individual contributions required to enable the group to pursue its common goals.

Another way to think about this is to describe a commonly shared goal—say, the mosquito-free meadow—as a public good. A public good is a benefit that others cannot be denied from enjoying once it has been provided. Once the meadow is mosquito-free, it will constitute a benefit to all members of the group, even those who have not contributed to its provision. More generally, a public good is one that can be “consumed” by all individuals, with no exclusions, and that will not run out as people continue to use it. A classic example is a lighthouse. Once erected, it aids all ships, and there is no simple way to charge a ship for using it. Likewise, national defense protects taxpayers and tax avoiders alike. Another example is clean air. Once enough people restrict the pollutants they emit into the air, the cleaner air may be enjoyed even by those who have not restricted their own pollution. Because public goods have these properties, it is easy for some members of a group to free ride on others’ efforts or sacrifices. And as a result, it may be difficult to get anyone to provide public goods in the first place. Collective action is required, so leaders (or governments) with the capacity to induce all group members to contribute often need to get involved.

One of the most notorious collective action problems involves too much of a good thing. Known as the tragedy of the commons, this type of problem reveals how unbridled self-interest can have damaging collective consequences. A political party’s reputation, for example, can be seen as something that benefits all politicians affiliated with the party. This collective reputation is not irreparably harmed if one legislator takes advantage of the party’s reputation to secure a minor amendment helpful to a special interest in her district. But if lots of party members do it, the party comes to be known as the champion of special interests, and its reputation is tarnished. A pool of resources is not much depleted if someone takes a little of it, but it is if lots of people take from it—a forest is lost one pine tree at a time; the atmosphere is polluted one particle at a time. The party’s reputation, the forest, and the atmosphere are all commons.14 The problem to which they are vulnerable is overgrazing: when a common resource is irreparably depleted by individual actions.15

To summarize, individuals try to accomplish goals not only as individuals but also as members of larger collectives (families, associations, political parties) and even larger categories (economic classes, ethnic groups, nationalities). The rationality principle (all political behavior has a purpose) accounts for individual initiative. The collective action principle describes the paradoxes encountered, the obstacles to be overcome, and the incentives necessary when individuals attempt to coordinate their energies, accomplish collective purposes, and secure the dividends of cooperation. Much of politics is about doing this or failing to do this. The institution principle provides a logical solution to these problems of collective action: collective activities that are both important and frequently occurring are regularized in the form of institutions. Institutions do the public’s business while relieving communities of the need to reinvent collective action each time it is required. Thus, we have a rationale for government.

The Policy Principle: Political Outcomes Are the Products of Individual Preferences, Institutional Procedures, and Collective Action

Ultimately, we are interested in the results of politics—the collective decisions that emerge from the political process. A Nebraska farmer, for example, cares about how public laws affect her welfare and that of her family, friends, and neighbors. She cares about how export policies affect the prices her crops can earn in international markets and how monetary policy influences the cost of seed and fertilizer; about the funding of research and development efforts in agriculture; and about the affordability of the state university where she hopes to educate her children. She also will care, eventually, about inheritance laws and their effect on her ability to pass her farm on to her kids without the government taking much of it in estate taxes. As students of American politics, we need to consider the links that individual goals, institutional arrangements, and collective action have with policy outcomes. How do all of these leave their marks on policy? What biases and tendencies manifest themselves in public decisions?

The linchpin connecting individuals and institutions with policy is the various motivations of political actors. As we saw in our discussion of the rationality principle, their ambitions—ideological, personal, electoral, and institutional—provide incentives to craft policies in particular ways. In fact, most policies make sense only as reflections of individual politicians’ interests, goals, and beliefs. Examples include:

Personal interests:Congressman X is an enthusiastic supporter of government subsidies for home heating oil, but he opposes regulation to keep its price down because some of his friends own heating-oil distributorships.16

Electoral ambitions:Senator Y, a well-known political moderate, has lately been introducing very conservative amendments to bills dealing with the economy in an effort to appeal to conservatives who might donate to their budding presidential campaign.

Institutional ambitions:Representative Z has given a rousing speech on the House floor in support of an amendment that is near and dear to their party leader. They hope their support for the amendment will earn them an endorsement for an assignment to the prestigious Appropriations Committee.

These examples illustrate how policies are a product of both institutional procedures and individual aspirations. The procedures are essentially a series of chutes and ladders that shape, channel, filter, and prune the alternatives from which policy choices are ultimately made. The politicians who populate these institutions are driven both by private objectives and by public purposes, pursuing their private interests while working on behalf of the public interest, as they see it.

Because the institutional features of the American political system are complex and policy change requires success at every step, change is often impossibly difficult. Thus, the status quo usually prevails. A long list of players must be satisfied with any given change, or it won’t happen. Most of these politicians will need some form of “compensation” to provide their endorsement and support. For instance, in order to build majority support for a bill, the legislator who drafts the bill must include provisions that benefit other members of the legislature, thereby ensuring that a sufficient number of colleagues will vote in support of it. Derisively, this is called pork-barrel legislation. In fact, most pork-barrel projects can be justified as valuable additions to the public good. What may be pork to the critic may be actual bridges, roads, and post offices for people living in the legislators’ districts.

Elaborate institutional arrangements, complicated policy processes, and intricate political motivations make for a highly combustible mixture. The policies that emerge may be lacking in the neatness that citizens desire, but they are sloppy and slapdash for a reason: the tendency to spread benefits broadly results when political ambition comes up against a decentralized political system.

The History Principle: How We Got Here Matters

One final aspect of our analysis is important: we must ask how we have gotten where we are. How did we get the institutions and policies that are in place today? By what series of steps? When did they arise by choice and when by accident? Every question and problem we confront has a history. History will not tell the same story for every institution, but without it we have neither a sense of how institutions developed and evolved nor a full sense of how they are related to one another. In explaining why governments do what they do, we must turn to history to see what choices were available to political actors at a given time, what consequences resulted, and what consequences might have flowed had different paths been chosen.

Imagine a tree growing from the bottom of the page. Its trunk grows upward from a root ball at the bottom, dividing into branches that continue upward, further dividing into smaller branches. Imagine a path through this tree, from its bottommost roots to the tip of one of the highest branches at the top of the page. There are many such paths, from the one point at the bottom to any of the points at the top. If this were a time diagram, the root ball would represent some beginning point and all of the branch endings would represent the present. Each path is now a possible history. Alternative histories entail irreversibilities: once one starts down a historical path, one cannot always retrace one’s steps.17 Some futures are foreclosed by the choices people have already made or, if not literally foreclosed, then made extremely unlikely.

In this sense we can explain a current situation at least in part by describing the historical path that led to it. Certain scholars use the term path dependency to suggest that some possibilities are more or less likely because of earlier events and choices. Both the status quo and the paths that diverge from it significantly delimit future possibilities. For example, in the early 1990s, President Bill Clinton formulated the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy for the treatment of gay men and women in the military: the military could not ask about a soldier’s sexual orientation, and gay troops could serve so long as they did not reveal their sexual orientation. This move made it virtually impossible to return to the old status quo in which gay men and women could not serve at all. However, the policy chosen by the Clinton administration also made it difficult to progress to a more enlightened policy in which troops were not prevented from expressing their identity. This change did not happen for two decades because Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell dissuaded members of the military from advocating for a new policy in ways that might have exposed their sexual orientation.

Three factors help explain why history often matters in political life: rules and procedures, loyalties and alliances, and historically conditioned points of view. As for rules and procedures, choices made during one point in time continue to have consequences for years, decades, or even centuries. For example, the United States’ single-member-district, plurality voting rules, established in the eighteenth century, continue to shape the nation’s party system today.18 Those voting rules, as we will see in Chapter 12, help explain why the United States has a two-party system rather than a multiparty system, as is found in many other Western democracies. Thus, a set of choices made more than 200 years ago affects party politics today.

History also often matters in terms of political loyalties and alliances. Many of the most important political alliances in the United States today are products of events from decades ago. For example, Jewish voters are among the Democratic Party’s most loyal supporters, consistently giving 80 to 90 percent of their votes to Democratic presidential candidates. Yet on the basis of economic interest, Jewish people, a generally middle- and upper-middle-class social group, might be expected to vote for Republicans. Moreover, recently the GOP has been a strong supporter of Israel. Why, then, do Jewish voters overwhelmingly support Democrats? Part of the answer has to do with history. The Jewish community, historically, has suffered discrimination in the United States. In the 1930s, the Democratic Party under Franklin Delano Roosevelt became one vehicle through which Jewish people in America began to enjoy greater economic opportunity. This historical experience continues to shape Jewish political identity. Similar historical experiences underlie the political loyalties of African Americans to the Democrats and some Cuban Americans to the Republicans.

A third factor explaining why history matters is that past events shape current perspectives. For example, many Americans in their late 60s and 70s viewed the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan through the lens of their experience with the Vietnam War, expecting U.S. military involvement in a developing country to lead to a quagmire of costs and casualties. But at the time of the Vietnam War, many older Americans viewed the events in Vietnam through the lens of the 1930s, when Western democracies were slow to resist Adolf Hitler’s Germany. These people saw a failure to respond strongly to aggression as a form of appeasement that would only encourage hostile powers to use force against U.S. interests. Thus, at any given time, people’s perspectives are shaped by what they have learned from their own histories.

Glossary

- instrumental

- Done with purpose, sometimes with forethought, and even with calculation.

- institutions

- A set of formal rules and procedures, often administered by a bureaucracy, that shapes politics and governance.

- jurisdiction

- The domain over which an institution or member of an institution has authority.

- agenda power

- The control over what a group will consider for discussion.

- veto power

- The ability to defeat something even if it has made it on to the agenda of an institution.

- decisiveness rules

- A specification of when a vote may be taken, the sequence in which votes on amendments occur, and how many supporters determine whether a motion passes or fails.

- delegation

- The transmission of authority to some other official or body (though often with the right of review and revision).

- principal-agent relationship

- The relationship between a principal (such as a citizen) and an agent (such as an elected official), in which the agent is expected to act on the principal’s behalf.

- transaction costs

- The cost of clarifying each aspect of a principal-agent relationship and monitoring it to make sure both parties comply with all arrangements.

- collective action

- The pooling of resources and the coordination of effort and activity by a group of people (often a large one) to achieve common goals.

- free riding

- Enjoying the benefits of some good or action while letting others bear the costs.

- public good

- A good that (1) may be enjoyed by anyone if it is provided and (2) may not be denied to anyone once it has been provided. Also called collective good.

- tragedy of the commons

- The idea that a common resource, available to everyone, will more likely than not be abused or overused.

- path dependency

- The idea that certain possibilities are made more or less likely because of historical events and decisions—because of the historical path taken.

Endnotes

- The classic statement of this premise is David R. Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974). Although nearly five decades old, this book remains a source of insight and wisdom.Return to reference 4

- The classic statement of this premise is Richard F. Fenno, Congressmen in Committees (Boston: Little, Brown, 1973), another book that remains relevant decades after its publication.Return to reference 5

- As Vince Lombardi, the famous coach of the Green Bay Packers football team, once said, “Winning isn’t everything; it’s the only thing.”Return to reference 6

-

Most political actors are motivated by self-interest. The motivations of judges and justices, however, have proved more difficult to ascertain because their lifetime appointments free them from looking ahead to the next election or occasion for “contract renewal.” For an interesting discussion of judicial motivations by an eminent law professor and former judge, see Richard A. Posner, “What Do Judges and Justices Maximize? (The Same Thing Everybody Else Does),” Supreme Court Economic Review 3 (1993): 1–41.Return to reference 7

- It was only in August 2016, for example, that the FDA acquired the authority to regulate tobacco products.Return to reference 8

- For a general discussion of motions to close debate and get on with the decision, see Henry M. Robert, Robert’s Rules of Order (1876), items III.21 and VI.38. Robert’s Rules has achieved icon status and now exists in an enormous variety of forms. For a more current version, the 1915 edition can be found here: www.bartleby.com/176/.Return to reference 9

- Thus, elected officials are simultaneously agents of their constituents and principals for bureaucrats to whom they delegate the authority to implement policy. See Sean Gailmard and John W. Patty, Learning while Governing: Expertise and Accountability in the Executive Branch (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).Return to reference 10

- In the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, the Tammany Hall political organization ran New York City’s Democratic Party like a machine.Return to reference 11

- For a wonderful description of how ranchers in Shasta County, California, organized their social lives and collective interactions in just this fashion, see Robert C. Ellickson, Order without Law: How Neighbors Settle Disputes (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1991).Return to reference 12

- In another context, it is known as the prisoner’s dilemma. We will encounter it again in Chapter 13 when we discuss interest groups.Return to reference 13

-

The original meaning of commons is a shared pasture on which many people graze their cows, to the point of damaging the land. A most insightful discussion of “commons problems,” of which these are examples, is Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990).Return to reference 14

- The classic statement is Garrett Hardin, “The Tragedy of the Commons,” Science 162, no. 3859 (1968): 1243–48.Return to reference 15

- The congressmember’s friends may benefit from a government subsidy if it reduced the price point of the oil, making it accessible to more customers, but they would not want the price they can charge for the oil to be restricted.Return to reference 16

- With tree climbing this is not literally true, or else once we started climbing a tree, we would never get down! The tree analogy is not perfect here.Return to reference 17

- In political systems with single-member districts, one legislator is selected to represent each district. (Other electoral systems may select multiple members from each district.) A plurality voting rule declares that the one legislator selected to represent a district is the one who earns the most votes (not necessarily a majority of the votes) in an election.Return to reference 18