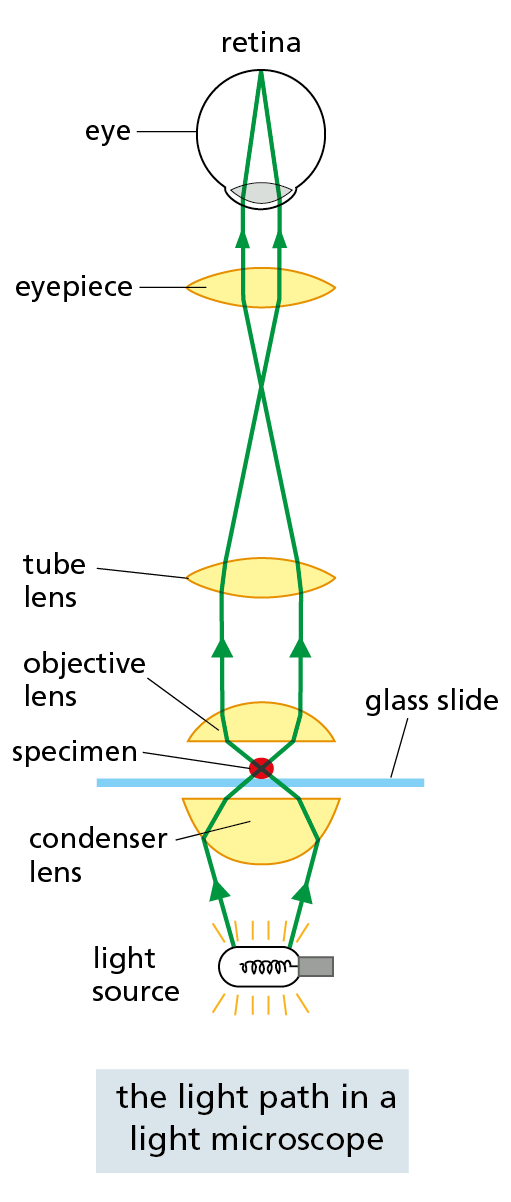

CONVENTIONAL LIGHT MICROSCOPY

Courtesy of Andrew Davis.

A conventional light microscope allows us to magnify cells up to 1000 times and to resolve details as small as 0.2 μm (200 nm), a limitation imposed by the wavelike nature of light, not by the quality of the lenses. Three things are required for viewing cells in a light microscope. First, a bright light must be focused onto the specimen by lenses in the condenser. Second, the specimen must be carefully prepared to allow light to pass through it. Third, an appropriate set of lenses (objective, tube, and eyepiece) must be arranged to focus an image of the specimen in the eye.

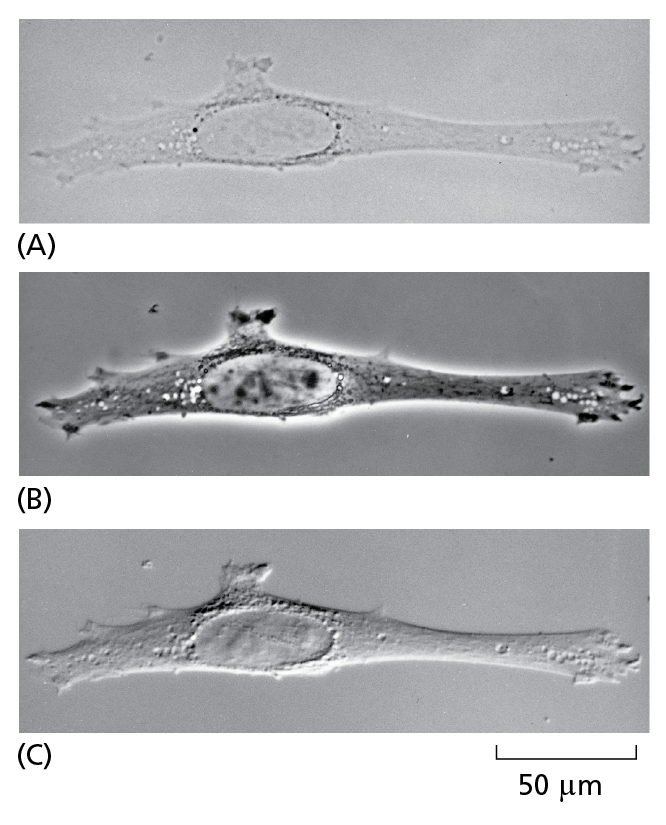

LOOKING AT LIVING CELLS

The same unstained, living animal cell (fibroblast) in culture viewed with

(A) the simplest, brightfield optics;

(B) phase-contrast optics;

(C) interference-contrast optics.

The two latter systems exploit differences in the way light travels through regions of the cell with differing refractive indices. All three images can be obtained on the same microscope simply by interchanging optical components.

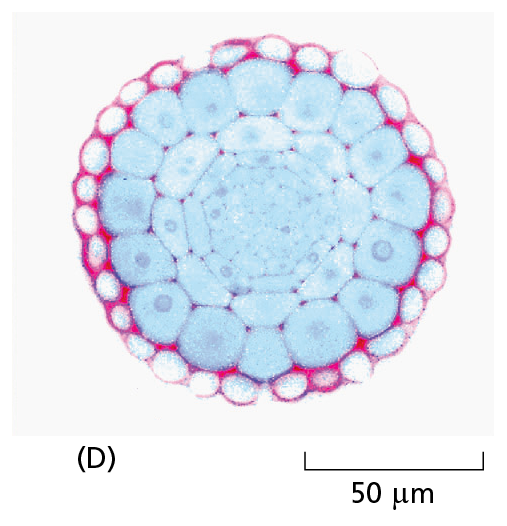

FIXED SAMPLES

Courtesy of Catherine Kidner.

Most tissues are neither small enough nor transparent enough to examine directly in the microscope. Typically, therefore, they are chemically fixed and cut into thin slices, or sections, that can be mounted on a glass microscope slide and subsequently stained to reveal different components of the cells. A stained section of a plant root tip is shown here (D).

FLUORESCENCE MICROSCOPY

Fluorescent dyes used for staining cells are detected with the aid of a fluorescence microscope. This is similar to an ordinary light microscope, except that the illuminating light is passed through two sets of filters (yellow). The first (1) filters the light before it reaches the specimen, passing only those wavelengths that excite the particular fluorescent dye. The second (2) blocks out this light and passes only those wavelengths emitted when the dye fluoresces. Dyed objects show up in bright color on a dark background.

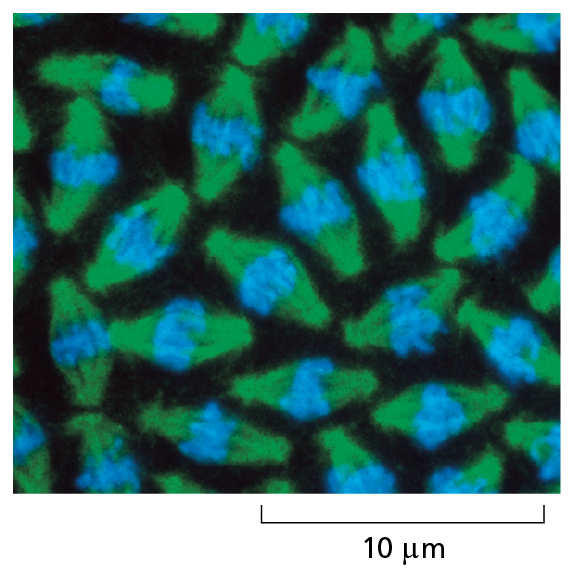

FLUORESCENT PROBES

Courtesy of William Sullivan.

Fluorescent molecules absorb light at one wavelength and emit it at another, longer wavelength. Some fluorescent dyes bind specifically to particular molecules in cells and can reveal their location when the cells are examined with a fluorescence microscope. In these dividing nuclei in a fly embryo, the stain for DNA fluoresces blue. Other dyes can be coupled to antibody molecules, which then serve as highly specific staining reagents that bind selectively to particular molecules, showing their distribution in the cell. Because fluorescent dyes emit light, they allow objects even smaller than 0.2 μm to be seen. Here, a microtubule protein in the mitotic spindle (see Figure 1–28) is stained green with a fluorescent antibody.

CONFOCAL FLUORESCENCE MICROSCOPY

Courtesy of Stefan Hell.

A confocal microscope is a specialized type of fluorescence microscope that builds up an image by scanning the specimen with a laser beam. The beam is focused onto a single point at a specific depth in the specimen, and a pinhole aperture in the detector allows only fluorescence emitted from this same point to be included in the image. Scanning the beam across the specimen generates a sharp image of the plane of focus—an optical section. A series of optical sections at different depths allows a three-dimensional image to be constructed, such as this highly branched mitochondrion in a living yeast cell.

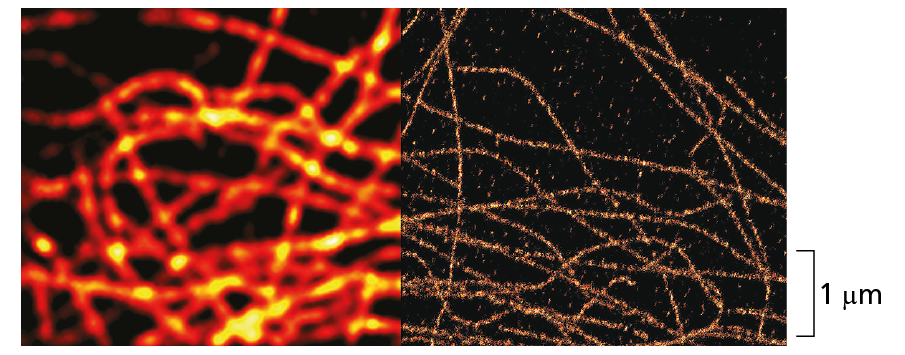

SUPER-RESOLUTION FLUORESCENCE MICROSCOPY

Several recent and ingenious techniques have allowed fluorescence microscopes to break the usual resolution limit of 200 nm. One such technique uses a sample that is labeled with molecules whose fluorescence can be reversibly switched on and off by different colored lasers. The specimen is scanned by a nested set of two laser beams, in which the central beam excites fluorescence in a very small spot of the sample, while a second beam—wrapped around the first—switches off fluorescence in the surrounding area. A related approach allows the positions of individual fluorescent molecules to be accurately mapped while others nearby are switched off. Both approaches slowly build up an image with a resolution as low as 20 nm. These new super-resolution methods are being extended into 3-D imaging and real-time live cell imaging.

Courtesy of Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC.

Microtubules viewed with conventional fluorescence microscope (left) and with super-resolution optics (right). In the super-resolution image, the microtubule can be clearly seen at the actual size, which is only 25 nm in diameter.

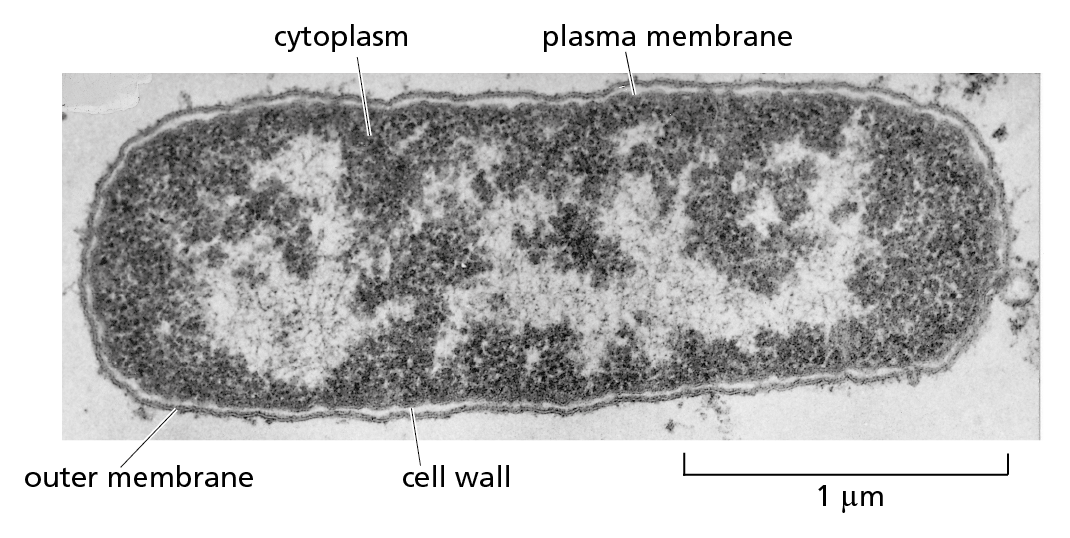

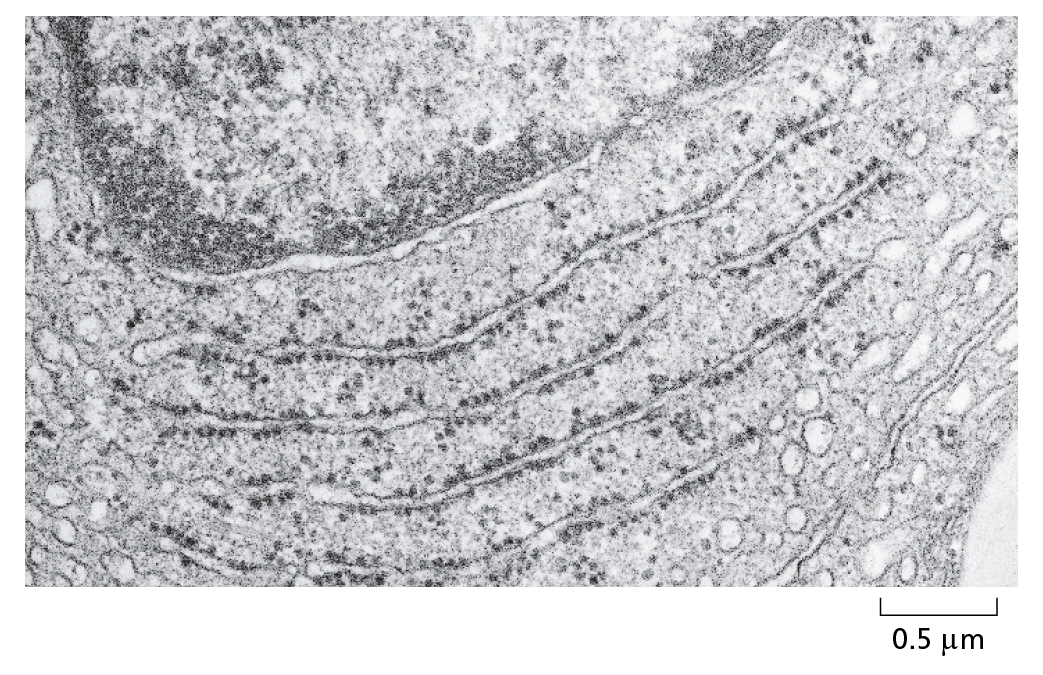

TRANSMISSION ELECTRON MICROSCOPY

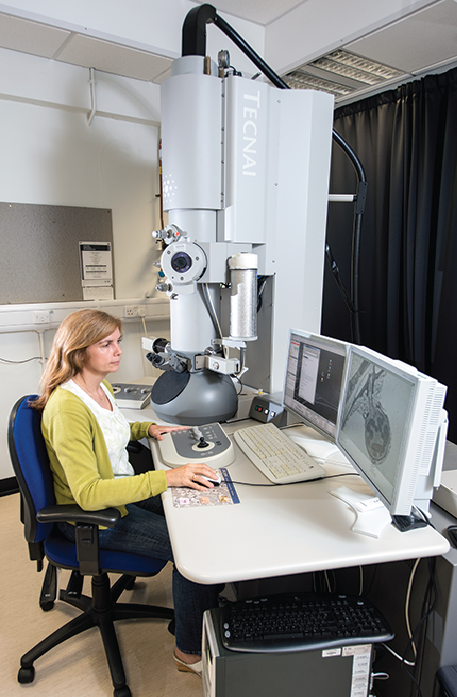

Courtesy of Andrew Davis.

The electron micrograph below shows a small region of a cell in a thin section of testis. The tissue has been chemically fixed, embedded in plastic, and cut into very thin sections that have then been stained with salts of uranium and lead.

Courtesy of Daniel S. Friend.

The transmission electron microscope (TEM) is in principle similar to a light microscope, but it uses a beam of electrons, whose wavelength is very short, instead of a beam of light, and magnetic coils to focus the beam instead of glass lenses. Because of the very small wavelength of electrons, the specimen must be very thin. Contrast is usually introduced by staining the specimen with electron-dense heavy metals. The specimen is then placed in a vacuum in the microscope. The TEM has a useful magnification of up to a million-fold and can resolve details as small as about 1 nm in biological specimens.

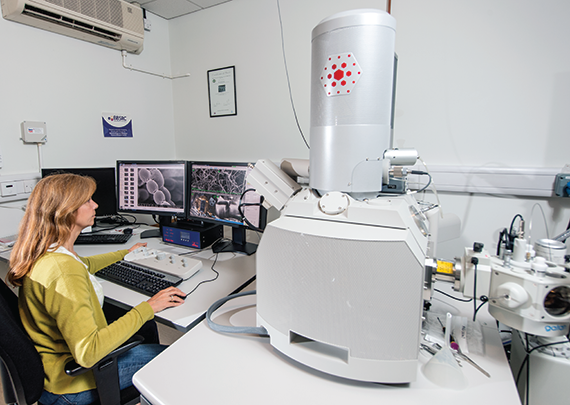

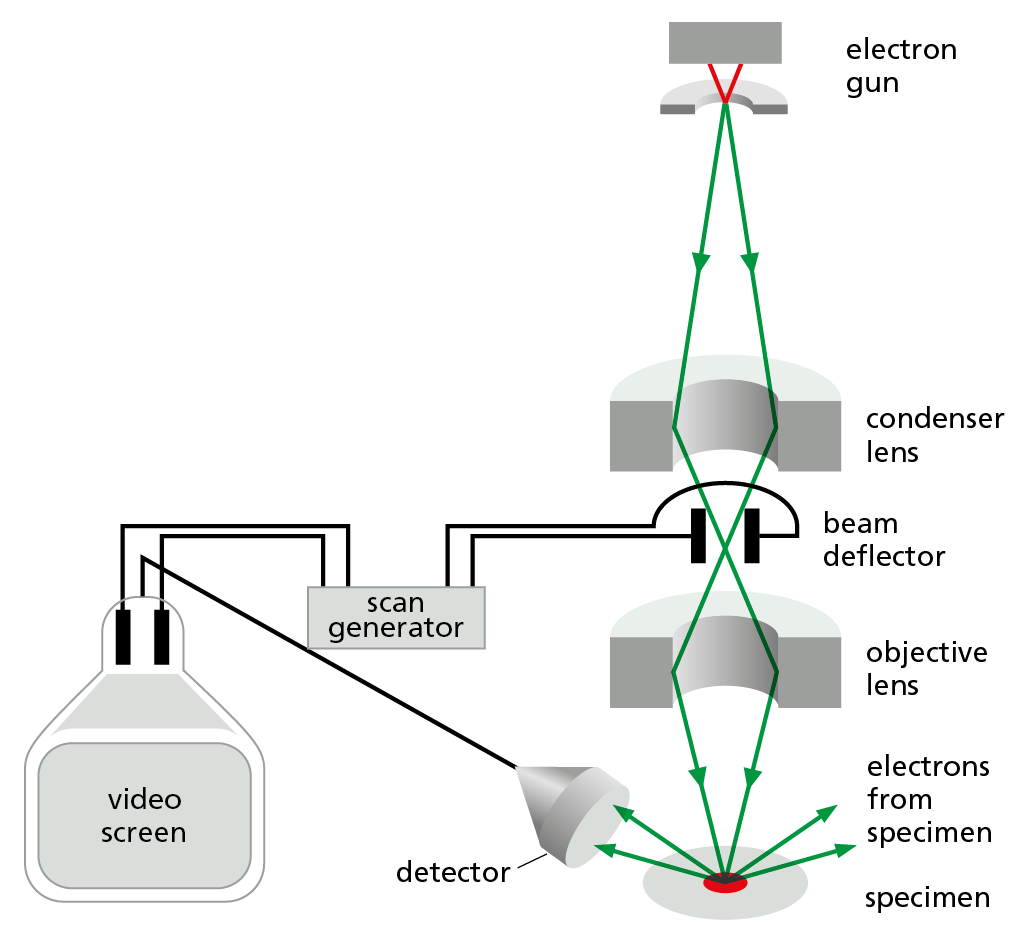

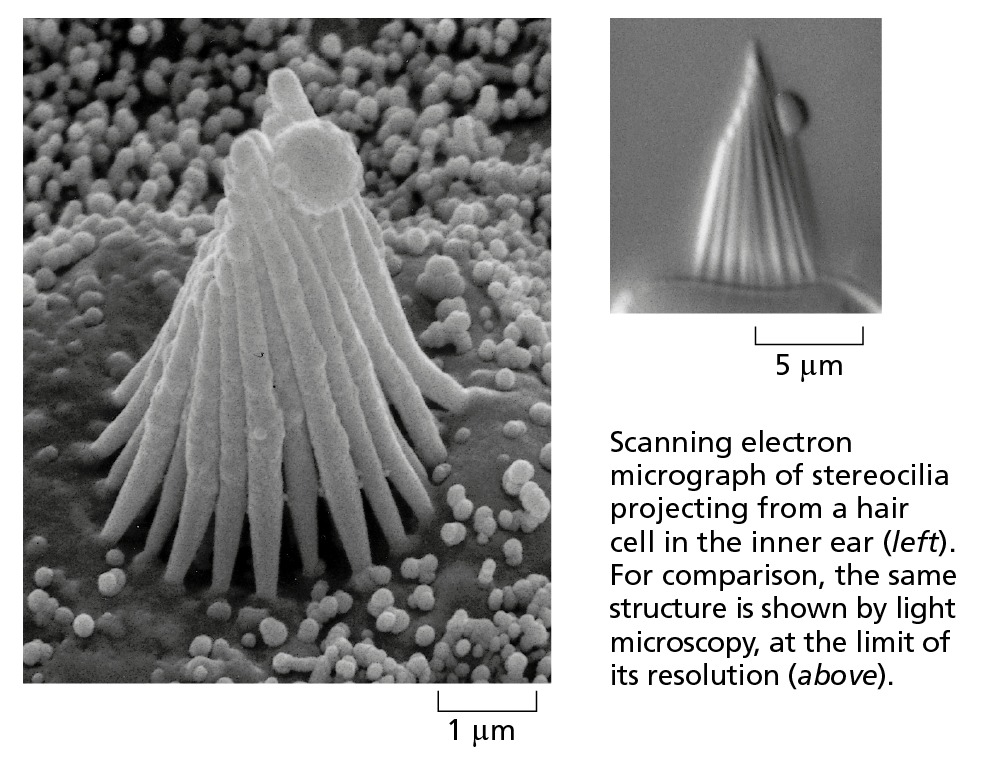

SCANNING ELECTRON MICROSCOPY

Courtesy of Andrew Davis.

In the scanning electron microscope (SEM), the specimen, which has been coated with a very thin film of a heavy metal, is scanned by a beam of electrons brought to a focus on the specimen by magnetic coils that act as lenses. The quantity of electrons scattered or emitted as the beam bombards each successive point on the surface of the specimen is measured by the detector, and is used to control the intensity of successive points in an image built up on a video screen. The microscope creates striking images of three-dimensional objects with great depth of focus and can resolve details down to somewhere between 3 nm and 20 nm, depending on the instrument.

Courtesy of Richard Jacobs and James Hudspeth.