KEYCONCEPT QUESTION

3.4 Counter the following argument: “Exaptations are common; therefore, natural selection is not nearly as important as many biologists have claimed.”

Ever since Darwin published On the Origin of Species, evolutionary biologists have been fascinated by how, in the absence of foresight, natural selection can create complex traits with many interdependent components.

How, for example, can we explain the exquisite complexity and detail of the human eye? How can we explain the production of milk in mammals and the associated nursing behaviors that make it such a valuable strategy for parental care? And how do we account for the coupling of wing geometry and variable wing angle that allows a dragonfly to produce the high-lift wing-tip vortices that confer its remarkable flight abilities (Thomas et al. 2004)?

In this section, we will examine two possible explanations for the evolution of such complex traits. The first explanation centers on the idea that each intermediate step on the way toward the evolution of complex traits was itself adaptive and served a function similar to the modern-day function. The second explanation—co-option of a trait to serve a new purpose—posits that intermediate stages of complex traits were functional and selected, but they did not serve the same function in the past as they do today.

When looking at an organ as complex as the eye, we are struck by the extraordinary complexity of a trait that requires so many intricate parts, all of which must work together. How could such a complex trait ever evolve in the first place? Darwin raised this issue in On the Origin of Species:

To suppose that the eye, with all its inimitable contrivances for adjusting the focus to different distances, for admitting different amounts of light, and for the correction of spherical and chromatic aberration, could have been formed by natural selection, seems, I freely confess, absurd in the highest possible degree. (Darwin 1859, p. 186)

But Darwin argued that natural selection was responsible for the complexity we see in eyes, and that the evolution of the eye occurred through small successive changes, each of which provided a benefit compared to the last version of the eye. The very next sentence of Darwin’s quote reads,

Yet reason tells me, that if numerous gradations from a perfect and complex eye to one very imperfect and simple, each grade being useful to its possessor, can be shown to exist; if further, the eye does vary ever so slightly, and the variations be inherited, which is certainly the case; and if any variation or modification in the organ be ever useful to an animal under changing conditions of life, then the difficulty of believing that a perfect and complex eye could be formed by natural selection, though insuperable by our imagination, can hardly be considered real. (Darwin 1859, pp. 186–187)

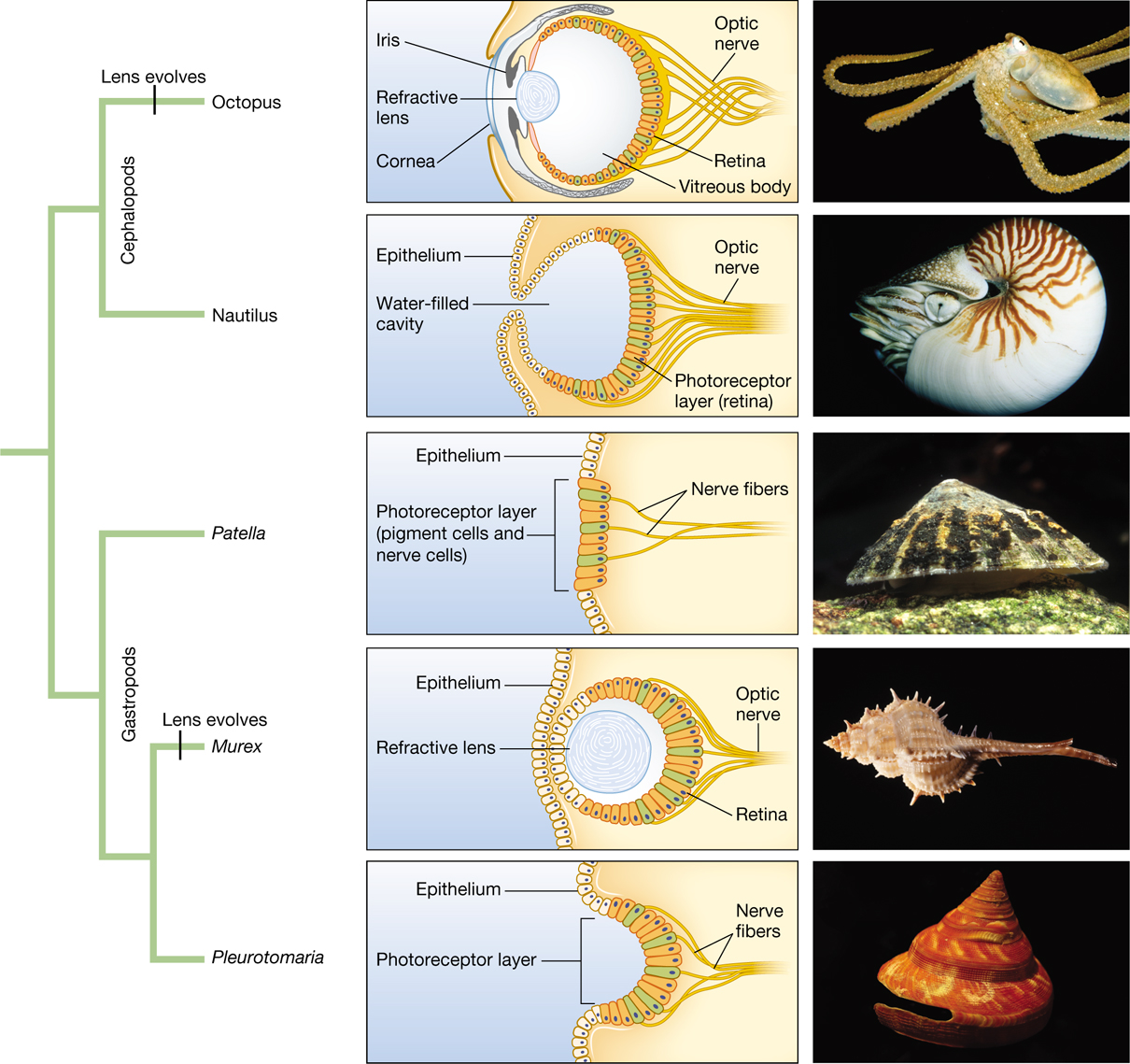

Evolutionary biologists L. V. Salvini-Plawen and Ernst Mayr expanded on Darwin’s hypothesis, laying out a series of intermediate stages that represent one plausible sequence by which the eye evolved in gradual steps (Salvini-Plawen and Mayr 1977). Because eyes are made of soft tissue that does not fossilize well, Salvini-Plawen and Mayr used currently living species to show examples of the sorts of eye morphologies that may have been present in ancestral forms, and they found that indeed current forms can be arranged into a series of steps, each only slightly more complex than the previous, which would lead from a simple light-sensing pigment spot to a focusing eye with a lens. The aim was not to reconstruct the exact sequence by which eye evolution did occur; in fact, there is no single answer to this question because the lensed eye evolved in parallel in several different lineages (Figure 3.20). Rather, this work was meant to illustrate that the focusing eye, elaborate as it may seem, could have evolved in gradual steps, each of which was fully functional and each of which improved on the visual acuity of its predecessor.

An infographic that includes a phylogenetic tree of mollusks, diagrams of their eyes, and images of mollusks corresponding to the diagrams and phylogenetic tree. The mollusk phylogeny splits off into two groups. One is the gastropods and the other is the cephalopods. The cephalopods include the octopus, which have an evolved lens, and the nautilus. The gastropods include the patella, the murex, which have an evolved lens, and the pleurotomaria. The diagram showing the cutout illustration of an octopus’s eye shows that it is composed of a cornea, refractive lens, and an iris at the front. In the back of the eye are the optic nerves and retina. The center of the eye is the vitreous body. The diagram of a Nautilus’s eye shows that it does not have any lens but instead a water-filled cavity. A layer of epithelium covers the surface above and below the opening of the cavity, and also some portions inside of the cavity. The photoreceptor layer (retina) covers the back of the eye where the optic nerves are also located at. The diagram of a Patella’s eye shows an epithelium layer covering the surface, and a small section of the surface is where the photoreceptor layer is also. The photoreceptor layer contains the pigment cells and nerve cells. The nerve fibers connected to this travels further back. The diagram of a Murex’s eye shows that it has an epithelium layer on the outside. It is also composed of a refractive lens in the center and the retina and optic nerves are in the back of the eye. The diagram of a Pleurotomaria’s eye shows that it has an epithelium layer on some of the outside surface, with a photoreceptor layer in the middle which caves in a little. The nerve fibers are located in the back. The images from top to bottom include an octopus, a nautilus, a limpet Patella, a snail Murex, and a snail Pleurotomaria.

But is this feasible? Is there enough time for this to have happened? Dan-Erik Nilsson and Susanne Pelger used computer simulations to explore how long it might take to evolve a focusing eye from a simple light-sensitive patch (Nilsson and Pelger 1994). They assumed that individual mutations had only small phenotypic effects, and they made conservative assumptions about the rate at which natural selection would proceed under these circumstances. They found that the focusing eye could have evolved in fewer than half a million years—a very short time compared to the 550 million years since the first simple eyes occurred in the fossil record.

Darwin’s intuitions seem correct. Complex focusing eyes have evolved by natural selection, and they have done so independently along several lineages on the tree of life. Each of these lineages may have proceeded along a different path, but along each path, every small step could have been functional in itself and could have improved on the visual system that preceded it.

As we mentioned earlier, some traits were originally selected for one function but were later co-opted to serve a different, selectively advantageous function. Such traits are called exaptations (Gould and Vrba 1982; Gould 2002).

As an example, consider the bizarre “helmet” structure that is found in all species of treehopper insects but in no other species (Moczek 2011; Prud’homme et al. 2011) (Figure 3.21). Today, the helmet functions to camouflage treehoppers by mimicking the seeds, thorns, and other structures found in their environment. But how did this novel, complex structure first arise in the treehopper lineage?

A variety of neotropical treehopper insects, each with an elaborate helmet structure. Some looks like horns, others resemble leaves or butterfly wings.

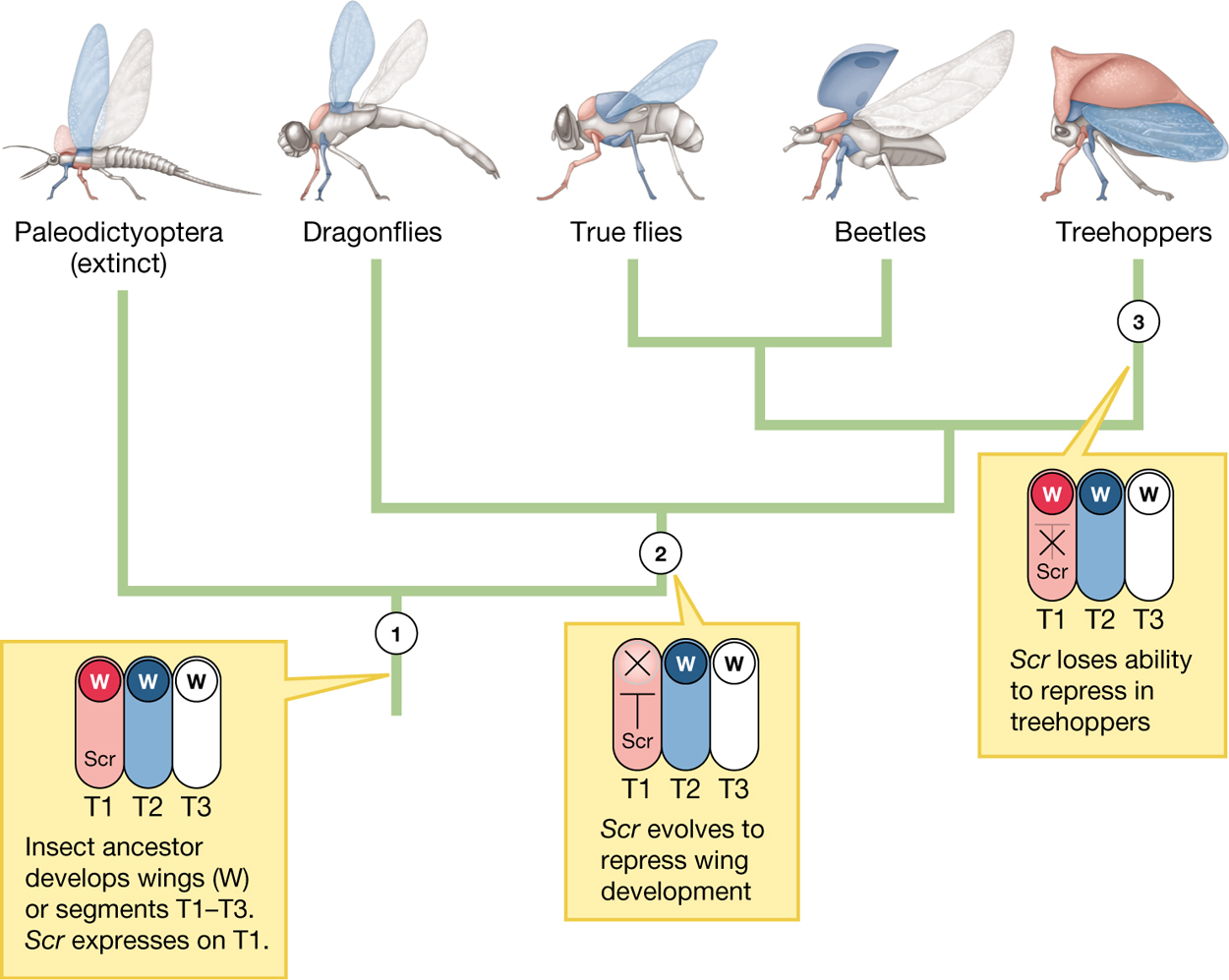

One clue came when Benjamin Prud’homme and his team observed that the helmet forms from paired buds that emerge on the first segment of the treehopper thorax. Other than the helmet structure, the only other appendages known to bud off the first thoracic segment of insects are wings. Although modern insects have wings on only the second and third sections of their thorax, an ancient group of extinct insect species developed small wings on the first thoracic segment as well (Figure 3.22). Along the lineage leading to modern insects, the development of wings on the first thoracic segment was suppressed.

An illustration of an extinct insect, the Stenodyctya lobata. It shows that small wings developed on the first thoracic segment of the insect, along with wings on the second and third segments of the thorax.

Prud’homme’s group wondered whether the developmental pathway that once led to wings on the first thoracic segment (but was then suppressed) could have been co-opted by treehoppers to produce their distinctive helmet structures. They found several pieces of evidence supporting their hypothesis. From an anatomical perspective, helmets are built in a way reminiscent of the way wings are built; for example, the hinges that connect wings to other body parts and the hinges connecting the helmet to other body parts are structurally very similar. Looking at the genetics of development, some of the same genes—in particular the sex comb reduced, or Scr, gene—are involved both in wing development and in helmet development (Figure 3.23), and recent work comparing the genomes of treehoppers and their close relatives further links genes associated with wing development to the origin of helmets (Fisher et al. 2020). The helmet in treehoppers appears to be an exaptation: The original trait “wings on the first thoracic segment” was suppressed in the lineage leading to modern insects, but subsequently this developmental pathway was co-opted in the treehopper lineage to produce the helmet.

A phylogenetic tree showing the development of wings and helmets in insects. The tree splits off into five groups which include: the Paleodictyoptera (extinct), dragonflies, true flies, beetles, and treehoppers. At lineage 1, the insect ancestor developed wings on segments T1 to T3. S c r expresses on T1. At lineage 2 the S c r evolves to repress wing development. At lineage 3 the S c r loses the ability to repress in treehoppers.

The helmet in treehoppers is just one example of an exaptation and innovation associated with insect wings. Horns in scarab beetles (scarabaeine) are another: Genes associated with serial wing formation—genes that may have predated the evolution of insects—are essential for the development of horns on the thorax of three scarab beetles species (Onthophagus sagittarius, O. taurus, and O. binodis). When Yonggang Hu and colleagues used molecular genetic tools to interfere with gene expression in a number of genes known to be critical to wing development, this stunted not just wing development, but horn development as well (Hu et al. 2019) (Figure 3.24).

Exaptations play an important role in the evolution of complex traits. Any time a trait adopts a new function over evolutionary time, it is an exaptation. Gross morphological structures rarely arise de novo, but instead derive from modifications to previously existing structures. The same can be said of molecular structures, as we will see in the next subsection. As a result, most complex traits will have extensive evolutionary histories over which they have undergone multiple changes in function, and thus such traits will represent a “layering of adaptations and exaptations” (Thanukos 2009).

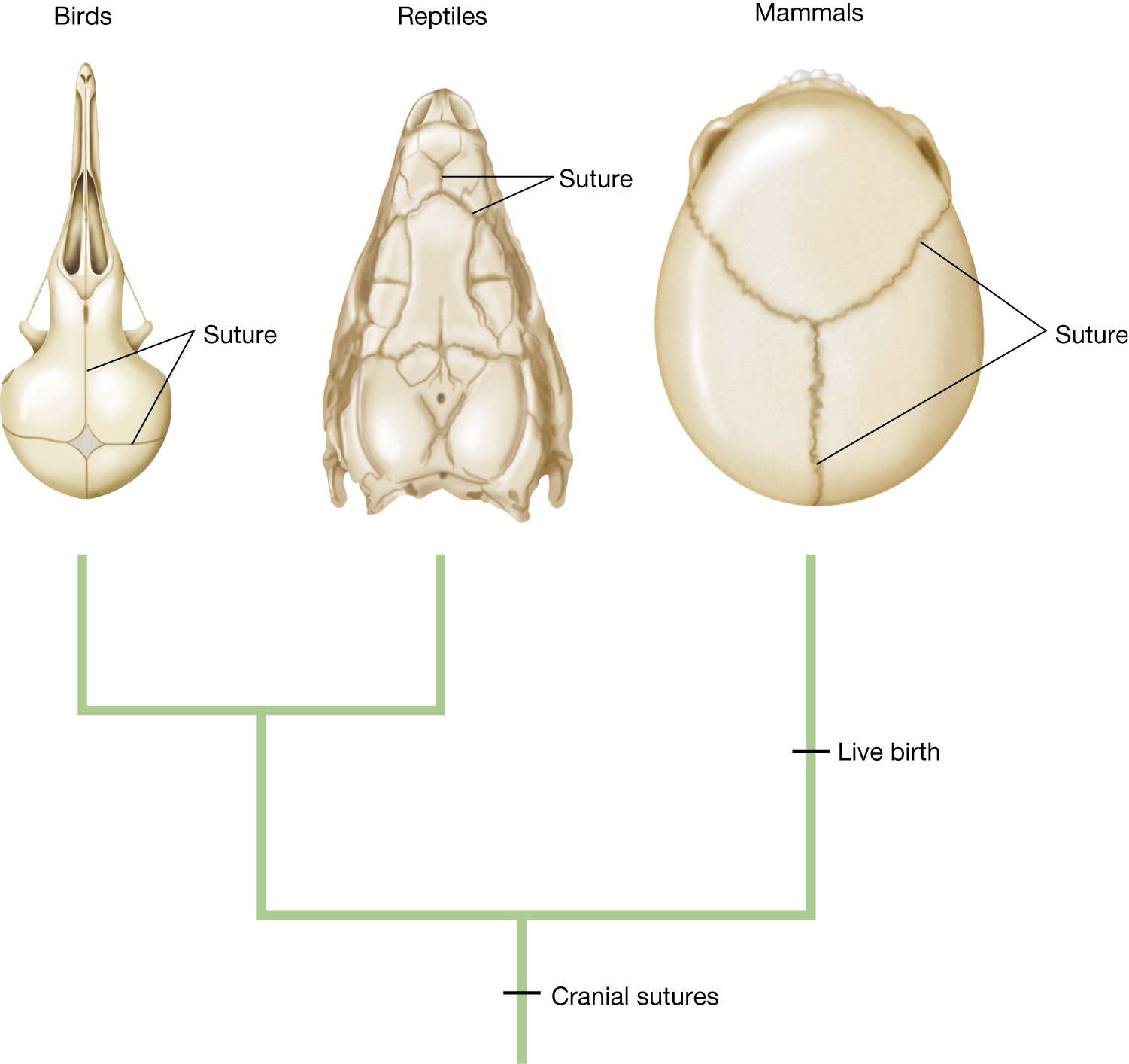

Although the term exaptation was not introduced until 1982 by Stephen Jay Gould and Elizabeth Vrba, Darwin was aware of this phenomenon in On the Origin of Species, in which he wrote, “The sutures in the skulls of young mammals have been advanced as a beautiful adaptation for aiding parturition, and no doubt they facilitate, or may be indispensable for this act” (Darwin 1859, p. 197). In this passage, Darwin described cranial sutures, the fibrous connective tissue joining the bones that make up the skull. Because the bones of the skull are not yet fused at birth and because the sutures are relatively elastic, the skull is able to deform somewhat as it passes through the birth canal during parturition (the process of giving birth). Although cranial sutures may serve to aid the process of live birth in modern times (particularly in humans, where cranium diameter is a major constraint on size at birth), it need not have been the original function of sutures. Indeed, it was not the original function, Darwin argued. He immediately followed the above statement with “sutures occur in the skulls of young birds and reptiles, which have only to escape from a broken egg,” (Darwin 1859, p. 197). Cranial sutures could not have evolved to aid the birth process in mammals, as they predated the evolution of mammalian reproduction (Figure 3.25). The original function of cranial sutures was probably to allow the rigid protective cranium to expand with a growing brain, and indeed this function is retained (Yu et al. 2004). Only subsequent to the original function, once live birth evolved, were sutures co-opted to facilitate passage through the birth canal (Darwin 1859). Despite Darwin’s usage of the word adaptation in his original description, in modern terminology, these sutures are exaptations with respect to aiding the mammalian birth process.

A phylogenetic tree that shows cranial sutures predated live birth. At the top are images of a bird skull, a reptile skull, and a mammal skull. The lines in the skulls indicate the sutures. The tree shows that cranial sutures evolved prior to the split between birds, reptiles, and mammals. Live birth evolved in mammals after the split into birds, reptiles, and mammals.

Let’s now consider feathers in modern-day birds, another complex trait that is an example of an exaptation. As we mentioned earlier this chapter, feathers play such a prominent role in bird flight and because they seem so exquisitely suited for that function, we may be tempted to assume that feathers have always been selected only in relation to their effect on flight.

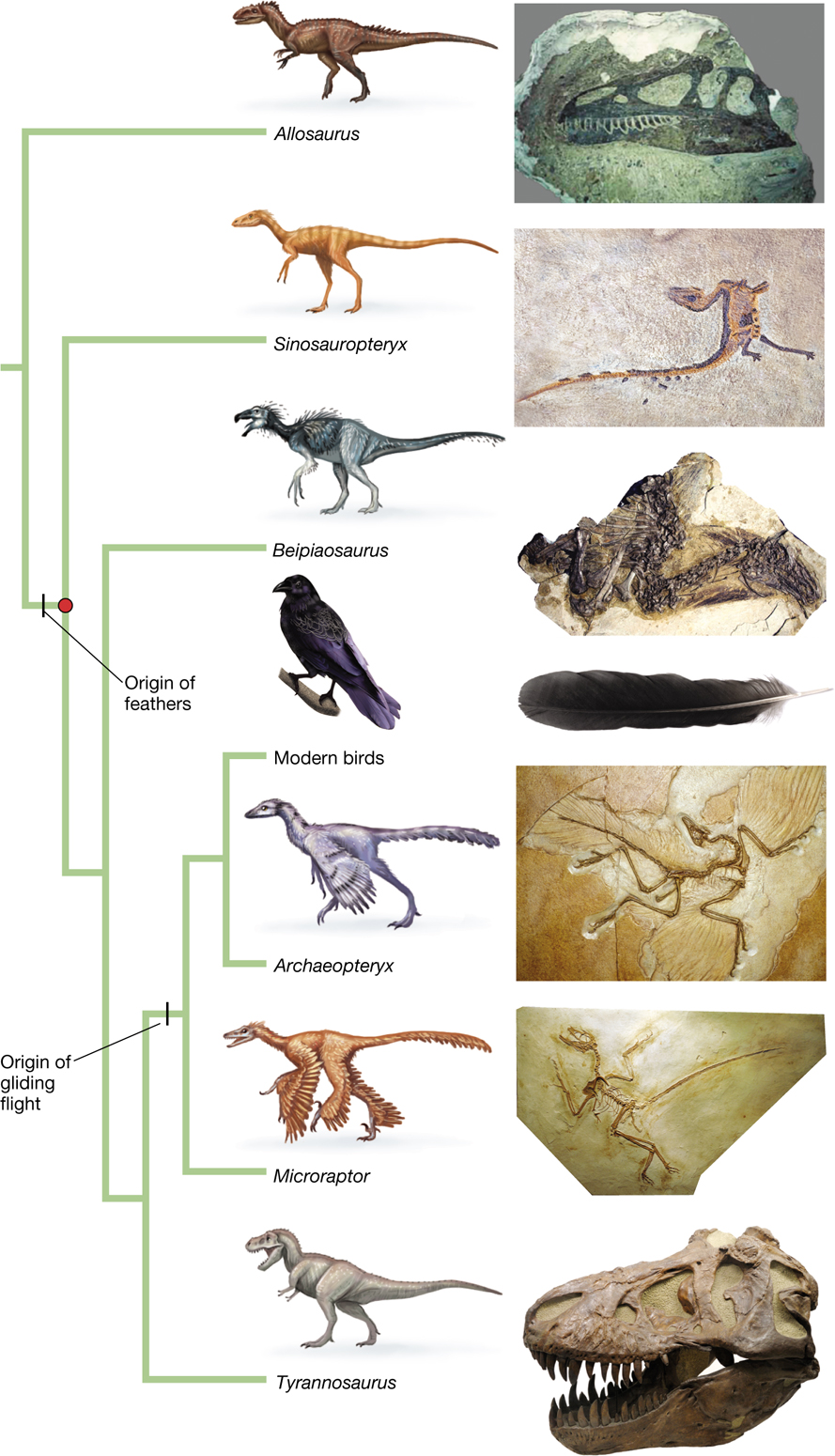

But again, as with Darwin’s example of skull sutures, phylogenetic evidence is useful for separating adaptation from exaptation (Figure 3.26). Paleontological discoveries from northeastern China have revealed that featherlike structures were widespread in a substantial subgroup of the bipedal theropod dinosaurs, which did not use these structures for flight. These dinosaurs ultimately gave rise to modern birds (Ji et al. 1998; Xu et al. 2001, 2009, 2010). Moreover, structural studies strongly suggest a single evolutionary origin of feathers. From this, we can deduce that the origin of feathers predates the evolution of wings and flight.

A phylogenetic tree showing the evolutionary origin of feathers. The tree splits into seven groups which include the following: Allosaurus, Sinosauropteryx, Beipiaosaurus, modern birds, Archaeopteryx, Microraptor, and Tyrannosaurus. Above these names are illustrations of the animal and beside it are images of fossils for the corresponding animal. The origin of feathers is marked by a dash on the phylogenetic tree and the common ancestor of these feathered dinosaurs (including birds) is marked with a solid circle. The lineage within the origin of feathers included all of the species except for the allosaurus. The lineage within the origin of gliding flight included: modern birds, archaeopyeryx, and microraptor.

In light of the phylogenetic evidence that feathers evolved prior to flight, it would be a mistake to conclude that feathers originally evolved as an adaptation for flying. Natural selection cannot look ahead to fashion a structure that only later will become useful. Biologists Richard Prum and Alan Brush offer an appealing analogy: They say that, in light of the phylogenetic evidence, “Concluding that feathers evolved for flight is like maintaining that digits evolved for playing the piano” (Prum and Brush 2002, p. 286).

So, what might have been the original function, or perhaps functions, of feathers? Over the years, researchers have proposed several possibilities, including (1) retaining heat, (2) shielding from sunlight, (3) signaling, (4) facilitating tactile sensation, as whiskers do, (5) prey capture, (6) defense, (7) waterproofing, and (8) brooding eggs (Prum and Brush 2002; Zelenitsky et al. 2012).

Using the arguments we developed earlier, we can say that the basic structure of feathers is, in part, an exaptation with respect to bird flight. That does not mean that feathers, once selected for their initial function, were not subsequently shaped by natural selection because of the fitness effects associated with flight in birds. Rather, once selected for thermoregulation or other purposes, any changes to feathers that also made them more beneficial for early flight would likely have been selected.

Notice that when a trait switches function, the organism need not lose the original function. Sometimes the trait can serve both purposes. Skull sutures facilitate brain growth and aid parturition. Feathers can serve both to insulate the bird and to facilitate flight.

Next, we will consider two examples of how novelty arises at the molecular level.

Whether at the morphological level or at the level of individual molecules, the process of evolution is ever tinkering with extant structures. One way that new molecular functions can arise is through the process of gene sharing, in which a protein that serves one function in one part of the body is recruited to perform a new and different function in a second location.

There is no better illustration of the breadth and diversity of gene sharing than the lens crystallin proteins. Lens crystallins are structural proteins that form the transparent lens of the eye. Although some lens crystallins are used only in the lens, many are dual-function proteins that are also used as enzymes elsewhere in the body. Table 3.1 lists a number of the lens crystallins that also function as enzymes.

|

TABLE 3.1 |

||

|

Examples of Gene Sharing: Lens Crystallins with Separate Enzymatic Functions |

||

|

Crystallin |

Species |

Enzyme |

|

δ |

Birds and reptiles |

Argininosuccinate lyase |

|

ε |

Birds and crocodiles |

Lactate dehydrogenase D4 |

|

τ |

Lamprey, fish, reptiles, and birds |

α-Enolase |

|

λ |

Rabbit |

Hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase |

|

ζ |

Guinea pig |

Alcohol dehydrogenase |

|

α |

Vertebrates |

Small heat shock protein homologs |

|

Ω |

Cephalopods |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase homolog |

|

Adapted from Piatigorsky and Wistow (1989) and Piatigorsky 2003 |

||

The process of gene duplication provides another evolutionary pathway by which a protein can switch functions without loss of the original function. In a gene duplication event, an extra copy of a functional gene is formed. Once an organism has two copies of the gene, one of the two gene copies might change to a new function, while the other can remain unchanged and thus preserve the original function. We conclude this subsection with one such example (and return to gene duplication in other subsequent chapters as well).

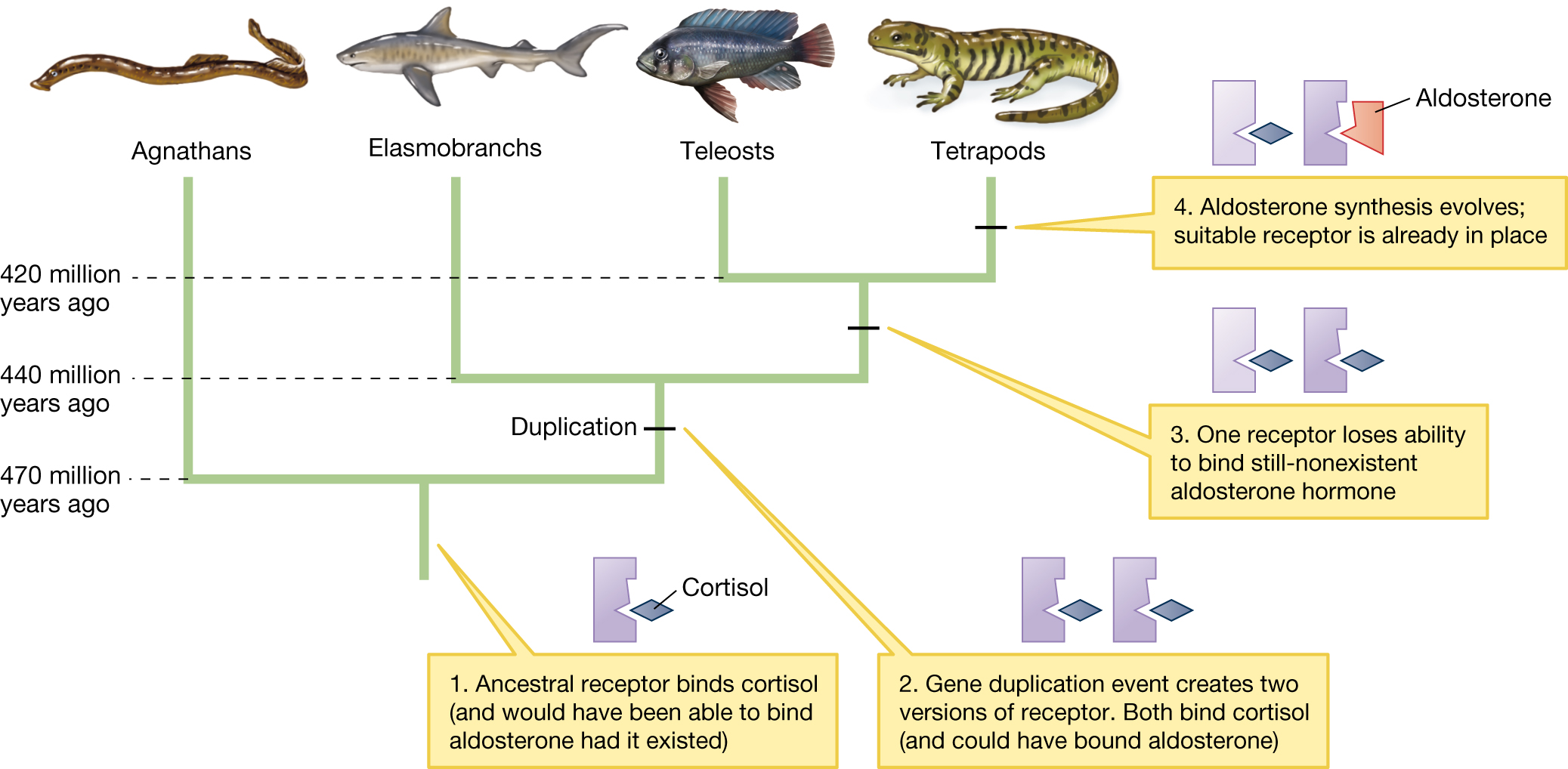

One particularly complex suite of traits is the lock-and-key mechanism of many hormone–receptor pairs, with their exquisite specificity (Figure 3.27). These hormone–receptor pairs pose a chicken-and-egg problem: How could a signaling protein possibly evolve to match a receptor that has not yet arisen; or, conversely, how could a receptor evolve to accept a signal that does not yet exist?

A diagram showing a lock-and-key system. A receptor attached to the cell membrane has a binding site on the outside. Inside the cell membrane is the cell interior. A signaling molecule begins to float over to bind to the receptor. Once the signaling molecule binds to the receptor, a chain of reactions is set off towards the cell interior and beyond, altering the activity of the cell.

Jamie Bridgham and her colleagues worked out a detailed answer to this question for one such lock-and-key pair: the mineralocorticoid receptor (let’s call it the M receptor) and the steroid hormone called aldosterone, which triggers this receptor (Bridgham et al. 2006, 2009). The M receptor, which is involved in controlling the electrolyte balance within cells, arose in a gene duplication event from an ancestral glucocorticoid receptor.

But how did this gene duplication lead to a novel and highly specific aldosterone–M receptor pair? Again, a phylogenetic approach was the key to unraveling this mystery. By sequencing the mineralocorticoid receptor genes from a wide range of vertebrates, Bridgham’s team was able to infer the genetic sequence of the ancestral receptor that was duplicated to produce both the M and modern glucocorticoid receptors. (In the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, evolutionary biologists have not only reconstructed ancestral proteins, but inserted them into transgenic animals; Siddiq et al. 2017).

Bridgham and her colleagues found that the ancestral receptor binds not only cortisol (a glucocorticoid hormone) but also aldosterone. This finding is surprising because it means that the ancestral receptor could bind a hormone that didn’t exist when the ancestral receptor was in place—aldosterone evolved much later. But cortisol was already in existence at the time of the ancestral receptor. Evolutionary biologists have hypothesized that after the gene duplication, a pair of mutations altered the shape of one of the receptors—what is now the glucocorticoid receptor—so that it retained its ability to bind cortisol but would no longer bind aldosterone. At the time, aldosterone wasn’t present yet, but over millions of years, genetic changes in biosynthetic pathways (associated with cytochrome P-450) by chance eventually led to the production of aldosterone. Because aldosterone could now trigger the M receptor without interfering with the glucocorticoid receptor, there was a new signal–receptor pair that could be used independently to regulate other cellular processes. Now we know which came first in this chicken-and-egg problem. The ability of the receptor to bind aldosterone preceded the evolution of aldosterone itself (Figure 3.28).

A phylogenetic tree showing gene duplication and the evolution of the aldosterone receptor. The tree splits into four groups which include the following: Agnathans, Elasmobranchs, Teleosts, and Tetrapods. At the first lineage, 470 million years ago, the ancestral receptor binds cortisol (and would have been able to bind aldosterone had it existed). At the second lineage, 440 million years ago, a gene duplication event creates two versions of the receptor. Both bind cortisol (and could have bound aldosterone). At the third lineage, about 420 million years ago, one receptor loses its ability to bind the still-nonexistent aldosterone hormone. The branch that splits at 420 million years ago leads to the teleosts and the tetrapods. In the tetrapods, the aldosterone synthesis evolves and the suitable receptor is already in place.

KEYCONCEPT QUESTION

3.4 Counter the following argument: “Exaptations are common; therefore, natural selection is not nearly as important as many biologists have claimed.”