![]() New Ideas of Freedom

New Ideas of Freedom

What impelled European explorers to look west across the Atlantic?

AN OLD WORLD: WESTERN EUROPE

Politics and Power in Western Europe

Europe had been devastated by the ending of the Medieval Warm Period, famine, and the Black Death. It lost as much as half its population over the course of the fourteenth century. Whereas North Americans generally decentralized their societies and rejected authoritarian leaders in response to the crises of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, European monarchies grew in power and size.

Wars and strategic marriages created expansive states, including Portugal, Spain, France, England, and the Holy Roman Empire. They were ruled by dynasties that passed the crown through patrilineal lines of succession. Early modern European societies were extremely hierarchical, with gradations of social status ranging from the king and aristocracy down to the urban and rural poor. Inequality was built into virtually every social relationship. The king claimed to rule by the authority of God. Persons of high rank demanded deference from those below them.

Within families, men exercised authority over their wives and children. In England, the legal doctrine known as “coverture” required that when a woman married, she surrendered her legal identity, which became “covered” by that of her husband. She could not own property or sign contracts in her own name, control her wages if she worked, write a separate will, or, except in the rarest of circumstances, go to court seeking a divorce. The husband conducted business and testified in court for the entire family. He had the exclusive right to his wife’s “company,” including domestic labor and sexual relations.

Everywhere in Europe, family life assumed male dominance and female submission. Indeed, political writers of the sixteenth century explicitly compared the king’s authority over his subjects with the husband’s authority over his family. Both were ordained by God. In Europe, women’s freedoms were dramatically more restricted than in North America or West Africa.

Economics and Trade in Western Europe

As in North America and West Africa, most Western Europeans were farmers. The Medieval Warm Period had allowed them to expand agriculture into previously marginal areas, but the Little Ice Age again contracted farming. When European populations rose after the ravages of the Black Death, the fertile lands of the Americas seemed ideal for feeding the excess people.

Western Europe had only recently connected to the centuries-old trade route that stretched from the Mediterranean, Africa, and the Middle East to South Asia and China. The European conquest of the Americas would begin as an offshoot of the quest for a sea route to the East Indies, the source of the gold, silk, tea, sugar, spices, and other luxury goods that Europeans had come to value.

Religion in Western Europe

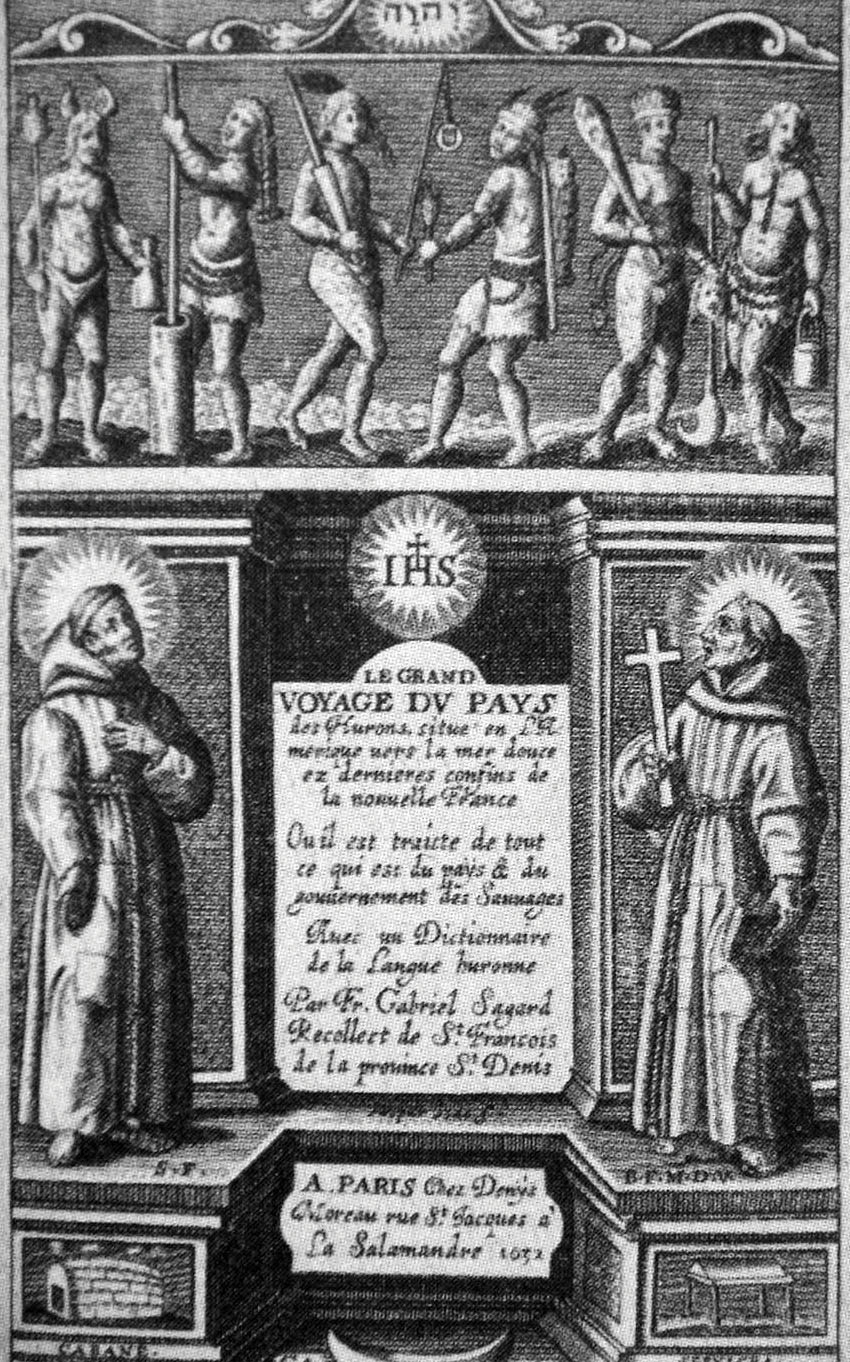

The title page of The Great Voyage to the Country of the Hurons, published in Paris in 1632 by Gabriel Sagard, one of the first missionaries to New France, includes images of Native Americans and Catholic friars. Father Sagard also produced a dictionary of the Huron (Wendat) language.

States in Western Europe had converted to Christianity by the early Middle Ages and were officially Catholic until the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation created Protestantism. As in North America and West Africa, religion was intertwined with daily life. Cathedrals were the centers of towns, and calendars were set by the cycle of church festivals and fast days. Yet, as with Islam in West Africa, older religious traditions survived and blended with Christianity, despite its official theology of exclusivism. Many Europeans continued to believe in witches, demons, and magic.

Commercial and religious motives—namely, the desire to eliminate Islamic intermediaries and win control of lucrative trade for Christian Western Europe—combined to inspire the quest for a direct route to West Africa and Asia. The marriage of King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile in 1469 united their warring kingdoms. In 1492, they completed the reconquista—that is, the “reconquest” of Spain from the Moors, African Muslims who had occupied part of the Iberian Peninsula for centuries. To ensure Spain’s religious unification, Ferdinand and Isabella ordered all Muslims and Jews to convert to Catholicism or leave the country.

Slavery and Freedom in Western Europe

![]() Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Freedoms

Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Freedoms

On the eve of colonization, Europeans held numerous ideas of freedom. Some were as old as the city-states of ancient Greece, while others arose during the political struggles of the early modern era. Some laid the foundations for modern conceptions of freedom, whereas others are quite unfamiliar today. Freedom was not a single idea but a collection of distinct rights and privileges, many enjoyed by only a small portion of the population.

One conception common throughout Europe was that freedom was less a political or social status than a moral or spiritual condition. Freedom meant abandoning the life of sin to embrace the teachings of Christ. “Where the Spirit of the Lord is,” declares the New Testament, “there is liberty.” In this definition, servitude and freedom were mutually reinforcing, not contradictory, since those who accepted the teachings of Christ simultaneously became “free from sin” and “servants to God.”

“Christian liberty” had no connection to later ideas of religious toleration, a notion that scarcely existed on the eve of colonization. Because religious systems of belief permeated every aspect of people’s lives, religion was closely tied to a person’s economic, political, and social position and ability to enjoy basic rights.

Every nation in Europe had an established church that decreed what forms of religious worship and belief were acceptable. Dissenters faced persecution by the state. Religious uniformity was thought to be essential to public order; the modern idea that a person’s religious beliefs and practices are a matter of private choice was almost unknown. The religious wars that racked Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries centered on which religion would predominate in a kingdom or region, not the right of individuals to choose a church.

The equating of liberty with devotion to a higher authority suggested that freedom meant obedience to law. In hierarchical European societies, liberty came from knowing one’s social place and fulfilling the duties appropriate to one’s rank. Most men lacked the freedom that came with economic independence. Even in places where some officials were elected, property qualifications and other restrictions limited the electorate to a minuscule part of the adult male population.

European “liberties” meant formal, specific privileges such as self-government, exemption from taxation, or the right to practice a particular trade, granted to individuals or groups by contract, royal decree, or purchase. One legal dictionary defined a liberty as “a privilege . . . by which men may enjoy some benefit beyond the ordinary subject.” Modern civil liberties did not exist. The government regularly suppressed publications it did not like, and criticism of authority could lead to imprisonment. Personal independence was reserved for a small part of the population. Nonetheless, every European country that colonized the Americas claimed to be spreading freedom—for its own population and for Native Americans.

Slavery was central to the societies of ancient Greece and Rome, and it survived for centuries in northern Europe after the collapse of the Roman empire. Germans, Vikings, and Anglo-Saxons all held slaves. In the Mediterranean world, trade in Slavic peoples survived into the fifteenth century. (The English word “slavery” derives from “Slav.”) The Spanish and Portuguese took Muslim war captives during their reconquista and bought slaves from North African traders. As Europeans began to colonize in the Atlantic, they would look to slavery more and more for labor.

Glossary

- reconquista

- The “reconquest” of Spain from the Moors completed by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492.