How Do Anthropologists Get Started Conducting Fieldwork?

Summarize the key fieldwork research strategies, skills, and perspectives.

Today, cultural anthropologists call on a set of techniques designed to assess the complexity of human interactions and social organizations. You probably use some variation of these techniques as you go about daily life and make decisions for yourself and others. For a moment, imagine yourself doing fieldwork with Nancy Scheper-Hughes in the Brazilian shantytown of Alto do Cruzeiro. How would you prepare yourself? What strategies would you use? How would you analyze your data? What equipment would you need to conduct your research?

PREPARATION

Prior to beginning fieldwork, anthropologists go through an intense process of preparation, carefully assembling an anthropologist’s toolkit: all the information, perspectives, strategies, and even equipment that may be needed. We start by reading everything we can find about our research site and the particular issues we will be examining. This literature review provides a crucial background for the experiences to come. Following Malinowski’s recommendation, anthropologists also learn the language of their field site. The ability to speak the local language eliminates the need to work through interpreters and allows us to participate in the community’s everyday activities and conversations, which richly reflect local culture.

Before going to the field, anthropologists search out possible contacts: other scholars who have worked in the community, community leaders, government officials, perhaps even a host family. A specific research question or problem is defined and a research design created. Grant applications are submitted to seek financial support for the research. Permission to conduct the study is sought ahead of time from the local community and, where necessary, from appropriate government agencies. Protocols are developed to protect those who will be the focus of the research. Anthropologists attend to many of these logistical matters following a preliminary visit to the intended field site before fully engaging in the fieldwork process.

Finally, we assemble all the equipment needed to conduct our research. Today this aspect of your anthropologist’s toolkit—most likely a backpack—might include a notebook, pens, camera, voice recorder, maps, cell phone, batteries and chargers, dictionary, watch, and identification.

STRATEGIES

Once in the field, anthropologists apply a variety of research strategies for gathering quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative data include statistical information about a community—data that can be measured and compared, including details of population demographics and economic activity. Qualitative data include information that cannot be counted but may be even more significant for understanding the dynamics of a community. Qualitative data consist of personal stories and interviews, life histories, and general observations about daily life drawn from participant observation. Qualitative data enable the ethnographer to connect the dots and answer the questions of why people behave in certain ways or organize their lives in particular patterns.

Central to a cultural anthropologist’s research is participant observation. By participating in our subjects’ daily activities, we experience their lives from the perspective of an insider. Through participant observation over time, we establish rapport—relationships of trust and familiarity with members of the community we study. The deepening of that rapport through intense engagement enables the anthropologist to move from being an outsider toward being an insider. Over time in a community, anthropologists seek out people who will be our advisors, teachers, and guides—sometimes called key informants or cultural consultants. Key informants may suggest issues to explore, introduce community members to interview, provide feedback on research insights, and warn against cultural miscues. (Again, quoting from Scheper-Hughes: “Ze Antonio advised me to ignore Nailza’s odd behavior, which he understood as a kind of madness that, like the birth and death of children, came and went.”)

Another key research method is the interview. Anthropologists are constantly conducting interviews while in the field. Some interviews are very informal, essentially gathering data through everyday conversation. Other interviews are highly structured, closely following a set of questions. Semi-structured interviews use those questions as a framework but leave room for the interviewee to guide the conversation. One particular form of interview, a life history, traces the biography of a person over time, examining changes in the person’s life and illuminating the interlocking network of relationships in the community. Life histories provide insight into the frameworks of meaning that individuals build around their life experiences. Surveys can also be developed and administered to gather quantitative data on key issues and to reach a broader sample of participants but rarely do they supersede participant observation and face-to-face interviews as the anthropologist’s primary strategy for data collection.

Anthropologists also map human relations. Kinship analysis enables us to explore the interlocking relationships of power built on family and marriage (see Chapter 9). In more urban areas where family networks are diffuse, a social network analysis may prove illuminating. One of the simplest ways to analyze a social network is to identify whom people turn to in times of need.

Central to our data-gathering strategy, anthropologists write detailed field notes of our observations and reflections. These field notes take various forms. Some are elaborate descriptions of people, places, events, sounds, and smells. Others are reflections on patterns and themes that emerge, questions to be asked, and issues to be pursued. Some field notes are personal reflections on the experience of doing fieldwork—how it feels physically and emotionally to be engaged in the process. Although the rigorous recording of field notes may sometimes seem tedious, the collection of data over time allows the anthropologist to revisit details of earlier experiences, to compare information and impressions over time, and to analyze changes, trends, patterns, and themes.

Sophisticated computer programs can assist in the organization and categorization of data about people, places, and institutions. But in the final analysis, the instincts and insights of the ethnographer are key to recognizing significant themes and patterns.

MAPPING

Often, one of the first steps an anthropologist takes upon entering a new community is to map the surroundings. Mapping takes many forms and produces many different products. While walking the streets of the field site, the ethnographer develops a spatial awareness of where people live, work, worship, play, and eat and of the space through which they move. After all, human culture exists in real physical space. And culture shapes how space is constructed and used. Likewise, physical surroundings influence human culture, shaping the boundaries of behavior and imagination. Careful observation and description, recorded in maps, field notes, audio and video recordings, and photographs, provide the material for deeper analysis of these community dynamics.

Urban ethnographers describe the power of the built environment to shape human life. Most humans live in a built environment, not one made up solely or primarily of nature. By focusing on the built environment—what we have built around us—scholars can analyze the intentional development of human settlements, neighborhoods, towns, and cities. Growth of the built environment is rarely random. Rather, it is guided by political and economic choices that determine funding for roads, public transportation, parks, schools, lighting, sewers, water systems, electrical grids, hospitals, police and fire stations, and other public services and infrastructure. Local governments establish and enforce tax and zoning regulations to control the construction of buildings and approved uses. Mapping the components of this built environment may shed light on key dynamics of power and influence in a community.

More information

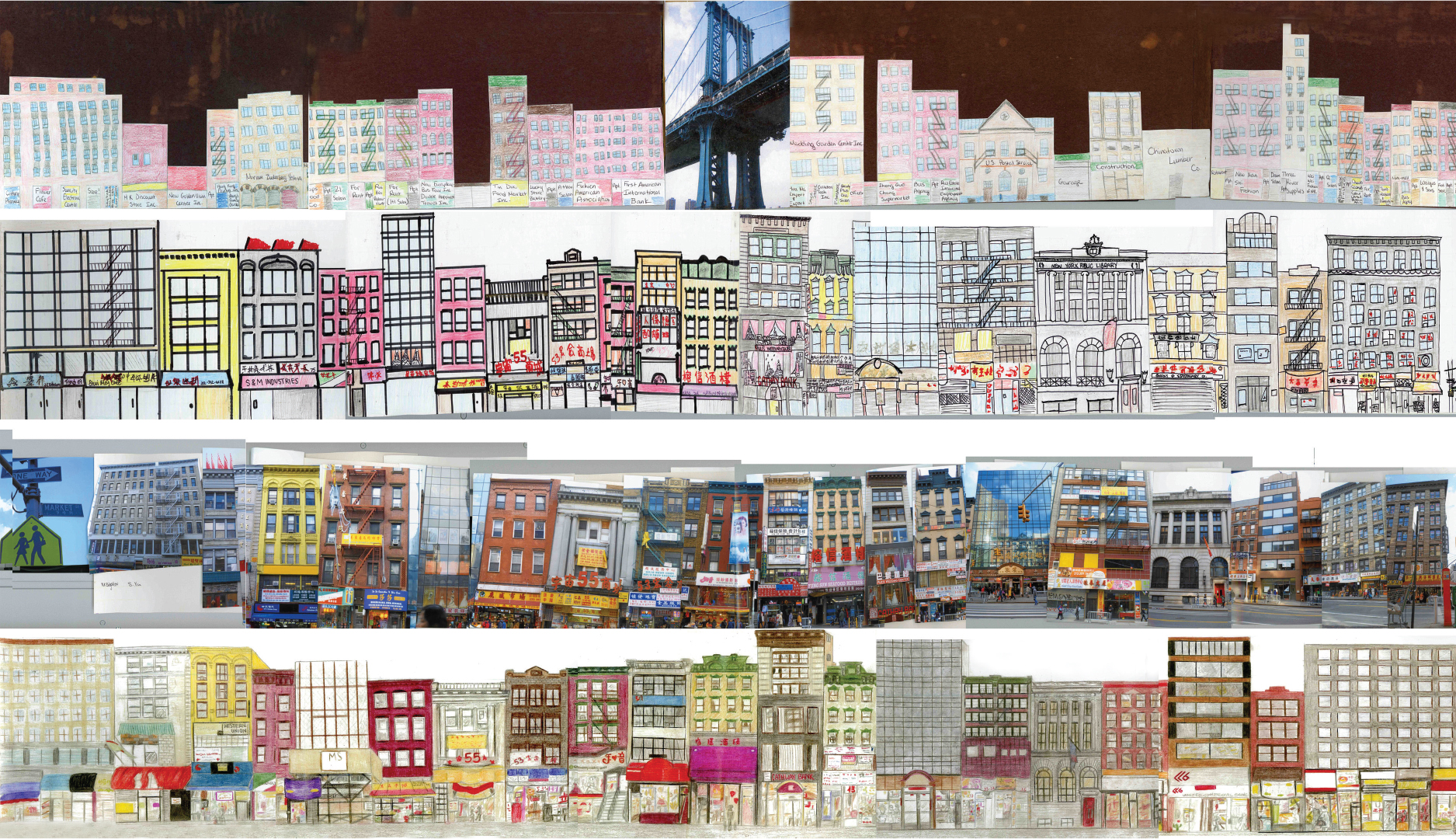

Four rows of artwork of building facades of a New York City street. In the top row, the buildings are colored with crayon, labeled in English, and cut out, and there’s a photo of the Manhattan Bridge in the middle. In the second row, the buildings are colored with pencil and most of them are labeled with Chinese characters. The third row includes photos of each individual building placed next to each other. The bottom row is colored with details of the contents of the ground floors of the businesses.

Anthropologists turn to quantitative data to map who is present in a community, including characteristics such as age, gender, family type, and employment status. This demographic data may be available through the local or national census, or, if the sample size is manageable, the anthropologist may choose to gather the data directly by surveying the community. To map historical change over time in an area and to discern its causes, anthropologists also turn to archives, newspaper databases, minutes and records of local organizations, historical photos, and personal descriptions, in addition to census data.

Mapping today may be aided by online tools such as satellite imagery, geographic information system devices and data, online archives, and electronic databases. All can be extremely helpful in establishing location, orientation, and, in the case of photo archives, changes over time. On their own, however, these tools do not provide the deep immersion sought by anthropologists conducting fieldwork. Instead, anthropologists place primary emphasis on careful, firsthand observation and documentation of physical space as a valuable strategy for understanding the day-to-day dynamics of cultural life.

SKILLS AND PERSPECTIVES

Successful fieldwork requires a unique set of skills and perspectives that are hard to teach in the classroom. Ethnographers must begin with open-mindedness about the people and places they study. We must be wary of any prejudices we might have formed before our arrival, and we must be reluctant to judge once we are in the field. Boas’s notion of cultural relativism is an essential place to begin: Can we see the world through the eyes of the people we are studying? Can we understand their systems of meaning and internal logic? The tradition of anthropology suggests that cultural relativism must be the starting point if we are to accurately hear and retell the stories of others.

A successful ethnographer must also be a skilled listener. We spend a lot of time in conversation, but much of that time involves listening, not talking. The ability to ask good questions and to listen carefully to the responses is essential. A skilled listener hears both what is said and what is not said. Zeros are the elements of a story or a picture that are not told or seen—key details omitted from the conversation or key people absent from the room. Zeros offer insights into issues and topics that may be too sensitive to discuss or display publicly.

A good ethnographer must be patient, flexible, and open to the unexpected. Sometimes sitting still in one place is the best research strategy because it offers opportunities to observe and experience unplanned events and unexpected people. The overscheduled fieldworker can easily miss the mundane imponderabilia that constitute the richness of everyday life. For instance, I have a favorite tea shop in one Chinese village where I like to sit and wait to see what happens.

At times, the most important, illuminating conversations and interviews are not planned ahead of time. Patience and a commitment to conducting research over an extended period allow the ethnographic experience to come to us on its own terms, not on the schedule we assign to it. This is one of the significant differences between anthropology and journalism. It is also a hard lesson to learn and a hard skill to develop.

More information

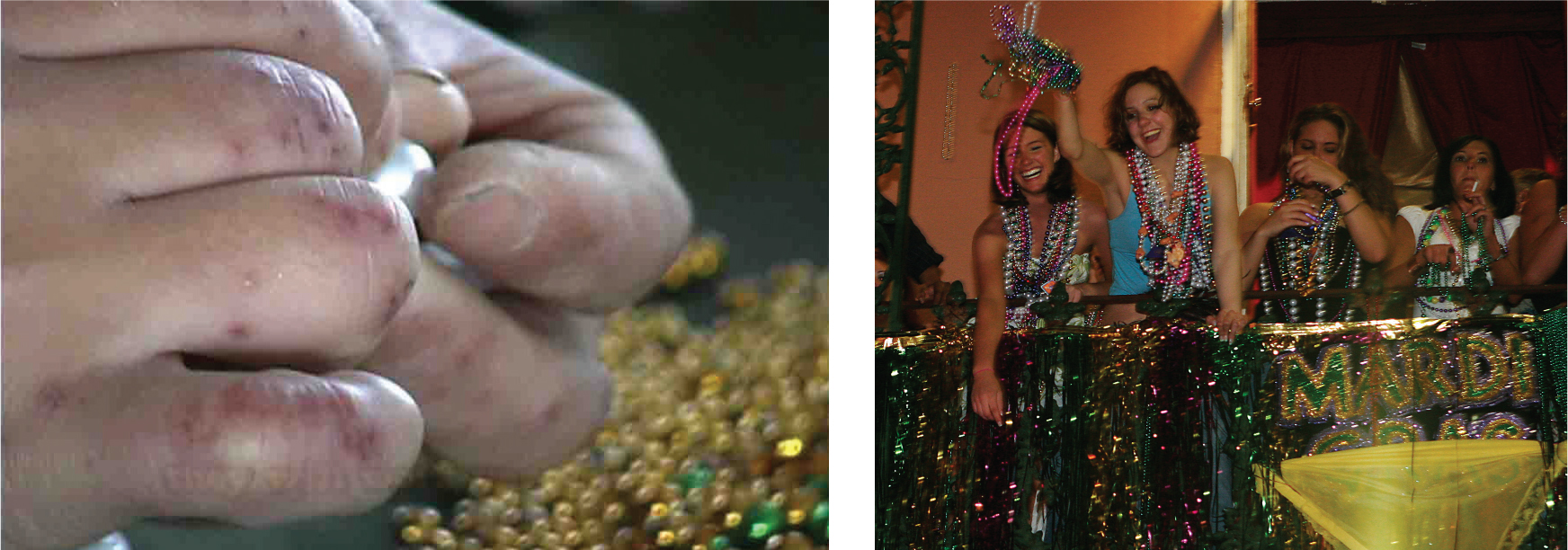

Blistered hands hold a bead. Yellow and green beans shine in the background.

Young women wearing colorful bead necklaces stand on a balcony. One is catching beads in the air. A sign on the balcony reads Mardi Gras.

A final perspective essential for a successful ethnographer is openness to the possibility of mutual transformation in the fieldwork process. This is risky business because it exposes the personal component of anthropological research. It is clear that by participating in fieldwork, anthropologists alter—in ways large and small—the character of the community being studied. But if you ask them about their fieldwork experience, they will acknowledge that in the process they themselves become transformed on a very personal level—their self-understanding, their empathy for others, their worldviews. The practice of participant observation over time entails building deep relationships with people from another culture and directly engages the ethnographer in the life of the community.

Nancy Scheper-Hughes could not have returned unchanged by her research experience. The people of Alto do Cruzeiro would not let her simply observe their lives; they made her work with them to organize a neighborhood organization to address community problems. Indeed, the potential for the fieldworker to affect the local community is very great. So is the potential for the people being studied to transform the fieldworker.

ANALYSIS

As the fieldwork experience proceeds, anthropologists regularly reflect on and analyze the trends, issues, themes, and patterns that emerge from their carefully collected data. One framework for analysis that we will examine in this book is power: Who has it? How do they get it and keep it? Who uses it, and why? Where is the money, and who controls it? The anthropologist Eric Wolf thought of culture as a mechanism for facilitating relationships of power—among families, genders, religions, classes, and political entities (1999). Good ethnographers constantly assess the relations of power in the communities they study.

Ethnographers also submit their local data and analysis to cross-cultural comparisons. We endeavor to begin from an emic perspective—that is, to understand the local community on its own terms. But the anthropological commitment to understanding human diversity and the complexity of human cultures also requires taking an etic perspective—viewing the local community from the anthropologist’s perspective as an outsider. This provides a foundation for comparison with other relevant case studies. The overarching process of comparison and assessment, called ethnology, uses the wealth of anthropological studies to compare the activities, trends, and patterns of power across cultures. The process enables us to better see what is unique in a particular context and how it contributes to identifying larger patterns of cultural beliefs and practices. Perhaps the largest effort to facilitate worldwide comparative studies is the Human Relations Area Files at Yale University (http://hraf.yale.edu/), which has been building a database of ethnographic material since 1949 to encourage cross-cultural analysis.

Glossary

- anthropologist’s toolkit The tools needed to conduct fieldwork, including information, perspectives, strategies, and even equipment.

- quantitative data Statistical information about a community that can be measured and compared.

- qualitative data Descriptive data drawn from nonstatistical sources, including personal stories, interviews, life histories, and participant observation.

- rapport Relationships of trust and familiarity that an anthropologist develops with members of the community under study.

- key informant A community member who advises the anthropologist on community issues, provides feedback, and warns against cultural miscues. Also called cultural consultant.

- life history A form of interview that traces the biography of a person over time, examining changes in the person’s life and illuminating the interlocking network of relationships in the community.

- survey An information-gathering tool for quantitative data analysis.

- kinship analysis A fieldwork strategy of examining interlocking relationships of power built on marriage and family ties.

- field notes The anthropologist’s written observations and reflections on places, practices, events, and interviews.

- mapping The analysis of the physical and/or geographic space where fieldwork is being conducted.

- built environment The intentionally designed features of human settlement, including buildings, transportation and public service infrastructure, and public spaces.

- zeros Elements of a story or a picture that are not told or seen and yet offer key insights into issues that might be too sensitive to discuss or display publicly.

- mutual transformation The potential for both the anthropologist and the members of the community being studied to be transformed by the interactions of fieldwork.

- emic An approach to gathering data that investigates how local people think and how they understand the world.

- etic Description of local behavior and beliefs from the anthropologist’s perspective in ways that can be compared across cultures.