![]() English Settlers' Inspiration

English Settlers' Inspiration

What were the major patterns of Native American life in North America before Europeans arrived?

AN OLD WORLD: NORTH AMERICA

The most striking feature of Native American society at the time Europeans arrived was its diversity. Each group had its own political system, religious beliefs, and language. Indians did not think of themselves as a single people, and Native Americans still today identify primarily as separate nations. Identity centered on a family, clan, town, nation, or confederacy. When Europeans first arrived, many Indians saw them as simply one group among many. Their first thought was how to use the newcomers to enhance their standing in relation to other Native peoples. The sharp dichotomy between “Indians” and “white” persons did not emerge until later in the colonial era.

The Settling of the Americas

During the Ice Age, tens of thousands of years ago, bands of hunters and fishers crossed the Bering Strait via a land bridge. Others arrived by sea from Asia or the Pacific islands earlier or later than the Bering migrants. Some Native American creation stories tell of migrations, but others describe creations within the Americas, of ancestors who fell from the sky or came into the world from a hollow log.

However people got there originally, the Americas were an ancient homeland to Native Americans by the time Europeans arrived. The hemisphere had witnessed many changes during its human history. First, the early inhabitants and their descendants spread across the two continents. Around 9,000 years ago, at the same time that agriculture was being developed in Mesopotamia, it also emerged in modern-day Mexico and the Andes and then spread to other parts of the Americas. Maize (corn), squash, and beans formed the basis of agriculture.

THE ATLANTIC WORLD, ca. 1300

The Americas, Western Europe, and West Africa on the eve of colonization. There were countless human settlements on all four continents. People lived on farms, in villages and towns, and in cities, including the cities marked on the map.

Politics and Power in Native North America

The Medieval Warm Period that began around the year 950 allowed the expansion of agriculture and the rise of cities in North America, much as it did in Europe and West Africa. The longer growing seasons and more predictable weather of the era were ideal for farming, and large-scale farming made urban living possible. The largest city north of Mexico was Cahokia, across the Mississippi River from what is now St. Louis. In the year 1200, Cahokia’s central city was home to some 12,000 people, plus a large population in outlying cities, towns, and farms. Cahokia influenced other people to build their own cities and accompanying dependent provinces—what archaeologists call “Mississippian civilizations.” Mississippian leaders ruled their realm from large halls, temples, and council chambers built on top of a central mound.

Ancestors of Native peoples of the arid Southwest, including the Ancestral Puebloans and the Huhugam, constructed elaborate irrigation systems to farm in the desert. They built great planned towns with large multifamily dwellings, and they conducted long-distance trade. Pueblo Bonito, in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, stood five stories high and had more than 600 rooms. As with the Mississippians, an elite class of leaders arose.

The Medieval Warm Period ended around 1250, and the Little Ice Age began. Large-scale agriculture and cities became harder to sustain. Oral histories and archaeological evidence indicate a period of growing distrust in powerful leaders and centralized political systems. People moved out of Mississippian and southwestern cities into smaller-scale, more ecologically sustainable towns and farms. When Spanish explorers came to the Southwest, they called some of its people the Pueblo Indians because they lived in towns, or pueblos. Spanish explorers in the sixteenth-century Southeast saw Mississippian cities, but the largest of them had already fallen.

In some places, confederacies formed. In present-day New York and Pennsylvania, five nations—namely, the Mohawks, Oneidas, Cayugas, Senecas, and Onondagas—formed a Great League of Peace. They called their league the Haudenosaunee, “the people of the longhouse.” (Their enemies called them the Iroquois, which meant something like “snakes.”) Each year the Haudenosaunee Great Council, with male representatives chosen by the women of the five nations, met to coordinate dealings with outsiders. In the Southeast, the Choctaw, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Catawba nations each eventually united dozens of towns in loose alliances.

More information

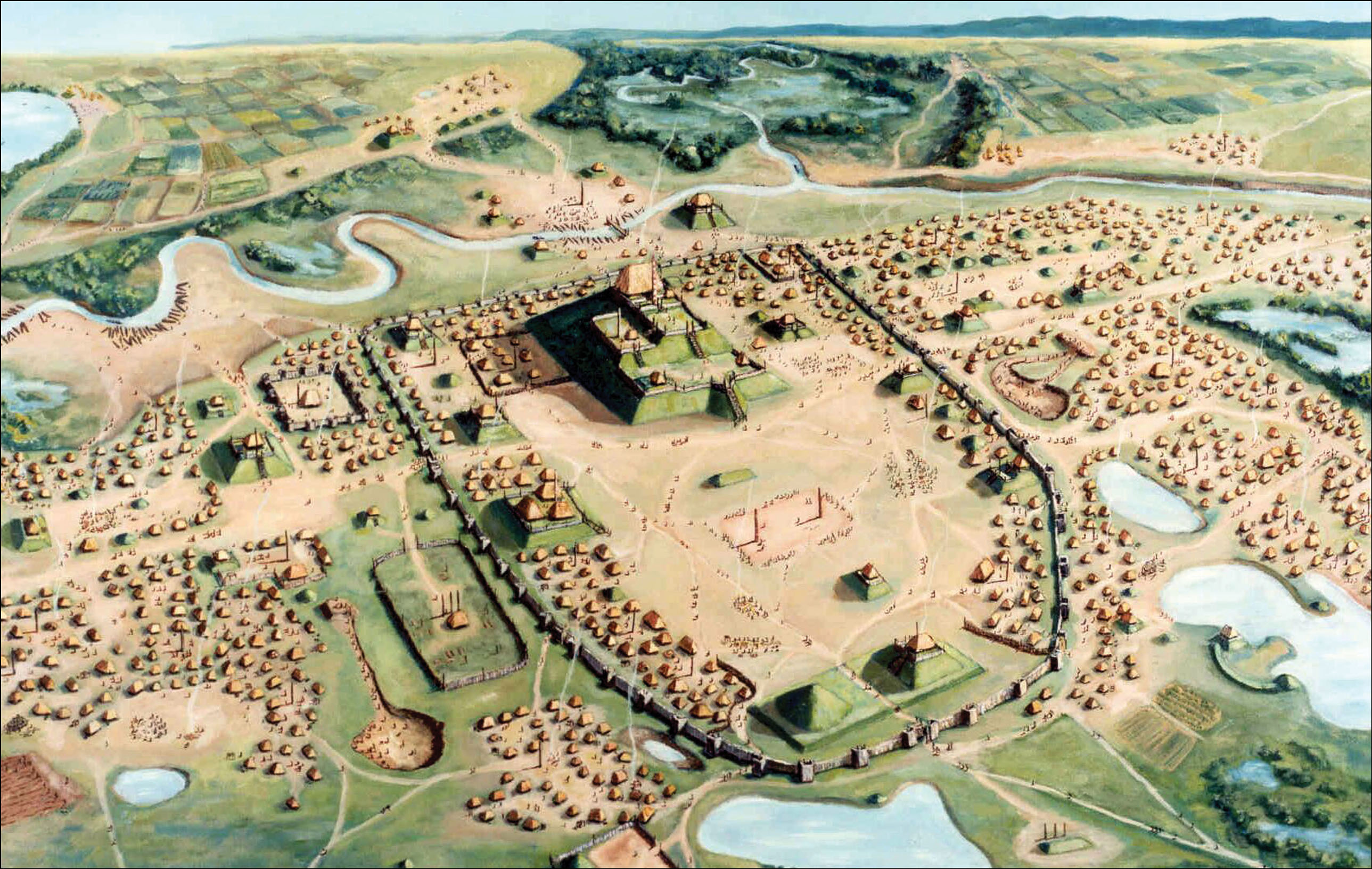

A painting showing what the Native American urban center of Cahokia may have looked like. In the center is the main enclosure; it contained mounds, small dwellings, two sundials, and many pathways. Surrounding the enclosed part of the city there are more dwellings and many ponds. In the distance there is a winding river that separates the city from farmlands and mountains.

A modern visualization of Cahokia in the Mississippi River Valley, the largest Native American urban center in what is now the United States.

Economics and Trade in Native North America

By the 1500s, Native leaders generally led through persuasion and reciprocity. A successful leader needed to have connections to outsiders and the ability to trade and make alliances with foreign peoples, thus bringing in valuable goods and ideas.

Exchange networks crossed North America, carrying local goods such as food, plant dyes and medicines, and pottery. These networks also distributed goods from far away, including shell beads from the coasts and copper from the Great Lakes region.

In eastern North America, hundreds of peoples inhabited towns and villages scattered from the Gulf of Mexico to present-day Canada. They lived on corn, squash, and beans, supplemented by fish, deer, turkeys, and other animals. On the densely populated Pacific coast, hundreds of distinct groups resided in independent villages and lived primarily by fishing and gathering wild plants and nuts. On the Great Plains, with its herds of buffalo, many groups were hunters (who tracked animals on foot before the arrival of horses with the Spanish) part of the year, living in agricultural communities the rest of the time.

Numerous land systems existed among Native Americans. Generally, families or towns had the right to farm on certain lands, and nations or confederacies claimed specific areas for hunting, fishing, and gathering. Indians saw land as a resource that particular people had the right to use but not as an economic commodity that could be bought and sold.

Leaders tended to come from certain families or clans, and they often controlled access to resources. But their reputation and influence rested on their ability to distribute goods to their followers. Generosity was among the most valued qualities. Under normal circumstances no one in Native societies went hungry or experienced the extreme inequalities of Europe. “There are no beggars among them,” reported the English colonial leader Roger Williams of Indians around New England.

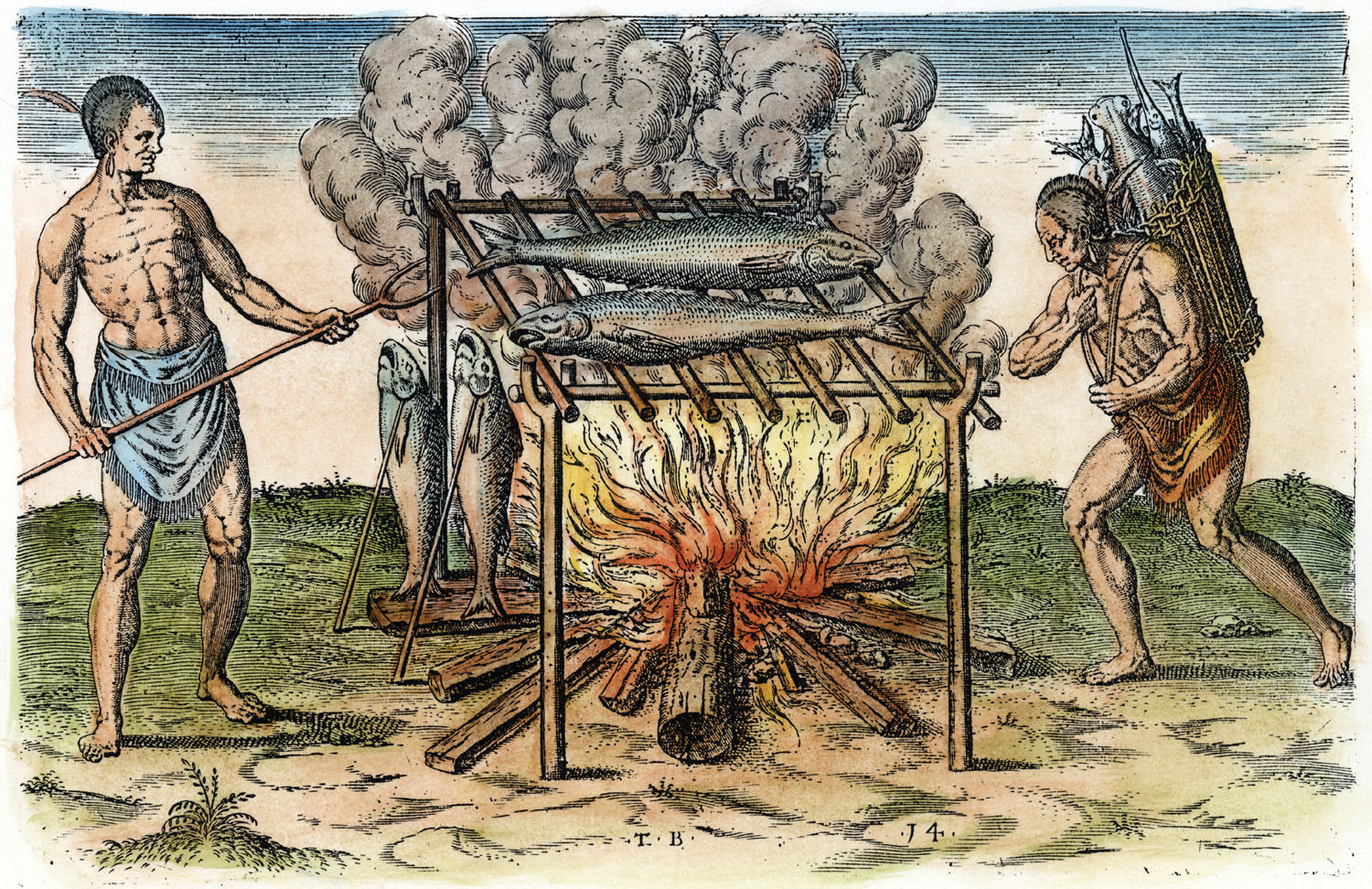

This engraving shows Native men of Ossomocomuck (present-day coastal North Carolina) cooking fish they caught off the Outer Banks.

NORTH AMERICA, ca. 1500

The Native population of North America at the time of first contact with Europeans consisted of numerous peoples and nations with their own languages, religious beliefs, and economic and social structures. This map gives a sense of the large number of nations. By necessity, it leaves many out and includes some names that people did not call themselves in 1500.

More information

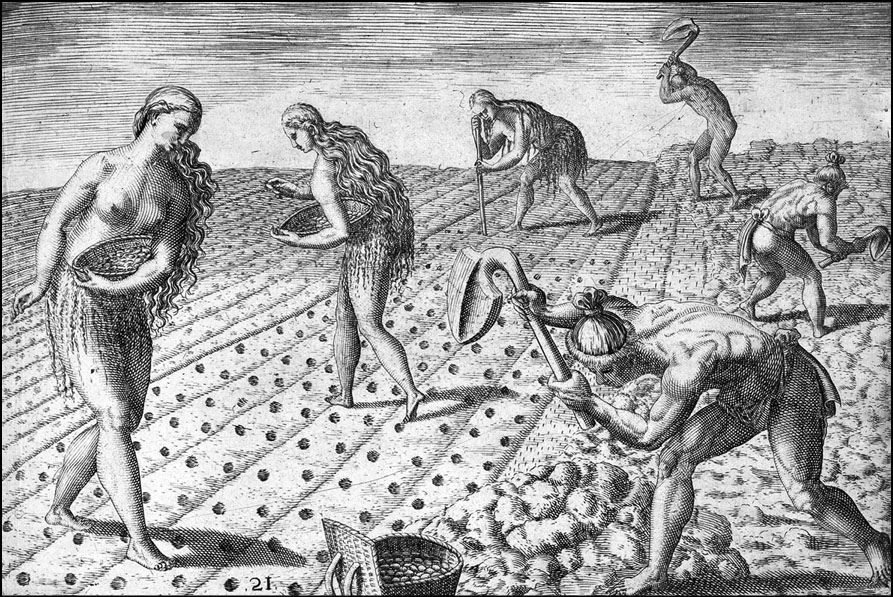

Indian women planting crops while men break the sod. An engraving by Theodor de Bry, based on a painting by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues. Morgues was part of an expedition of French Huguenots to Florida in 1564; he escaped when the Spanish destroyed the outpost in the following year.

Native women planting crops while men break the sod. An engraving by Theodor de Bry, based on a painting by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues. Le Moyne was part of an expedition of French Huguenots to Florida in 1564; he escaped when the Spanish destroyed the outpost in the following year.

Native societies were highly gendered but much more equal than the European system of gender relations. In most Native communities, women had responsibility for farming and running households, including building houses. Women made the decisions about food cultivation, storage, and preparation. They participated in councils, especially regarding matters within the realm of women. Because they provided the food for battle and diplomacy, women participated in decisions about going to war and making peace. Many North American societies were matrilineal—that is, tracing descent through the mother’s line. Women generally had some power over their own sexuality and marriage, including divorce.

Religion in Native North America

For the Native societies of North America, as for people all around the world in the medieval and early modern eras, religion was a system of belief that permeated every aspect of life. Spiritual power, they believed, suffused the world, and sacred spirits could be found in all kinds of living and inanimate things—animals, plants, trees, water, and wind. Through religious ceremonies, they aimed to harness the aid of powerful supernatural forces to secure abundant crops or fend off dangerous spirits. Religious leaders and others who seemed to possess special abilities to invoke supernatural powers held positions of respect and authority.

A major difference with Christianity, as well as with Judaism and Islam, was that Native North American religions were inclusivist. In theory at least, Christians were supposed to be exclusively Christian, rejecting all other religions’ beliefs and practices as heresy. Inclusivist religions, in contrast, allowed adherents to incorporate new religious beliefs and practices as part of a larger effort to make sense of the world. This fundamental difference between inclusivist and exclusivist ways of practicing religion would lead to grave misunderstandings when Christian missionaries tried to convert Native Americans.

Slavery and Freedom in Native North America

![]() Settlers and Indians

Settlers and Indians

Many Europeans saw Indians as embodying freedom. The Haudenosaunee, wrote one colonial official, held “such absolute notions of liberty that they allow of no kind of superiority of one over another, and banish all servitude from their territories.” But most colonizers quickly concluded that the notion of “freedom” was alien to Indian societies. Early English and French dictionaries of Indian languages contained no entry for “freedom” or liberté. Nor, wrote one early trader, did Indians have “words to express despotic power, arbitrary kings, oppressed or obedient subjects.” Of course, Native Americans whose ancestors had been part of Mississippian or other hierarchical societies in previous generations did know about the dangers of excessive power. Unlike Europeans, they had rejected that way of life to develop societies with the kind of freedom that they valued.

In Native societies, although individuals were expected to think for themselves and did not always have to go along with collective decision making, men and women judged one another according to their ability to live up to widely understood ideas of appropriate behavior. Far more important than individual autonomy were kinship ties, the ability to follow one’s spiritual values, and the well-being and security of one’s community. Group autonomy and self-determination, and the mutual obligations that came with a sense of belonging and connectedness, took precedence over individual freedom. The Haudenosaunee League held its leaders and representatives to a high standard: “Their hearts shall be full of peace and good will and their minds filled with a yearning for the welfare of the people.”

More information

The Village of Secoton, a drawing by John White, an English artist who spent a year on the Outer Banks of North Carolina in 1585–1586 as part of an expedition sponsored by Sir Walter Raleigh. A central street links houses surrounded by fields of corn. In the lower part, dancing Indians take part in a religious ceremony.

The Village of Secoton, a drawing by John White. A central street links houses surrounded by fields of corn. In the lower part, dancers take part in a religious ceremony.

Like medieval and early modern people around the globe, many Native North American societies practiced small-scale slavery, mostly the enslavement of war captives. Captives had none of the rights or privileges of members of a society. Ripped from their own societies and families, they could be forced to labor or traded away. But slavery was not inheritable, and captives could become full members of the society that adopted them.

Glossary

- Great League of Peace

- An alliance of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) nations, originally formed at least 400 years ago. Each year the Haudenosaunee Great Council, with male representatives chosen by the women of the five (and later six) nations, met to coordinate dealings with outsiders. The League was a major force in the 1600s and 1700s.