The genetic code for every organism is housed in its DNA.

Figure Credit: Jezper/Shutterstock

The genetic code for every organism is housed in its DNA.

Figure Credit: Jezper/Shutterstock

Lab Learning Objectives

By the end of this lab, students should be able to:

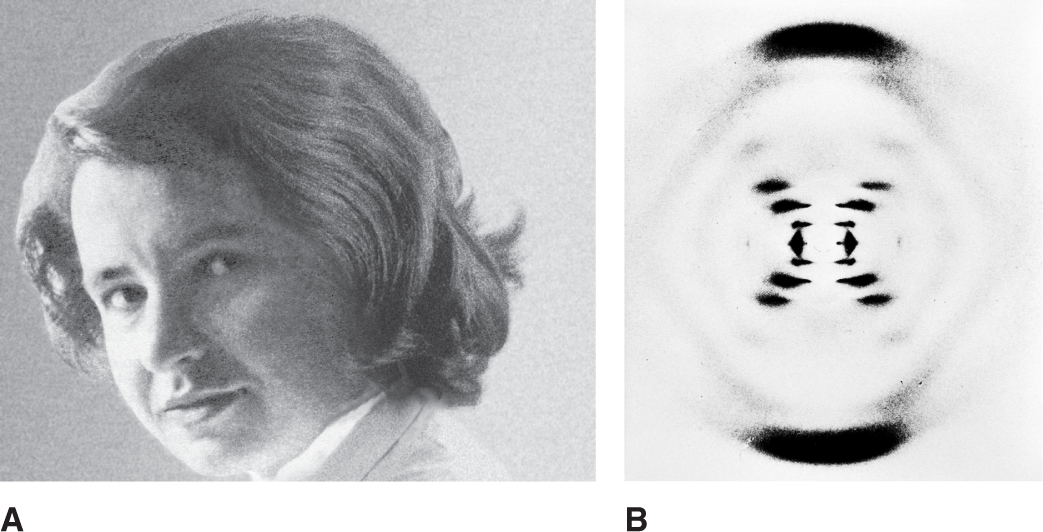

It is early March 1953. Researchers have been working off and on for several years on an interesting scientific problem. They have been trying to determine the structure of DNA. So far, scientists have identified the biological compounds adenine, thymine, guanine, and cytosine in DNA, and they recognize that these compounds appear to follow some sort of pattern: the quantities of adenine and thymine are the same, and the quantities of guanine and cytosine are the same. Thanks to the hard work of Rosalind Franklin (FIGURE 2.1), many X-ray photographs of DNA have been taken, which show that it has a compact, potentially helical structure. These first steps have made a significant contribution to the understanding of DNA’s overall shape and components, but many questions still remain. How is so much information kept in such a tiny package, and what could explain the paired quantities of adenine and thymine and of guanine and cytosine molecules?

After months and months, and a few frustrating missteps, researchers in England are about to answer these questions. The team has a new idea. What if the adenine and thymine bond together in the structure, and the guanine and cytosine also bond together? That idea would certainly explain their similar quantities, but is it real or another false lead?

Much of what we know about DNA and genetics today is possible because of the work of researchers like (A) Rosalind Franklin whose (B) X-ray photographs of DNA helped reveal its underlying structure.

Figure Credits: (A) Science Source; (B) Omikron/Science Source

Two scientists, Francis Crick and James Watson, get to work building, measuring, and refining a model of DNA based on this idea (and other ideas researchers have pieced together over the past year). The model they construct takes the shape of a double helix with bonded pairs of adenine–thymine and guanine–cytosine running along the core. Their excitement mounts, and over the coming days, weeks, and months, their structure is verified by other scientists and supported by further X-ray photography. This group of scientists has just revolutionized our understanding of life on Earth! Their work, which earns them a Nobel Prize, forms the foundation of our modern understanding of genetics and the passing of traits between generations. Understanding these foundational genetics concepts allows us to better understand how evolution happens, and in this lab we review these concepts with this goal in mind.