NAWM 8Bernart de Ventadorn, Can vei la lauzeta mover

Medieval Song

Music outside the church spawned many types and forms of song. The oldest written specimens of secular music are songs with Latin texts, among them the goliard songs from the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Their poets and composers were students or clerics who exalted a libertine lifestyle, naming themselves after a fictitious and scurrilous patron, Bishop Goliath. The songs, preserved in numerous manuscript collections, celebrate three topics of interest to young men then, as now: wine, women, and satire. In most cases, however, the music does not survive in a notation precise enough to permit accurate modern transcriptions and performances.

The goliard songs, although written mostly in Latin, are early manifestations of literacy in the secular musical culture of western Europe. As the vernacular languages also gradually came to be written down, we begin to see glimpses of entire repertories — work songs, dance songs, lullabies, laments — that were lost over time. Among these are chansons de geste, praise songs that celebrate the deeds of past warriors and present rulers, and love songs, which became popular at the increasingly powerful courts of western Europe.

The people who sang these and other secular songs in the Middle Ages were the jongleurs (from the same root as English “jugglers”), or minstrels (from the Latin minister, “servant”), who were either itinerants or in service to a particular lord, or sometimes both. Jongleurs traveled alone or in small groups from village to village and castle to castle, earning a precarious living by performing tricks, telling stories, and singing or playing instruments. Figure 2.15 shows a juggler accompanied by a musician playing a wind instrument. Jongleurs especially were social outcasts, often denied the protection of the law and the sacraments of the Church. With the economic recovery of Europe in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, society became more stably organized, and towns sprang up. The minstrels’ situation improved, though for a long time people continued to regard them with a mixture of fascination and revulsion. In the eleventh century, minstrels organized themselves into brotherhoods, which later developed into guilds of musicians offering professional training, much as a modern conservatory does.

More information

(Photo 12/Alamy Stock Photo.)

Troubadours (male) and trobairitz (female, singular and plural) were poet-composers who flourished during the twelfth century in the south of France and spoke Provençal (also called the langue d’oc or Occitan). Trouvères were their equivalent in northern France. One theory is that the art of the troubadours took its inspiration in part from the Arabic love poetry cultivated in Moorish Spain and then spread quickly northward. The trouvères, who were active throughout the thirteenth century, spoke the langue d’oïl, the medieval French dialect that became modern French (oïl = oui, “yes”; oc = “yes” in Occitan).

Neither troubadours nor trouvères constituted a well-defined group. They flourished in castles and courts throughout France. Some were kings: others came from families of merchants, craftsmen, or even jongleurs but were accepted into aristocratic circles because of their accomplishments. Many of the poet-composers not only created their songs but sang them as well; those who did not entrusted the performance to a minstrel. The songs are preserved in collections called chansonniers (songbooks). About 2,600 troubadour poems survive, only a tenth with melodies; by contrast, two-thirds of the 2,100 extant trouvère poems have music. No other surviving body of secular tunes and lyrics is as large.

(Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, fonds français 854, fol. 121v)

The poetic and musical structures of the songs show great variety and ingenuity. Some are simple, others dramatic, suggesting two or more characters. Some of the dramatic ones were probably intended to be mimed; many obviously called for dancing. The dance songs may include a refrain sung by a chorus of dancers. An important structural feature of numerous trouvère (as opposed to troubadour) songs, the refrain is a line or two of poetry that returns with its own music from one stanza to another. The troubadours especially wrote complaints about love, the subject par excellence of their poetry. (See Figure 2.16.) But they also wrote songs on political and moral topics, songs that tell stories, and songs whose texts debate or argue esoteric points of chivalric or courtly love. Among these are several particular genres, such as the alba (dawn song), canso (love song), and tenson (debate song).

More information

(The Picture Art Collection/Alamy Stock Photo.)

Many old Occitan lyrics were openly sensual; others hid sensuality under a veil of fine amour, or “refined love.” The object of the passion they expressed was a real woman — usually another man’s wife — but she was adored from a distance, with such discretion, respect, and humility that the lover is made to seem more like a worshipper content to suffer in the service of his ideal love. The lady herself is depicted as so lofty and unattainable that she would step out of character if she condescended to reward her faithful lover. By playing on common themes in fresh ways through artfully constructed lyrics, the poets demonstrate refinement and eloquence, two main requirements for success in aristocratic circles. Thus, the entire poetic genre was more fiction than fact, addressed as much to other men (patrons whose wives were being flattered) as to women, and rewarded not by love, but by social status.

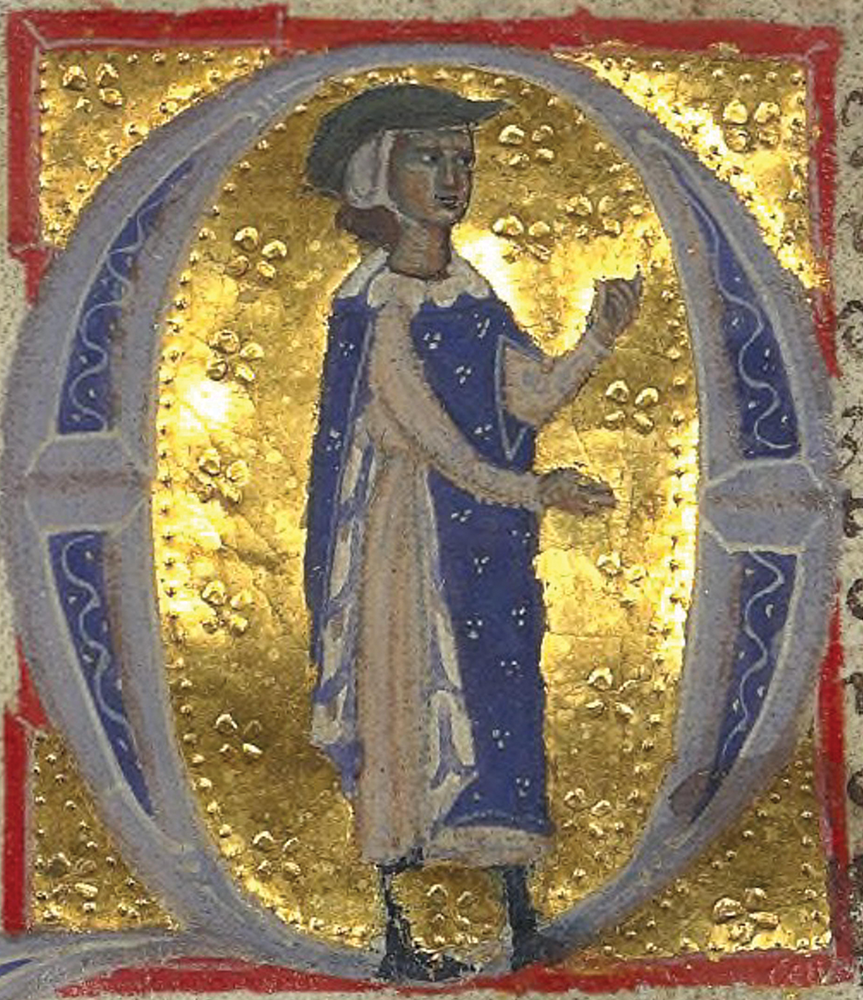

Among the best-preserved courtly songs is Can vei la lauzeta mover (When I see the lark beating; NAWM 8) by the troubadour Bernart de Ventadorn (ca. 1150–ca. 1180, Figure 2.17), one of the most popular poets of his time. Stories about his life assert that he was the son of a serf and baker in the castle of Ventadorn and rose to become the great lover of three noble ladies. Of the eight stanzas of Can vei la lauzeta mover, the second typifies the lover’s complaints that are the main subject of this repertory.

Ai, las! tan cuidava saberAlas! I thought I knew so much

d’amor, e tan petit en sai,of love, and I know so little;

car eu d’amar no • m posc tenerfor I cannot help loving a lady

celeis don ja pro non aurai.from whom I shall never obtain any favor.

Tout m’a mo cor, e tout m’a me,She has taken away my heart and myself,

e se mezeis e tot lo mon;and herself and the whole world;

e can se • m tolc, no • m laisset reand when she left me, I had nothing left

mas dezirer e cor volon.but desire and a yearning heart.1

Like Bernart’s song, or canso, the typical troubadour and trouvère text is strophic, with each stanza sung to the same melody. The settings are generally syllabic with an occasional short melismatic figure near the end of a line. Such a simple melody invites improvised ornaments and other variants as the singer moves from one stanza to the next. The range is narrow — a sixth, perhaps, or an octave. Because the songs have finals on C, D, and F, the entire body of works displays a certain coherence. The notation yields no clue to the rhythm of the songs: they might have been sung in a free, unmeasured style, or in long and short notes corresponding to the accented and unaccented syllables of the words. Most scholars now prefer to transcribe them as they do plainchant — in neutral note values without barlines.

TIMELINE The Middle Ages

Musical Events

386

Bishop Ambrose introduces responsorial psalmody in Milan

ca. 500

Boethius, De institutione musica

9th cent.

Earliest notated manuscripts of Gregorian chant

10th cent.

Monks at Saint Gall compose tropes (NAWM 5) and sequences (NAWM 6)

ca. 1025–28

Guido proposes system of solmization

11th cent.

Goliards flourish

ca. 1151

Hildegard, Ordo virtutum (NAWM 7)

ca. 1180

Bernart de Ventadorn dies

ca. 1212

Beatriz de Día dies

Historical Events

300

313

Constantine I issues Edict of Milan, proclaiming religious freedom in the Roman Empire

330

Constantinople becomes new capital of the Roman Empire

395

Separation of eastern and western Roman empires

397

Saint Augustine begins writing his Confessions

ca. 530

(Monastic) Rule of Saint Benedict; Benedictine order founded

590

Gregory I (“the Great”) elected pope

600s

Muslim conquests in asia, North Africa, and southern Europe (completed by 719)

768

Charlemagne becomes king of the Franks with his brother

789

Charlemagne orders Roman rite used throughout empire

800

Charlemagne crowned emperor by pope

800–821

Rule of Saint Benedict introduced in Frankish lands

1095–99

First Crusade

ca. 1100

Chanson de Roland, French epic poem

1147–49

Second Crusade

1300

1189–92

Third Crusade

1347–50

Plague devastates Europe

Each poetic line of a canso receives its own melodic phrase. The phrases join to make one long melody to accommodate a complete stanza of poetry. While Bernart’s melody is arranged in this manner, a variety of formal patterns emerges through variation, contrast, and the repetition of short, distinctive musical phrases. Many of the troubadour and trouvère melodies repeat the opening phrases or section before proceeding in a free style — for example, AAB, or, in more detail, ab ab cdef. Phrases are modified on repetition, and elusive echoes of earlier phrases are heard; but the main impression is one of freedom, spontaneity, and simplicity, although in fact both the music and poetry are very skillfully crafted.

Some of these features are illustrated in another canso — the only song by a trobairitz to survive with music — composed by the Comtessa Beatriz de Día (d. ca. 1212). A vida, or biographical tale, written about a century later describes Beatriz as a “beautiful and good woman, the wife of Guillaume de Poitiers. And she was in love with Rambaud d’Orange and made about him many good and beautiful songs.” In A chantar (To sing; NAWM 9) the countess berates her unfaithful lover and reminds him of her own worthy qualities. The song uses four distinct melodic phrases arranged in the form ab ab cdb.

NAWM 9Comtessa de Dia, A chantar

More information

(© DeA Picture Library/Art Resource, NY.)

The troubadours served as the model for a German school of knightly poetmusicians, the Minnesinger, who flourished between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. The Minne (love) of which they sang in their Minnelieder (love songs) was even more abstract than troubadour love and sometimes had a distinctly religious tinge. The music is correspondingly more sober. Some of the melodies are written in the church modes, while others sound as though they were built on major scales. Because of the rhythm of the texts, scholars think that the majority of the tunes were sung in triple meter. As in France, strophic songs were very common. Their tunes, however, were more tightly organized through melodic phrase repetition. A typical German poetic form called bar (AAB) inspired a common musical pattern: the melodic phrase A (called the Stollen) is sung twice for the stanza’s first two units of text, while the remainder, B (the Abgesang), containing new melodic material, is longer and sung only once.

The Middle High German texts include loving depictions of the glow and freshness of spring. There are also dawn songs, like the French alba, sung by the faithful friend who stands guard and warns the illicit lovers that dawn is approaching. A new genre is the Crusade song, recounting the experiences of those who renounced worldly comfort to join the Crusades (Christian military expeditions to recover the Holy Land from the Muslims). A famous example is the Palästinalied (Palestine song; NAWM 11) by Walther von der Vogelweide (ca. 1170?–ca. 1230?, Figure 2.18).

NAWM 11Walther von der Vogelweide, Palästinalied

(Oronoz, Madrid.)

One of the treasures of medieval song is the Cantigas de Santa María, a collection of over four hundred cantigas (songs) in Galician-Portuguese in honor of the Virgin Mary. The collection was prepared about 1270–90 under the direction of King Alfonso el Sabio (“the Wise”) of Castile and León (northwest Spain) and is preserved in four beautifully illuminated manuscripts (see Figure 2.19). Whether Alfonso wrote some of the poems and melodies is uncertain. Most songs in the collection relate stories of miracles performed by the Virgin, who was increasingly venerated from the twelfth century on. Cantiga 159, Non sofre Santa María (NAWM 12), tells of a cut of meat, stolen from some pilgrims, that Mary caused to jump about, revealing where it was hidden by the perpetrators. All the songs have refrains, perhaps performed by a group alternating with a soloist who sang the verses. Songs with refrains were often associated with dancing, a possibility reinforced by illustrations of dancers in the Cantigas manuscripts and by the dancelike rhythm of many of the songs.

NAWM 12Anonymous, Cantiga 159 Non sofre Santa María, from Cantigas de Santa María

Notes

- Text and translation are from Hendrik van der Werf, The Chansons of the Troubadours and Trouvères: A Study of the Melodies and Their Relation to the Poems (Utrecht, Netherlands: A. Oosthoek, 1972), pp. 91–95, which presents versions of the melody from five different sources, showing surprising consistency of readings. The dot splitting two letters of a word, as in “no•m,” stands for contraction.Return to reference 1