Pause to Consider

- How do you define or describe rigor?

- How does your version compare to the one provided in this unit, and what might account for the differences?

Before delving into the research on rigor, it seems important to elaborate on what we mean by rigor, and to expand on some of the ways the term rigor is used and misused. Common descriptions of rigor associate it with volume (like the number of assignments or hours spent studying) or curricular level (as in, calculus is more rigorous than algebra). Some think of rigor as thoroughness or accuracy, while others imagine severity or strictness, as in demanding, difficult, or extreme conditions. As Jack and Sathy write, “Far too many faculty members still think a challenging course should be like an obstacle race”—one in which “you, as the instructor, set up the tasks and each student has to finish them (or not) to a certain standard and within a set time. If only a few students can do it, that means the course is rigorous.”20 Professor emeritus of biology Craig Nelson famously reflects on ideas he dubs “dysfunctional illusions of rigor” that had informed his teaching practices, describing his personal realization that many so-called rigorous practices disadvantage students.21

We define rigor as academic challenge that supports student learning and growth, and we contend that it is essential to equity-minded teaching for the three reasons noted previously: to highlight rigor’s relationship to learning, to counter the deficit-based belief that inclusion means lowered standards, and to affirm that students have boundless potential best tapped by high standards and support. After isolating a few key insights from the research on how rigor facilitates learning, we will summarize perspectives on the relationship between rigor and equity.

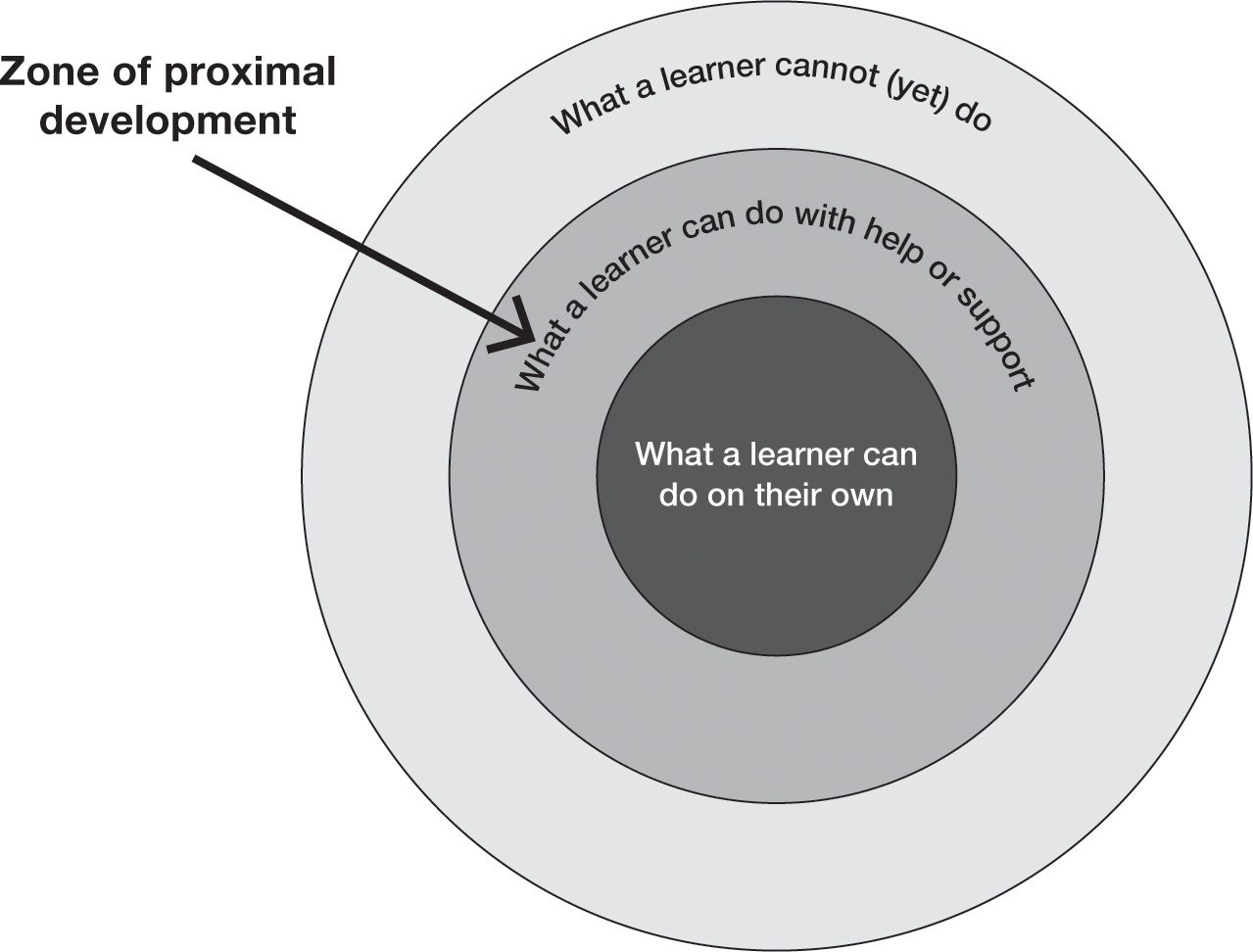

How does being challenged support learning? One well-established connection was developed by Russian and Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky in the 1930s. Vygotsky described the optimal level of challenge—the “sweet spot” for learning—as a theoretical space existing between what an individual can learn independently and what they can learn with guidance or in partnership with others. This sweet spot is known as the zone of proximal development; see figure 1.1. For us as educators, one of the key takeaways from this connection is that to maximize learning, we must appropriately challenge students. If we aim too low, students won’t devote sufficient effort or time to the learning task, and if we aim too high or offer insufficient support, students may think the task is impossible and disengage. Identifying the appropriate level of challenge can be difficult and usually takes time to calibrate (but don’t despair: low- or no-stakes assessments can help, especially early in the semester). Vygotsky’s theory also counters the perspective that providing students with support represents a reduction in rigor.22 Even the toughest critics of active learning and group work might be excited to find out that they can pose more cognitively demanding challenges to students if they provide adequate support.

A diagram shows three concentric circles. The outer circle has the label “What a learner cannot (yet) do,” the next circle has the label “What a learner can do with help or support,” and the innermost circle has the label “What a learner can do on their own.” An arrow leading to the second circle has the label “Zone of proximal development.”

According to psychologist Lev Vygotsky, the “zone of proximal development” describes the space between what a learner can already do and what they can’t yet do. Finding the “sweet spot” in the middle involves balancing rigor with support.

At the same time, equity-minded faculty pair rigor with support. We must not overlook the importance of enabling students to achieve success when facing academic challenges with the guidance of or in partnership with others. Students’ ability to succeed with support is a primary reason why meaningful, well-structured collaborative learning experiences can be so effective. Intentionally designed and facilitated discussion forums can serve this purpose in both online and in-person courses, but they’re especially helpful in fully online classes, where other forms of collaboration (like group projects) tend to pose challenges for students with shifting work schedules or busy home lives. We’ll share specific examples and recommendations in Unit 2 on transparency and in Section Two when we consider what equity-focused online teaching looks like on a day-to-day basis.

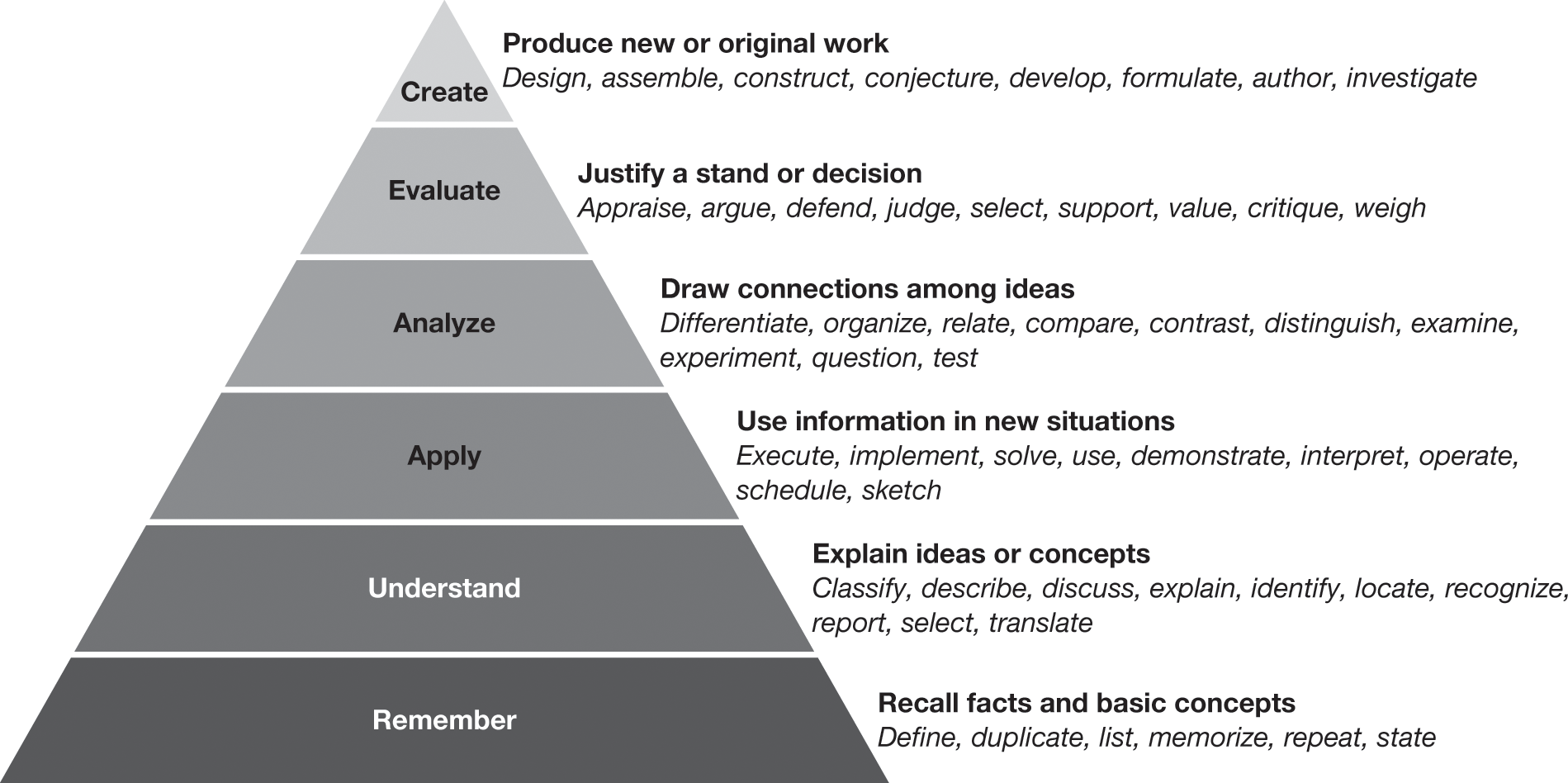

Bloom’s taxonomy (see figure 1.2) also helps make the connection between learning and rigor. It describes six levels of cognitive demand—from the recalling of facts to analysis, evaluation, and creation. When Benjamin Bloom and fellow educational psychologists studied the questions commonly posed to students in college settings, they found that more than 95 percent of test questions required students only to recall information. The resulting taxonomy (first published in 1956 and updated in 2001) has since been used by educators at all levels in the design of curriculum and assessments that include varied levels of cognitive challenge.

A diagram shows a list of words organized into a pyramid. At the top of the pyramid is the word “Create,” with the description “Produce new or original work: design, assemble, construct, conjecture, develop, formulate, author, investigate.” The next word in the pyramid is “Evaluate,” with the description: “Justify a stand or decision: appraise, argue, defend, judge, select, support, value, critique, weigh.” The next word in the pyramid is “Analyze,” with the description “Draw connections among ideas: Differentiate, organize, relate, compare, contrast, distinguish, examine, experiment, question, test.” The next word in the pyramid is “Apply,” with the description “Use information in new situations: Execute, implement, solve, use, demonstrate, interpret, operate, schedule, sketch.” The next word in the pyramid is “Understand,” with the description “Explain ideas or concepts: Classify, describe, discuss, explain, identify, locate, recognize, report, select, translate.” The final word in the pyramid is “Remember,” with the description: “Recall facts and basic concepts: Define, duplicate, list, memorize, repeat, state.”

This widely used learning framework, developed in 1956 and later refined, envisions learning activities along a continuum from basic fact recall to complex thinking and ideation.

Source: Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

As we’ve alluded to previously, rigor is a complex and contentious topic. In relation to equity, the research suggests that rigor is both a critical problem and a key solution. Perhaps the most critical problem is that many teachers and faculty, often without being aware of it, continue to have lower academic expectations for their students of color. Implicit in this practice is the sense that some students are capable of rigorous work while others are not—and importantly, that an individual faculty member can immediately tell the difference. Given how little we know about our students and their actual abilities and lived experiences when they enroll in our courses, it seems we might be conflating students’ capabilities with what we can observe, whether their background knowledge or our assumptions based on their identities.

In terms of race, psychologist and multiculturalism expert Derald Wing Sue and his colleagues refer to the latter as the “ascription of intelligence”—the act of “assigning intelligence to a person of color on the basis of their race,” a common racial microaggression.23 They explain that microaggressions are “brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to people of color because they belong to a racial minority group.”24 Racial microaggressions, specifically, are “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color.” As equity-minded faculty, we recognize that students will enter our classrooms with varied levels of academic preparation and knowledge of our specific disciplines. Yet we also engage in self-examination, get to know our students, and resist making assumptions about their capabilities. Instead, we believe in and demonstrate our belief in students’ potential, set the bar high, and increase support structures.

Although the impact of teacher expectations on student learning and performance has been famously difficult to study, many scholars have drawn a direct line between the two. As Kingsborough Community College professor of English Emily Schnee states plainly, “Low teacher expectations of Black students are well-documented and theorized to be a significant contributing factor in suppressing Black students’ academic achievement.”25 Similarly, Zaretta Hammond, a leading scholar of culturally responsive teaching, correlates rigor and so-called “achievement gaps.” She cites classroom studies that document the fact that underserved English learners, low-income students, and students of color routinely receive less instruction in higher-order skills development than other students do. As a result, Hammond argues, many of these students are dependent learners who are not yet ready for the academic challenges they encounter in college.26 Most recently, a comprehensive study conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research found a strong correlation between teacher expectations and college completion as well as evidence of racial bias in teachers’ expectations, affirming that “white teachers, who comprise the vast majority of American educators, have far lower expectations for Black students than they do for similarly situated white students.”27

Daniel Solorzano, Miguel Ceja, and Tara Yosso provided a vivid illustration of this damaging phenomenon via one student’s retelling of an experience with a faculty member:

I was doing really well in the class, like math is one of my strong suits. . . . We took a first quiz . . . and I got like a 95. . . . He [the professor] was like, “Come into my office. We need to talk,” and I was like, “Okay.” I just really knew I was gonna be [told] “great job,” but he [said], “We think you’ve cheated. . . . We just don’t know, so we think we’re gonna make you [take the exam] again.” . . . And [then] I took it with just the GSI [graduate student instructor] in the room, and just myself, and I got a 98 on the exam.28

Despite acknowledging the prevalence and impact of experiences like this one, leading scholars and practitioners of equity-minded teaching—past and present—insist that we cannot attain equitable outcomes without rigor. In the Jim Crow era, Black educators, as well as those who sought to stop them from teaching Black students and/or to limit these students to technical or applied content, understood the power of education and of critical thought.29 Civil rights leader and educator Bob Moses uses the term “sharecropper education” to describe the limited, preassigned roles for which Black individuals were allowed to be prepared.30

A rigorous education counters the historical legacy of these societal forces and their contemporary manifestations. bell hooks recalls that she was taught that a “devotion to learning, to a life of the mind” was a form of resistance. Moses took a rigorous, discipline-based approach to empowering students to succeed in a postindustrial society. In 1982, he found out his eighth-grade daughter, Maisha, would not learn algebra because it was not offered at her school.31 He knew that without this foundation she would be ineligible for honors math and science classes in high school—which would limit (or at least delay) her STEM literacy and career prospects. Believing firmly that math proficiency is a gateway to equality, Moses in 1982 founded the Algebra Project, a nonprofit dedicated to teaching algebra in culturally relevant ways to students who were often tracked into less rigorous classes. As of 2021, the Algebra Project had helped more than 40,000 students in hundreds of schools nationwide,32 with results ranging from higher scores on district and state-level exams to confidence in math ability and placement into higher levels of math courses.33

The combination of rigor paired with support exemplified by the Algebra Project features prominently in Hammond’s model of culturally responsive teaching. “While the achievement gap has created the epidemic of dependent learners,” she writes, “culturally responsive teaching is one of our most powerful tools for helping students find their way out of the gap.”34 In fact, Hammond includes a “Ready for Rigor” framework within her book and her approach. Similarly, Luke Wood, in his text Black Minds Matter, focuses on the education of Black males and urges us to establish and convey high expectations “to counter pervasive messages that Black learners receive from educators, peers, family, and society at large that communicate their inability to succeed academically.”35 He also reminds us that students need to know we believe in them and that rigor needs to be balanced with support. Through an inclusive approach to rigor, we empower students and create the conditions in which they can strengthen their cognitive skills, surpass all expectations regarding their ability, and reap the liberatory benefits of learning.

These summaries of contemporary theories of motivation and culturally relevant (or responsive) teaching and of the literature on rigor only skim the surface of vast bodies of research. Yet they underscore the centrality of relevance and rigor to student learning and success, particularly for students with minoritized identities. An important caveat is that the implementation of these tools must be approached with authenticity and depth. When motivation is reduced to students’ interests, versus their values or goals, or when culturally relevant teaching is reduced to superficial, symbolic tasks such as eating ethnic or cultural foods or listening to ethnic or cultural music, it will not reap its intended benefits. Rigor, in turn, must reflect actual cognitive challenge and be coupled with both our support and our belief in students’ capacity for success. The section that follows homes in on a potent yet often untapped opportunity to increase learning equity via the power of relevance and rigor: course design, drawing on the key research principles on relevance we have just distilled.