|

|

CONCEPTS IN ACTION |

See the concept of sovereignty in action in India on p. 544.

What exactly do we mean by state? Political scientists, drawing on the work of the German scholar Max Weber, typically define the state as the organization that maintains a monopoly of force over a territory.2 This definition of what a state is and does may seem severe, but a bit of explanation should help flesh out this concept. One of the most important elements of a state is what we call sovereignty, the ability to carry out actions and policies within a territory independently of external actors and internal rivals. In other words, a state needs to be able to act as the primary authority over its territory and the people who live there, passing and enforcing laws, defining and protecting rights, resolving disputes between people and organizations, and generating domestic security.

|

|

CONCEPTS IN ACTION |

See the concept of sovereignty in action in India on p. 544.

To achieve this, a state needs power, typically (but not only) physical power. If a state cannot defend its territory from outside actors such as other states, then it runs the risk that its rivals will interfere with its authority, inflicting damage, taking its territory, or destroying the state outright. Similarly, if the state faces powerful opponents within its own territory, such as organized crime or rebel movements, its rules and policies may be undermined. Thus, to secure control, a state must be armed. To protect against international rivals, states need armies. And in response to domestic rivals, states need police forces. In fact, the word police comes from an old French word meaning “to govern.”

A state is thus a set of institutions that wields the most force within a territory, establishing order and deterring challengers from inside and out. In so doing, it provides security for its subjects by limiting the danger of external attack and internal crime and disorder—both of which threaten the state and its citizens. In some ways, a state (especially a nondemocratic one) is a kind of protection racket—demanding money in return for the maintenance of security and order, staking out turf, defending those it protects from rivals, settling internal disputes, and punishing those who do not pay.3

IN FOCUS The State Is . . .

But most states are far more complex than mere entities that apply force. Unlike criminal rackets, the state is made up of a large number of institutions that are engaged in the process of turning political ideas into policy. Laws and regulations, property rights, health and labor, the environment, and transportation are but a few policy areas that typically fall under the responsibility of the state. Because of these responsibilities, the state serves as a set of institutions (ministries, offices, army, police) that society deems necessary to achieve basic goals. When there is a lack of agreement on these goals, the state must attempt to reconcile different views and seek (or impose) consensus.

The public views the state as legitimate, vital, and appropriate. States are thus strongly institutionalized and not easily changed. Leaders and policies may come and go, but the state remains, even in the face of crisis, turmoil, or revolution. Although destruction through war or civil conflict can eliminate states altogether, even this outcome is unusual, and states are soon re-created. Thus, the state is defined as a monopoly of force over a given territory, but it is also the set of political institutions that helps create and implement policies and resolve conflict. It is, if you will, the machinery of politics, establishing order and turning politics into policy. Thus, many social scientists argue that the state, as a bundle of institutions, is an important driver of economic development, the rise of democracy, and other processes.

Beyond state, a few other terms need to be defined. First, we should make a distinction between a state and a regime, which is defined as the fundamental rules and norms of politics. More specifically, a regime embodies long-term goals that guide the state regarding individual freedom and collective equality, where power should reside, and how power should be used. At the most basic level, we can speak of a democratic regime or a nondemocratic one. In a democratic regime, the rules and norms of politics give the public a large role in governance, as well as certain individual rights and liberties. A nondemocratic regime, in contrast, limits public participation and favors those in power. Both types of regimes can vary in the extent to which power is centralized and in the relationship they create between freedom and equality. The democratic regime of the United States is not the same as that of Canada; China’s nondemocratic regime is not the same as Cuba’s or Syria’s. Some of these regime differences can be found in basic documents such as constitutions, but often the rules and norms that distinguish one regime from another are informal, unwritten, and implicit, requiring careful study. Finally, we should also note that in some nondemocratic countries where politics is dominated by a single individual, observers may use regime to refer to that leader, emphasizing the view that all decisions flow from that one person. As King Louis XIV of France famously put it, L’état, c’est moi (“I am the state”). However, the term regime is not inherently negative any more than the terms rules or norms are.

IN FOCUS A Regime Is . . .

In summary, if the state is a monopoly of force and a set of political institutions that secure the population and generate policy, then the regime is defined as the norms and rules that establish the proper relation between freedom and equality and the use of power toward that end. If the state is the machinery of politics, like a computer, one can think of a regime as its software, the programming that defines its capabilities. Each computer runs differently, and more or less productively, depending on the software installed. Over time, software becomes outdated and unstable, and machines become less efficient or even crash. However, states and regimes are not like consumer electronics that we can simply throw away or upgrade. In fact, as we know all too well, it can be disastrous to upgrade from one operating system to another. No matter how hard we try to erase old political institutions, many aspects of them tend to persist. This is a particularly big obstacle to reforming or transforming states and regimes—building democracy, reducing corruption, or ameliorating ethnic conflict all involve changing existing, deeply embedded institutions. We cannot simply reformat or reboot existing institutions, and even formal attempts to do so are often incomplete or stillborn.

FRANCE

SOUTH AFRICA

RUSSIA

Regimes are an important component of the larger state framework. Regimes do not easily or quickly change, although they can be transformed or altered, usually by dramatic social events such as revolutions and national crises. Most revolutions, in fact, can be seen as revolts not against the state or even the leadership but against the current regime—to overthrow the old rules and norms and replace them with new ones.

One good example can be seen in France. In 1789, the French Revolution overthrew the monarchy and established what is known as the First Republic, whose constitution for the first time placed power in the hands of the people and the legislature. Since then a number of important political events—the rise and fall of Napoleon, the Franco-Prussian War, and World War II—triggered the subsequent collapse of existing political institutions and thus necessitated the construction of a new set of rules and political norms. Some of these regimes were more strongly institutionalized than others. The Fourth Republic, which lasted between 1946 and 1958, was notably unstable, with power vested in the legislature and divided among a number of polarized political parties. As the country struggled with decolonization in the late 1950s, France teetered on the verge of a military coup. Former general Charles de Gaulle, noted for his role as leader of the Resistance during World War II, was brought out of retirement to prevent violence, and the legislature suspended the constitution. In 1958, the Fifth Republic introduced a directly elected presidency and a new electoral system meant to limit the number of parties. These institutional changes were meant to address past political instability by concentrating greater power in the hands of the executive.

In another example, during most of the twentieth century South Africa functioned under a racist regime that institutionalized discrimination against the majority non-White population, severely limiting its political and economic rights. After many decades of domestic and international opposition, the government agreed to free elections that paved the way for a political transition. The end of White apartheid rule led to the drafting of an entirely new constitution in 1996 that extended a range of civil rights to all South Africans. One of these new rights was the official recognition of 11 national languages, meant to address the substantial ethnic diversity repressed under the previous regime.

But changes in constitutions do not always mean that there has been an immediate or a complete change in the regime. For example, South Africa’s media still face government pressure and censorship in spite of democratization, in part as a result of national security laws retained from the apartheid era.

A failed coup in the Soviet Union in 1991 led to the end of the communist regime and the breakup of the Soviet Union into 15 new states, including Russia. However, even this dramatic change did not lead to the institutionalization of democracy, and many communist-era political values and norms have persisted. Most notable is the continued centralization of power around the president and a narrow ruling elite, known as the siloviki, or “men of power.” These individuals largely hail from the communist-era security services. Certainly, most would regard the cases of South Africa and Russia as regime changes based on their profound political transformations. However, our broader point is that even in the case of regime change a much wider range of institutions, formal and informal, do not disappear and, in some cases, may subvert new political rules. The United States learned this, tragically, in the case of Iraq, where there was a widespread belief that the elimination of President Saddam Hussein would lead to a relatively straightforward transition to democracy.

Our third term related to the concepts of state and regime is the most familiar one: government. Government can be defined as the leadership that runs the state. If the state is the machinery of politics, and the regime its programming, then the government operates the machinery. The government may consist of democratically elected legislators, presidents, and prime ministers, or it may be made up of leaders who gained office through force or other nondemocratic means. Whatever their path to power, governments all hold particular ideas regarding freedom and equality, and they all attempt to use the state to realize those ideas. But few governments are able to act with complete autonomy in this regard. Democratic and nondemocratic governments alike must confront the existing regime that has built up over time. Push too hard against an existing regime, and resistance, rebellion, or collapse may occur. For example, Mikhail Gorbachev’s attempt to transform the Soviet Union’s regime in the 1980s contributed to that country’s dissolution. Today, the Chinese government—and many of its citizens—fear similar chaos if political reforms were to allow for greater political competition.

IN FOCUS Government Is . . .

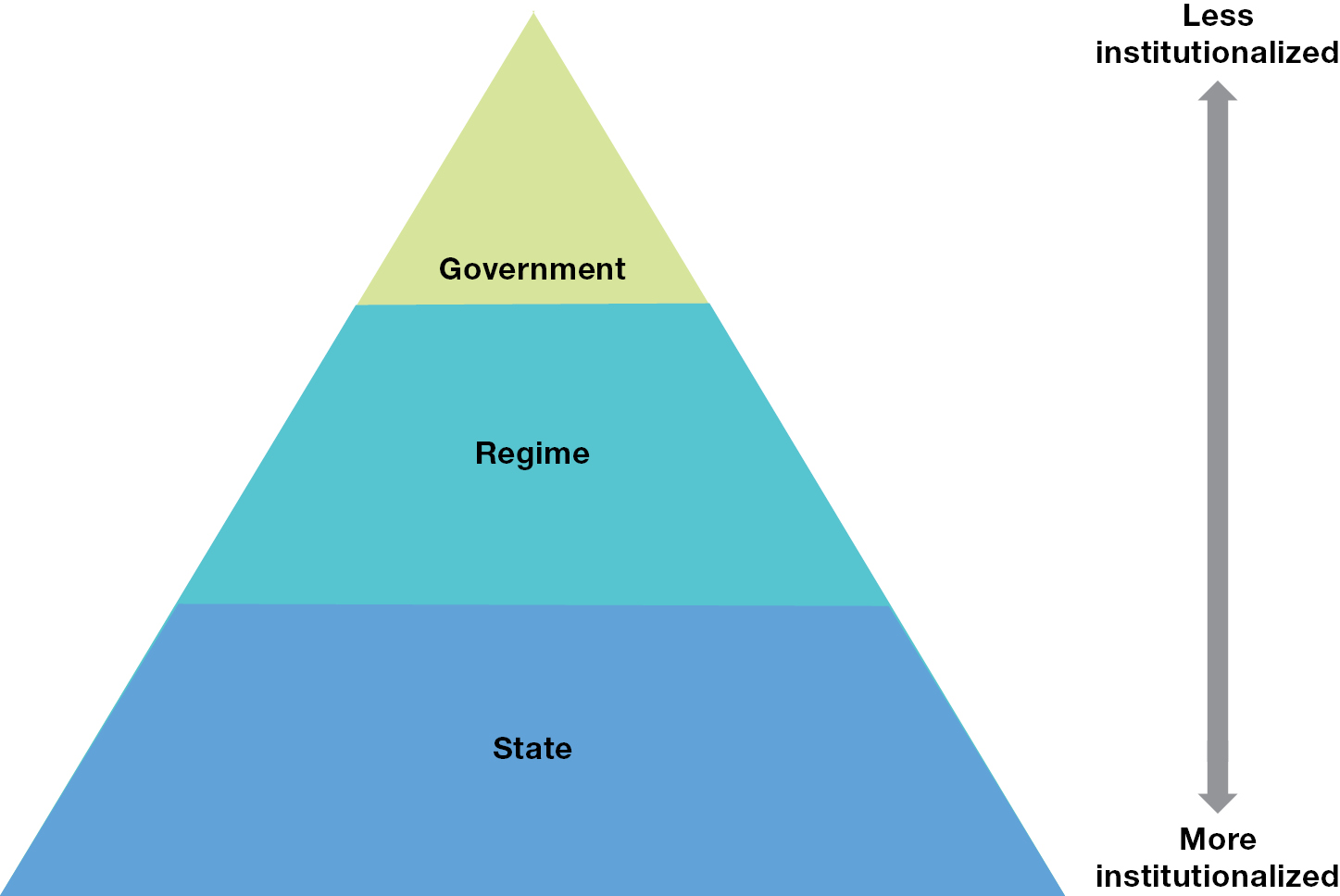

In part because of the power of regimes, governments tend to be weakly institutionalized—that is, the public does not typically view those in power as irreplaceable or believe that the country would collapse without them (Figure 2.1). In democratic regimes, governments are replaced fairly frequently, and even in non-democratic settings rulers are continuously threatened by rivals and by their own mortality. Governments come and go, whereas regimes and states may live on for decades or centuries.

Figure 2.1 is a diagram of a triangle split into three levels: Government, Regime, and State. Next to the triangle is a double-headed arrow with less institutionalized at the top and more institutionalized at the bottom. Government is the least institutionalized, so it is at the top of the triangle. Regime is in the middle, and the state is at the bottom as the most institutionalized.

FIGURE 2.1 State, Regime, and Government

Governments are relatively less institutionalized than regimes and states. Governments may come and go, while regimes and states usually have more staying power.

Finally, the term country can be taken as shorthand for the political system that combines the entities defined so far—state, regime, government—as well as for the people who live within that system. We will often speak about various countries in this textbook, and when we do, we are referring to the entire political entity and its citizens.