1.1 |

The Nature of Science |

You probably asked a lot of questions when you were a child: What is that? How does it work? Why does it do that? We are driven by a deep-seated curiosity about the world around us, a tendency to ask questions that we seem to express most freely when we are children (FIGURE 1.2). Through the centuries, that spirit of inquiry has been the main driving force behind science.

FIGURE 1.2 Curiosity Is at the Heart of Scientific Inquiry

Do you recall any questions about nature that you asked when you were little?

Beyond the universal thirst for understanding, science offers many practical benefits. Technology refers to the practical application of scientific techniques and principles. Science is behind technologies like satellites and the TV receivers that use them, lifesaving medical procedures and drugs, microwave ovens, and every text, tweet, and image we send over the Internet. But beyond being a provider of technologies, science is a way of understanding the world.

The scientific way of looking at the world—let’s call it scientific thinking—is logical, strives for objectivity, and values evidence over all other ways of discovering the truth. Scientific thinking is one of the most democratic of human endeavors because it is not owned by any group, tribe, or nation, nor is it presided over by any human authority that is elevated above ordinary humans.

People like you are contributing to the advance of science

In recent years, hundreds of Citizen Science projects have been undertaken. In these projects, people from all walks of life partner with professional researchers to advance scientific knowledge (TABLE 1.1). Citizen scientists have volunteered their DNA, tracked bees, recorded the blooming and fruiting of local plants, monitored invasive species, cataloged roadkills, donated their gaming skills to help predict protein structure, or simply loaned the computing capacity of their workstations to scientists over the Internet.

|

| TABLE 1.1 |

Citizen Science Projects: Collaborations between Citizens and Professional Scientists |

scroll to view

Crowdsourcing—using the services of the online community to create content and solve problems—has made large contributions to understanding genetic variation in humans.

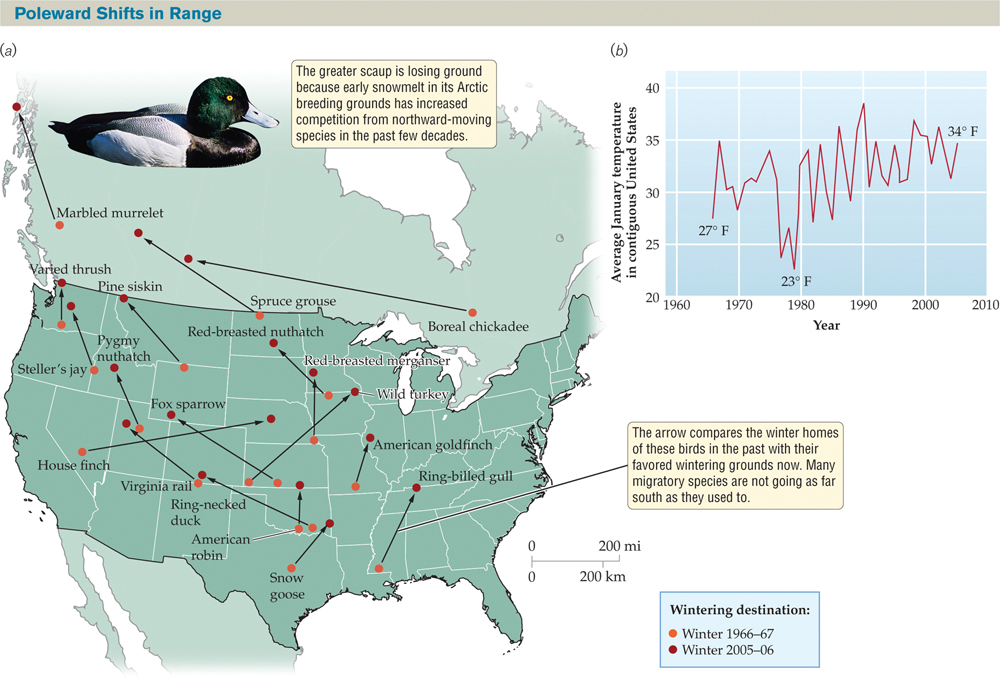

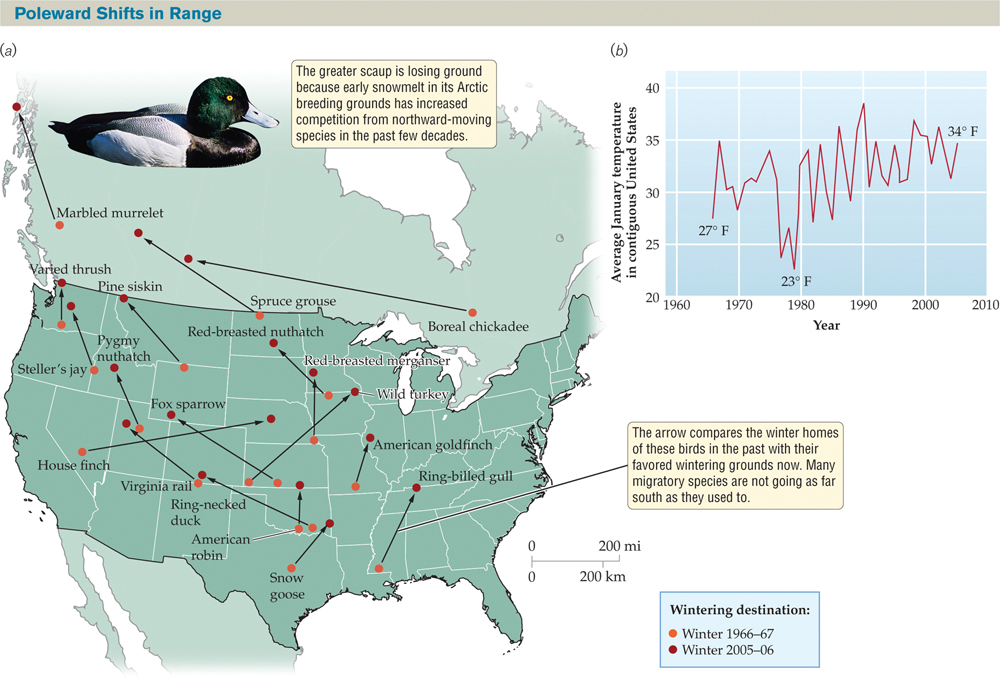

The Christmas Bird Count, organized by the National Audubon Society since 1900, is the longest-running Citizen Science project. Data gathered by hundreds of thousands of volunteers have contributed to over 200 technical papers and helped scientists understand how climate change is affecting bird migration (FIGURE 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3 The Winter Range of Many Migratory Birds Has Shifted Northward

This range map (a) is based on data collected by volunteers participating in the Christmas Bird Count, the longest-running Citizen Science project. It shows that many migratory birds in North America are not going as far south in the nonbreeding season as they did just 40 years ago. The graph (b) shows the change in average January temperature in the United States over the same period. Globally, the average surface temperature of Earth has increased by about 1°C in the last 100 years—a phenomenon known as global warming.

Science is a body of knowledge and a process for generating that knowledge

Science takes its name from scientia, a Latin word for “knowledge.” Science is a particular kind of knowledge, one that deals with the natural world. By “natural world” we mean the observable universe around us—that which can be seen or measured or detected in some way by humans. We can define science as a body of knowledge about the natural world and an evidence-based process for acquiring that knowledge (TABLE 1.2).

|

| TABLE 1.2 |

Characteristics of Science |

scroll to view

As implied in the definition, science is much more than a mountain of knowledge. Science is a particular system for generating knowledge. The processes that generate scientific knowledge have traditionally been called the scientific method, a label that originated with nineteenth-century philosophers of science. Although “method” is singular, the scientific method is not one single sequence of steps or a set recipe that all scientists follow in a rigid manner. Instead, the term represents the core logic of how science works. Some people prefer to speak of the “process of science,” rather than the scientific method. Whatever we call it, the procedures that generate scientific knowledge can be applied in a broad range of disciplines—from social psychology to forensics.

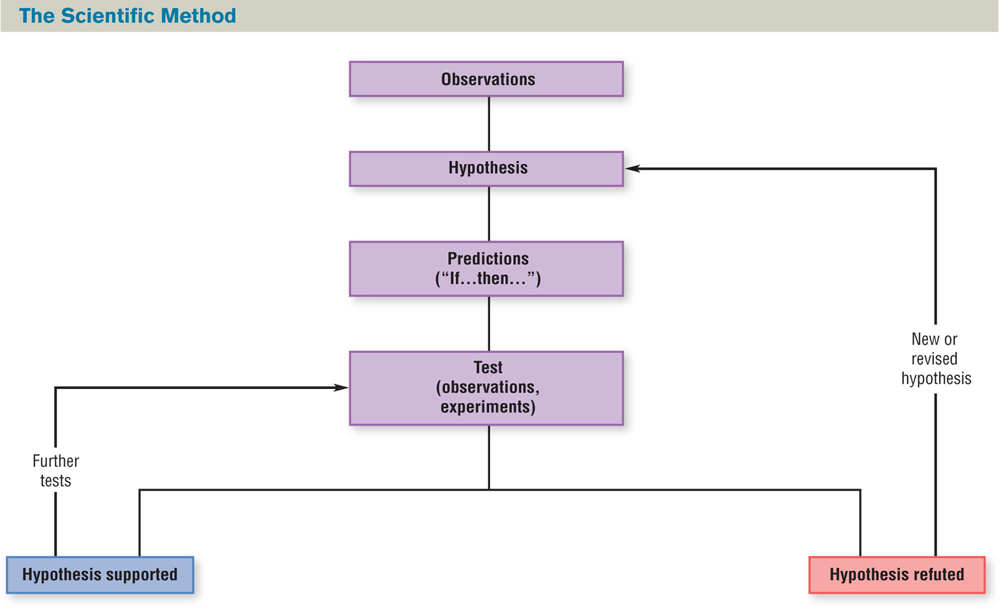

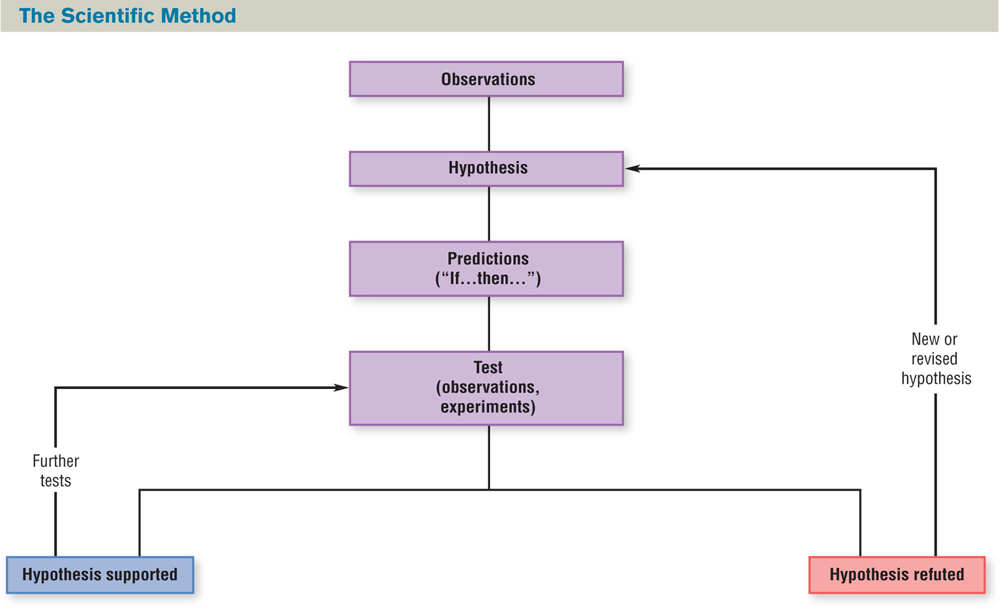

The scientific method can be illustrated in a concept map like the one in FIGURE 1.4. A concept map is a diagram illustrating how the components of a particular structure, organization, or process relate to each other. Concept maps help us visualize how parts fit together and flow from one another. Keep this in mind as we explore the process of science in this chapter.

FIGURE 1.4 Scientific Hypotheses Must Be Testable

Scientific hypotheses must be testable

A scientific hypothesis (plural “hypotheses”) is an educated guess that seeks to explain observations of nature. In science, a hypothesis is useless unless it is testable. The tests could be observational studies or experiments or both. Who conducts these tests? No matter how creative and plausible the hypothesis is, the burden of testing it rests on the person proposing the hypothesis.

When a hypothesis is tested and upheld, it is said to be supported. A supported hypothesis is one in which we can be relatively confident. If the tests show the hypothesis to be wrong, then the hypothesis has been refuted (shown to be false). Sometimes a test neither supports nor refutes a hypothesis, in which case the test is declared inconclusive and the investigators must find a better test.

The scientific method requires objectivity

An absolute requirement of the scientific method is that evidence must be based on observations or experiments or both. Furthermore, the observations and experiments that furnish the evidence must be subject to testing by others; independent researchers should be able to make the same observations, or obtain the same experimental results if they use the same conditions. In addition, the evidence must be collected in an objective fashion—that is, as free of bias as possible. As you might imagine, freedom from bias is more an ideal than something we can depend on. However, modern science has safeguards in place to ensure that scientific knowledge will come closer to meeting that ideal over time.

The main protection against bias, and even outright fraud, is the requirement for peer-reviewed publication. Claims of evidence that are confined to a scientist’s notebook or the blogosphere do not meet the criterion of peer-reviewed publication. A peer is someone at an equal level—in this case, another scientist who is recognized as expert in the field. Peer-reviewed publications are scientific journals that publish original research only after it has passed the scrutiny of experts who have no direct involvement in the research under review (FIGURE 1.5).

FIGURE 1.5 Some Peer-Reviewed Science Journals

The criterion of peer-reviewed publication is one means of enforcing rigor and objectivity in the application of the scientific method.