Where Does Cultural Variation Come From?

There are few greater challenges in the social sciences than identifying the causes of cultural variation. This issue has been explored from many disciplines outside of psychology, and we will consider some of those perspectives in this chapter. It is immediately apparent that cultures around the world vary, often tremendously, in their practices, social structures, diets, economic systems, technologies, religious beliefs, and psychology. Why cultures vary in these ways defies any single answer—rather, we can come to understand cultural variation by discussing several different forces that come into play.

Ecological and Geographical Variation

One approach is looking at the environments in which people live. By the late Pleistocene epoch (about 20,000 years ago), humans had already settled in a more diverse range of physical environments than any other species. And it is obvious that these habitats affected the ways people went about their daily lives. Some of the influences of the physical environment on culture are quite direct. For example, there are no large indigenous mammals in Hawaii, and native Hawaiians do not have any hunting traditions. This contrasts sharply with the !Kung of the Kalahari Desert who live in an environment surrounded by large animals and who derive much of their caloric intake by hunting them. The kinds of foods that are available within a given environment affect the kinds of foraging behaviors of the inhabitants.

“I don’t know how it started, either. All I know is that it’s part of our corporate culture.”

These ecological differences can have some indirect effects on cultures as well. Different physical surroundings do not just affect the diets of people; the different foraging behaviors can also come to affect how the societies are structured and the values people come to adopt. For example, cultural variation in gender roles can arise from the different environments within which people live (Gilmore, 1990). In those cultures where the environment is harsh and requires courage and physical prowess to secure a living (e.g., places where large game is hunted, or risky deep-sea fishing is performed), cultures of masculinity that value the strength and toughness of males are more likely to emerge. For example, on the South Pacific island of Truk, men traditionally had to go on dangerous deep-sea fishing expeditions to obtain food for their families. At the same time, the Trukese greatly value masculinity, demonstrated by young men engaging in frequent, violent drunken fights with knives and clubs.

In contrast, in cultures where the environment is more benign and food is plentiful, androgynous gender roles are more likely to emerge (see Cohen, 2001). For example, men in Tahiti do not hunt; the shallow lagoons provide ample fishing without the need to venture into treacherous waters, and the rich volcanic soils allow for the easy harvesting of taro, cassava, coconuts, and fruit. There is virtually no warfare or feuding in Tahiti, and there is little evidence that masculinity is a matter of much concern for Tahitians.

In general, a survey of the norms for masculinity across diverse ecological contexts led one anthropologist to conclude that “the harsher the environment and the scarcer the resources, the more manhood is stressed as the inspiration and the goal. The correlation could not be more clear, concrete, or compelling” (Gilmore, 1990, p. 224). The physical environments people live in, including features such as the climate, shape the array of possible lifestyles (Van de Vliert, 2008). How much do you think your own culture is the way it is because of your physical surroundings?

PROXIMATE AND DISTAL CAUSES. Small differences can have large effects. Sometimes what might seem to be minor ecological variations can lead to dramatically different cultures, especially as they unfold over time. Consider the following historical event: In 1532, the Spanish explorer Francisco Pizarro, leading a group of 168 soldiers, met with the Incan emperor Atahuallpa in the Peruvian highland town of Cajamarca. At the time, the Incas were the largest and most advanced state in the Americas, and Atahuallpa was surrounded by 80,000 soldiers when Pizarro met with him. Within the day, Pizarro’s men had captured the emperor and killed about 7,000 of his soldiers. In a series of other similarly lopsided battles, Pizarro and his small band of soldiers continued on their rampage, and ultimately the Spaniards conquered the Incan Empire. Jared Diamond, in his Pulitzer Prize–winning book on cultural and geographic variability, Guns, Germs, and Steel (1997), raises some simple yet profound questions about this event. How was it that Pizarro and his vastly outnumbered band of soldiers succeeded in overthrowing the Incan Empire? Why didn’t the Incas defeat Pizarro, or why didn’t the Incas go over to Europe to conquer the Spanish instead?

We can approach these questions by looking at both proximate and distal causes. Proximate causes are those that have a direct and immediate relationship with their effects. At a proximate level, the Spaniards had the political organization that drew on the experiences of thousands of years of written history, along with oceangoing ships that enabled them to reach the Americas. They had steel swords and steel armor, and guns that easily bested the stone clubs, slingshots, and quilt armor of the Incas. The Spaniards also had horses, so they could outmaneuver and overtake the Incas, who were all on foot. In addition, the Incan Empire at the time was divided because of a smallpox epidemic that had been spread across the Americas by the first Spanish explorers, destroying the population. These proximate causes are largely what led to Pizarro’s conquest of Atahuallpa.

But the Spanish advantages over the Incas just push the questions back further. Why did the Spaniards have the technologies, the horses, and the long written history that the Incas didn’t have? Why did the Spanish germs kill the Incas—and not the reverse? To address these questions, we have to consider the distal causes. Distal causes are those initial differences that lead to effects over long time periods, often through indirect relationships. Diamond proposes that two subtle differences in the geography of Eurasia and the Americas are important in helping explain why the Spanish defeated the Incas.

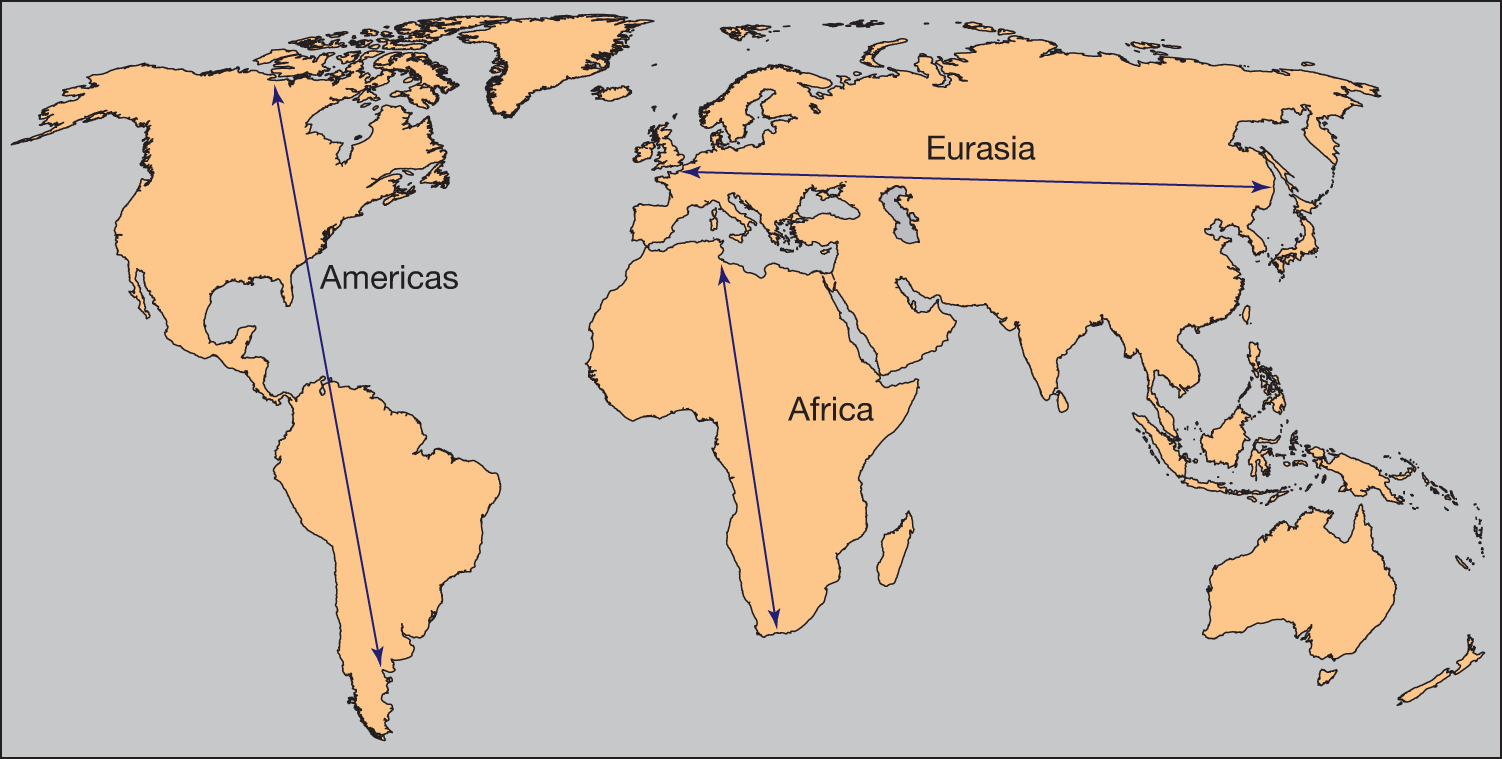

First, in a region known as the Fertile Crescent, which straddled the Middle East from what is now Iran up to Turkey and over to Egypt, there existed a unique collection of plant species (wheat, barley, peas, lentils) and animal species (sheep, goats, pigs, donkeys, cows) that were especially suitable for domestication. These species ultimately provided the basis for the development of Western agriculture. The domesticated species quickly spread both east and west because many populated areas had a similar latitude and climate to the Fertile Crescent. In contrast, agricultural developments by the Mayas in Mexico were unlikely to reach the Incas in Peru because the regions are far apart in terms of latitude and climate. This difference exists because the major continental axis of Eurasia runs east to west, whereas the major continental axes of the Americas and Africa run north to south (Figure 3.2).

Source: Diamond, 1997.

The birth of agriculture enabled these formerly nomadic people to adopt a sedentary lifestyle. In addition, agriculture produced a surplus of food, which enabled some people to spend time on other tasks, including ship building and developing specialized skills, such as metallurgy. Agriculture thus allowed for a more specialized workforce, since it was no longer necessary for everyone to be growing food, and this specialization led to improved tool making. These advances, along with the greater exchange of ideas permitted by the denser populations in Eurasia, led to inventions such as steel, ships, and writing systems, which emerged much earlier there than in the Americas.

Second, the domestication of various animal species in the Fertile Crescent let humans in Eurasia live in close proximity with animals for thousands of years. This caused the spread of diseases that originated in animal species (e.g., measles, tuberculosis, smallpox, and influenza) to humans as well. As the settlements in Eurasia became more densely populated due to the food surplus from agriculture, any contagious diseases would probably spread. Diamond proposes that thousands of years of dense populations living among livestock in Eurasia led to the development of many diseases over the centuries, to which the survivors and their descendants ultimately developed resistances. These diseases would later prove to be deadly when they were introduced in the Americas, where the populations had not developed resistances.

In sum, Diamond proposes that minor geographical differences in the availability of easy-to-domesticate species of plants and animals, and the position of Eurasia, stretching for thousands of miles from east to west along the same latitude and climate, allowed people in Eurasia to develop complex societies, writing systems, tools, weapons, and resistance to deadly germs much earlier than people in other parts of the world. Diamond’s thesis is a powerful argument that cultural differences can originate in geographical differences.

Ways of thinking can also be influenced by geography. Consider this example from China. The two main cereal crops in China are wheat and rice, and they require different cultivation methods. Rice, when cultivated in paddies, is grown in plots of standing water. Rice farming can only be done in areas with sufficient rainfall, and the water must be collected and channeled through irrigation canals to the paddies. The channeling of this shared water source to individual farmers’ respective paddies requires a lot of coordination and cooperation with other families. And rice farming is labor-intensive. In contrast, wheat is grown in fields with typically very little irrigation. A farmer’s family does not have to cooperate as much with neighbors when growing wheat, and relatively less labor is required.

A recent study compared Chinese university students from largely wheat-growing or rice-growing counties (Talhelm et al., 2014). Despite the fact that these different counties were in close proximity (on either side of the Yangtze River, which forms a boundary between the wheat-growing and rice-growing communities), and that the majority of the students were not directly involved in farming themselves, there were pronounced cultural differences in the ways of thinking between these regions. In the rice-growing regions, people showed more evidence of interdependent thinking; they viewed themselves more as part of a network, were more tolerant of nepotism, and engaged in more holistic reasoning (Figure 3.3). (We’ll revisit the nature of interdependent thinking styles in Chapters 6 and 9.)

Source: Figure 1 from T. Talhelm et al. “Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture.” Science 344(6184):603–608. May 2014. Copyright © 2014, American Association for the Advancement of Science. Reprinted with permission from AAAS.

A follow-up study was conducted at several Starbucks locations in rice-growing and wheat-growing regions of China (Talhelm, Zhang, & Oishi, 2018). The researchers assessed how many people were sitting alone, as opposed to sitting with others for coffee. Just as would be predicted by the fact that those in wheat-growing parts of China are less interdependent, people in wheat-growing regions were more likely to be sitting by themselves compared with their counterparts in rice-growing regions. And these regional differences in interdependence are further predicted by variations in wealth. Wealthier regions tend to score lower in interdependence (Takemura, Hamamura, Guan, & Suzuki, 2016), and wealth varies across agricultural regions. The different geographies that allow wheat or rice cultivation are thus distal causes of the ways people currently think.

EVOKED VS. TRANSMITTED CULTURE. There are two other ways of understanding how geography can contribute to cultural variation. Cultural norms can arise as direct responses to features of the environment, or they can arise because of learning from other people. As you’ll soon see, these two different bases of cultural variability are not always clearly separable.

The first way geography can influence cultural norms is through evoked culture. Evoked culture refers to the idea that all people, regardless of where they are from, have a biologically based repertoire of behaviors that are accessible to them, and these behaviors are engaged for appropriate situations (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). For example, all individuals are capable of acting in an intimidating manner when they or their offspring are being threatened. The capacity to act intimidating is universally present; however, it is evoked in certain people only when they find themselves or their loved ones under threat. Some cultural variation can thus be understood as arising from universal psychological tendencies being activated in response to specific conditions.

One example of an evoked cultural difference is cross-cultural variation in habits of conformity. As we’ll discuss later in Chapter 8, while people around the world all feel motivated to conform to the social behavior of others, the conformity motive is stronger in some cultures than others. What accounts for this? One variable that has been examined is the prevalence of pathogens. Environments vary in terms of how hospitable they are to certain kinds of disease-causing organisms, such as those that cause leprosy, malaria, and tuberculosis (Murray & Schaller, 2010). Some regions have had a higher prevalence of pathogens throughout history, and it follows that in those regions people should develop cultural traditions in order to reduce their own personal risk of getting infected. One such tradition would be stronger conformity rates: The more people adhere to strict social norms for food preparation, personal hygiene, interacting with strangers, and protecting water supplies, the lower their risk of infection. Developing strong norms to obey parents and authority figures should help to ensure behaviors that minimize the likelihood of spreading disease.

Researchers have found that the historical prevalence of pathogens in certain regions correlates strongly with the degree to which people in those cultures conform with others (Murray, Trudeau, & Schaller, 2011). These people also have tighter, more rigid adherence to social norms (Gelfand et al., 2011). Although findings like these suggest that all people have the potential to value conformity and strictly observe norms, this motivation is most strongly activated in environments where people face greater risks of being infected by pathogens. Geographical variation—in this case, in terms of pathogen prevalence—differentially evokes universal aspects of human psychology. Evoked culture is thus tied to particular geographical environments: When one moves to new surroundings, new behavioral responses should be evoked.

A second way geography leads to cultural variation is that people come to certain cultural practices through social learning, or by modeling the behavior of others who live near them. This is known as transmitted culture. For example, if you observe your neighbor planting wheat seeds and notice the resulting benefits, you might adopt this cultural practice yourself. The majority of the cultural differences discussed in this book can be best understood in terms of the results of transmitted culture. Although transmitted culture typically begins in a particular geographic area (because we are more likely to learn from those people with whom we interact regularly), it does not necessarily stay bound to a particular location. Unlike evoked culture, transmitted culture can travel with people when they move to new environments. People can bring their transmitted ideas with them, and cultures can spread past their initial set of geographic conditions.

Often, however, the distinction between evoked and transmitted culture is not clear-cut. A particular behavioral script (such as conforming to the way others prepare food) might be activated by a specific situational variable (the prevalence of pathogens). But if that behavioral pattern becomes a norm, that norm might be learned by others, and thus transmitted to future generations. These cultural norms can continue to be transmitted even in contexts where the initial situational variable (the prevalence of pathogens) is no longer present. In fact, it would seem that transmitted culture is always involved in maintaining cultural norms, even when evoked cultural responses are also present (e.g., Norenzayan, 2006).

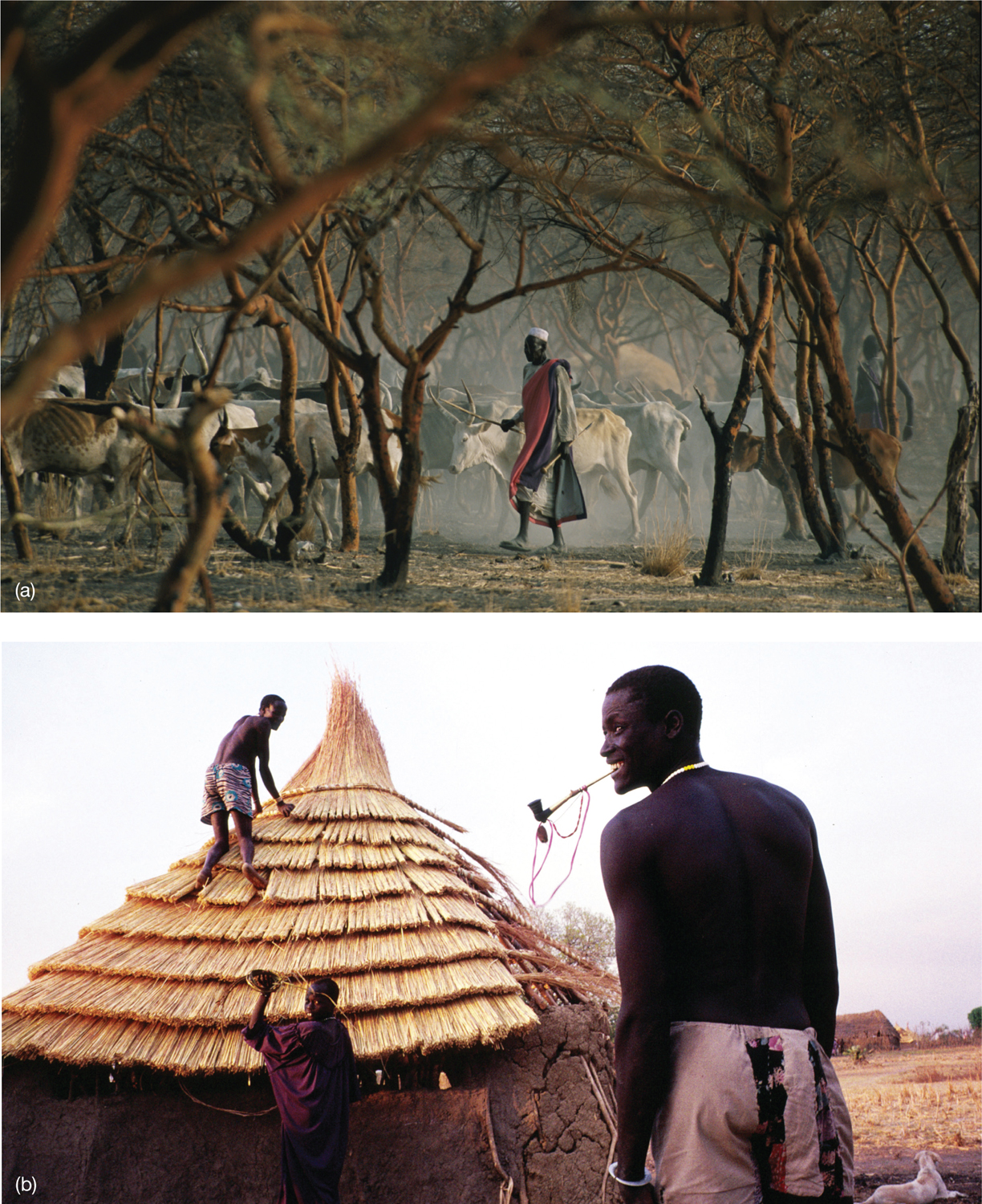

Geographical variation and evoked culture represent important reasons underlying cultural differences. However, there is much more to it. For example, consider two cultures, the Dinka and the Nuer, that coexist in the marshlands of South Sudan (Figure 3.4). These cultures have coexisted in the same region for more than a century, and they both live a migratory existence in which they grow millet and corn in the wet season and move about to let their cattle graze in the dry season. However, despite the fact that people from these two cultures live in the same environments, share a similar technology, raise similar crops and livestock, and are descended from the same ancestors from about a thousand years ago, their cultures are different in a number of pronounced ways. The Nuer maintain larger herds of cattle and rely largely on milk from their herds, whereas the Dinka regularly slaughter their herds and rely on the meat. The Dinka tribal memberships are based on who lives next to whom in the wet season, whereas the Nuer base kinship on the male line. In addition, the Nuer tribes are far larger and more militarily powerful than the Dinka. The Nuer also have very costly and inflexible dowry payments that are incurred when daughters are married, whereas the Dinka have small and flexible payments. The same geographic location can, therefore, result in quite different cultural practices (see Richerson & Boyd, 2005, for a review).

Likewise, the limits of geographical variation on culture are evident in a landmark study by American anthropologist Robert Edgerton (1971). Edgerton studied four East African tribes (the Sebei, Pokot, Kamba, and Hehe), each of which had multiple communities living in different settings. For example, some communities from all four of the tribes lived in moist highlands where they subsisted largely through farming, whereas other communities from each of the four tribes lived in dry lowlands where they subsisted mostly through herding. Edgerton contrasted the attitudes of these various communities. If people’s attitudes are generally a product of their environment, then the communities that farmed should show attitudes that are largely similar and should appear different from the communities that herded. In contrast, if people’s attitudes are mostly the product of transmitted culture, then the different communities within each tribe should show attitudes that are quite similar to each other, and different from the attitudes of the other tribes, regardless of whether they lived in farming regions or herding regions. Edgerton found that for the majority of attitudes, tribal affiliation was a better predictor of attitudes than was the primary means of subsistence (see Richerson & Boyd, 2005, for a review). Again, these findings demonstrate that although environment is a key component of cultural variation, much cultural variation is transmitted in ways that are largely independent of geographic location.

Here’s a thought experiment to illustrate how transmitted culture tends to be of more importance than evoked culture (see Boyd, Richerson, & Henrich, 2011). Imagine you’re left to survive alone on King William Island, located far to the north in the Canadian Arctic. To make the challenge easier, you’re provided with various kinds of equipment and supplies that will last you for a year, so you’ll have time to become familiar with your new surroundings before having to eke it out on your own. Do you think you’d be able to figure out how to survive?

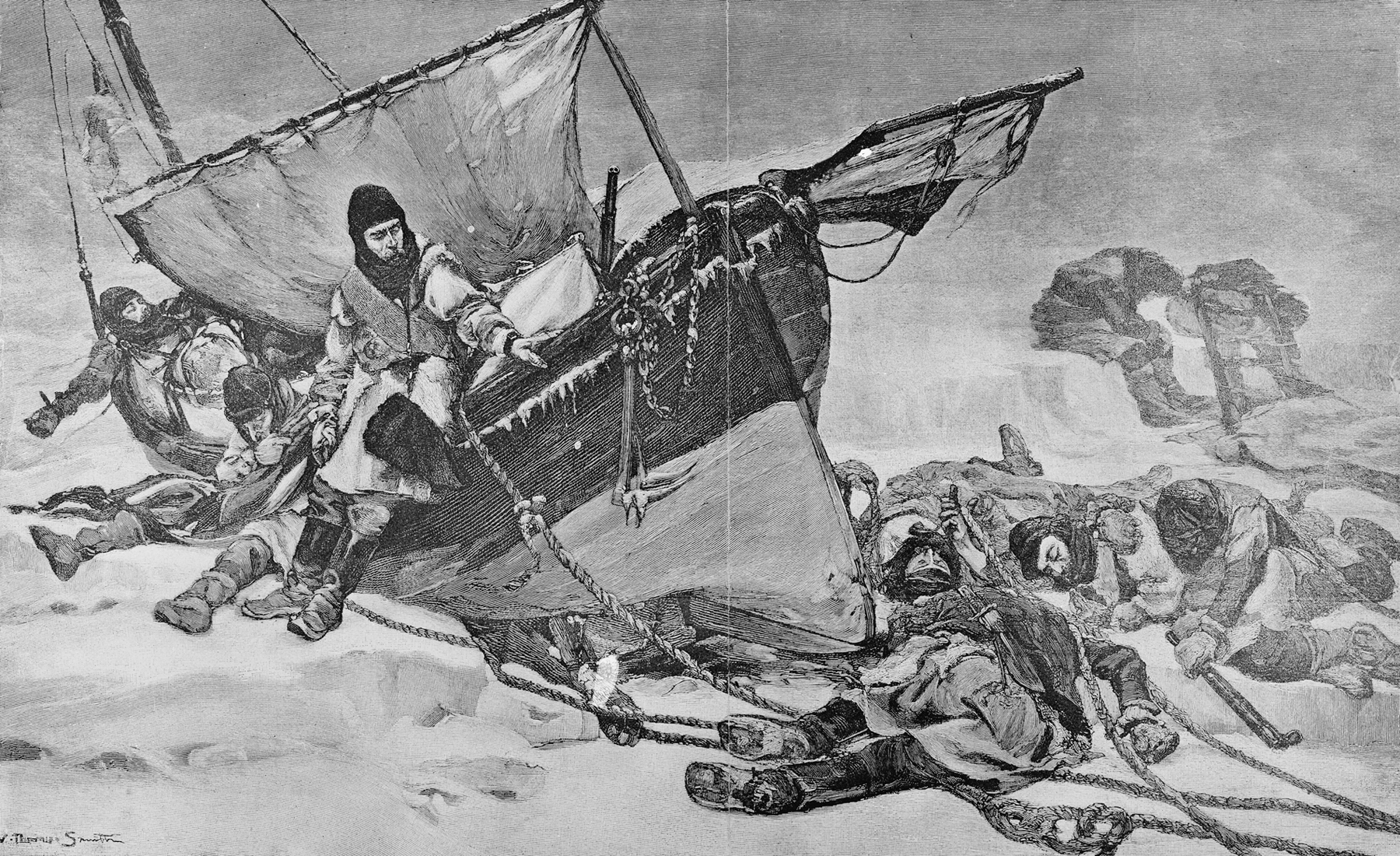

I’m sorry to say I think most likely you would fail. You see, this experiment has already been conducted. In 1845 Captain Sir John Franklin departed from England on an expedition to discover the Northwest Passage, a northern route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It was the best-equipped expedition in the history of British polar exploration. Franklin’s ships ran aground near King William Island, and the 128 men were left to fend for themselves as they awaited help (Figure 3.5). Two years later, after their supplies had all run out, hypothermia, scurvy, and starvation (which ultimately led to cannibalism among the survivors) killed the last of the remaining crew members. It’s not surprising that the men were unable to survive in such a hostile environment—except for the fact that King William Island was home to numerous settlements of Netsilik, an Inuit group, who have been living in the area for thousands of years. The Netsilik have coped with the hostile environment just fine, using only the supplies and tools they were able to fashion from local materials.

If evoked culture were the primary determinant of people’s repertoire of behaviors, we would expect that the same hostile environment would have evoked the same survival responses in Franklin’s crew as the Netsilik. But we can see that the behaviors transmitted over generations of Netsilik have provided them with the means to survive in this environment, whereas the accumulated cultural knowledge of 19th-century Britons was not suited for long-term survival in the Canadian Arctic. Interestingly, the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen spent 2 years on King William Island in 1903–1904, and he and his men survived just fine; they had sought out the nearby Netsilik and learned from them how to hunt seals, make fur clothing, and acquire other survival skills. The key for survival on King William Island rested on cumulative cultural ideas about how to subsist and survive in the hostile environment. These essential ideas were only available through transmitted culture, which the unfortunate members of the Franklin expedition did not have. (For other examples of the plight of lost European explorers who don’t learn local ways, see Henrich, 2016.)

Understanding cultural variability thus requires us to look at both the evoked culture that originates in the surrounding environment and the transmitted culture that spreads the norms that develop. An important question to consider, then, is why some ideas are transmitted yet others are not.

Glossary

- proximate cause

- A cause that has a direct and immediate relationship with its effects. See also distal cause.

- distal cause

- An initial difference that leads to effects over long periods of time, often through an indirect relationship. See also proximate cause.

- evoked culture

- The idea that all people, regardless of where they are from, have a biologically based repertoire of behaviors that are accessible to them, and that these behaviors are engaged for appropriate situations. See also transmitted culture.

- transmitted culture

- The idea that people find out about certain cultural practices through social learning, or by modeling the behavior of others who live near them. See also evoked culture.