|

TABLE 3.1 A NEW FEDERAL SYSTEM? THE CASE RECORD, 1995–2019 |

||

|

CASE |

DATE |

COURT HOLDING |

|

United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 |

1995 |

Voids federal law barring handguns near schools: this law is beyond Congress’s power to regulate commerce |

|

Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida, 517 U.S. 44 |

1996 |

Voids federal law giving tribes the right to sue a state in federal court: “sovereign immunity” requires that a state grant permission to be sued |

|

Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 |

1997 |

Voids a key provision of the Brady Bill requiring states to make background checks on gun purchases: as an “unfunded mandate,” it violated state sovereignty under the Tenth Amendment |

|

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 |

1997 |

Restricts Congress’s power under the Fourteenth Amendment to regulate city zoning and health and welfare policies to “remedy” rights: Congress may not expand those rights |

|

Alden v. Maine, 527 U.S. 706 |

1999 |

Declares states “immune” from suits by their own employees for overtime pay under the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 (see also the Seminole case) |

|

United States v. Morrison, 529 U.S. 598 |

2000 |

Extends the Seminole case by invalidating the Violence Against Women Act: states may not be sued by individuals for failing to enforce federal laws |

|

Gonzales v. Oregon, 546 U.S. 243 |

2006 |

Upholds state assisted-suicide law over attorney general’s objection: federal government cannot outlaw a medical practice authorized by a state’s laws |

|

National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. 519 |

2012 |

Upholds the Affordable Care Act and expansion of federal control over health care policy: requiring individuals to purchase health insurance was a permissible exercise of congressional power to levy taxes |

|

Murphy v. NCAA, 584 U.S. ____ |

2018 |

Declares that the federal government cannot tell the states what laws to enact: states cannot be prohibited from allowing sports gambling |

|

Rucho v. Common Cause, 588 U.S. ____ |

2019 |

Declares that the federal courts cannot overturn districting plans drawn up by state legislatures even if these served partisan purposes: lets stand gerrymandering schemes in North Carolina and Maryland |

THE SEPARATION OF POWERS

As we have noted, the separation of powers enables several different federal institutions to influence the nation’s agenda, to affect decisions, and to prevent the other institutions from taking action—dividing agenda, decision, and veto power. The Constitution’s framers saw this arrangement, although cumbersome, as an essential means of protecting liberty.

In his discussion of the separation of powers, James Madison quoted the originator of the idea, the French political thinker Baron de Montesquieu: “There can be no liberty where the legislative and executive powers are united in the same person . . . [or] if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.”43 Using the same reasoning, many of Madison’s contemporaries argued that the Constitution did not create enough separation among the three branches, and Madison had to backtrack to insist that complete separation was not required:

Unless these departments [branches] be so far connected and blended as to give to each a constitutional control over the others, the degree of separation which the maxim requires, as essential to a free government, can never in practice be duly maintained.44

This is the secret of how the United States has made the separation of powers effective: the framers made it self-enforcing by giving each branch of government the means to participate in, and partially or temporarily obstruct, the workings of the other branches.

Checks and Balances: A System of Mutual Vetoes

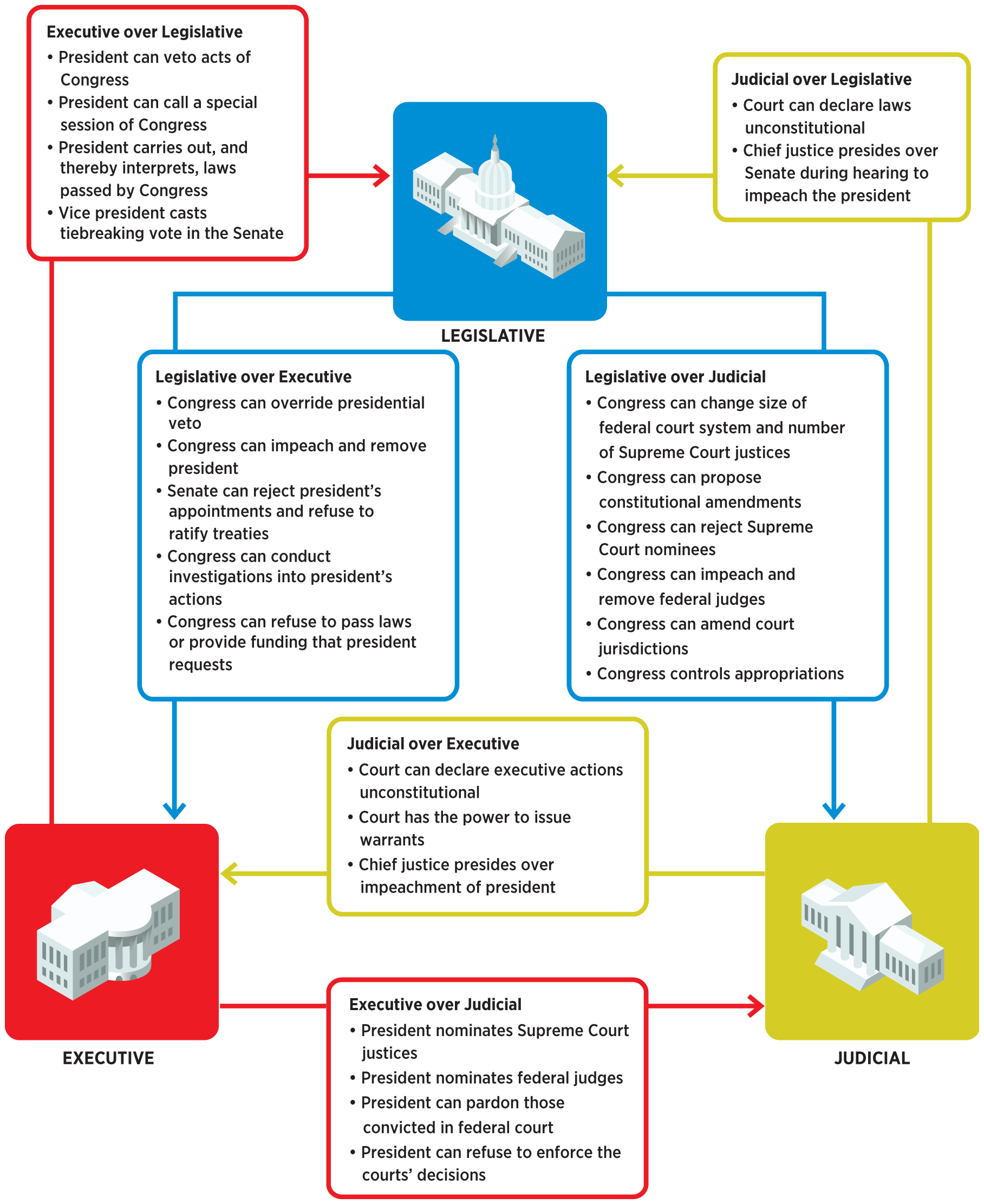

The means by which the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the federal government interact with each other is known informally as checks and balances. This arrangement gives each branch agenda and veto power and requires all the branches to agree on national policies (Figure 3.4). Examples include the presidential power to veto legislation passed by Congress; the power of Congress to override the veto by a two-thirds majority vote; the power of the Senate to approve presidential appointments; the power of the president to appoint Supreme Court justices and other federal judges with Senate approval; and the power of the Court to engage in judicial review (which we discuss later in this chapter). The framers sought to guarantee that the three branches would use the checks and balances as weapons against each other by giving each branch a different political constituency: direct, popular election of the members of the House and indirect election of senators (until the Seventeenth Amendment, adopted in 1913); indirect election of the president (still in effect, at least formally); and appointment of federal judges for life. The best characterization of the separation-of-powers principle in action is “separated institutions sharing power.”45

FIGURE 3.4

CHECKS AND BALANCES

Legislative Supremacy

Within the system of separated powers, the framers provided for legislative supremacy by making Congress the preeminent branch. Legislative supremacy made the provision of checks and balances that the other branches could employ against Congress all the more important.

The framers’ intention of legislative supremacy is evident in their decision to place the provisions for national powers in Article I, the legislative article, and to treat the powers of the national government as powers of Congress. In a system based on the rule of law, the power to make the laws is the supreme power. Article I, Section 8, provides in part that “Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes . . . ; To borrow Money . . . ; To regulate Commerce” (emphasis added). The Founders also provided for legislative supremacy by giving Congress sole power over appropriations, stipulating that all revenue bills must originate in the House of Representatives. Madison recognized legislative supremacy as part and parcel of the separation of powers:

It is not possible to give to each department an equal power of self-defense. In republican government, the legislative authority necessarily predominates. The remedy for this inconveniency is to divide the legislature into different branches; and to render them, by different modes of election and different principles of action, as little connected with each other as the nature of their common functions and their common dependence on the society will admit.46

Essentially, Congress was so likely to dominate the other branches that it would have to be divided against itself, into House and Senate. One could almost say that the Constitution provided for four branches of government, not three.

Although “presidential government” gradually supplanted legislative supremacy after 1937, the relative power position of the executive and legislative branches since that time has varied with the rise and fall of political parties. It has been especially tense during periods of divided government, when one party controls the White House and another controls Congress. For instance, in 2018 when President Trump (a Republican) declared a national emergency along the southern border of the United States and issued executive orders diverting funds from the Department of Defense’s budget to start work on a border wall, Congress reacted sharply. The Democrat-controlled House of Representatives voted to block the president’s emergency declaration, and even some GOP lawmakers sharply criticized the president’s actions.

The Rationality Principle at Work

The framers’ idea that the president and Congress would check and balance each other rests, in part, on an application of the rationality principle. The framers assumed that each branch would seek to maintain or expand its power and would resist “encroachments” by the other branch. This idea seems consistent with the actual behavior of presidents and congressional leaders who have battled over institutional prerogatives since at least the Nixon administration. For example, the Watergate scandal began when President Nixon sought a reorganization of the executive branch that would have increased presidential control and reduced congressional oversight powers.47 After Nixon’s resignation, Congress acted to delimit presidential power, but subsequently President Reagan undid Congress’s efforts and bolstered the White House. During President George W. Bush’s second term, Congress and the president battled constantly over the president’s refusals to disclose information on the basis of executive privilege and his assertions that only the White House was competent to manage the nation’s security. Bush famously stated, “I am the decider.” President Obama faced divided government for the final six years of his administration. In the 2016 elections, Americans chose a Republican president and left the GOP in control of both houses of Congress. This development might have brought about closer cooperation between the executive and legislative branches, but ideological conflicts within the Republican coalition often undermined leaders’ ability to enact major pieces of legislation.

In 2018, the Democrats won control of the House of Representatives and launched a number of investigations into the activities of President Trump and his aides. Trump responded by ordering White House staffers and other officials to refuse to testify before Congress and by asserting executive privilege to deny Congress access to information. This tactic touched off a series of legal battles between the president and Congress. In 2020, the Democratic House of Representatives impeached President Trump, charging him with abuse of power in an effort to coerce Ukraine to investigate Trump’s political rival, former vice president Joseph Biden. After a brief trial, Trump was acquitted by the Republican-controlled Senate.

Over time, the president has generally possessed an advantage in this struggle between institutions. The president is a unitary actor, whereas Congress, as a collective decision maker, suffers from collective action problems (see Chapter 6). That is, each member may have individual interests that are inconsistent with the collective interests of Congress as a whole. For example, though Congress initially supported Bush’s plan to use force in Iraq in 2003, members were uneasy about his assertion that he did not need congressional approval to do so. The president used the war to underline claims of institutional power, but few members of Congress thought it politically safe to express their concerns about presidential overreach when the public was clamoring for action. These considerations help explain why, over time, the powers of the presidency have grown and those of Congress have diminished.48 We will return to this topic in Chapter 7.

The Role of the Supreme Court: Establishing Decision Rules

The role of the judicial branch in the separation of powers has depended on the power of judicial review (see Chapter 9), a power not provided for in the Constitution but asserted by Chief Justice Marshall in 1803:

If a law be in opposition to the Constitution; if both the law and the Constitution apply to a particular case, so that the Court must either decide that case conformable to the law, disregarding the Constitution, or conformable to the Constitution, disregarding the law; the Court must determine which of these conflicting rules governs the case: This is of the very essence of judicial duty.49

Marshall’s decision was an extremely important assertion of judicial power: in effect, he declared that whenever there was doubt or disagreement about which rule should apply in a particular case, the Court would decide. In this way, Marshall made the Court the arbiter of all future debates between Congress and the president and between the federal and state governments.

Judicial review of the constitutionality of acts of the president or Congress is relatively rare. For example, there were no Supreme Court reviews of congressional acts in the 50-plus years between Marbury v. Madison (1803) and Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). In the century or so between the Civil War and 1970, 84 acts of Congress were held unconstitutional (in whole or in part), but there were long periods of complete Court deference to Congress, punctuated by flurries of judicial review during times of social upheaval. The most significant was in 1935–36, when the Court invalidated 12 acts of Congress, blocking virtually the entire New Deal program.50 Thereafter the Court did not void any significant acts until 1983, when it declared unconstitutional the legislative veto, a practice in which Congress would authorize the president to take certain kinds of actions while reserving the right to override particular actions with which it disagreed.51 The Court became much more activist (that is, less deferential to Congress) after the appointment of Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist in 1986.52 Each of the cases in Table 3.1 altered some aspect of federalism by declaring unconstitutional all or an important portion of an act of Congress.

Since the New Deal period, the Court has been far more deferential toward the president, though there have been several significant confrontations. The first was the so-called steel seizure case of 1952, in which the Court refused to permit President Harry Truman to use “emergency powers” to take control of the country’s steel mills during the Korean War.53 In a second case, the Court rejected President Nixon’s claim that he was not required to turn over subpoenaed tape recordings relevant to the Watergate investigation. The Court argued that, although executive privilege protected the confidentiality of communications to and from the president, this protection did not extend to data in presidential files or tapes linked to criminal prosecutions.54 In a third instance, the Court struck down the Line Item Veto Act of 1996, which allowed the president to veto specific items in spending and tax bills without vetoing the entire bill. The Court held that any such change in the procedures of adopting laws would have to be made by amendment to the Constitution, not by legislation.55

A fourth important confrontation came a few years after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. In 2004, the Court held that the estimated 650 “enemy combatants” detained without formal charges at the U.S. naval station at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, had the right to seek release through a writ of habeas corpus.56 Congress answered this decision with the Military Commissions Act (2006), which included a provision declaring that enemy combatants held at Guantánamo Bay could not avail themselves of the right of habeas corpus. Then, in 2008, the Supreme Court responded by striking down the offending provision and affirming that the Guantánamo detainees had the right to challenge their detentions in federal court.57 The Court noted that habeas corpus was among the most fundamental of constitutional rights and was included in the Constitution even before the Bill of Rights was added.

During the Trump era, a number of federal district and circuit courts ruled against the president, particularly on immigration issues. The Supreme Court, however, generally refrained from directly confronting the president. The closest it has come involved the matter of whether a question asking respondents about their citizenship status could be added to the 2020 census. Critics charged that the question was designed to reduce legislative representation for and federal funding to states with large numbers of undocumented immigrants. Lower federal courts ruled that the question should not be included in the census questionnaire, and the Supreme Court refused to make a final determination, instead sending the matter back to the lower courts for further adjudication.58

In an important case decided during the early months of the Biden administration, the Court again avoided a confrontation with the president by refraining from ruling on the constitutionality of the Affordable Care Act.59 An adverse decision would have touched off a firestorm and renewed demands from Democratic progressives that the Court be enlarged to add more Democratic justices. This issue will be more fully discussed in Chapter 9.

Glossary

- legislative supremacy

- The preeminent position within the national government that the Constitution assigns to Congress.

- divided government

- The condition in American government in which one party controls the presidency, while the opposing party controls one or both houses of Congress.

- executive privilege

- The claim that confidential communications between a president and close advisers should not be revealed without the president’s consent.

- writ of habeas corpus

- A court order demanding that an individual in custody be brought into court and shown the cause for detention; habeas corpus is guaranteed by the Constitution and can be suspended only in cases of rebellion or invasion.

Endnotes

- Rossiter, Federalist Papers, no. 47 (James Madison), p. 302.Return to reference 43

- Rossiter, Federalist Papers, no. 48 (James Madison), p. 308.Return to reference 44

- Richard E. Neustadt, Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan (New York: Free Press, 1990), p. 33.Return to reference 45

- Rossiter, Federalist Papers, no. 51 (James Madison), p. 322.Return to reference 46

- Benjamin Ginsberg and Martin Shefter, Politics by Other Means: Politicians, Prosecutors, and the Press from Watergate to Whitewater, 3rd ed. (New York: Norton, 2002), chap. 1.Return to reference 47

- Benjamin Ginsberg, Presidential Government (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016).Return to reference 48

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803).Return to reference 49

-

The Supreme Court struck down 8 out of 10 New Deal statutes. For example, in Panama Refining Company v. Ryan, 293 U.S. 388 (1935), the Court ruled that a section of the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 was an invalid delegation of legislative power to the executive branch. And in A. L. A. Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935), the Court found the National Industrial Recovery Act itself to be invalid for the same reason.Return to reference 50

- Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983).Return to reference 51

- Cass R. Sunstein, “Taking Over the Courts,” New York Times, November 9, 2002, p. A19.Return to reference 52

- Youngstown Sheet and Tube Company v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952).Return to reference 53

- United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683 (1974).Return to reference 54

- Clinton v. City of New York, 524 U.S. 417 (1998).Return to reference 55

- Rasul v. Bush, 542 U.S. 466 (2004).Return to reference 56

- Boumediene v. Bush, 553 U.S. 723 (2008).Return to reference 57

- Department of Commerce v. New York, 588 U.S. ____ (2019).Return to reference 58

- California v. Texas, 19-840, 2021.Return to reference 59