QUESTION 1–5

Suggest a reason why it might have been advantageous for eukaryotic cells to have evolved elaborate internal membrane systems that allow them to import substances from the outside, as shown in Figure 1–26.

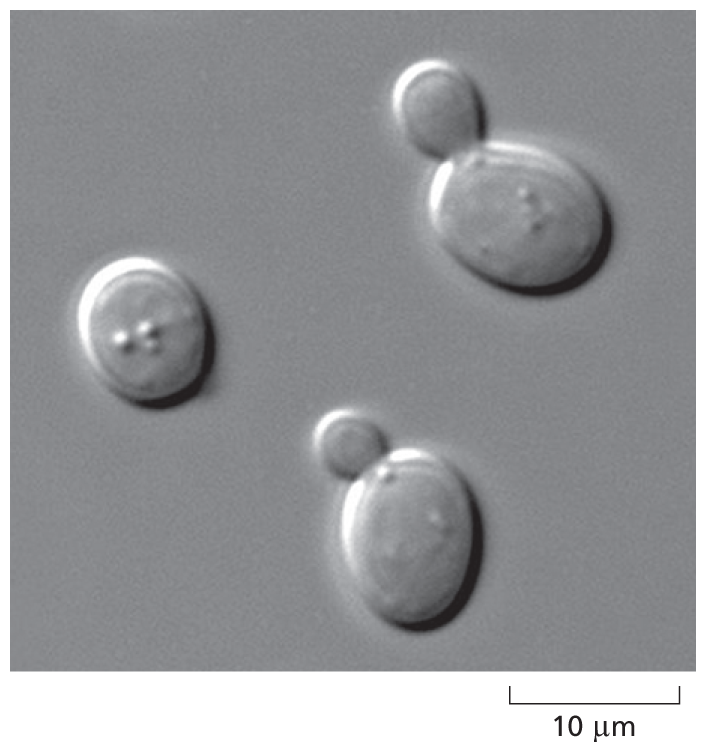

Eukaryotic cells are typically 1000 to 10,000 times larger in volume than most bacteria and archaea. Although some live independent lives as single-celled organisms, such as amoebae and yeasts (Figure 1–16), others live in multicellular assemblies. As we have seen, all of the more complex multicellular organisms—including plants, animals, and fungi such as mushrooms—are formed from eukaryotic cells.

A micrograph shows Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The structure shows three ovoid shaped cells. Two of them have a smaller cell budding out of it. The larger cells are about 8 micrometers in diameter. Shown on a scale of 10 micrometers.

Figure 1–16 Yeasts are simple, free-living eukaryotes. The cells shown in this micrograph belong to the species of yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, used to make dough rise and turn malted barley juice into beer. As can be seen in this image, the cells reproduce by growing a bud and then dividing asymmetrically into a large mother cell and a small daughter cell; for this reason, they are called budding yeast.

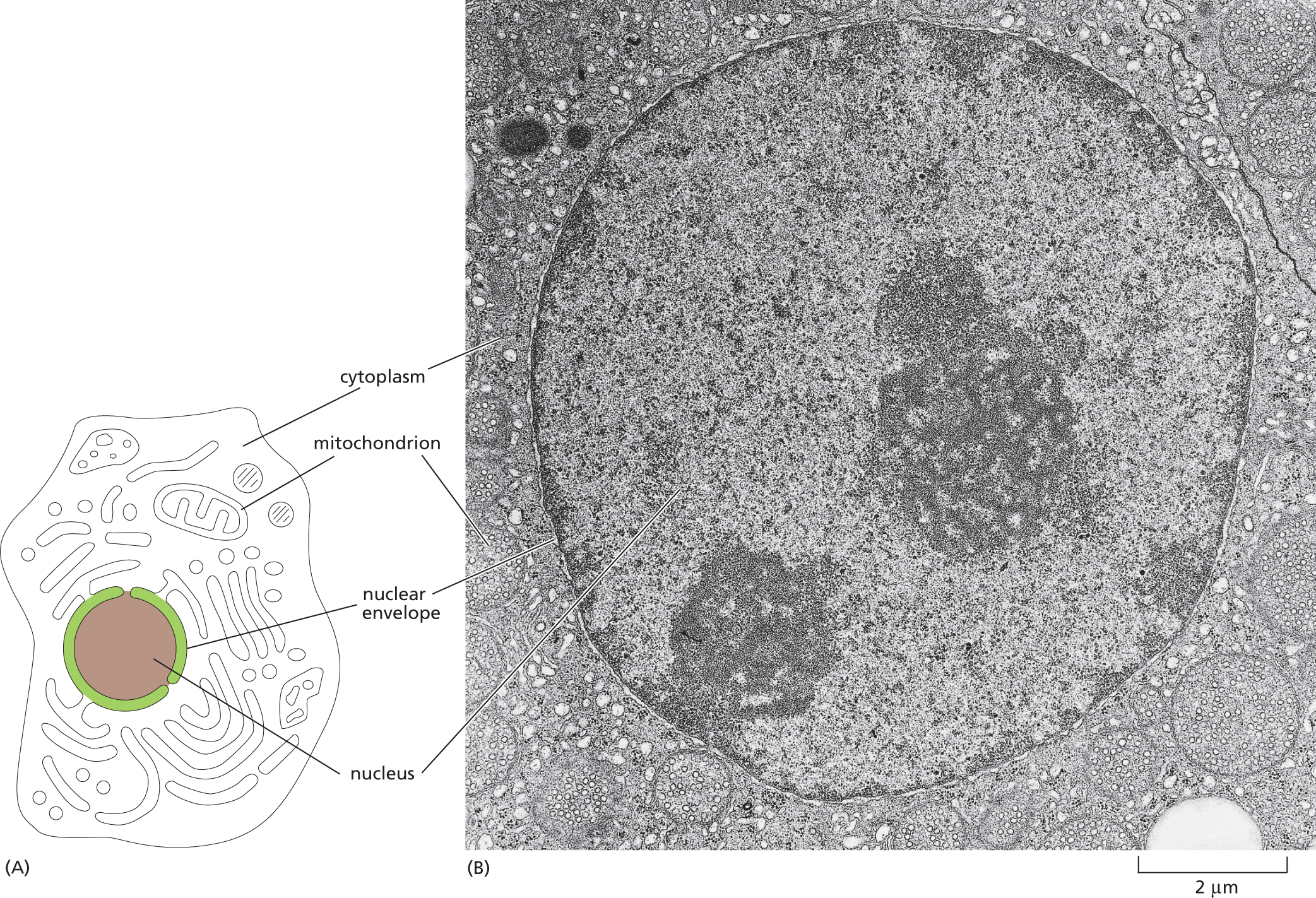

By definition, all eukaryotic cells have a nucleus. But possession of a nucleus goes hand-in-hand with possession of a variety of other organelles, most of which are membrane-enclosed and common to all eukaryotic organisms but absent in prokaryotes. In this section, we take a look at the main organelles found in eukaryotic cells from the point of view of their functions, and we consider how they came to serve the roles they have in the life of the eukaryotic cell. Unraveling the roles these organelles play in the life of a eukaryotic cell is one of the crowning achievements of biological exploration, and it laid the foundation for understanding the biology of our own cells—and how these systems become impaired by aging and disease.

The nucleus is typically the most prominent organelle in a eukaryotic cell (Figure 1–17). It is enclosed within two concentric membranes that form the nuclear envelope, and it contains molecules of DNA—extremely long polymers that encode the genetic information of the organism. In the light microscope, these giant DNA molecules become visible as individual chromosomes when they become more compact before a cell divides into two daughter cells (Figure 1–18). Bacteria and archaea also store their genetic information in the form of DNA; however, these cells do not keep their DNA corralled inside a nuclear envelope, segregated from the rest of the cell contents.

Schematic A shows an animal cell and micrograph B shows the nucleus of a mammalian cell, approximately 10 micrometers in diameter. The cell in the schematic contains a nucleus in the center of the cell, which is circular in shape. The nucleus is enclosed by a double walled membrane labeled nuclear envelope. The region outside the nucleus is labeled as cytoplasm. The cell also contains a double membrane organelle labeled mitochondrion. Micrograph B shows an enlarged view of a mammalian nucleus. The inner region of the nucleus has tiny granules and two distinct patches. A thin boundary around the nucleus is labeled nuclear envelope. The region outside the nucleus is labeled cytoplasm. An organelle, which is roughly oval in shape, is labeled mitochondrion.

Figure 1–17 The nucleus contains most of the DNA in a eukaryotic cell. (A) This drawing of a typical animal cell shows its extensive system of membrane-enclosed organelles. The nucleus is colored brown, the nuclear envelope is green, and the cytoplasm (the interior of the cell outside the nucleus) is white. (B) An electron micrograph of the nucleus in a mammalian cell. Individual chromosomes are not visible because at this stage of the cell-division cycle, the DNA molecules are dispersed as fine threads throughout the nucleus. (B, by permission of E.L. Bearer and Daniel S. Friend.)

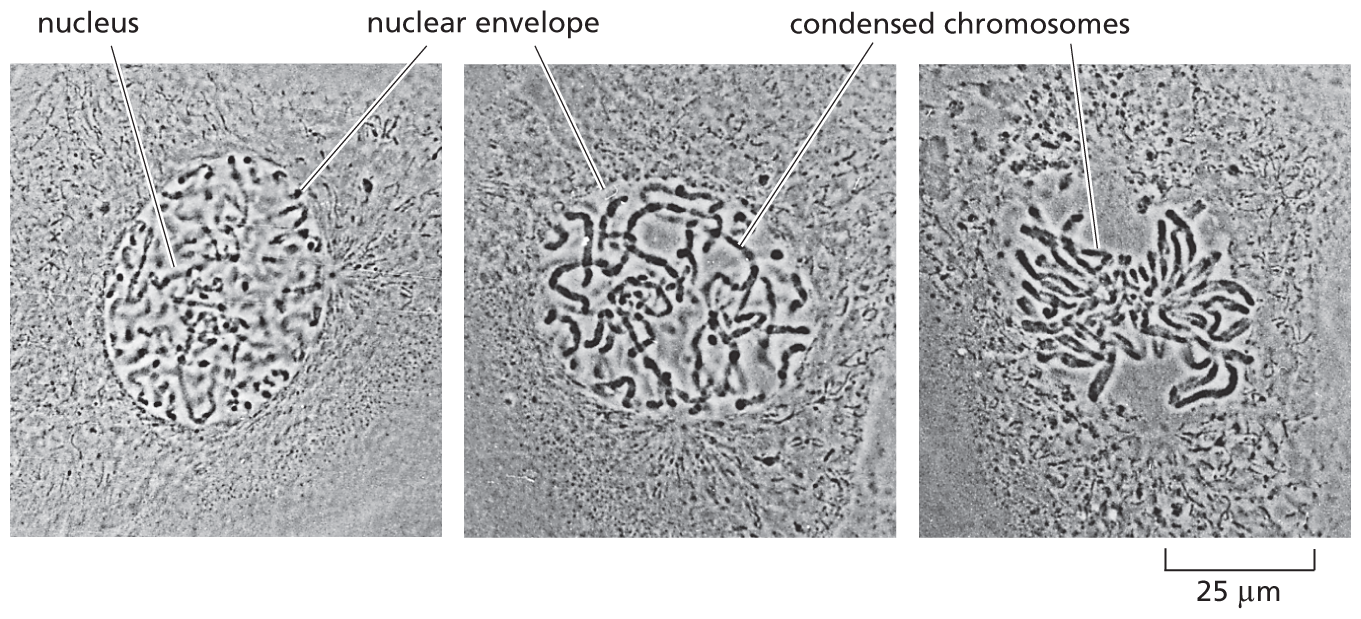

Three micrographs depict the condensation of chromosomes during cell division. The first panel shows a rounded nucleus with a nuclear envelope. The second panel shows condensed chromosomes inside the nuclear envelope. The third panel shows the chromosomes segmented into the divided portions of the cell with no nuclear envelope.

Figure 1–18 Chromosomes become visible when a cell is about to divide. As a eukaryotic cell prepares to divide, its DNA molecules become progressively more compacted (condensed), forming wormlike chromosomes that can be distinguished in the light microscope (see also Figure 1–5). The photographs here show three successive steps in this chromosome condensation process in a cultured cell from a newt’s lung; note that in the last micrograph on the right, the nuclear envelope has broken down in preparation for the chromosomes to move into position for cell division. (Courtesy of Conly L. Rieder, Albany, New York.) (Dynamic Figure) In an early fly embryo (below), nuclei divide without accompanying cell division, producing a cell that has thousands of nuclei. These nuclei divide synchronously, their chromosomes (green) condensing and being pulled into daughter nuclei by a cytoskeletal machine (red) called the mitotic spindle. (Courtesy of William Sullivan.) For another view of the mitotic spindle, see Figure 1–29.

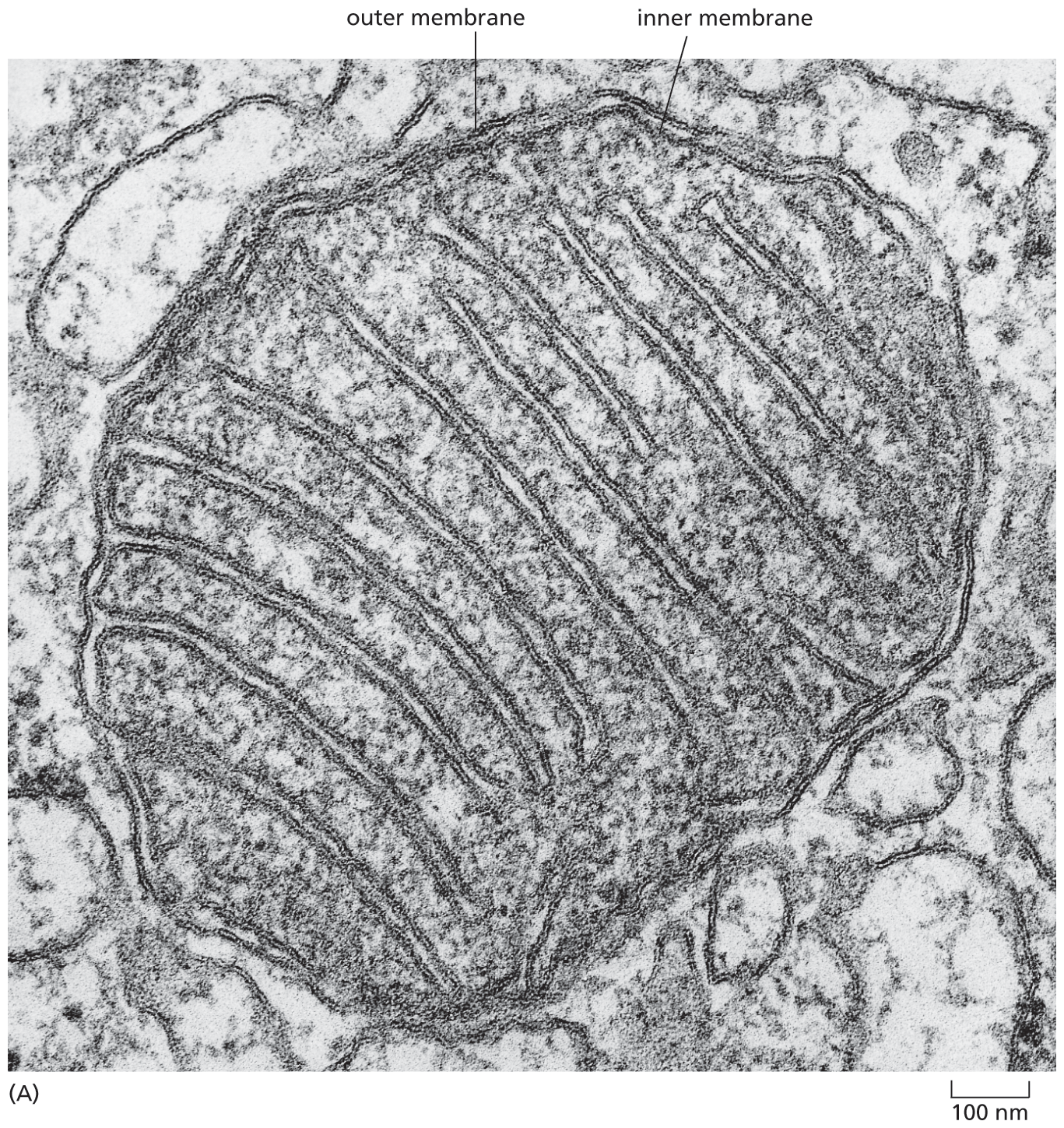

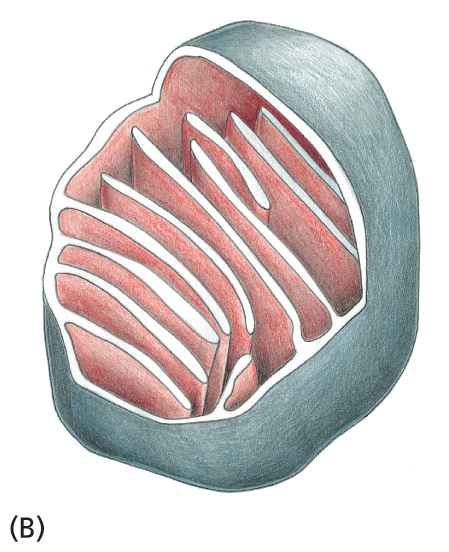

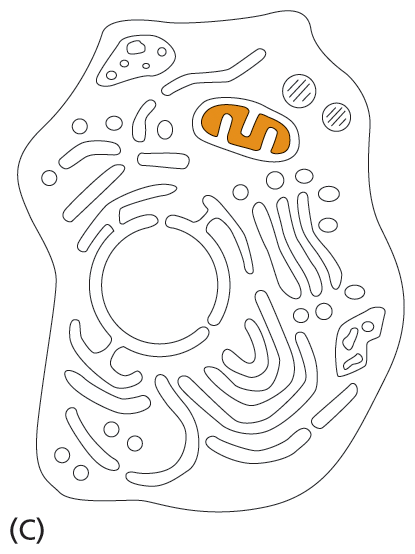

Mitochondria (singular, mitochondrion) are present in essentially all eukaryotic cells, and they are among the most conspicuous organelles present in the cytoplasm (see Figure 1–8B). When seen with an electron microscope, individual mitochondria are found to be enclosed in two separate membranes, with the inner membrane formed into folds that project into the interior of the organelle (Figure 1–19).

A micrograph depicts the structure of a mitochondrion with a diameter of approximately 1 micrometer. The cross section of mitochondria includes an inner membrane and outer membrane. which form a maze like structure inside the organelle.

Schematic B shows the outer membrane of the mitochondria and a section of the highly convoluted inner membrane.

Schematic C shows a cell, with its various components of which mitochondria is highlighted.

Microscopic examination by itself, however, gives little indication of what mitochondria actually do for the cell. Their function was discovered by breaking open cells and then spinning the soup of cell fragments in a centrifuge; this treatment separates organelles and other subcellular structures according to their size and density. Purified mitochondria were then tested to see what chemical processes they could perform. This approach revealed that mitochondria are generators of chemical energy for the cell. They harness the energy from the oxidation of food molecules, such as sugars, to produce adenosine triphosphate, or ATP—the basic chemical fuel that powers most of the cell’s activities. Because the mitochondrion consumes oxygen and releases CO2 in the course of this activity, the entire process is called cell respiration—essentially, breathing at the level of the cell. Without mitochondria, eukaryotes such as animals, fungi, and plants would be unable to use oxygen to extract the energy they need from the food molecules that nourish them, a process we consider in detail in Chapter 14.

Mitochondria contain their own DNA and reproduce by dividing. Their strong resemblance—both in appearance and in DNA sequence—to modern-day bacteria provides persuasive evidence that mitochondria evolved from an aerobic bacterium that was engulfed by an anaerobic ancestor of present-day eukaryotic cells. This event created a symbiotic relationship that provided both partner cells with metabolic support, enabling them to survive and reproduce. The observations of the Asgard archaeon in close association with its prokaryotic partner cells strongly suggest that the original capturing cell was an archaeon (Figure 1–20).

An illustration demonstrates the process of an archaeon engulfing a bacteria. There are three stages. In the first stage, there is archaeon D N A at the center of the archaeon. The archaeon had narrow surface protrusions and wider expanded protrusions. Two of the expanded protrusions surround a bacterial ectosymbiont. The process leading to the second stage is labeled enclosure of ectosymbiont by archaeal membrane fusion. The second stage shows the bacterial endosymbiont completely inside an expanded protrusion. All the protrusions are larger than they were in the first stage. The process leading to the third stage is labeled escape of endosymbiont into cytosol and formation of new intracellular compartments. The third stage shows the bacterial endosymbiont is not a precursor of a mitochondrion. Other part of the archaeon membrane are forming the endoplasmic reticulum and nuclear envelope. This final stage is a precursor to an aerobic eukaryote.

Figure 1–20 Mitochondria are thought to have evolved from engulfed bacteria. It is extremely likely that mitochondria evolved from aerobic bacteria that were captured and subsequently engulfed by an ancient, anaerobic archaeal cell. According to this model, the surface protrusions of an ancient, Asgard-like archaeon expanded and surrounded an aerobic bacterium, fostering a symbiotic relationship between the two cells. Over time, the expanded protrusions fused with one another, trapping the bacterium as an endosymbiont within the body of the archaeon, where it initially remained enclosed by an internal membrane derived from the archaeal plasma membrane. At some point, the symbiont escaped from this archaeal membrane and entered the cell’s cytosol, where it eventually evolved into a mitochondrion containing DNA and surrounding membranes derived from the engulfed bacterium. As indicated, the archaeal plasma membrane that folded inward during the process of protrusion, expansion, and fusion is proposed to have formed both the nuclear envelope and the internal membrane-enclosed organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum. (Adapted from H. Imachi et al., Nature 577:519–525, 2020 and from D.A. Baum and B. Baum, BMC Biol. 12:76–92, 2014.)

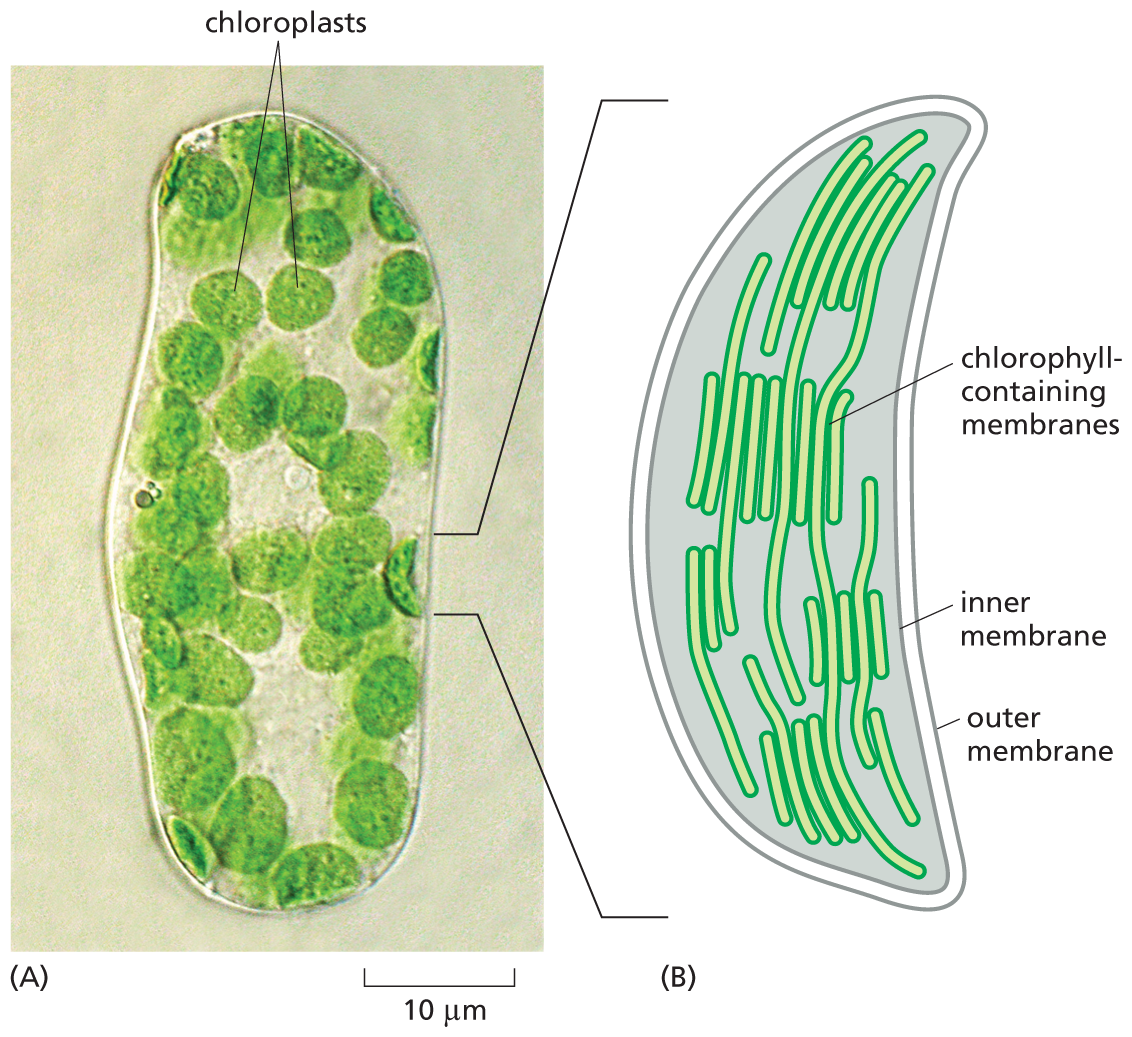

Chloroplasts are large, green organelles that are found in the cells of plants and algae, but not in the cells of animals or fungi. These organelles have an even more complex structure than mitochondria: in addition to their two surrounding membranes, they possess internal stacks of membranes containing the green pigment chlorophyll (Figure 1–21).

Micrograph A shows a leaf cell with chloroplasts. Schematic B shows a chloroplast. The micrograph shows several circular shaped structures labeled chloroplasts inside an oval shaped cell, on a scale of 10 micrometers. The schematic shows an enlarged view of a chloroplast with an inner and outer membrane; long filament like structures extending from the top to bottom of the chloroplast are labeled chlorophyll containing membranes.

Figure 1–21 Chloroplasts in plant cells capture the energy of sunlight. (A) Seen in this light micrograph, a single cell isolated from a leaf of a flowering plant has many green chloroplasts. (B) A drawing of a single chloroplast, showing the inner and outer membranes, as well as the highly folded system of internal membranes containing the green chlorophyll molecules that absorb light energy. (A, courtesy of Preeti Dahiya.)

Chloroplasts carry out photosynthesis—trapping the energy of sunlight in their chlorophyll molecules and using this energy to drive the manufacture of energy-rich sugar molecules. In the process, they release oxygen as a molecular by-product. Plant cells can later extract this stored chemical energy when they need it, just as animal cells do: by oxidizing these sugars and their breakdown products, mainly in the mitochondria. Chloroplasts thus enable plants to get their energy directly from sunlight. They also allow plants to produce the food molecules—and the oxygen—that mitochondria use to generate chemical energy in the form of ATP. How these organelles work together is discussed in Chapter 14.

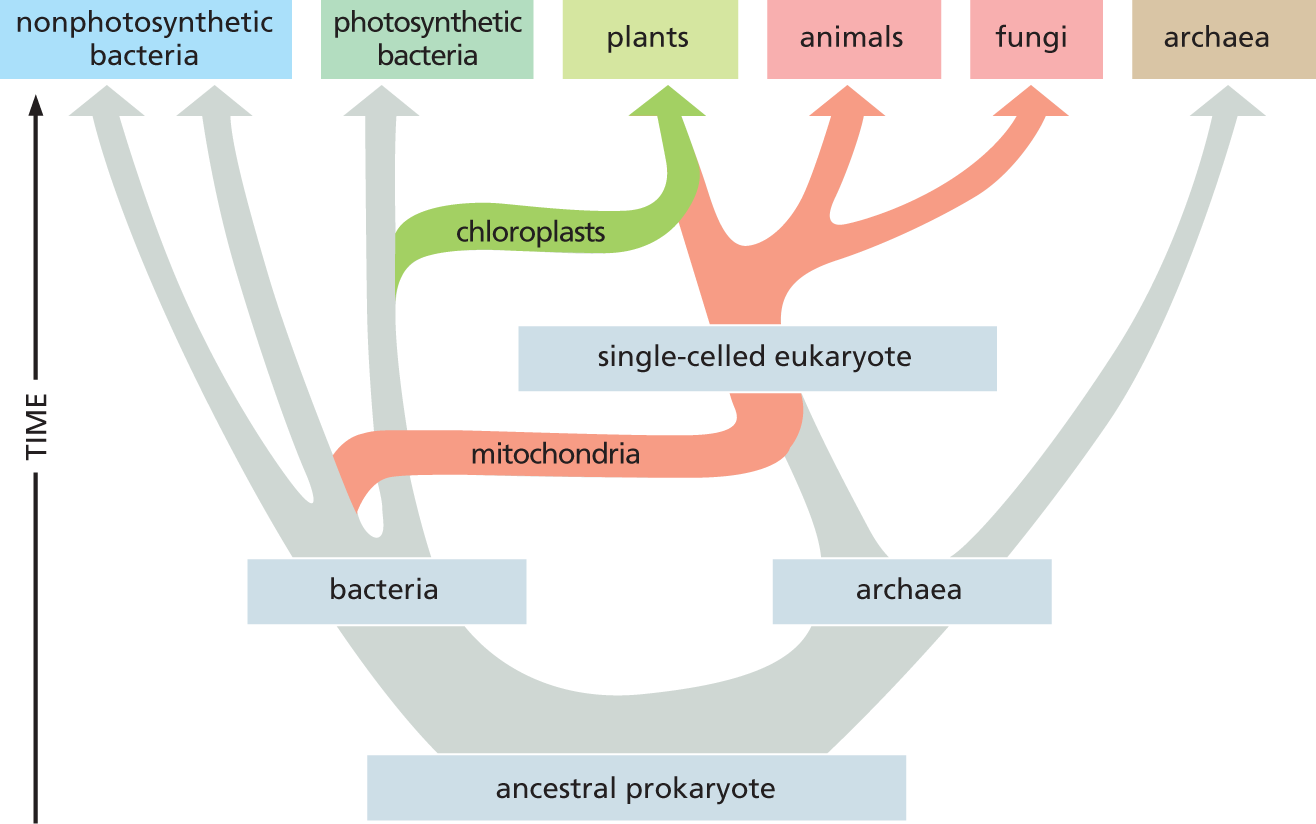

Like mitochondria, chloroplasts contain their own DNA, reproduce by dividing in two, and are thought to have evolved from bacteria—in this case, from photosynthetic bacteria that were engulfed by eukaryotic-like cells that had already acquired mitochondria (Figure 1–22).

A chart shows the evolution of eukaryotes. The ancestral prokaryote diverges into bacteria and archaea. The bacteria diverges into non photosynthetic bacteria and photosynthetic bacteria. A portion of archaea forms a single-celled eukaryote by acquiring mitochondria from bacteria and diverges into animals and fungi. Later a portion of single-celled eukaryote acquires chloroplasts and forms plants.

Figure 1–22 Eukaryotes contain a combination of genomes that originally derived from archaea and bacteria. The bacterial and archaean lineages diverged from one another very early in the evolution of life on Earth. Some time later, archaeal cells are thought to have acquired mitochondria by establishing symbiotic relationships with aerobic bacteria; later still, a subset of these single-celled eukaryotes acquired chloroplasts. Mitochondria are essentially the same in plants, animals, and fungi, and therefore were presumably acquired before these lines diverged about 1.5 billion years ago.

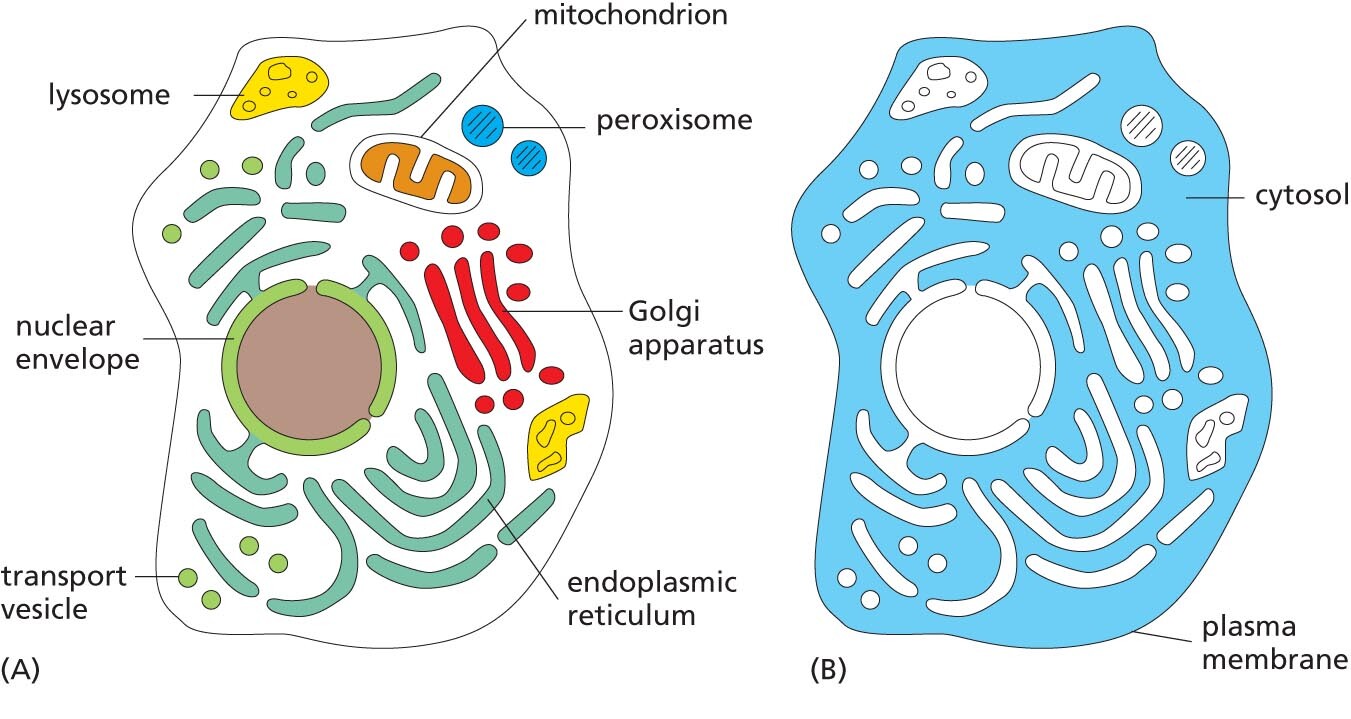

Nuclei, mitochondria, and chloroplasts are not the only membrane-enclosed organelles inside eukaryotic cells. The cytoplasm contains a profusion of other organelles that are surrounded by single membranes (see Figure 1–8A). Most of these structures are involved with the cell’s ability to import raw materials and to export both useful substances and waste products that are produced by the cell (a topic we discuss in detail in Chapter 12).

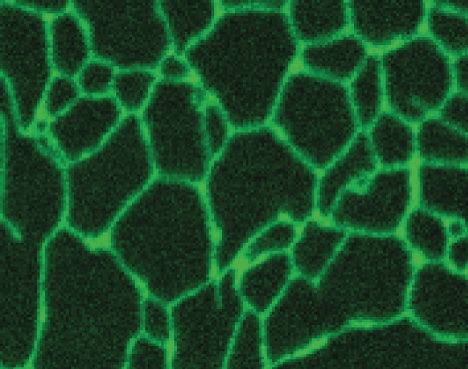

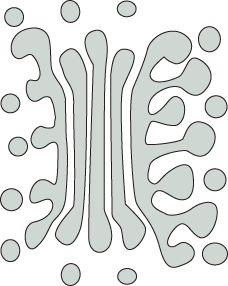

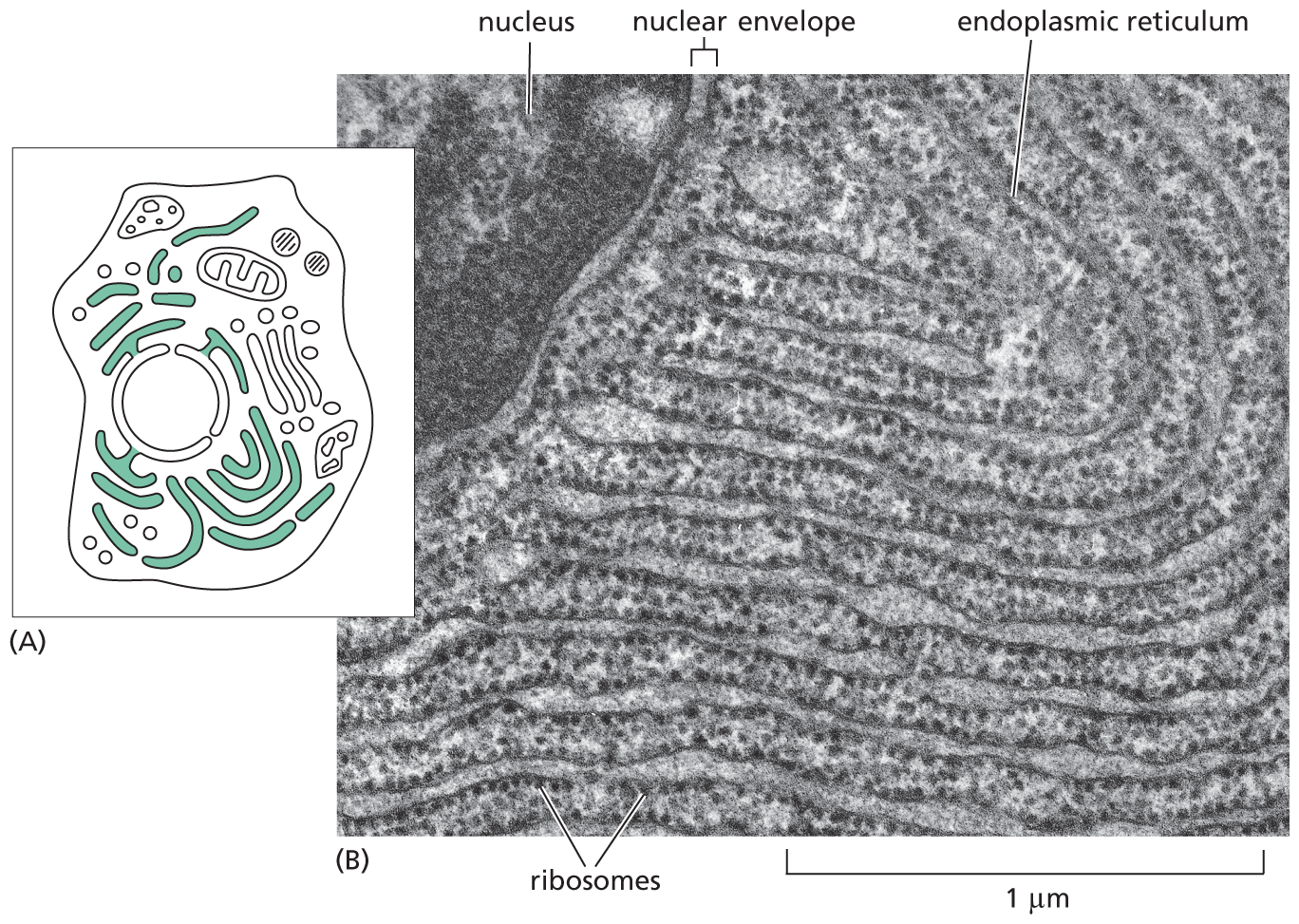

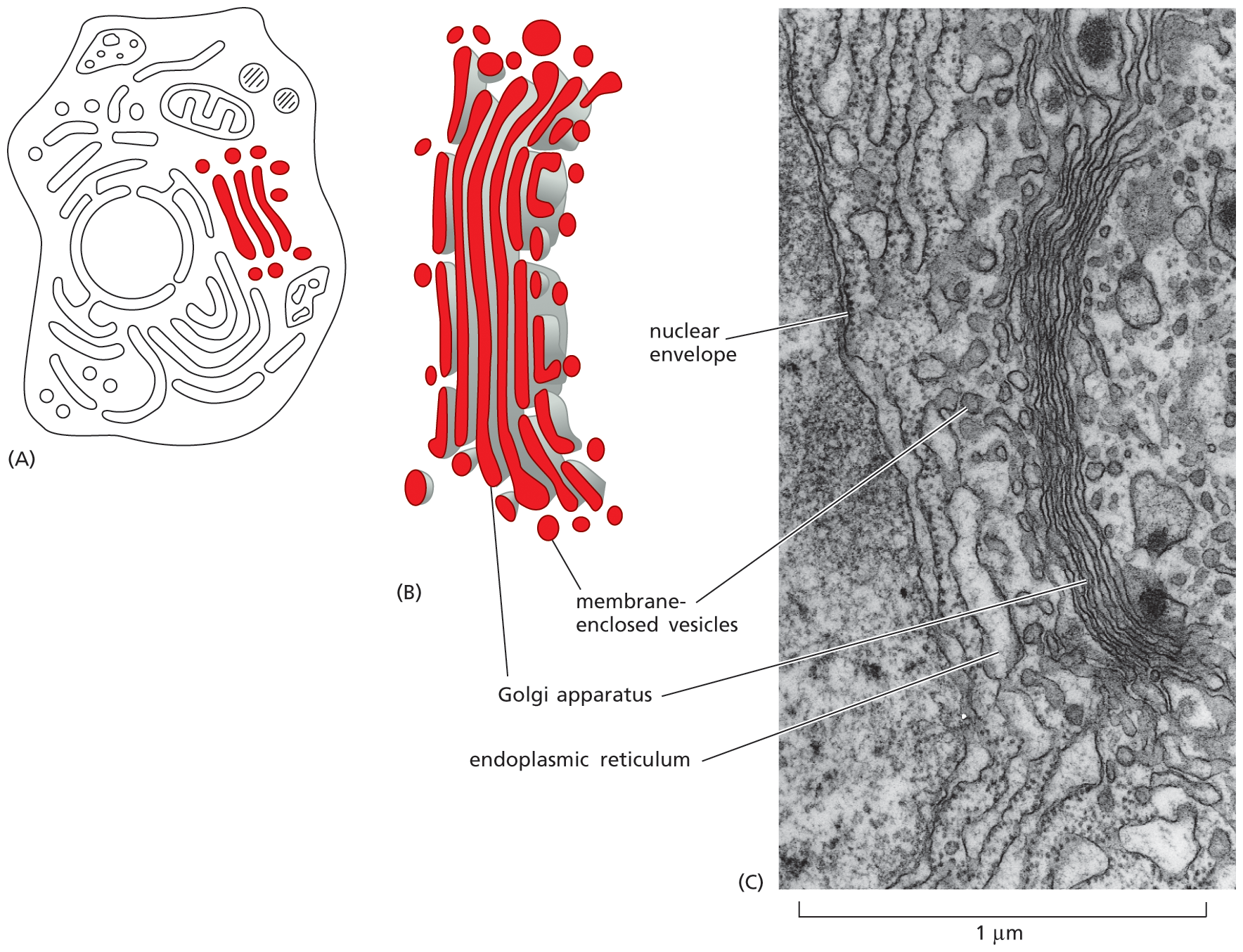

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an irregular maze of interconnected spaces enclosed by a membrane (Figure 1–23). It is the site where most cell-membrane components, as well as materials destined for export from the cell, are made. This organelle is especially extensive in cells that are specialized to secrete large amounts of protein. Stacks of flattened, membrane-enclosed sacs constitute the Golgi apparatus (Figure 1–24), which modifies and packages molecules made in the ER that are destined to be either secreted from the cell or transported to another cell compartment. Lysosomes are small, irregularly shaped organelles in which intracellular digestion occurs, releasing nutrients from ingested food particles into the cytosol and breaking down unwanted molecules for either recycling within the cell or excretion from the cell. Indeed, many of the large and small molecules within the cell are constantly being broken down and remade. Peroxisomes are small, membrane-enclosed vesicles that provide a sequestered environment for a variety of reactions in which hydrogen peroxide is used to inactivate toxic molecules. Membranes also form many types of small transport vesicles that ferry materials between one membrane-enclosed organelle and another. All of these membrane-enclosed organelles are highlighted in Figure 1–25A.

Schematic A shows an animal cell with the endoplasmic reticulum highlighted within. The endoplasmic reticulum is spread throughout the cell. Micrograph B shows a section of the nucleus, nuclear envelope, and an enlarged view of the endoplasmic reticulum (E R) with ribosomes studded on it, next to the nuclear envelope. The scale reads, 1 micrometer. The endoplasmic reticulum has many layers.

Figure 1–23 The endoplasmic reticulum produces many of the components of a eukaryotic cell. (A) Schematic diagram of an animal cell shows the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in green. (B) Electron micrograph of a thin section of a mammalian pancreatic cell, which is specialized for protein secretion, shows a small part of the ER, which is vast in this cell type. Note that the ER is continuous with the membranes of the nuclear envelope. The black particles studding the region of the ER (and nuclear envelope) shown here are ribosomes, structures that translate RNAs into proteins. Because of its appearance, ribosome-coated ER is often called “rough ER” to distinguish it from the “smooth ER,” which does not have ribosomes bound to it. (B, courtesy of Lelio Orci.)

Schematic A shows an animal cell in which three elongated strands surrounded by rounded spots are highlighted.

Schematic B shows a cluster of elongated strands labeled as Golgi apparatus, surrounded by rounded spots labeled as membrane enclosed vesicles.

Micrograph C shows an enlarged view of the Golgi apparatus. The Golgi apparatus is surrounded by membrane enclosed vesicles, which are bound to the endoplasmic reticulum that encircles the nuclear envelope. The scale reads 1 micrometer.

Figure 1–24 The Golgi apparatus is composed of a stack of flattened, membrane-enclosed discs. (A) Schematic diagram of an animal cell with the Golgi apparatus colored red. (B) More realistic drawing of the Golgi apparatus. Some of the vesicles seen nearby have pinched off from the Golgi stack; others are destined to fuse with it. Only one stack is shown here, but several can be present in a cell. (C) Electron micrograph that shows the Golgi apparatus in a typical animal cell. (C, courtesy of Brij J. Gupta.)

Schematic A shows a cell with organelles such as lysosome, mitochondrion, peroxisome, Golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, transport vesicle, and nuclear envelope highlighted and labeled.

Schematic B shows a cell, highlighting the region outside the nucleus surrounding the various organelles; this region is labeled cytosol. The cytosol is enclosed within the plasma membrane.

Figure 1–25 Membrane-enclosed organelles are distributed throughout the eukaryotic cell cytoplasm. (A) The various types of membrane-enclosed organelles, shown in different colors, are each specialized to perform a different function. (B) The part of the cytoplasm that fills the space outside of these organelles is called the cytosol (colored blue).

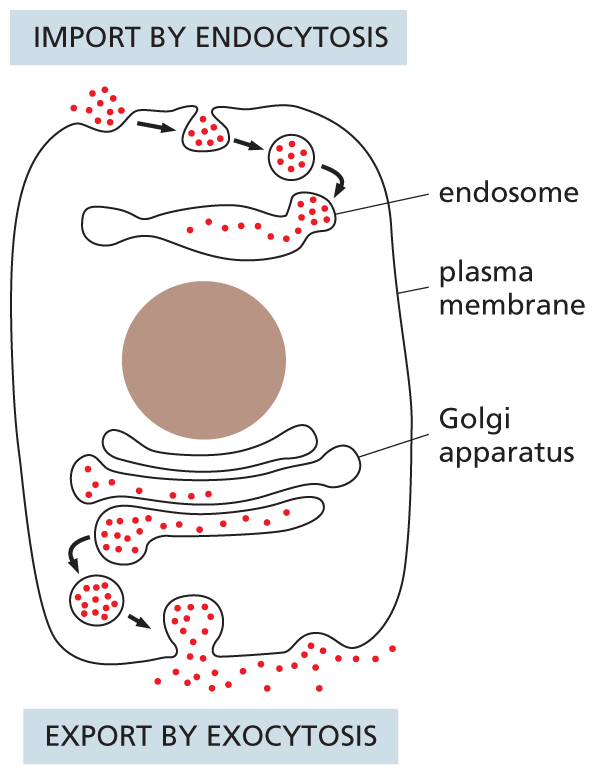

A schematic shows a eukaryotic cell undergoing endocytosis and exocytosis. The top part of the cell shows extracellular materials moving inside the cell through the plasma membrane and then into the endosome. The bottom of the cell shows intracellular materials moving out of the cell from the Golgi apparatus through the plasma membrane.

Figure 1–26 Eukaryotic cells engage in continual endocytosis and exocytosis across their plasma membrane. They import extracellular materials by endocytosis and secrete intracellular materials by exocytosis. Endocytosed material is first delivered to membrane-enclosed organelles called endosomes (discussed in Chapter 15).

A continual exchange of materials takes place between the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi apparatus, the lysosomes, the plasma membrane, and the outside of the cell. The exchange is mediated by transport vesicles that pinch off from the membrane of one organelle and fuse with another, like tiny soap bubbles that bud from and combine with other bubbles. At the surface of the cell, for example, portions of the plasma membrane tuck inward and pinch off to form vesicles that carry material captured from the external medium into the cell—a process called endocytosis (Figure 1–26). Animal cells can engulf very large particles, or even entire foreign cells, by endocytosis. In the reverse process, called exocytosis, vesicles from inside the cell fuse with the plasma membrane and release their contents into the external medium (see Figure 1–26); most of the hormones and signal molecules that allow cells to communicate with one another are secreted from cells by exocytosis. How membrane-enclosed organelles move proteins and other molecules from place to place inside the eukaryotic cell is discussed in detail in Chapter 15.

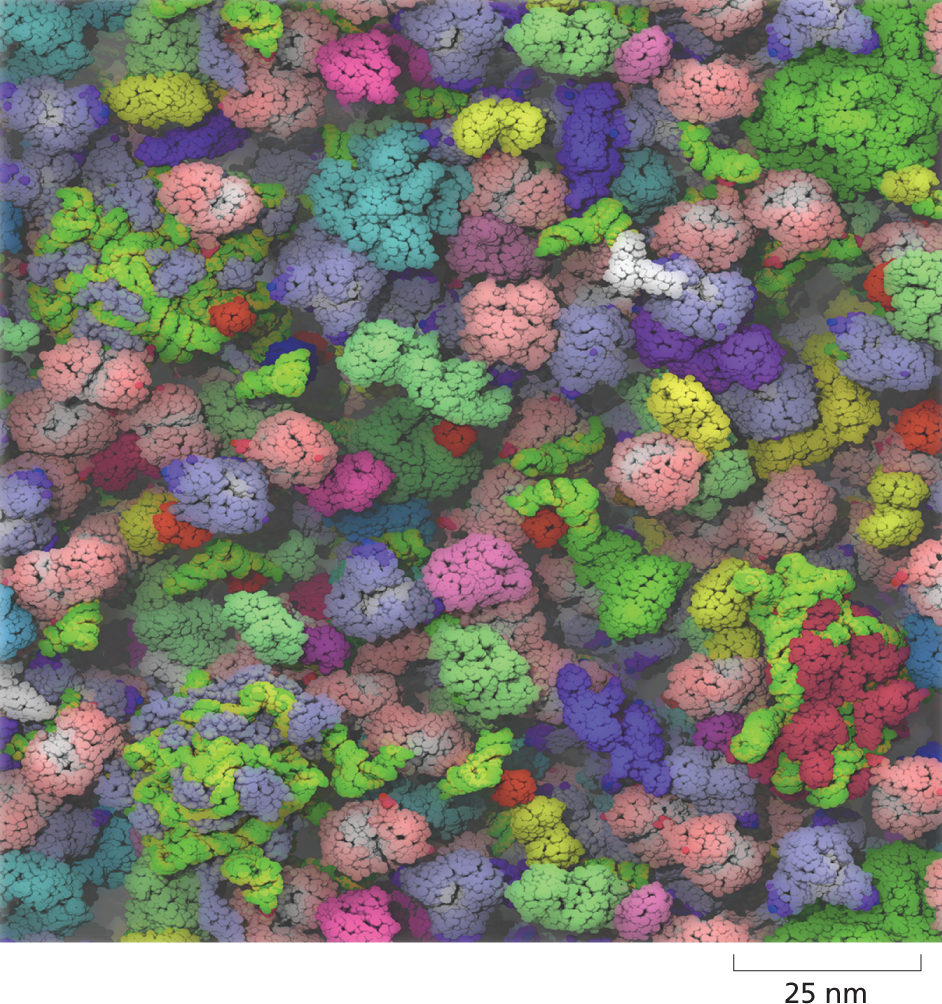

If we were to strip the plasma membrane from a eukaryotic cell and remove all of its membrane-enclosed organelles—including the nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, chloroplasts, and so on—we would be left with the cytosol (Figure 1–25B). In other words, the cytosol is the part of the cytoplasm that is not contained within intracellular membranes. In most cells, the cytosol is the largest single compartment. It contains a host of large and small molecules, crowded together so closely that it behaves more like a water-based gel than a liquid solution (Figure 1–27). The cytosol is the site of many of the chemical reactions that are fundamental to the cell’s existence. The early steps in the breakdown of nutrient molecules take place in the cytosol, for example, and it is here that most proteins are made by ribosomes.

An illustration of the cytosol of Escherichia coli contains tightly packed organelles. The organelles are different shapes, sizes, and colors.

Figure 1–27 The cytosol is extremely crowded. This atomically detailed model of the cytosol of E. coli is based on the sizes and concentrations of 50 of the most abundant large molecules present in the bacterium. RNAs, proteins, and ribosomes are shown in different colors (Movie 1.2). (From S.R. McGuffee and A.H. Elcock, PLoS Comput. Biol. 6:e1000694, 2010.)

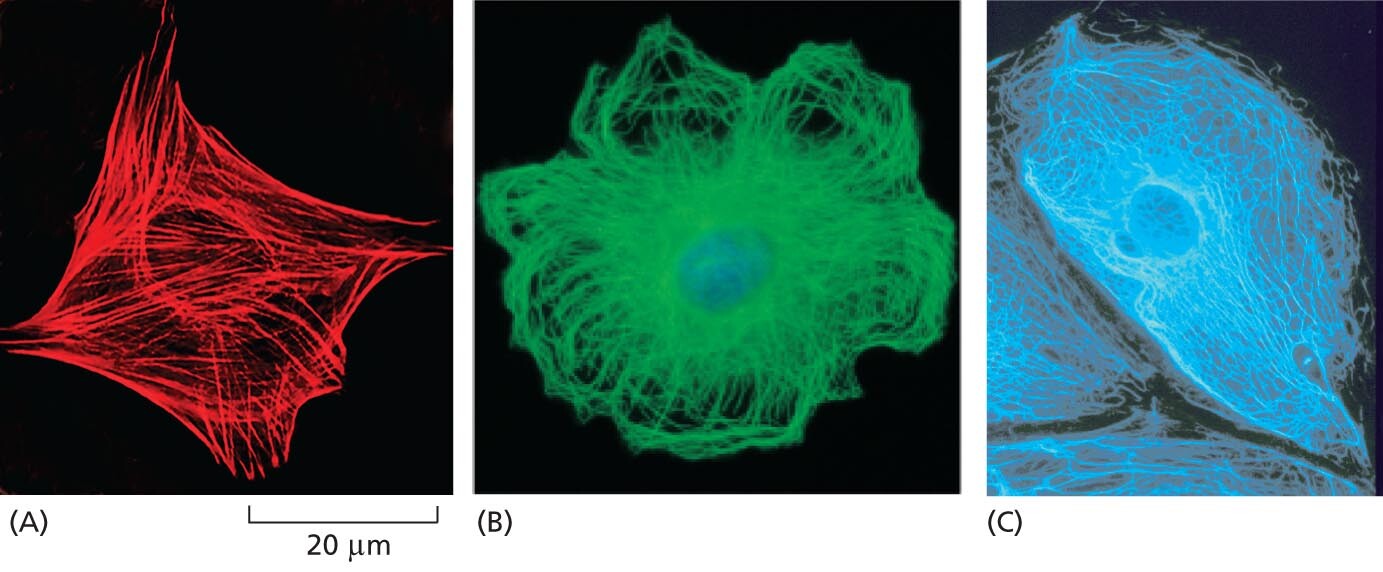

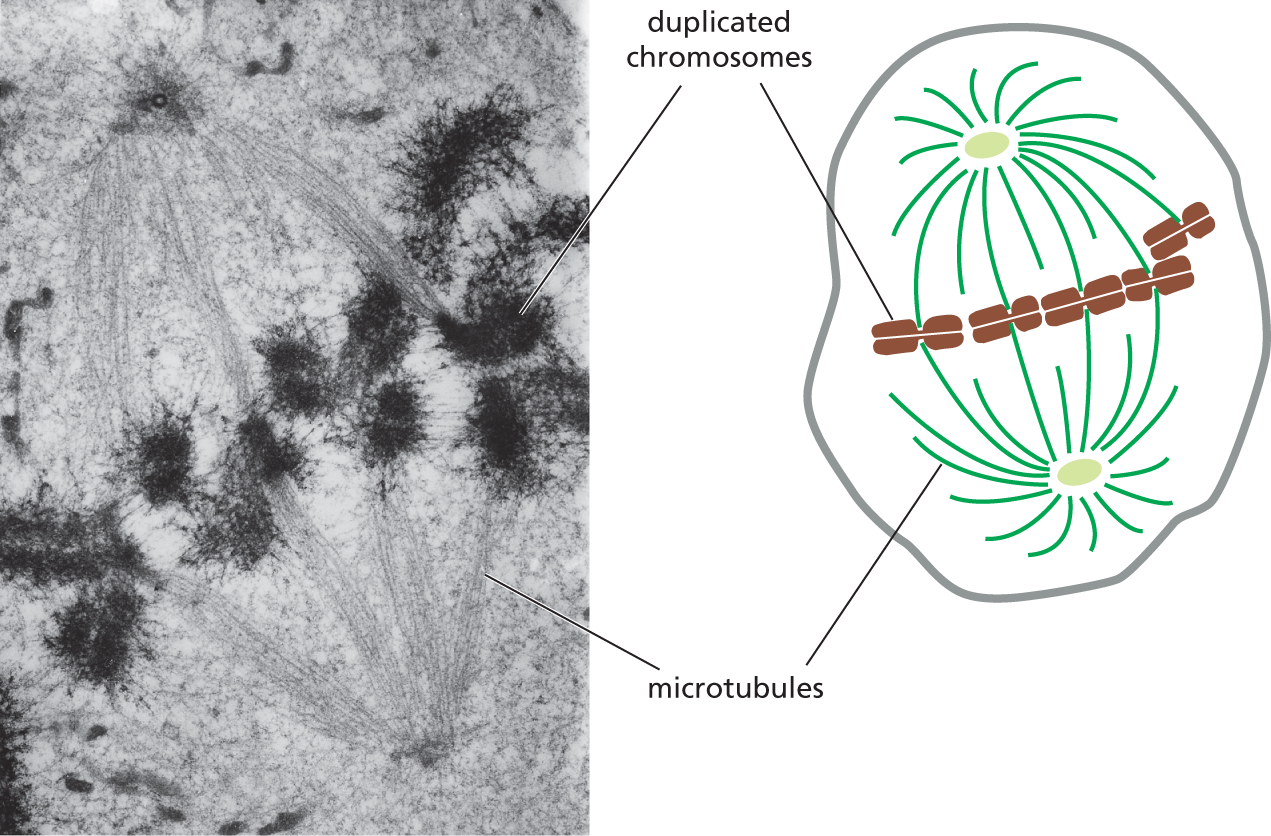

The cytosol is not merely a thin, structureless soup of chemicals and organelles. Using an electron microscope, one can see that in eukaryotic cells the cytosol is crisscrossed by long, fine filaments. Frequently, the filaments are seen to be anchored at one end to the plasma membrane or to radiate out from a central site adjacent to the nucleus. This system of protein filaments, called the cytoskeleton, is composed of three major filament types (Figure 1–28). The thinnest of these filaments are the actin filaments; they are abundant in all eukaryotic cells but occur in especially large numbers inside muscle cells, where they serve as a central part of the machinery responsible for muscle contraction. The thickest filaments in the cytosol are called microtubules (see Figure 1–7B), because they have the form of minute hollow tubes; in dividing cells, they become reorganized into a spectacular array that helps pull the duplicated chromosomes apart and distribute them equally to the two daughter cells (Figure 1–29). Intermediate in thickness between actin filaments and microtubules are the intermediate filaments, which serve to strengthen most animal cells. These three types of filaments, together with other proteins that attach to them, form a system of girders, ropes, and motors that gives the cell its mechanical strength, controls its shape, and drives and guides its movements (Movie 1.3 and Movie 1.4).

A micrograph shows actin filaments as a network of protein filaments that extend from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane. They form a diamond shape that is about 40 micrometers from point to point.

A micrograph shows microtubules as a network of protein filaments that extend from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane. They for a circular, flower like shape.

A micrograph shows intermediate filaments as a network of protein filaments that extend from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane. They fill the whole space of the cell.

Figure 1–28 The cytoskeleton is a network of protein filaments that can be seen crisscrossing the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. The three major types of filaments can be detected using different fluorescent stains. Shown here are (A) actin filaments, (B) microtubules, and (C) intermediate filaments. (A, Molecular Expressions at Florida State University; B, courtesy of Nancy Kedersha; C, courtesy of Clive Lloyd.)

A micrograph A and a schematic B depict a dividing animal cell with duplicated chromosomes attached to the spindle of the microtubules. The micrograph shows darkened patches labeled as duplicated chromosomes on the strands of a mitotic spindle. The schematic shows a rounded cell, within which duplicated chromosomes are aligned horizontally along the center, surrounded by microtubules on either sides. The chromosomes are attached to some of the microtubules.

Figure 1–29 Microtubules help segregate the chromosomes in a dividing animal cell. A transmission electron micrograph and schematic drawing show duplicated chromosomes attached to the microtubules of a mitotic spindle (discussed in Chapter 18). When a cell divides, its nuclear envelope breaks down (see Figure 1–18) and its DNA condenses into visible chromosomes, each of which has duplicated to form a pair of conjoined chromosomes that will ultimately be pulled apart into separate daughter cells by the spindle microtubules. See also Panel 1–1, pp. 12–13. (Photomicrograph courtesy of Conly L. Rieder, Albany, New York.)

QUESTION 1–5

Suggest a reason why it might have been advantageous for eukaryotic cells to have evolved elaborate internal membrane systems that allow them to import substances from the outside, as shown in Figure 1–26.

Because the cytoskeleton governs the internal organization of the cell as well as its external features, it is as necessary to a plant cell—which is boxed in by a tough cell wall—as it is to an animal cell that freely bends, stretches, swims, or crawls. In a plant cell, for example, organelles such as mitochondria are driven in a constant stream around the cell interior along cytoskeletal tracks (Movie 1.5). And animal cells and plant cells alike depend on the cytoskeleton to separate their internal components into two daughter cells during cell division (see Figure 1–29).

The cytoskeleton’s role in cell division may be its most ancient function. Even bacteria contain proteins that are distantly related to those that form the cytoskeletal elements involved in eukaryotic cell division, showing that this class of proteins was present in the very earliest cells; in bacteria, these proteins also form filaments that play a part in cell division. We examine the cytoskeleton in detail in Chapter 17, discuss its role in cell division in Chapter 18, and review how it responds to signals from outside the cell in Chapter 16.

The cell interior is in constant motion. The cytoskeleton is a dynamic jungle of protein ropes that are continually being strung together and taken apart; its filaments can assemble and then disappear in a matter of minutes. Motor proteins use the energy stored in molecules of ATP to trundle along these tracks and cables, carrying organelles and proteins throughout the cytoplasm, and racing across the width of the cell in seconds. In addition, the large and small molecules that fill every free space in the cell are knocked to and fro by random thermal motion, constantly colliding with one another and with other structures in the cell’s crowded cytosol.

Of course, neither the bustling nature of the cell’s interior nor the details of cell structure were appreciated when scientists first peered at cells in a microscope; our knowledge of cell structure accumulated slowly.

A few of the key discoveries are listed in Table 1–1. In addition, Panel 1–2 (p. 27) summarizes the main differences between animal, plant, and bacterial cells.

|

TABLE 1–1 HISTORICAL LANDMARKS IN DETERMINING CELL STRUCTURE |

|

|

1665 |

Hooke uses a primitive microscope to describe small chambers in sections of cork that he calls “cells” |

|

1674 |

van Leeuwenhoek reports his discovery of protozoa. Nine years later, he sees bacteria for the first time |

|

1833 |

Brown publishes his microscopic observations of orchids, clearly describing the cell nucleus |

|

1839 |

Schleiden and Schwann propose the cell theory, stating that the nucleated cell is the universal building block of plant and animal tissues |

|

1857 |

von Kölliker describes mitochondria in muscle cells |

|

1879 |

Flemming describes with great clarity chromosome behavior during mitosis in animal cells |

|

1881 |

Ramón y Cajal and other histologists develop staining methods that reveal the structure of nerve cells and the organization of neural tissue |

|

1898 |

Golgi first sees and describes the Golgi apparatus by staining cells with silver nitrate |

|

1902 |

Boveri links chromosomes and heredity by observing chromosome behavior during sexual reproduction |

|

1952 |

Palade, Porter, and Sjöstrand develop methods of electron microscopy that enable many intracellular structures to be seen for the first time. In one of the first applications of these techniques, Huxley shows that muscle contains arrays of protein filaments—the first evidence of a cytoskeleton |

|

1957 |

Robertson describes the bilayer structure of the cell membrane, seen for the first time in the electron microscope |

|

1960 |

Kendrew describes the first detailed protein structure (sperm whale myoglobin) to a resolution of 0.2 nm, using x-ray crystallography. Perutz proposes a lower-resolution structure for hemoglobin |

|

1965 |

de Duve and colleagues use a cell-fractionation technique to separate peroxisomes, mitochondria, and lysosomes from a preparation of rat liver |

|

1968 |

Petráňn and collaborators make the first confocal microscope |

|

1970 |

Frye and Edidin use fluorescent antibodies to show that plasma membrane molecules can diffuse in the plane of the membrane, indicating that cell membranes are fluid |

|

1974 |

Lazarides and Weber use fluorescent antibodies to stain the cytoskeleton |

|

1994 |

Chalfie and collaborators introduce green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a marker to follow the behavior of proteins in living cells |

|

1990s–2000s |

Betzig, Hell, and Moerner develop techniques for superresolution fluorescence microscopy that allow observation of biological molecules too small to be resolved by conventional light or fluorescence microscopy |

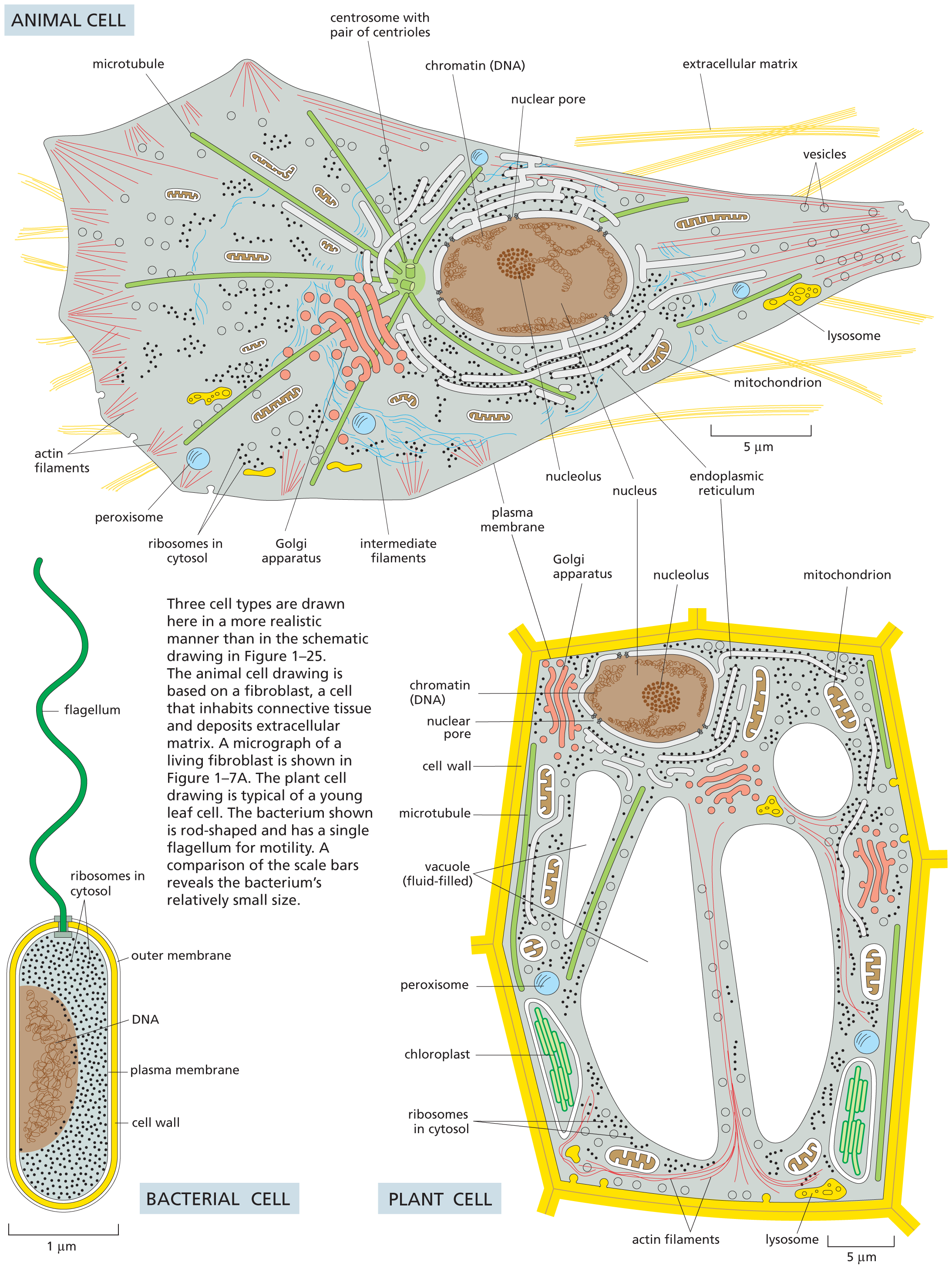

PANEL 1–2 CELL ARCHITECTURE

A 3 panel illustration shows an animal cell, a bacterial cell, and a plant cell. The parts labeled inside the animal cell are as follows: microtubule, centrosome with pair of centrioles, chromatin (D N A), nuclear pore, extracellular matrix, vesicles, lysosome, mitochondrion, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, nucleolus, plasma membrane, intermediate filaments, Golgi apparatus, ribosomes in cytosol, peroxisome, and actin filaments. The parts labeled in bacterial cell are as follows: outer membrane, cell wall, plasma membrane, ribosomes in cytosol, D N A, and flagellum. The parts labeled in plant cell are as follows: mitochondrion, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleolus, nucleus, Golgi apparatus, plasma membrane, chromatin (D N A), nuclear pore, cell wall, microtubule, vacuole (fluid filled), peroxisome, chloroplast, ribosomes in cytosol, actin filaments, and lysosome.

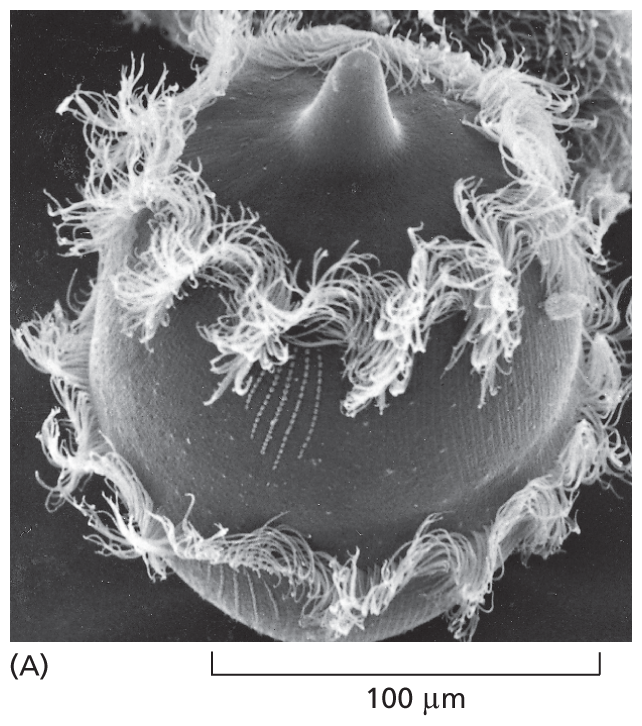

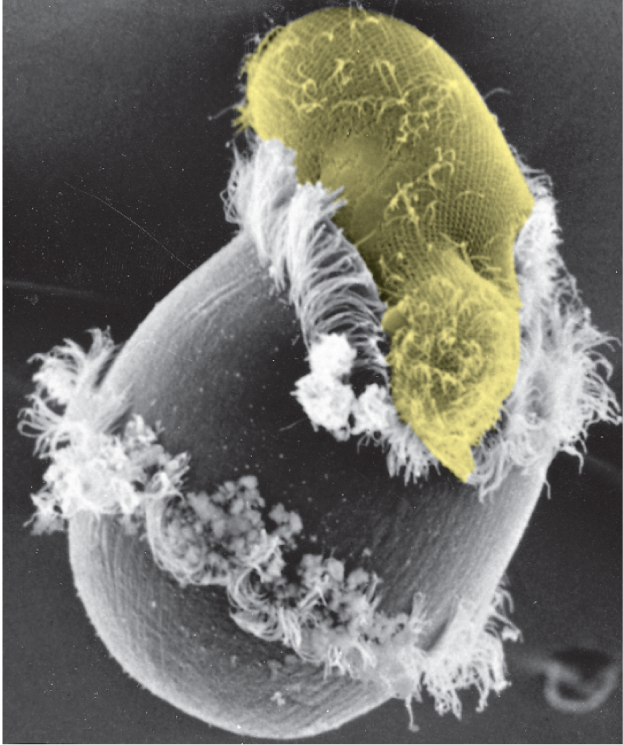

Although all multicellular organisms are eukaryotes, many eukaryotic species lead a more solitary life. Such free-living, motile, unicellular eukaryotes are called protozoans. These cells may not inhabit the range of extreme environments that are colonized by bacteria and archaea, but they do adopt an impressive variety of behaviors and appearances. Didinium, for example, is a large, carnivorous protozoan with a diameter of about 150 μm—roughly 10 times that of the average human cell. It has a globular body encircled by two fringes of cilia, and its front end is flattened except for a single protrusion rather like a snout (Figure 1–30A). Didinium uses its beating cilia to swim at high speed, and when the organism encounters a suitable prey, usually another type of protozoan, it releases numerous small, paralyzing darts from its snout region. Didinium then attaches to and devours the other cell, inverting like a hollow ball to engulf its victim, which can be almost as large as the protozoan itself (Figure 1–30B).

Micrograph A shows a Didinium. It is a rounded cell with a snout on top and two rings of cilia along its circumference. It is about 125 micrometers wide.

Micrograph B shows an oval shaped ciliated protozoan being ingested into the top part of a Didinium. The Didinium is starting to wrap around the protozoan.

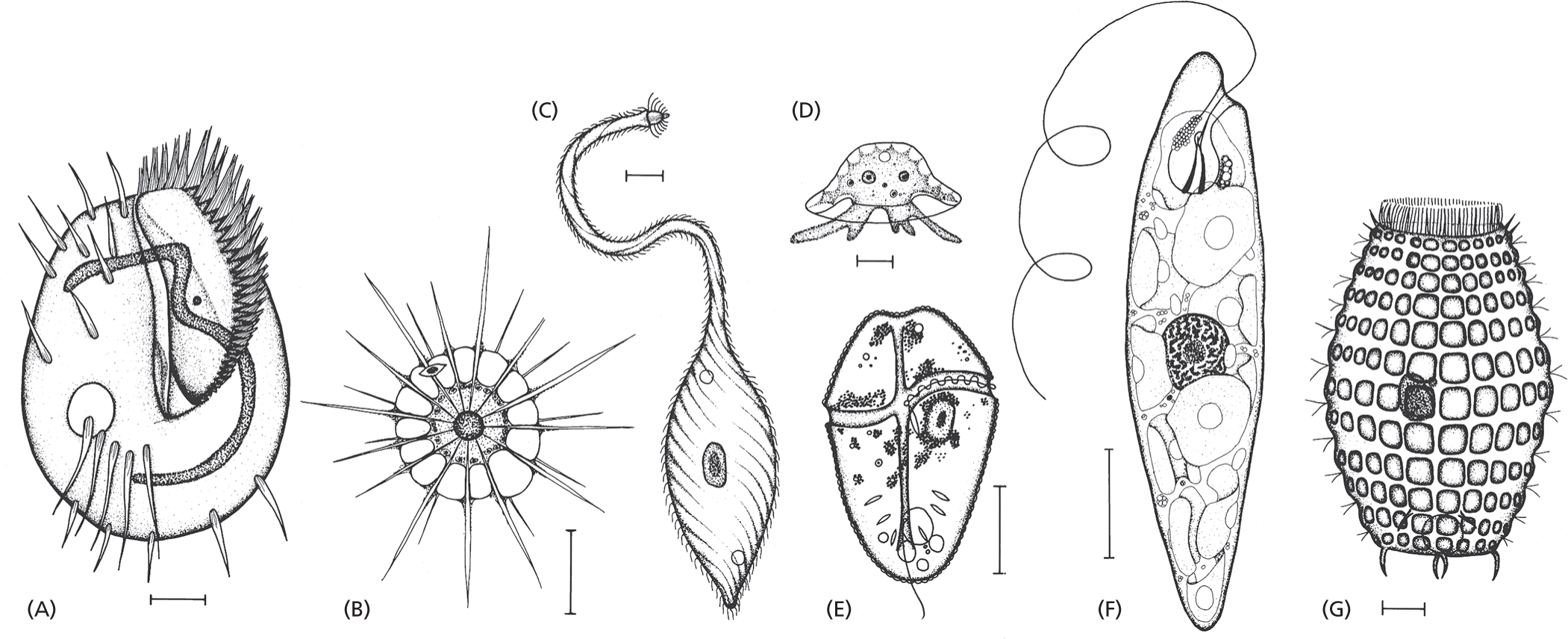

Not all protozoans are predators. They can be photosynthetic or carnivorous, motile or sedentary. Their anatomy is often elaborate, occasionally ostentatious, and it includes such structures as sensory bristles, photoreceptors, sinuously beating cilia, stalklike appendages, mouthparts, stinging darts, and musclelike contractile bundles. Although they are single cells, protozoans can be as intricate and versatile as many multicellular organisms (Figure 1–31). Much can be learned about fundamental cell biology from studies of these fascinating life-forms, including the origins of multicellularity and the mysteries of our own evolutionary past.

Seven schematics of diverse protozoans labeled from A through G. Schematics A, C, and G show protozoans with cilia on their body surface; B shows a protozoan with spiked projections extending outward from its spherical body; D shows an amoeba with finger like projections; and E and F show protozoans with flagella.

Figure 1–31 An assortment of protozoans illustrates the enormous variety within this class of single-celled eukaryotes. These drawings are done to different scales, but in each case the scale bar represents 10 μm. The organisms in (A), (C), and (G) are ciliates; (B) is a heliozoan; (D) is an amoeba; (E) is a dinoflagellate; and (F) is a euglenoid. To see the latter in action, watch Movie 1.6. Because these organisms can be seen only with the aid of a microscope, they—like bacteria and archaea—are also referred to as microorganisms. (From M.A. Sleigh, The Biology of Protozoa. London: Edward Arnold, 1973. With permission from Edward Arnold.)