Volume

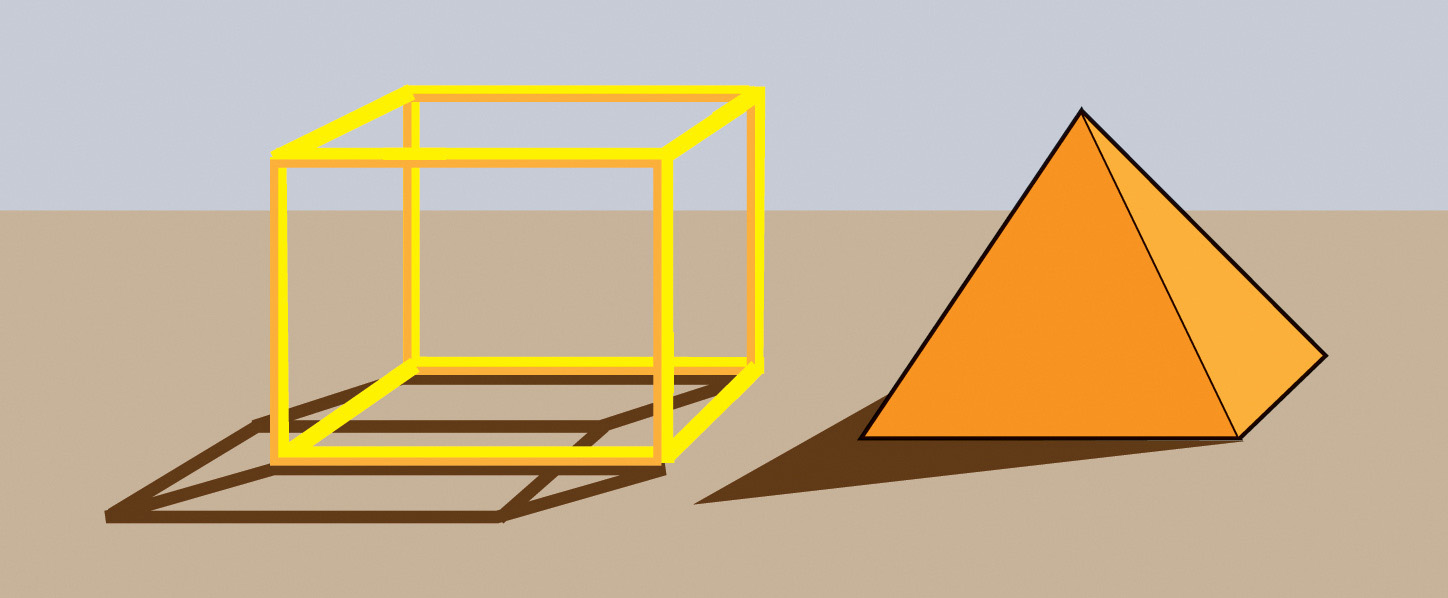

1.2.9 Volume (left) and mass (right)

Three-dimensional objects necessarily have volume. Volume is the amount of space occupied by an object. Solid objects have volume; so do objects that enclose an empty space. Mass, by contrast, suggests that something is solid and occupies space (1.2.9). Architectural forms usually enclose a volume of interior space to be used for living or working. For example, some hotel interiors feature a large, open atrium that becomes the focal point of the lobby. Some sculptures accentuate weight and solidity rather than openness. Such works have very few open spaces that we can see. The presence of mass suggests weight, gravity, and a connection to the Earth. The absence of mass suggests lightness, airiness, flight. Asymmetrical masses—or masses that cannot be equally divided on a central axis—can suggest dynamism, movement, change.

Open Volume

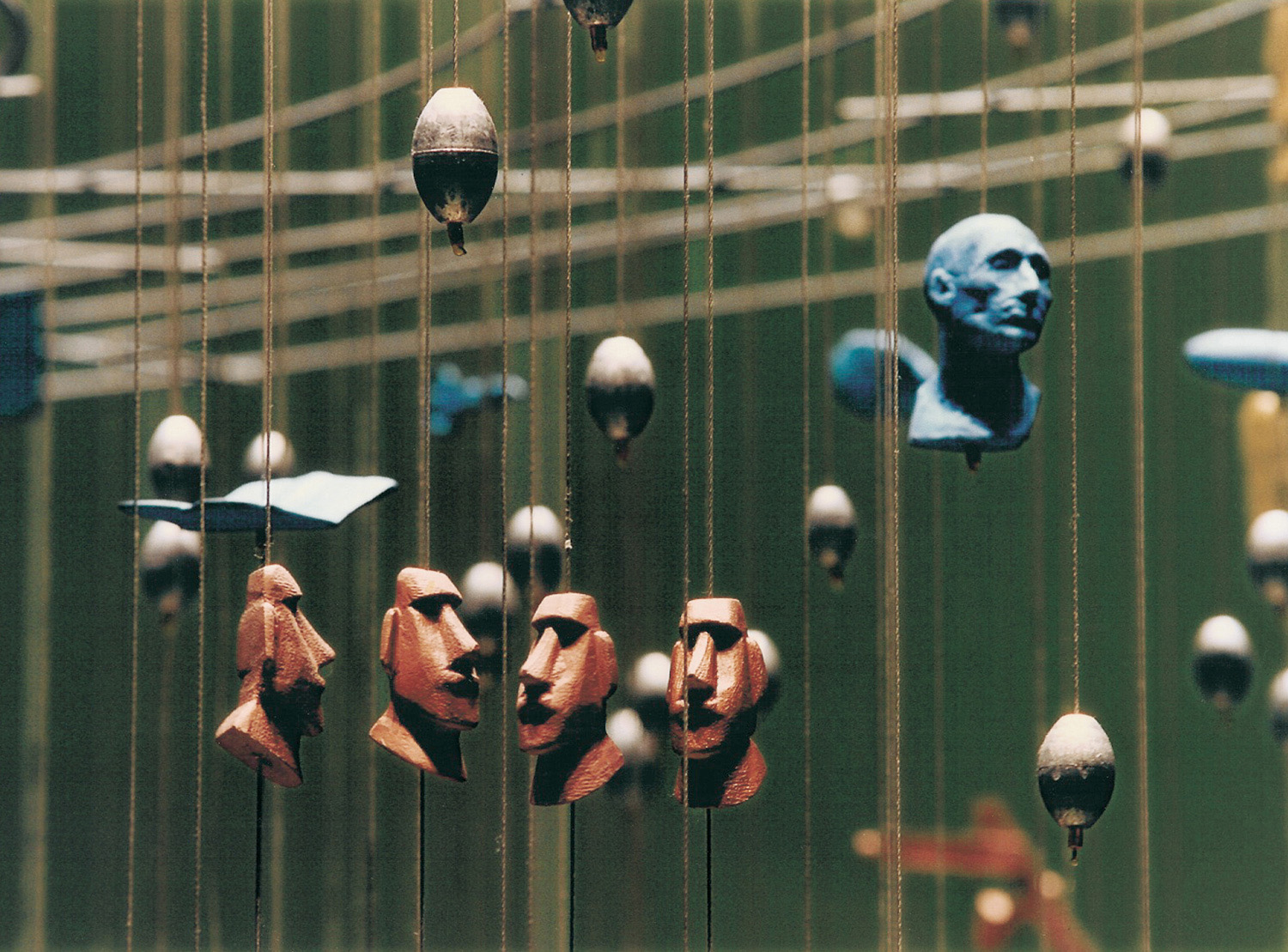

When artists enclose a space with materials that are not completely solid, they create an open volume. In Ghostwriter, Ralph Helmick (b. 1952) and Stuart Schechter (b. 1958) use carefully suspended pieces of metal to make an open volume that, when looked at as a whole, creates the image of a large human head (1.2.10a and 1.2.10b). The small metal pieces, which represent letters of the alphabet, little heads, and other objects, are organized so that they delineate the shape of the head but do not enclose the space. In the stairwell where the piece hangs, the empty space and the “head” are not distinct or separate, but the shape is nonetheless implied.

1.2.10a Ralph Helmick and Stuart Schechter, Ghostwriter, 1994. Cast metal/stainless cable, 36 × 8 × 10'. Evanston Public Library, Illinois

1.2.10a Ralph Helmick and Stuart Schechter, Ghostwriter, 1994. Cast metal/stainless cable, 36 × 8 × 10'. Evanston Public Library, Illinois

1.2.11 Vladimir Tatlin, Model for Monument to the Third International, 1919

The Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin’s (1885–1953) Monument to the Third International was intended to be a huge tower housing the offices and chamber of delegates of the Communist International. It was going to commemorate the triumph of Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution. Never built, it would have been much higher than the Eiffel Tower in Paris, France. In its planned form, the spiraling open volume of the interior, and its proposed novel use of such materials as steel and glass, symbolize the modernism and dynamism of Communism (1.2.11). Tatlin believed that art should support and reflect the new social and political order.

Open volume can make a work feel light. In the Blue (Crest), a collaborative work by American sculptors Carol Mickett (b. 1952) and Robert Stackhouse (b. 1942), was created to imply the presence of water (1.2.12). By creating negative space (the openings between the wooden slats) with crowds of horizontal struts, the artists make the work seem to float. Mickett and Stackhouse also curve the pieces and place them at irregular intervals to create many subtle changes in direction. This arrangement gives a feeling of motion, like the gentle ripples of flowing water. The artists hope that viewers will experience a sensation of being surrounded by water as they walk through the passage.

1.2.12 Carol Mickett and Robert Stackhouse, In the Blue (Crest), 2008. Painted cypress, 24 × 108 × 11'. Installation at St. Petersburg Art Center, Florida

1.2.12 Carol Mickett and Robert Stackhouse, In the Blue (Crest), 2008. Painted cypress, 24 × 108 × 11'. Installation at St. Petersburg Art Center, Florida

Negative space, like that used in In the Blue (Crest), illustrates the importance of leaving areas of a work “visually empty.” These openings allow light to become a more active part of the work by adding light and dark contrasts. Negative space is also common in two-dimensional work, but instead of allowing light to play a more active role, the emptiness contrasts with the positive shapes and lines.