Medieval Music Theory and Practice

Treatises in the age of Charlemagne and in the later Middle Ages reflected actual practice to a greater extent than the more speculative earlier writings. They always spoke of Boethius with reverence and passed along the mathematical fundamentals of scale building, intervals, and consonances that he transmitted from the Greeks. But reading Boethius did not help solve the immediate problems of singing intervals, memorizing chants, and, later, reading notes at sight. Theorists partially addressed these goals by establishing the system of eight modes, or toni (“tones”), as medieval writers called them.

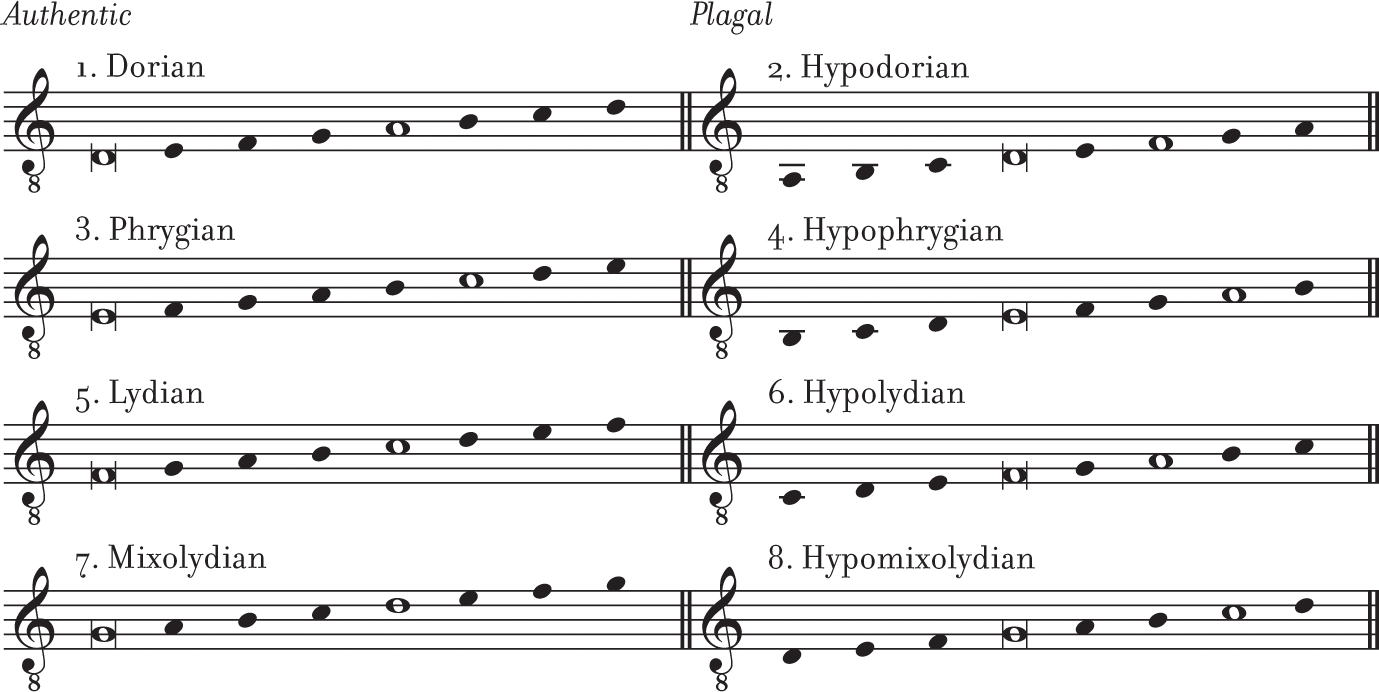

Example 2.3 The medieval church modes

More information

The medieval modal system developed gradually, achieving its complete form by the eleventh century. It encompassed eight modes, each defined by the sequence of whole tones and semitones in a diatonic octave built on a finalis, or final. In practice, this note was usually the last note in the melody. The modes were identified by numbers and grouped in pairs; the odd-numbered modes were called authentic, and the even-numbered modes plagal (collateral). Each pair of modes shared the same final (identified as bracketed whole notes in Example 2.3), but their melodies had different ranges: those belonging to the authentic modes rose above the final, and those in the plagal modes circled around or went farther below the final. The authentic modal scales may be thought of as analogous to white-key octave scales on a modern keyboard rising from the notes D (mode 1), E (mode 3), F (mode 5), and G (mode 7), with their corresponding plagals (modes 2, 4, 6, and 8) a fourth lower. These notes, of course, do not stand for specific “absolute” pitches — a concept foreign to plainchant and to the Middle Ages in general; they are simply a convenient way to distinguish the interval patterns, which are unique to each pair of modes, as partially shown in the example. In addition to the final, each mode has a second characteristic note, called the tenor or reciting tone (shown in Example 2.3 as whole notes), as in the psalm tones. Although the finals of the paired plagal and authentic modes are the same, their tenors are higher or lower in keeping with their ranges. The church modes also had Greek names (as shown in the example), although these were a misapplication of the ancient Greek scales. The modes became a primary means for classifying chants and arranging them in books for liturgical use. However, because many of the chants existed before the theory of modes evolved, their melodic characteristics do not always conform to modal theory.

For teaching sight-singing, the eleventh-century monk Guido of Arezzo (ca. 991–after 1033) proposed a set of syllables — ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la — to help singers remember the pattern of whole tones and semitone in the six steps (known as hexachords) that begin on C, G, or F. (This became known as solmization.) In this pattern (for example, C–D–E–F–G–A), a semitone falls between the third and fourth steps, and all other steps are whole tones. The syllables of solmization (also known as solfège or solfeggio) are still employed in teaching, except that in English we say do for ut and add a ti above la.

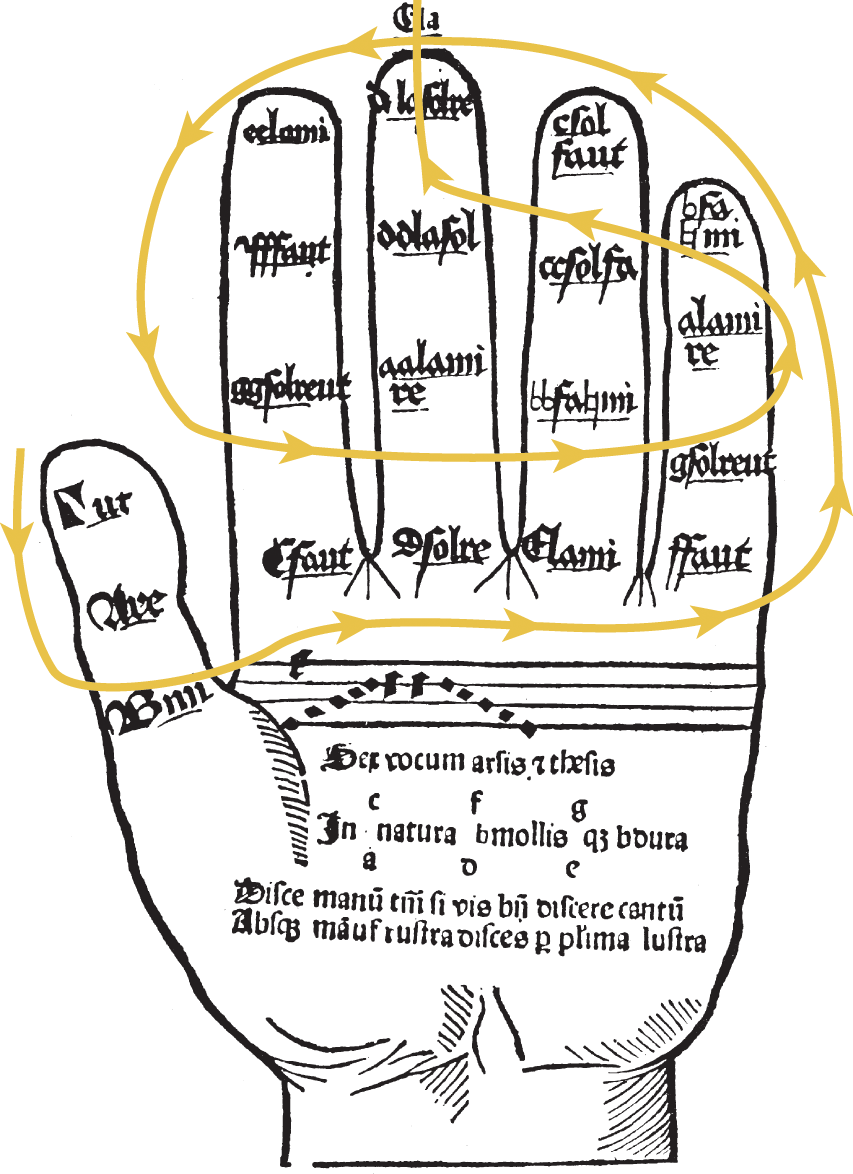

Followers of Guido developed a pedagogical visual aid called the “Guidonian hand” (Figure 2.14). Pupils were taught to sing intervals as the teacher pointed with the index finger of the right hand to the different joints of the open left hand. Each joint stood for one of the twenty notes that made up the musical system of the time; any other note, such as F♯ or E♭, was considered “outside the hand.” No late medieval or Renaissance music textbook was complete without a drawing of this hand.

In earlier stages of musical notation, scribes placed the note symbols, or neumes, above the text, sometimes at varying heights to indicate the relative size as well as direction of intervals (as in Figure 2.12). Eventually, one scribe conceived the idea of scratching a horizontal line in the parchment corresponding to a particular note and oriented the neumes around that line. This was a revolutionary idea: a musical sign that did not represent a sound, but clarified the meaning of other signs. In the eleventh century, Guido suggested an arrangement of lines and spaces from which evolved the modern staff. Guido’s scheme not only enabled scribes to notate (relative) pitches precisely, but also freed music from its dependence on oral transmission. The achievement proved to be as crucial for the history of Western music as the invention of writing was for literature.

More information

(Wikimedia Commons.)