Human Femur

DISTINGUISHING BONES: SHAPES

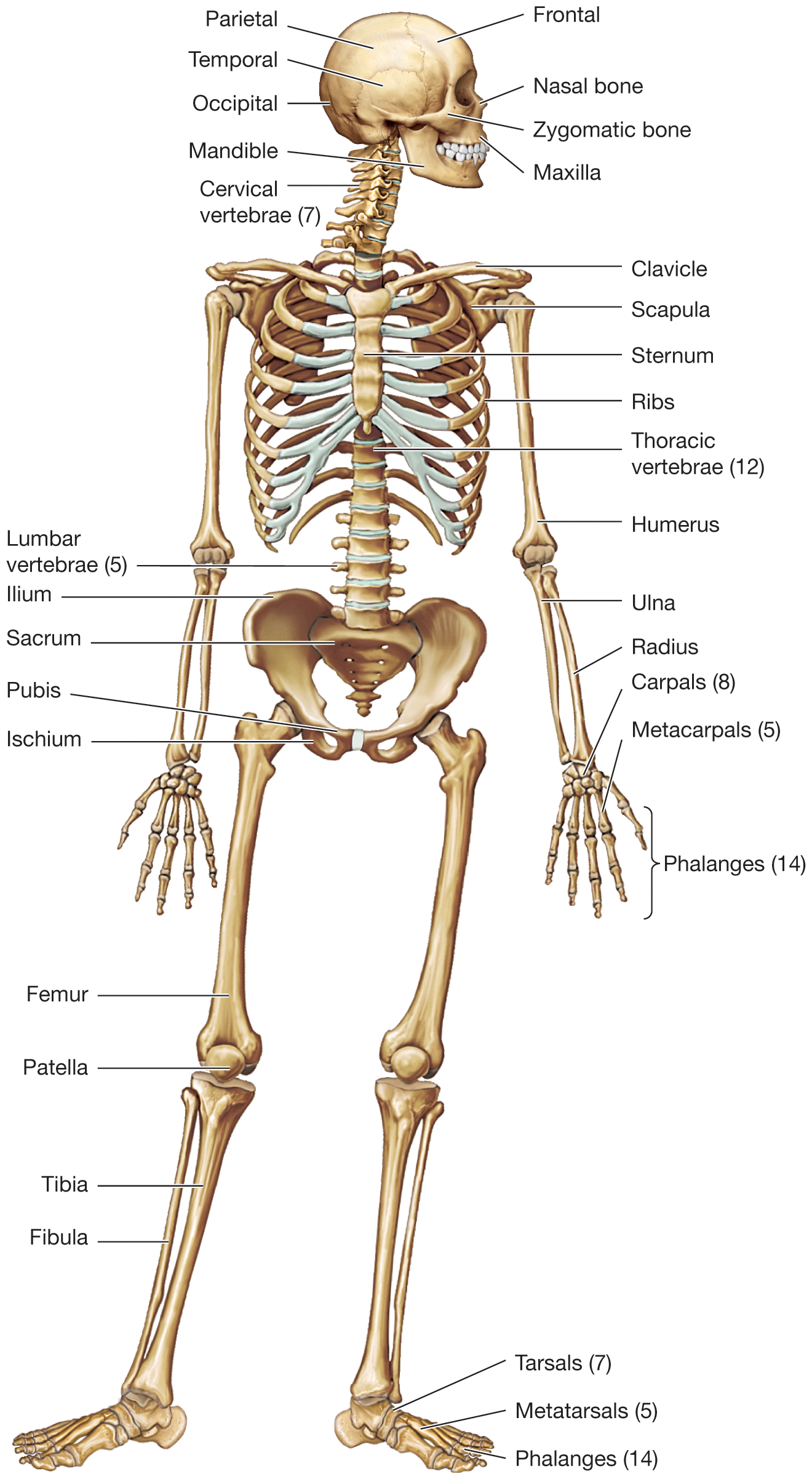

The major bones in this diagram of the human skeleton are labeled.

The human femur (thighbone) is a typical long bone. Notice the elongated shape with a middle shaft and two distinct ends.

Figure Credit: Courtesy of Ashley Lipps

Vertebrate organisms have a large number of different bones. Humans, for example, have a total of 206 bones (FIGURE 5.7). With so many bones, how do we distinguish among them? One way to do this is by looking at their overall shape. The bones of the human skeleton can be classified into four different categories based on their shape: long bones, short bones, flat bones, and irregular bones.

Long bones are made of a central shaft with distinct, slightly larger ends on each side (FIGURE 5.8). The long bones, joints, and associated muscles work together to help the arms and legs achieve their maximum potential when engaged in daily activities, such as bearing weight, facilitating movements such as flexion (bending) and extension (straightening), and carrying loads. In particular, having longer muscles in the arms and legs allows for a greater range of motion, and these longer muscles require longer bones for support and extension. A classic example of a long bone is the femur in your thigh. It has a long shaft in the middle and two distinct ends. Importantly, while the femur is a measurably long and large bone (typically the largest bone in the human body), not all long bones are large. For example, the long bones of the hand and fingers are much smaller than the femur, but they are still considered long bones because of their shape and how they grow. The ends of the long bones (called the epiphyses) have growth plates that separate them from the shaft to allow the bone to grow in length until the end of puberty (see Lab 7 for more information).

In contrast to long bones, short bones do not have a clear shaft. Instead, short bones are more cube-like in shape, with width and length dimensions that are similar (FIGURE 5.9). These short bones are often found in compact areas, and the presence of multiple, tightly packed short bones limits the range of motion in those areas. The bones of the wrist (the carpals) are classic short bones. They are cube-like, appearing relatively similar on most sides, and there are several of them packed into a small area, which limits mobility and gives stability within the wrist.

Human carpals (wrist bones) are typical short bones. Notice the cube-like shape. Remember, though, that the hand and finger bones (the metacarpals and phalanges) are long bones, despite their small size.

Figure Credit: Courtesy of Ashley Lipps

The human scapula (shoulder blade) is a typical flat bone. The generally flat shape that allows for extensive muscle attachment.

Figure Credit: Courtesy of Ashley Lipps

Flat bones are thin, platelike bones that make up a small proportion of the bones in the body (FIGURE 5.10). They consist of a layer of trabecular bone sandwiched between two thin layers of flat cortical bone. Flat bones may serve as broad areas for muscle attachment (as in the shoulder blade, or scapula) or as platelike protection for delicate structures (as in the bones of the skull, or cranium).

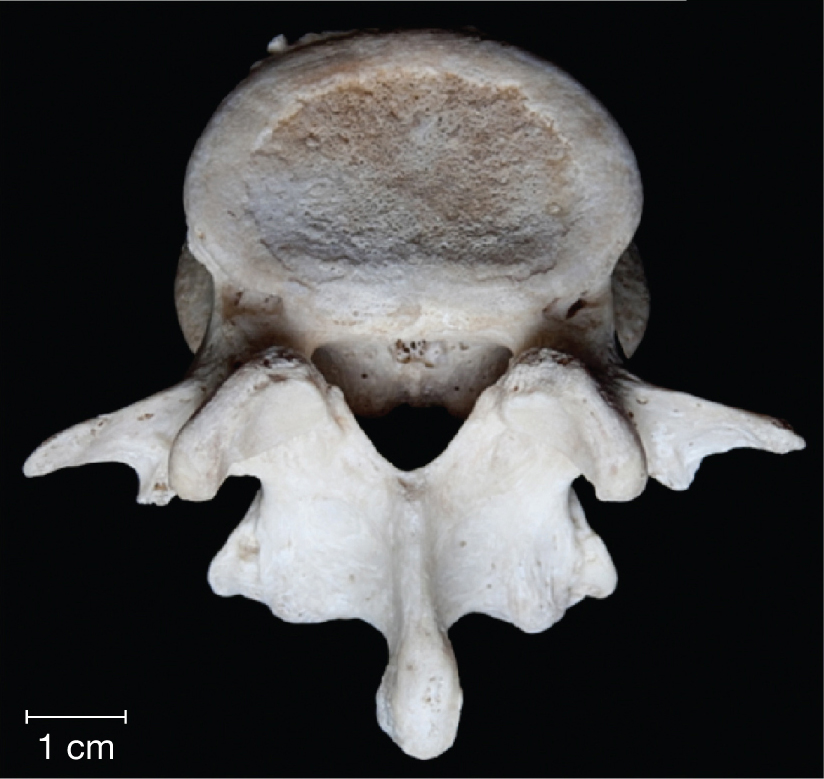

Irregular bones do not readily fit into any of the other three categories. They have complex and varied shapes (FIGURE 5.11). The bones of the spine, called vertebrae, are good examples of irregular bones. They are clearly not long bones because they do not have anything resembling a shaft. We can also rule out a classification of vertebrae as flat bones because they are too thick and fat to be part of the platelike group of bones. At first they might appear to be short bones because of the cube-like shape of the vertebral body. However, on closer consideration, it becomes apparent that the specialized spines sticking out of the vertebrae (which serve to anchor key ligaments of the spine) make the overall shape of these bones highly unusual and less cube-like. The vertebrae don’t qualify as long bones, short bones, or flat bones; therefore, they are placed in the catchall category of irregular bones.

A human vertebra (back bone) is a typical irregular bone. It does not easily fit into the other shape categories because it is not elongated, cube-like, or flat. It has a unique, irregular shape.

Figure Credit: Courtesy of Ashley Lipps

Glossary

- long bone

- a bone with an elongated middle shaft and distinct, slightly larger ends

- short bone

- a bone with a cube-like shape, with similar width and length dimensions

- flat bone

- a platelike bone consisting of a layer of trabecular bone sandwiched between two thin layers of flat cortical bone

- irregular bone

- a bone with a complex shape that is not easily classified as long, short, or flat