Political Conflict and Competition

THE PARTY SYSTEM AND ELECTIONS

Russia has yet to see the formation of political parties with clear ideologies and political platforms. Over the years, multiple parties have risen and disappeared between elections. Given Putin’s consolidation of political power, it might be tempting to argue that the country has largely become once again a one-party state, controlled by the pro-Putin party United Russia. However, there can be surprises. In the 2011 Duma elections, the main opposition parties captured nearly half of the seats in the Duma. This result challenges the view that United Russia or any one party is impervious, as well as the idea that Russian society is unable or unwilling to challenge those in power. That said, recent elections such as those in 2021 appear to exhibit more brazen voter fraud on the part of the government, reflecting perhaps the nervousness of those in power.11

THE PARTY OF POWER: UNITED RUSSIA Although so-called parties of power have since 1991 consistently represented the largest segment of parties in the Duma, they cannot be described in ideological terms. Russia’s parties of power can be defined as those parties created by political elites to support those elites’ political aspirations. Typically, these parties are highly personalized, lack specific ideologies or clear organizational qualities, and have been created by political elites during or following their time in office. For example, the Our Home Is Russia Party was created in advance of the 1995 Duma elections as a way to bolster support for Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin and President Yeltsin. Subsequently, in the 1999 elections, Unity was created to bolster Putin’s campaign. After Unity beat Fatherland–All Russia handily in the Duma elections, in 2001 the two parties merged to form United Russia. Drawing on Putin’s popularity and the government’s increased control over the electoral process, United Russia swept the 2003 elections and has won a majority of seats ever since (as well as extending its reach over local governments). As of the 2021 elections, United Russia holds 325 of 450 Duma seats—a supermajority that gives it the ability to change the constitution without needing the support of any other party.

Although headed by former prime minister Medvedev, United Russia boasts a cult of personality around Putin, a youth wing that advances the cause of the party, and party membership as a means of access to important jobs in the state and economy.12 United Russia’s campaign platforms have emphasized stability and conservatism, economic development (though this has receded as economic difficulties have mounted), and increasingly the restoration of the country as a “great power” in international politics. To contrast the country with what is portrayed as the immorality of the West (exemplified by such things as support for LGBTQ rights), United Russia has also increasingly positioned itself as the defender of traditional values.

The 2007 Duma elections were widely regarded as evidence that Russia could no longer be considered democratic, even according to the most generous definition of the term. The media, largely in the hands of the state, gave overwhelming support to United Russia. Observers concluded that the elections were not fair, did not meet basic standards for democratic procedures, and have become only more fraudulent over time. And yet, in 2011, United Russia suffered a major upset when over half of the popular vote went to several opposition parties (though none represents significant opposition to the Kremlin). In 2016 and again in 2021, United Russia managed to reclaim its dominant role in the Duma through a mixture of media control, harassment, and voter fraud. Turnout in 2021 was estimated to be a record low, at less than 40 percent.13 United Russia is an increasingly unpopular party due to its reputation for corruption and declines in standard of living, but there is little evidence that any other party has the capacity to challenge it.

COMMUNIST AND LEFTIST PARTIES Before the rise of United Russia, the strongest and most institutionalized party was the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF), successor of the Soviet-era organization. In the 1995 elections, the CPRF reached its peak, becoming the largest single party in the Duma and raising the fear among many that the country would return to communist rule. However, since that time, its vote share has declined, averaging between 10 and 20 percent of the vote and shares of the seats in the Duma. Even at that small level, it remains the second-largest party in the Duma.

The CPRF differs from most other post-communist parties in eastern Europe, many of which broke decisively from their communist past in the 1990s and successfully recast themselves as social-democratic organizations. In contrast, the CPRF remains close to its communist ideology and rejects Western capitalism and globalization. It also embraces the Stalinist period and has called for the return of the country to Stalinist ideals. The CPRF criticizes the government and United Russia but is careful not to attack Putin. As the Russian population ages, the CPRF has lost much of its traditional base; however, as the second-largest party, it enjoys protest votes from those opposed to United Russia. There are some suggestions that the CPRF may find a new base of support among Russians born after 1991, who have struggled economically. If so, the party could reemerge as a force in the future. For now, it runs a distant second behind United Russia.

|

|

CONCEPTS IN ACTION |

A much newer party, A Just Russia, can also be placed in the leftist camp. Founded in 2006 as a merger of several smaller parties, A Just Russia defines itself as a social-democratic party along European lines. Its platform emphasizes social justice and reducing inequality, and in general its ideological profile is perhaps clearer than that of any other party in the Duma. Unlike the CPRF, A Just Russia has been considered by many to be little more than a facade, supported (if not created) bythe Kremlin to provide a veneer of multiparty democracy. But again, the 2011 Duma elections confounded many assump-tions. A Just Russia came in third, with approximately 13 percent of the vote, and its more confrontational tone sug-gested that it might be-come a force in its own right. However, the party quickly resumed its loyalty to the Kremlin, expelling party members who had taken part in public demonstrations against Putin during the 2011 elections. In the Duma vote to annex Crimea after Russia’s invasion in 2014, only one member of parliament, Ilya Ponomarev of A Just Russia, voted no (and was subsequently expelled from the country). In the 2021 elections, A Just Russia slipped to the smallest party in the Duma, with only 7 percent of the vote. It currently holds 27 seats.

NATIONALIST PARTIES During the 1990s, one of the most infamous aspects of the Russian party spectrum was the strength of extreme nationalism. That faction is manifested by the ill-named Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR). Neither liberal nor democratic, the LDPR espouses a rhetoric of nationalism, xenophobia, and anti-Semitism, calling for such things as the reconstitution of the Soviet Union (perhaps by force) and exhibiting general hostility toward the West.

In the 1993 elections, many observers were shocked by the LDPR’s electoral strength and its gain of 14 percent of the seats in the Duma. Subsequently, the LDPR’s fortunes have waned. Over the past 20 years it has earned around 10 percent of the vote, and in 2021 it gained 21 seats, making it the third largest party in the Duma. The survival of the party can be attributed in part to the LDPR’s consistent support for Putin and his government; indeed, many observers suspect that the LDPR was created and is supported by the government to serve as a pseudo-opposition that can be controlled.14

LIBERAL PARTIES Despite Russia’s move toward capitalism, liberalism has made relatively few inroads into political life, and even these have declined of late. During the 1990s, liberalism’s standard bearer in Russia was the party Yabloko, whose pro-Western and pro-market economy stance drew support from white-collar workers and urban residents in the major cities. Never a major force, Yabloko has seen its electoral fortunes decline to such an extent that in recent Duma elections it has failed to gain a single seat in the legislature. In 2021, the party won less than 2 percent of the vote in the proportional representation portion of the ballot. It currently holds only a few seats in regional legislatures and in city governments in Moscow and St Petersburg. Also in 2021, a new liberal party known as New People gained 15 seats in the Duma; while it may develop to become a successor to Yabloko, others suspect that New People is largely a creation of the government to maintain the facade of multiparty politics and siphon support away from true opposition actors like Navalny.

Why has liberalism found such rocky soil in Russia? Several factors are at work. First, given the historically statist and collectivist nature of Russian politics, a liberal political ideology is not likely to find a wide range of popular support. Infighting and a lack of strong leadership within liberal parties have not helped. Finally, worsening relations between Russia and the West have also served to tarnish liberalism as a foreign ideology associated with Russian subservience. That said, surveys indicate that there is stronger support for individualism and private business among those under 30, who have spent their entire adult lives under Putin.15

CIVIL SOCIETY

As with political parties, civil society in Russia developed in fits and starts. Before the 1917 Russian Revolution, civil society was weak, constrained by authoritarianism, feudalism, and low economic development. With the revolution, what little civil society did exist quickly came under the control of the Soviet authorities, who argued that only the party could and should represent the “correct” interests of the population. With the advent of glasnost in the 1980s, however, civil society slowly began to reemerge.

After 1991, civil society grew dramatically in Russia. An array of movements and organizations filled the gaps left in the aftermath of one-party rule. However, during the Putin administration civil society came under state pressure and control, especially those groups that openly criticized the government. Tools to control civil society include the tax code, used to investigate sources of income; the process of registering with authorities, which can be made difficult; and police harassment and arrest on various charges ranging from tax evasion to divulging state secrets. Still, antigovernment protests attended by thousands have erupted regularly, suggesting that there remains a current of social activism that could translate into a revived civil society. Not surprisingly, Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012 ushered in a new wave of restrictions, which were subsequently tightened in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A 2022 law on “foreign agents” restricted civic organizations that had relied on foreign support or “influence,” leading to the banning of several groups by the Russian Supreme Court. This included Memorial, one of the oldest NGOs in Russia, which focused on remembering the victims of Soviet rule and promoting democracy.16

Another notable effect of the restrictions on civil society is in the area of religion. As the Russian government has turned more toward nationalism as a source of legitimacy, it has also emphasized Orthodox Christianity as a central part of what makes Russia unique (and distinct from the West and Western liberalism). In turn, the Russian government has increasingly restricted the ability of many religious groups to proselytize, build seminaries, publish their literature, or run educational programs, and it has relied on anti-extremism legislation to justify these actions. The return of Orthodox Christianity as a quasi–state religion has been accompanied by attacks on liberal activism, such as the arrest of members of the punk band Pussy Riot, several of whom were jailed in 2012 for two years on charges of religious hatred.17

Civil society has been restricted in Russia not just through direct government control but also through limitations on channels that would allow it to spread information—specifically, the media. The collapse of communism saw the emergence of private Russian media that for the first time were able to speak critically on an array of issues. This is not to say that the media were truly independent; the most powerful segments of the media, such as radio and television, remained in the hands of the state or came under the control of wealthy individuals with ties to Yeltsin. Similarly, the media’s owners came to support Putin during his consolidation of power, viewing him as the successor to Yeltsin who would preserve their power. Despite this support, Putin soon put strong economic pressure on much of the independent media, employing economic and legal tactics to acquire them and curb their editorial independence.

During the past decade, all of the largest private television stations have come under direct state ownership or have become indirect state-controlled firms. With nationalization, the Russian media have become even less diverse and are clearly oriented toward supporting those in power. Until 2022, a few small independent media outlets remained, but following the invasion of Ukraine new laws criminalized objective reporting on the war, making even the use of the word “war” prohibited and subject to prison terms. As a result, those remaining fragments of independent media either closed or went into exile.

The domestic media have become a consistent purveyor of conspiracy theories that tend to center around the efforts of the United States and the European Union to destroy Russia. Such arguments have been especially pronounced since 2014 when Russia first attacked Ukraine. Russia denied the presence of its own troops in Crimea and eastern Ukraine while arguing that U.S. troops were on the ground, and it claimed that the Malaysian Airlines flight destroyed over Ukraine had been shot down by the CIA. In terms of press freedom, Russia is ranked 155th out of 180 countries by the organization Reporters without Borders.18 The repression of civil society and free speech indicates that Putin, and those around him, worry that public opposition could eventually bring down the government, as they did in Ukraine in 2014.

More information

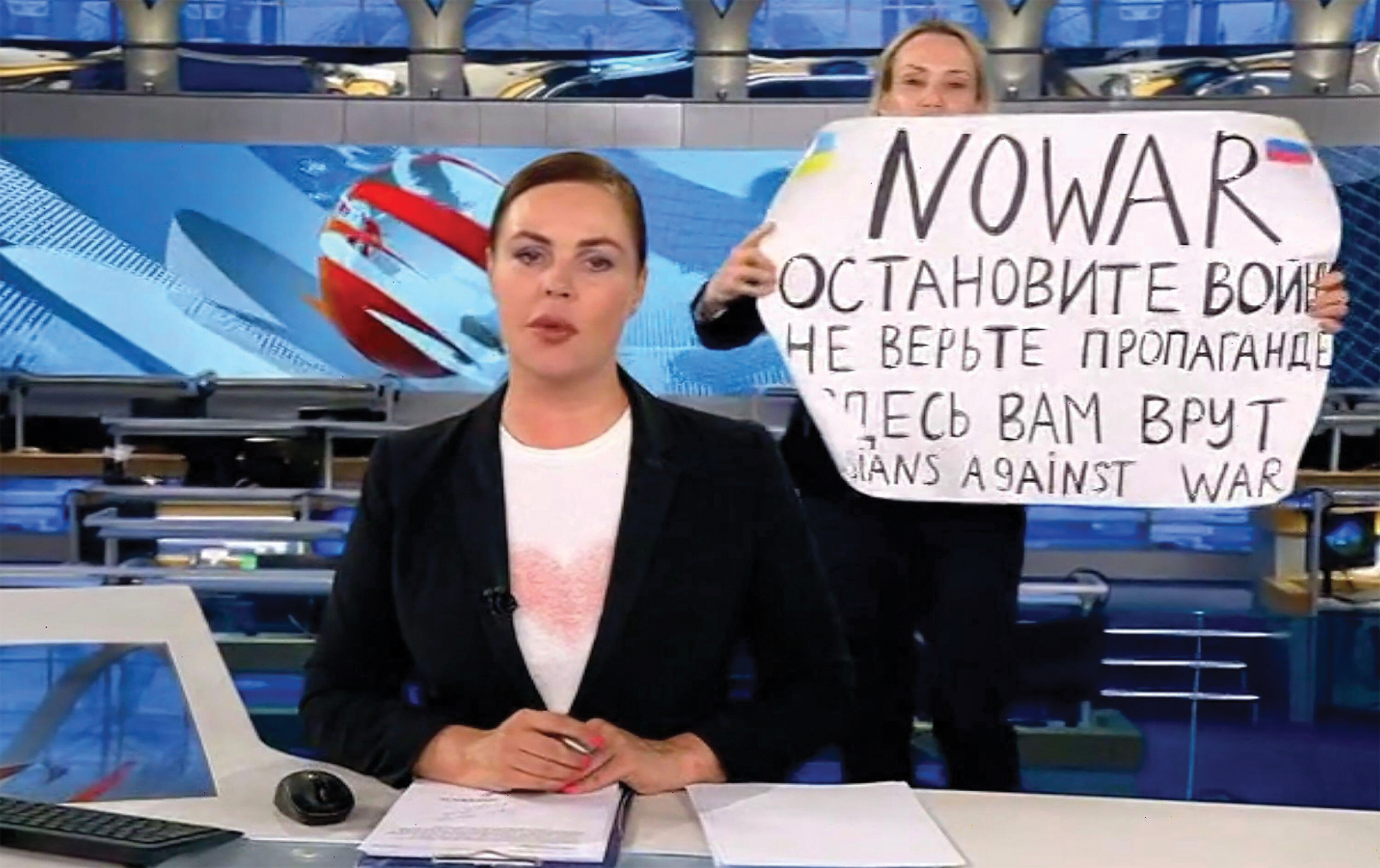

A photo of a news reporter sitting at a desk in front of news screens. A woman behind her holds a sign with Russian text and says “No War”.

When Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2022, Russian authorities restricted what the media could share with viewers. One reporter staged a protest during an evening news segment, holding a sign that read, “No war. Stop the war, don’t believe the propaganda. They lie to you here, Russians against war.”

Endnotes

- “Researcher Says Raw Voting Data Points to Massive Fraud in United Russia’s Duma Victory,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, September 21, 2021, www.rferl.org/a/russia-election-fraud-shpilkin/31472787.html (accessed 2/18/23).Return to reference 11

- Andrew Konitzer and Stephen K. Wegren, “Federalism and Political Recentralization in the Russian Federation: United Russia as the Party of Power,” Publius 36, no. 4 (Fall 2006): 503–22.Return to reference 12

- Heather A. Conley and Andrew Lohsen, “Where Does Russian Discontent Go from Here? Russia’s 2021 Election Considered,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 23, 2021, www.csis.org/analysis/where-does-russian-discontent-go-here-russias-2021-election-considered (accessed 2/18/23).Return to reference 13

- For more on parties in Russia, see Susanne A. Wengle, ed., Russian Politics Today (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).Return to reference 14

- World Values Survey, Wave 7, www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSOnline.jsp (accessed 2/18/23).Return to reference 15

- “Russia: New Restrictions for ‘Foreign Agents,’” Human Rights Watch, December 1, 2022, www.hrw.org/news/2022/12/01/russia-new-restrictions-foreign-agents (accessed 2/18/23).Return to reference 16

- Masha Gessen, Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot (New York: Riverhead, 2014).Return to reference 17

- Reporters without Borders, “2022 World Press Freedom Index,” https://rsf.org/en/index (accessed 2/18/23).Return to reference 18

Glossary

- parties of power

- Russian parties created by political elites to support their political aspirations; typically lacking any ideological orientation

- United Russia

- Main political party in Russia and supporter of Vladimir Putin

- Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF)

- Successor party in Russia to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- A Just Russia

- A small party in the Russian Duma with a social-democratic orientation

- Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR)

- Political party in Russia with a nationalist and antidemocratic orientation

- Yabloko

- Small party in Russia that advocates democracy and a liberal political-economic system