Astronomy in Action: The Cause of Earth’s Seasons

2.2 Revolution about the Sun Leads to Changes during the Year

Earth orbits (or revolves) around the Sun in the same direction that Earth spins about its axis—counterclockwise as viewed from above Earth’s North Pole (see Figure 2.2). A year is defined as the time Earth takes to complete one revolution around the Sun—it’s a little bit less than 365.25 days. Earth’s motion around the Sun is responsible for many of the patterns of change we see in the sky and on Earth, including changes in the stars we see overhead. Because of that motion, the stars in the night sky change throughout the year, and Earth experiences seasons.

Constellations and the Zodiac

About 9000 stars are visible to the naked eye—spread out across the sky. As Earth orbits the Sun, our view of these stars changes. To follow the patterns of the Sun and the stars, early humans grouped together stars that formed recognizable patterns, called constellations. People from different cultures saw different patterns and projected ideas from their own cultures onto what they saw in the sky. Constellations are creations of the human imagination.

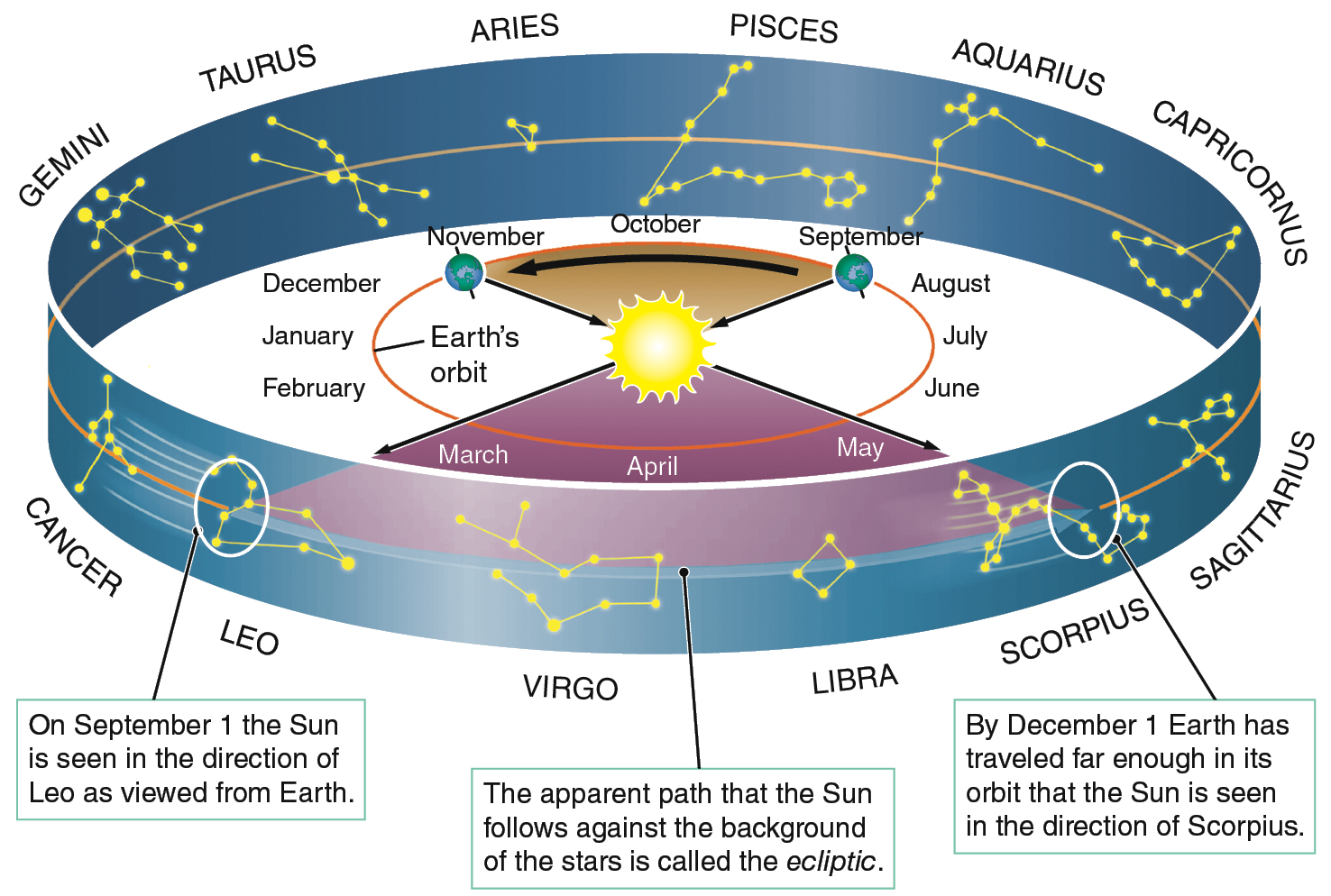

If you noted the position of the Sun in relation to the stars each day for a year, you would find that the Sun traces out a great circle against the background of the stars (Figure 2.13). On September 1, the Sun appears to be in the direction of the constellation Leo. Six months later, on March 1, Earth is on the other side of the Sun, and the Sun appears from our perspective on Earth to be in the direction of the constellation Aquarius. Recall that the Sun’s apparent path against the background of the stars is called the ecliptic (the blue band in Figure 2.13). The constellations that lie along the ecliptic through which the Sun appears to move are called the constellations of the zodiac.

Today, astronomers use an officially sanctioned set of 88 constellations to serve as a road map of the sky. Constellations visible from the Northern Hemisphere draw their names primarily from the list of constellations that the Alexandrian astronomer Ptolemy compiled 2000 years ago. Constellation names in the Southern Hemisphere come from European explorers who visited the Southern Hemisphere during the 17th and 18th centuries. Every star in the sky lies within the borders of a single constellation. This makes it possible to catalog all the stars using the names of their parent constellation. Following the Greek alphabet, astronomers call the brightest star in a constellation alpha; the second brightest, beta; and so forth. For example, Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, lies within the constellation Canis Major (meaning “big dog”). So Sirius is also called “Alpha Canis Majoris,” indicating that it is the brightest star in Canis Major. Appendix 7 includes sky maps showing the constellations.

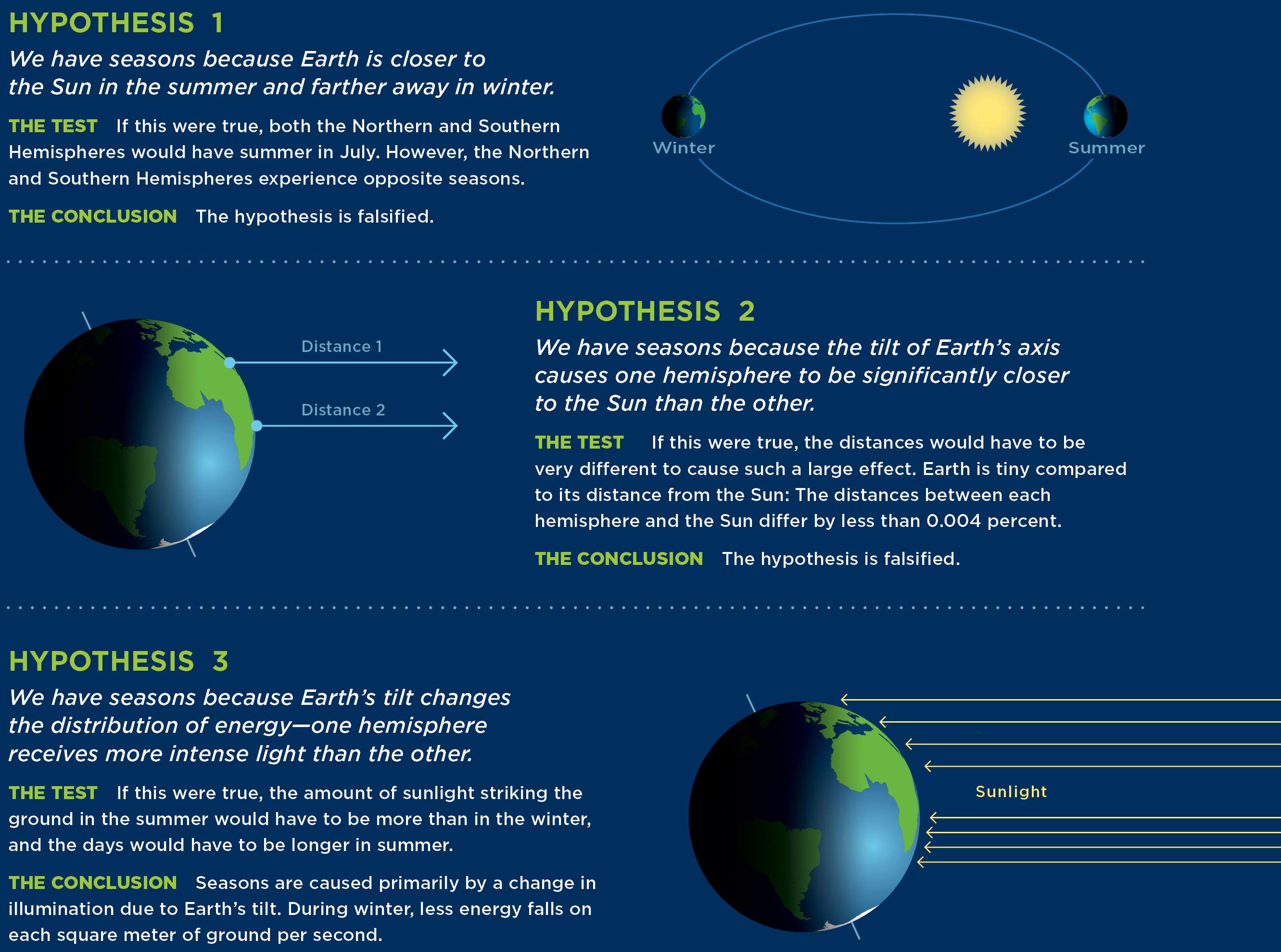

Earth’s Axial Tilt and the Seasons

To understand why the seasons change, we need to consider the combined effects of Earth’s rotation on its axis and its revolution around the Sun. Many people believe that seasons change because Earth is closer to the Sun in summer and farther away in winter. How can we test that hypothesis? We might predict: if the distance between Earth and the Sun caused the seasons, then all of Earth should experience summer at the same time of year. But the United States has summer in June, whereas Australia has summer in December. In modern times, we can directly measure the distance between Earth and the Sun, and we find that Earth is actually closest to the Sun at the beginning of January, by about 5 million km. Yet, in the Northern Hemisphere, we have winter in January. We have just falsified the hypothesis tying seasonal change to distance in two ways, so we need to look for a different explanation that accounts for all the available facts.

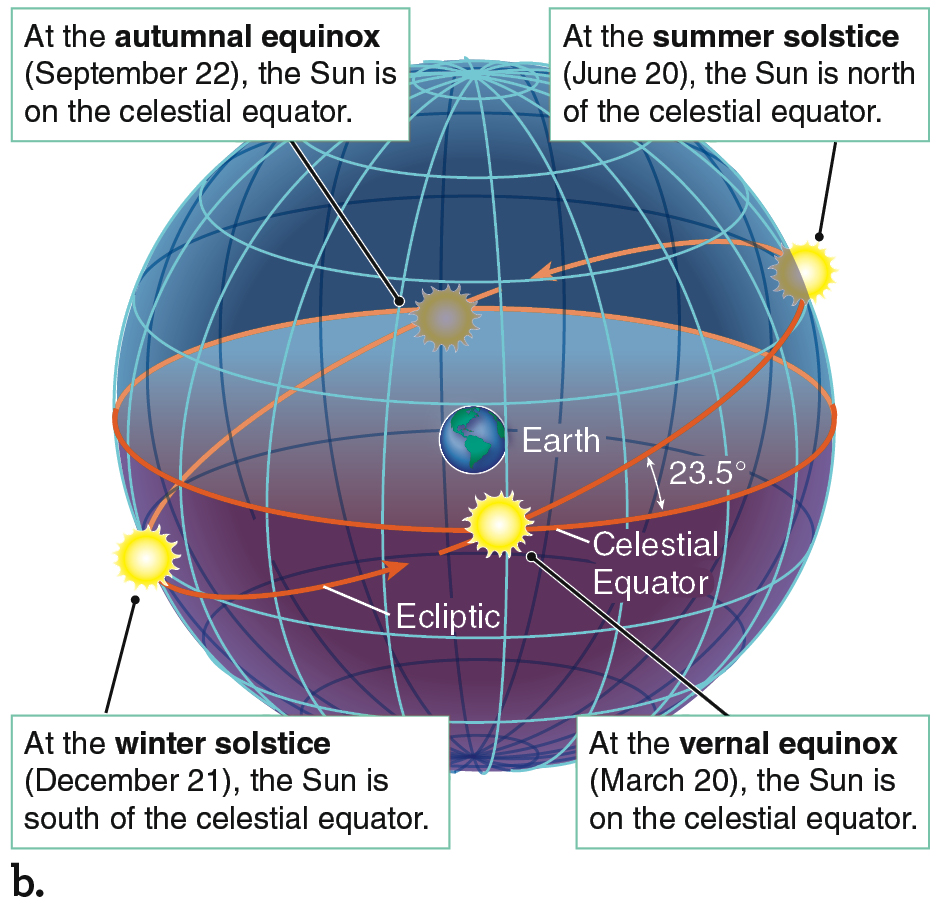

Earthbound observers can see that as the year passes, the Sun is above the horizon longer in summer than in winter. We often say “the days are longer in the summer”, meaning there are more daytime hours, and fewer nighttime ones. The Sun is also higher in the sky as it crosses the meridian in summer than in winter. Observing more closely, the Earthbound observer finds that the Sun appears to move along the ecliptic, which is tilted 23.5° with respect to the celestial equator.

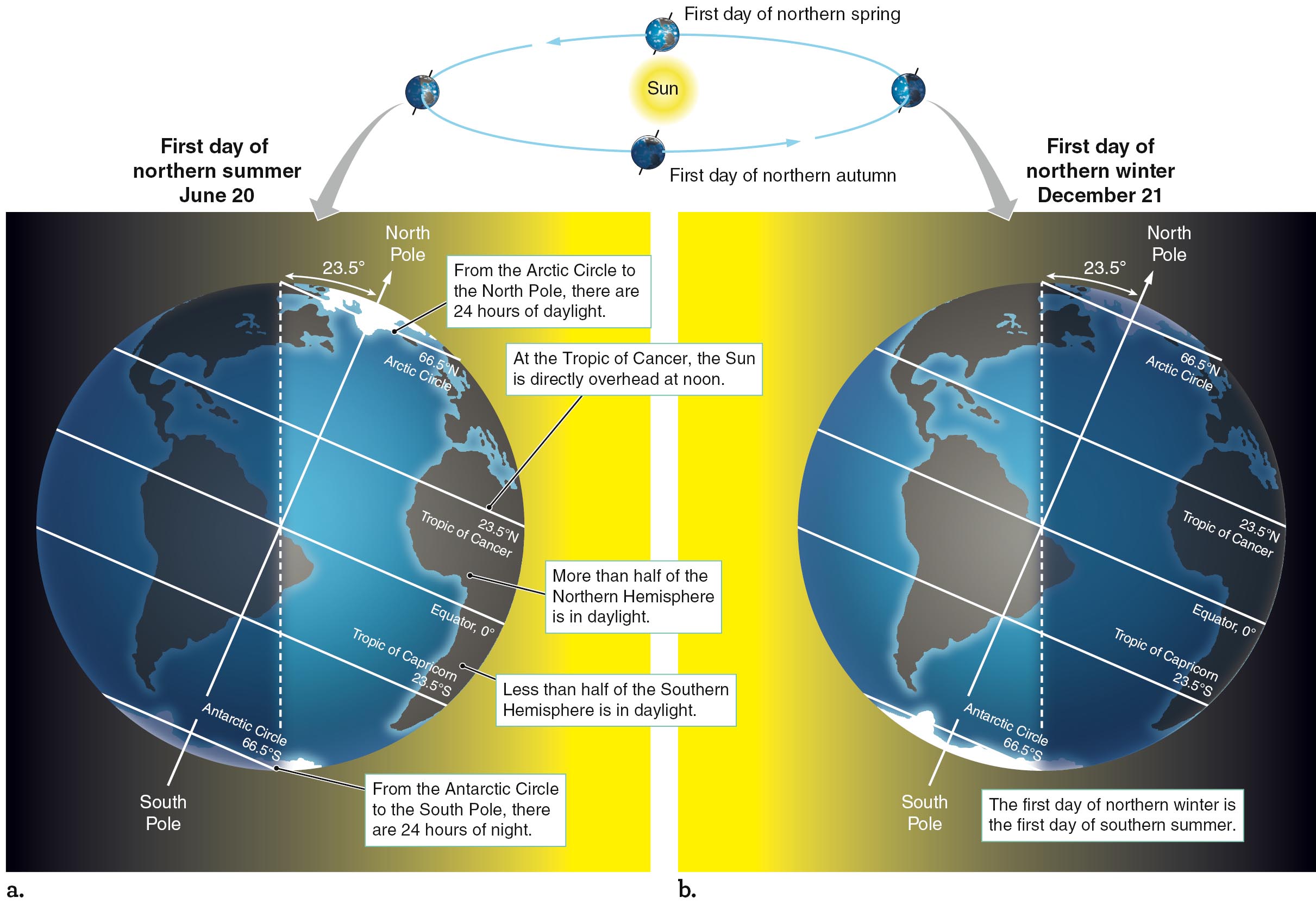

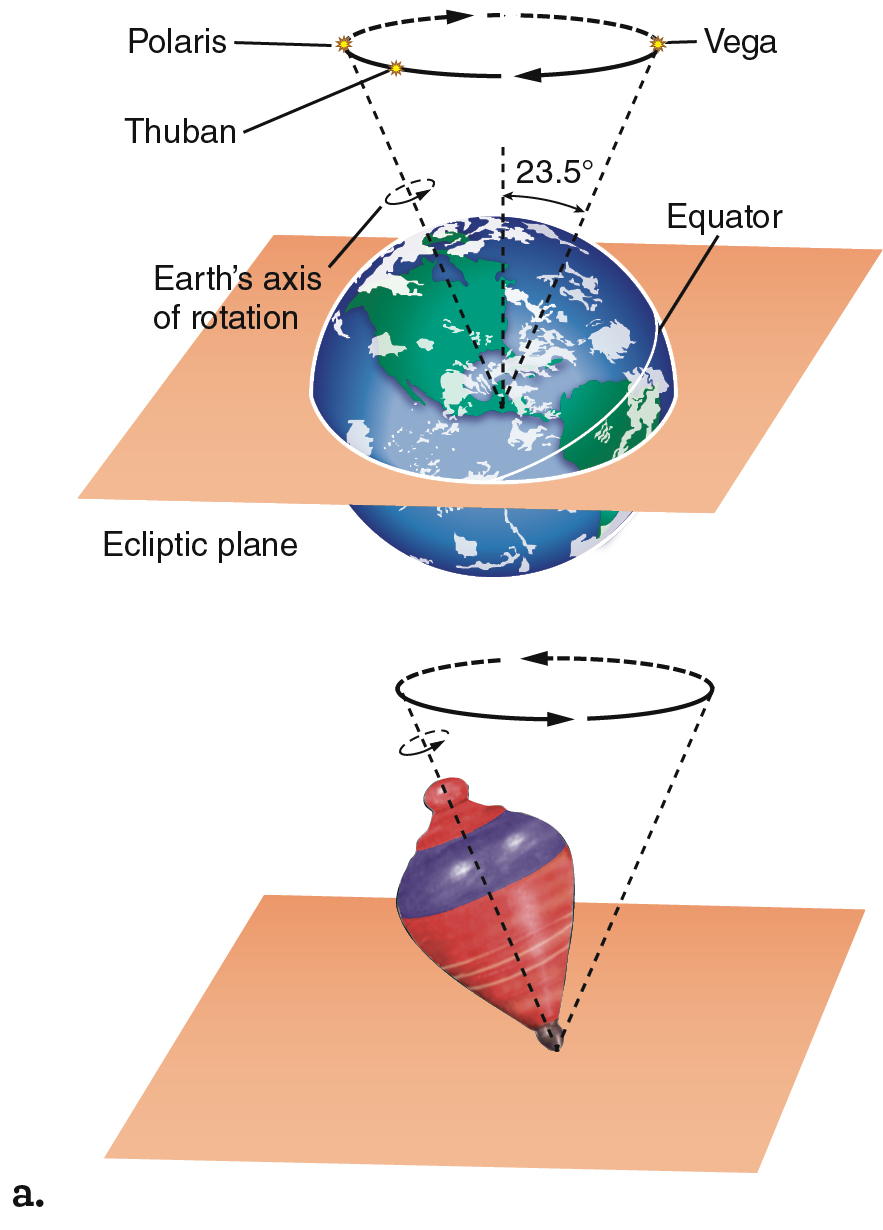

Looking at Earth from space, Figure 2.14 shows that as Earth moves around the Sun over the course of the year, its rotation axis always points in the same direction, toward distant Polaris. This axis is tilted 23.5° from the perpendicular to Earth’s orbital plane, causing the ecliptic to likewise be tilted 23.5° from the celestial equator. As it orbits, Earth is sometimes on one side of the Sun and sometimes on the other. As a result, Earth’s North Pole is sometimes tilted more toward the Sun, and other times the South Pole is tilted more toward the Sun. This accounts for the changing altitude of the Sun as it crosses the meridian, and the changing length of daytime and nighttime. When Earth’s North Pole is tilted toward the Sun, an observer on Earth views the Sun north of the celestial equator. Therefore, for observers in the Northern Hemisphere, the Sun is above the horizon more than 12 hours each day, thus making the daytime longer than 12 hours. Six months later, when Earth’s North Pole is tilted away from the Sun, an observer in the same place views the Sun south of the celestial equator and the daytime is less than 12 hours.

In the preceding paragraph, we specified the Northern Hemisphere because seasons are opposite in the Southern Hemisphere. Look again at Figure 2.14. Around June 20, while the Northern Hemisphere is enjoying the long days and short nights of summer, Earth’s South Pole is tilted away from the Sun. It is winter in the Southern Hemisphere; less than half of the Southern Hemisphere is illuminated by the Sun, and the days are shorter than 12 hours. On December 21, Earth’s South Pole is tilted toward the Sun. It is summer in the Southern Hemisphere, so its days are long and its nights are short.

To understand how the combination of Earth’s axial tilt and its path around the Sun creates seasons, consider what would happen if Earth’s spin axis were exactly perpendicular to the plane of Earth’s orbit (the ecliptic plane). First, the Sun would always be on the celestial equator. Then, at every latitude (except the poles), the Sun would follow the same path through the sky every day, rising due east each morning and setting due west each evening. The Sun would be above the horizon exactly half the time, so days and nights would always be exactly 12 hours long everywhere on Earth. In short, Earth would have no seasons.

what if . . .

where the axial tilt is 25.19°? Considering only this single piece of information, would you expect seasonal variations to be larger, smaller, or about the same as seasonal variations on Earth? Explain.

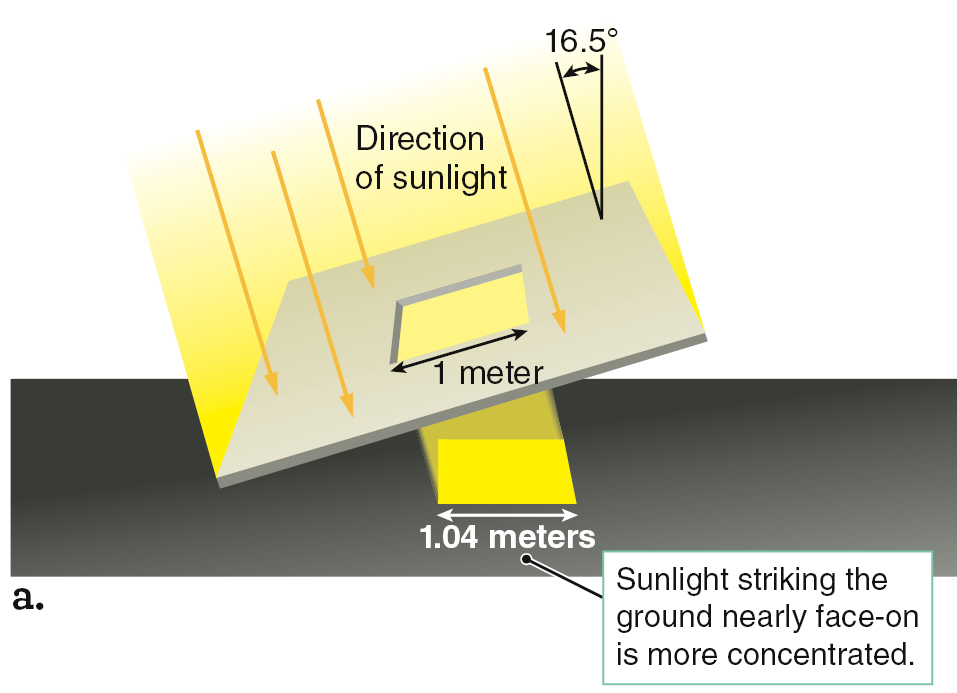

The changing length of days through the year only partly explains seasonal temperature changes. A more important effect relates to the angle at which the Sun’s rays strike Earth. The Sun is higher in the sky during summer than during winter, and sunlight strikes the ground more directly during summer than during winter. To see why that is important, study Figure 2.15. During summer, Earth’s surface is more nearly face-on to the incoming sunlight. The light is concentrated and bright so more energy falls on each square meter of ground each second. During winter, the surface is more tilted with respect to the sunlight, so the light is more diffuse. Less energy falls on each square meter of the ground each second. For example, at latitude 40° north, which stretches across the United States from northern California to New Jersey, more than twice as much solar energy falls on each square meter of ground per second at noon on June 20 as falls there at noon on December 21. That variation is the main reason why summer is hotter and winter is colder.

The Process of Science Figure demonstrates how determining the causes of seasonal change requires accounting for all the known facts. The two effects of Earth’s tilted axis—the directness of sunlight and the different lengths of the night—mean that the Sun heats a hemisphere more at one time of year than another, causing summer and winter.

The Solstices and the Equinoxes

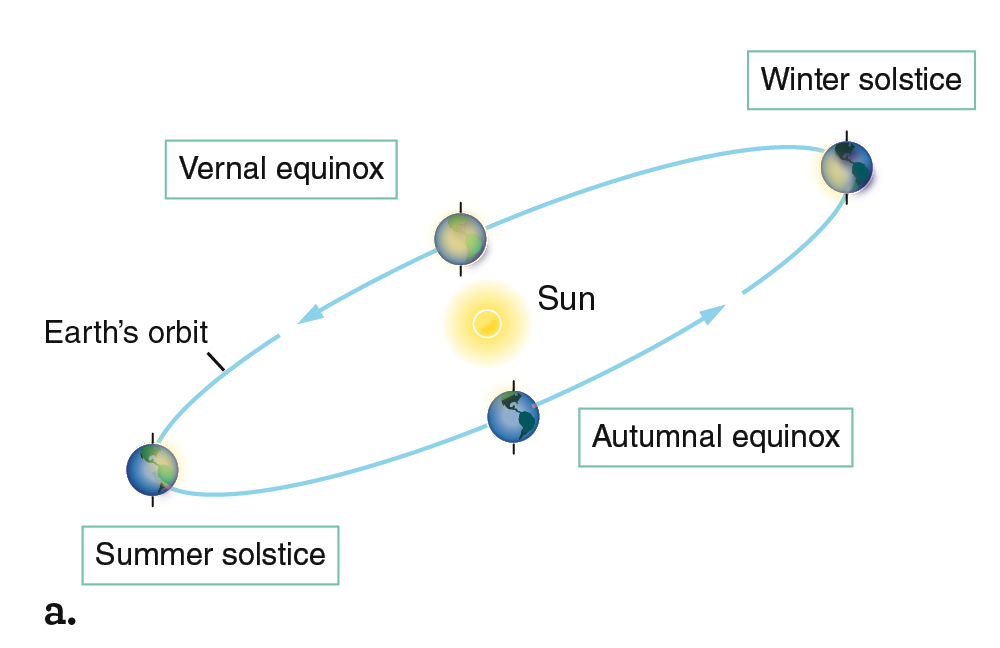

Four days during Earth’s orbit (two solstices and two equinoxes) mark special moments in the year. The day when the Sun is highest in the sky as it crosses the meridian is called the summer solstice. On that day, the Sun rises farthest north of east and sets farthest north of west. In the Northern Hemisphere, that occurs each year near June 20, the first day of summer. Figure 2.14a shows that orientation of Earth and Sun.

Six months after the summer solstice, around December 21, the North Pole is tilted away from the Sun (Figure 2.14b). That day is the winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere—the shortest day of the year and the first day of winter in the Northern Hemisphere. Almost all cultural traditions in the Northern Hemisphere include some sort of major celebration in late December. Those winter festivals celebrate the return of the source of Earth’s light and warmth. The days have stopped growing shorter and are beginning to get longer, and spring will come again.

Between the two solstices, the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator on two days. On those days, the Sun lies directly above Earth’s equator. We call those days equinoxes, which means “equal night,” because the entire Earth experiences 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness. Halfway between summer solstice and winter solstice, the autumnal equinox marks the beginning of fall in the Northern Hemisphere; it occurs around September 22. Halfway between winter solstice and summer solstice, the vernal equinox marks the beginning of spring in the Northern Hemisphere; it occurs around March 20. In the Southern Hemisphere, the dates for the summer and winter solstices, and the autumnal and vernal equinoxes, are reversed from those in the Northern Hemisphere.

PROCESS of SCIENCE Theories Must Fit All the Known Facts

Many people misunderstand the phenomenon of changing seasons because they do not account for all the relevant facts.

New information often challenges misconceptions. Incorporating this new information may alter current theories to improve the explanation of observed phenomena.

Figure 2.16 shows the solstices and equinoxes from two perspectives, oriented so that Earth’s North Pole points straight up. Figure 2.16a is in the reference frame of the Sun. It shows Earth in orbit around a stationary Sun, whereas Figure 2.16b is in the reference frame of Earth. It shows the Sun’s apparent motion along the celestial sphere, around a stationary Earth. Practice shifting between those perspectives. You will know that you understand them when you can look at a position in either panel and predict the corresponding positions of the Sun and Earth in the other panel.

Just as a pot of water on a stove takes time to heat up when the burner is turned on and to cool when the burner is turned off, Earth takes time to respond to changes in heating from the Sun. The hottest months of northern summer are usually July and August, which come after the summer solstice, when days are growing shorter. Similarly, the coldest months of northern winter are usually January and February, which occur after the winter solstice, when days are growing longer. Temperature changes on Earth lag behind changes in the amount of heating we receive from the Sun.

That picture of the seasons must be modified somewhat near Earth’s poles. At latitudes north of 66.5° north and south of 66.5° south, the Sun is circumpolar for a part of the year surrounding the first day of summer. Those lines of latitude are the Arctic Circle and the Antarctic Circle, respectively (see Figure 2.14). When the Sun is circumpolar, it is above the horizon 24 hours per day, earning the polar regions the nickname “land of the midnight Sun” (Figure 2.17). An equally long period surrounds the first day of winter, when the Sun never rises and the nights are 24 hours long. The Sun never rises very high in the Arctic or Antarctic sky, so the sunlight is never very direct. Even with the long days at the height of summer, the Arctic and Antarctic regions remain relatively cool.

In contrast, on the equator, all stars, including the Sun, are above the horizon approximately 12 hours per day. Days and nights there are 12 hours long throughout the year. The Sun passes directly overhead on the first day of spring and the first day of autumn because on those days the Sun is on the celestial equator. Sunlight is most direct, perpendicular to the ground, at the equator on those days. On the summer solstice, the Sun is at its northernmost point along the ecliptic. On that day, and on the winter solstice, the Sun is farthest from the zenith at noon, and therefore sunlight is least direct at the equator.

Latitude 23.5° north is called the Tropic of Cancer, and latitude 23.5° south is called the Tropic of Capricorn (Figure 2.14). The band between those latitudes is called the tropics. If you live in the tropics—in Rio de Janeiro or Honolulu, for example—the Sun will be directly overhead at noon twice during the year.

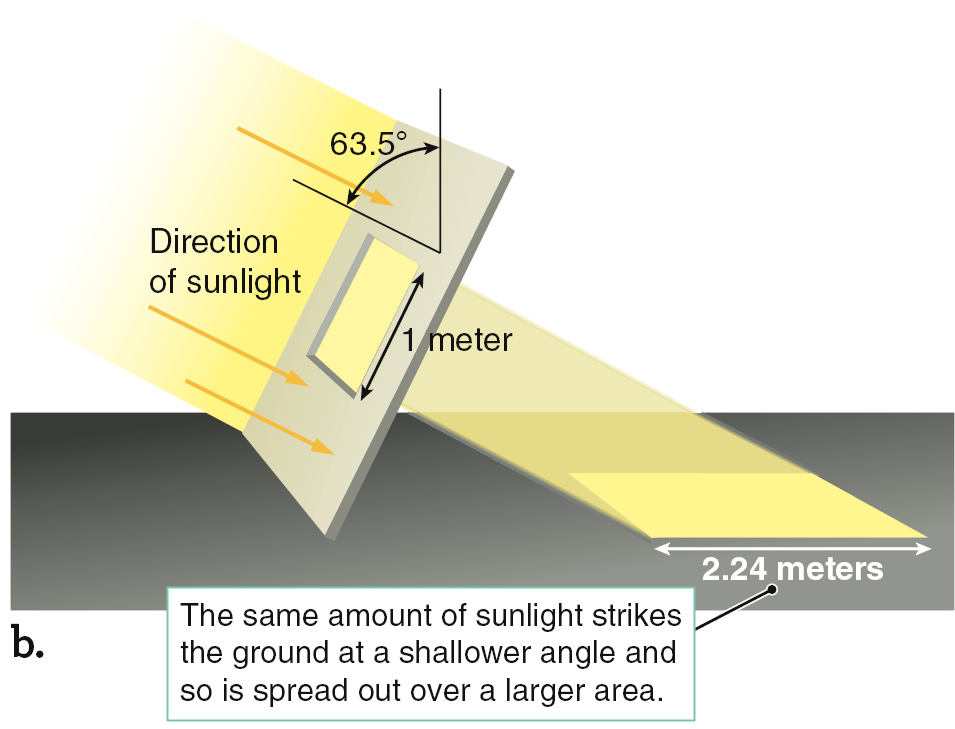

Precession of the Equinoxes

Two thousand years ago, when Ptolemy and his associates were formalizing their knowledge of the positions and motions of objects in the sky, the Sun appeared in the constellation Cancer on the first day of northern summer and in the constellation Capricornus on the first day of northern winter. Today, the Sun is in Taurus on the first day of northern summer and in Sagittarius on the first day of northern winter. Why have the constellations in which solstices appear changed? Two motions are actually associated with Earth and its axis: Earth spins on its axis, but its axis also wobbles like the axis of a spinning top slowing down (Figure 2.18a). The wobble is very slow: the north celestial pole takes about 26,000 years to complete one circle in the sky. Polaris is the star we now see near the north celestial pole. However, if you could travel several thousand years into the past or the future, the point about which the northern sky appears to rotate would no longer be near Polaris. Instead, the stars would rotate about another point on the path shown in Figure 2.18b. That figure shows the path of the north celestial pole through the sky during one cycle of that wobble.

Astronomy in Action: The Earth-Moon-Sun System

The celestial equator is perpendicular to Earth’s axis. Therefore, as Earth’s axis wobbles, the celestial equator also must wobble. As it does so, the locations where the celestial equator crosses the ecliptic—the equinoxes—change as well. During each 26,000-year wobble of Earth’s axis, the locations of the equinoxes make one complete circuit around the celestial equator. That change of the position of the equinox, due to the wobble of Earth’s axis, is called the precession of the equinoxes.

CHECK YOUR UNDERSTANDING 2.2

If Earth’s axis were tilted by 45°, instead of its actual tilt of 23.5°, how (if at all) would the seasons be different from what they are now? (a) The seasons would remain the same. (b) Summers would be colder. (c) Winters would be shorter. (d) Winters would be colder.

d

Glossary

- revolves

- Motion of one object in orbit around another.

- year

- The time Earth takes to make one revolution around the Sun. A solar year is measured from equinox to equinox. A sidereal year, Earth’s true orbital period, is measured relative to the stars. Compare tropical year.

- zodiac

- The 12 constellations lying along the plane of the ecliptic.

- ecliptic plane

- The plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun. The ecliptic is the projection of that plane onto the celestial sphere.

- summer solstice

- 1. One of two points where the Sun is at its greatest distance from the celestial equator. 2. The day on which the Sun appears at that location, marking the first day of summer (about June 20 in the Northern Hemisphere and December 21 in the Southern Hemisphere). Compare winter solstice. See also autumnal equinox and vernal equinox.

- winter solstice

- 1. One of two points where the Sun is at its greatest distance from the celestial equator. 2. The day on which the Sun appears at that location, marking the first day of winter (about December 21 in the Northern Hemisphere and June 20 in the Southern Hemisphere). Compare summer solstice. See also autumnal equinox and vernal equinox.

- autumnal equinox

- 1. One of two points where the Sun crosses the celestial equator. 2. The day on which the Sun appears at that location, marking the first day of autumn (about September 22 in the Northern Hemisphere and March 20 in the Southern Hemisphere). Compare vernal equinox. See also summer solstice and winter solstice.

- vernal equinox

- 1. One of two points where the Sun crosses the celestial equator. 2. The day on which the Sun appears at that location, marking the first day of spring (about March 20 in the Northern Hemisphere and September 22 in the Southern Hemisphere). Compare autumnal equinox. See also summer solstice and winter solstice.

- Arctic Circle

- The circle on Earth with latitude 66.5° north, marking the southern limit where at least one day per year is in 24-hour daylight. Compare Antarctic Circle.

- Antarctic Circle

- The circle on Earth with latitude 66.5° south, marking the northern limit where at least one day per year is in 24-hour daylight. Compare Arctic Circle.

- tropics

- The region on Earth between latitudes 23.5° south and 23.5° north, where the Sun appears directly overhead twice during the year.

- precession of the equinoxes

- The slow change in orientation between the ecliptic plane and the celestial equator caused by the wobbling of Earth’s axis.

Answer

Answer Answer

Answer