Origins: An Introduction

what if . . .

what if . . .

What if Earth formed 4 billion years after the Big Bang, rather than 9.3 billion years after it: How might Earth be different?

How and when did the universe begin? What combination of events led to the existence of humans as sentient beings living on a small, rocky planet orbiting a typical middle-aged star? Are others like us scattered throughout the galaxy?

In these “Origins” sections, which conclude each chapter, we look into the origin of the universe and the origin of life on Earth. We also examine the possibilities of life elsewhere in the Solar System and beyond—a subject called astrobiology. This origins theme includes the discovery of planets around other stars and how they compare with the planets of our own Solar System.

Later in the book, we present observational evidence that supports the Big Bang theory, which states that the universe started expanding from an infinitesimal size about 13.8 billion years ago. In the early universe, only the lightest chemical elements were found in substantial amounts: hydrogen and helium, and tiny amounts of lithium and beryllium. However, we live on a planet with a central core consisting mostly of heavy elements such as iron and nickel, surrounded by outer layers made up of rocks containing large amounts of silicon and various other elements—all heavier than the original elements. The human body contains carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, calcium, phosphorus, and a host of other chemical elements—all of which are heavier than hydrogen and helium. If those heavier elements that make up Earth and our bodies were not present in the early universe, then where did they come from?

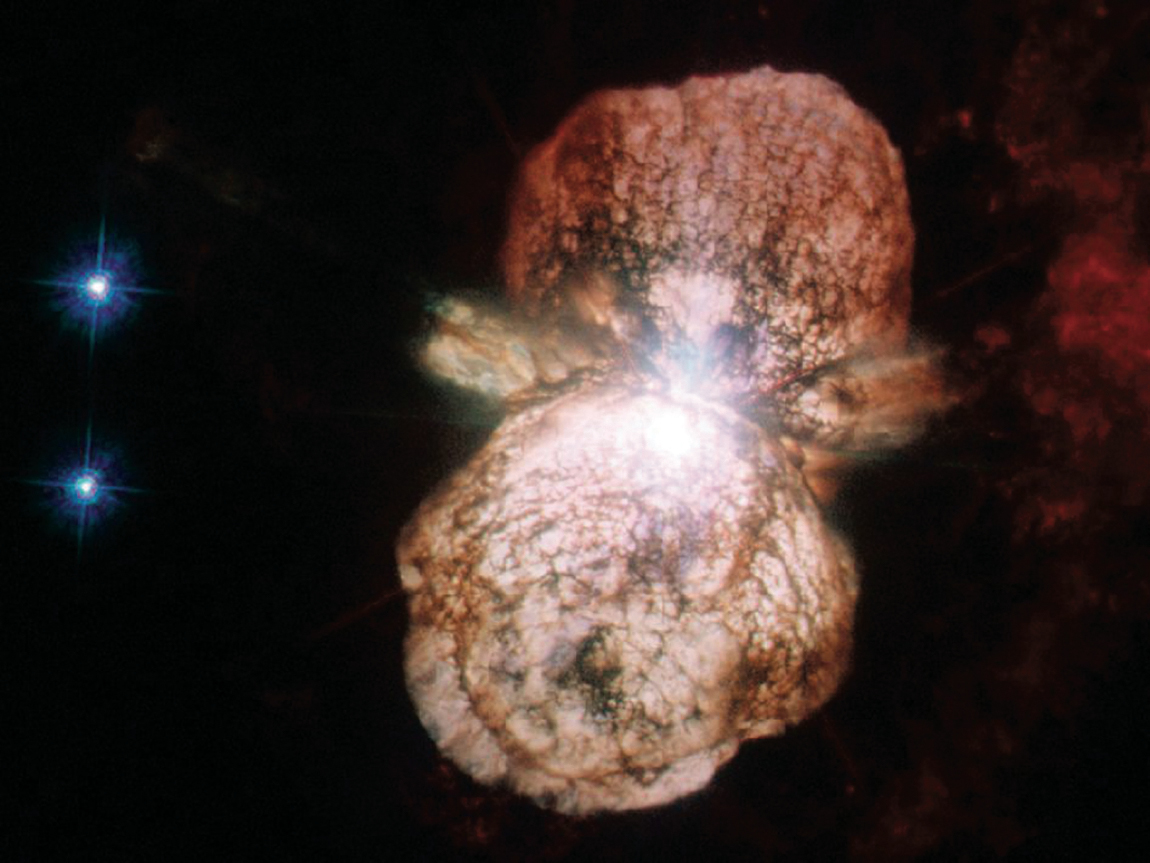

The answer to that question lies within the stars themselves (Figure 1.8). Earlier “generations” of stars supplied the building blocks for the chemical processes that we see in the universe, including life. In the core of a star, light elements, such as hydrogen, combine to form more massive atoms, which eventually leads to atoms such as carbon. When a star nears the end of its life, it often loses much of its material—including some of the new atoms formed in its interior—by ejecting it back into interstellar space. That material combines with material lost from other stars—some of which produced even more massive atoms as they exploded—to form large clouds of dust and gas. Those clouds go on to make new stars and planets, similar to our Sun and Solar System. The phrase “we are stardust” is not just poetry; we are literally made of recycled stardust.

unanswered questions

Does life as we know it exist elsewhere in the universe? At the time of this writing, no scientific evidence indicates that life exists on any other planet.

Studying origins also provides examples of the process of science. Many physical processes in chemistry, planetary science, physics, and astronomy that are seen on Earth or in the Solar System are observed across the Milky Way and throughout the universe. As of this writing, though, the only biology we know about is that which exists on Earth. At this point in human history, then, much of what scientists can say about the origin of life on Earth and the possibility of life elsewhere is reasoned extrapolation and educated speculation. In these “Origins” sections, we address some of those hypotheses and try to be clear about which are speculative and which have been tested.

Glossary

- astrobiology

- An interdisciplinary science combining astronomy, biology, chemistry, geology, and physics to study life in the cosmos.

- Big Bang

- The event that occurred 13.8 billion years ago that marks the beginning of time and the universe.