![]() Differing Views of Freedom

Differing Views of Freedom

What were the chief features of the Spanish empire in the Americas?

THE SPANISH EMPIRE

By the middle of the sixteenth century, Spain had established an immense empire that reached from Europe to the Americas and Asia. The Atlantic and Pacific oceans, once barriers separating different parts of the world, now became highways for the exchange of goods and the movement of people.

The Spanish empire included the most populous parts of the Americas and the regions richest in natural resources. Stretching from the Andes Mountains of South America through present-day Mexico and the Caribbean and into Florida and the southwestern United States, Spain’s empire exceeded in size the Roman empire of the ancient world. Its center in North America was Mexico City, a magnificent capital built on the ruins of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán that boasted churches, hospitals, and the Americas’ first university. Unlike the English and French empires, Spanish America was essentially an urban civilization. For centuries, its great cities far outshone any urban centers in other colonies and most of those in Europe.

Governing Spanish America

To rule this vast empire, the Spanish crown established a system of government in which authority originated with the king and flowed downward through the Council of the Indies—the main body in Spain for colonial administration—and then to local officials in America. The Catholic Church also played a significant role in the administration of the Spanish colonies.

Successive kings kept elected assemblies out of Spain’s empire. Royal officials were generally appointees from Spain, rather than criollos, or creoles, as persons born of European ancestry in the colonies were called. Given the vastness of the empire, local municipal councils, universities, merchant organizations, and craft guilds enjoyed considerable independence.

Colonists in Spanish America

“The maxim of the conqueror must be to settle,” said one Spanish official. The government barred non-Spaniards from emigrating to its American domains, as well as non-Christian Spaniards, including Jews and Moors. But the opportunity for social advancement drew numerous colonists from Spain—a total of 750,000 in the three centuries of Spain’s colonial rule. Some came as laborers, craftsmen, and soldiers. Others came as government officials, priests, and minor aristocrats, all ready to direct the manual work of Indians, since living without having to labor was a sign of noble status.

Although persons of European birth, called peninsulares, stood atop the social hierarchy, they never constituted more than a tiny proportion of the population of Spanish America. Native inhabitants always outnumbered European colonists. The Spanish forced tens of thousands of Indians to work in gold and silver mines, which supplied the empire’s wealth, and on large-scale farms, or haciendas, controlled by Spanish landlords. Yet large areas remained under Native control. Like the French empire and unlike the English, Spanish authorities granted Indians certain rights within colonial society.

In contrast, Spaniards seldom questioned the enslavement of Africans. From the early 1500s, the Spanish demand for enslaved labor fueled the Atlantic slave trade. The Spanish crown ordered wives of colonists to join them in America and demanded that single men marry. But with the population of Spanish women in the colonies low at first, many single Spanish men married and had children with Native women. By 1600, mestizos (persons of mixed origin) made up a large part of the urban population of Spanish America. Over time, Spanish America evolved into a hybrid culture, part Spanish, part Native, and in some areas part African, but with a single official faith, language, and governmental system (although Native languages survived). In 1531, a Nahua Indian, Juan Diego, reported seeing a vision of the Virgin Mary, speaking the Nahuatl language, near a Mexican village. The Virgin of Guadalupe would come to be revered by millions as a symbol of the mixing of Native and Spanish cultures, and later of the modern nation of Mexico.

Christianity and Conquest

What allowed one nation, the seventeenth-century Dutch legal thinker Hugo Grotius wondered, to claim possession of lands that “belonged to someone else”? This question rarely occurred to most of the Europeans who crossed the Atlantic in the wake of Columbus’s voyage, or their monarchs. Following the exclusivist mandate of Christianity, they expected the people they encountered in America to abandon their own beliefs and traditions and embrace those of the newcomers.

More information

“Young Woman with a Harpsichord,” Mexico, 1735–1750. Oil on canvas.�Depicts an upper class woman living in Mexico in the early 1700s. She wears a long, brightly colored red dress with blue detailing and a necklack with a cross on it. Holding a fan in one hand, and pointing to a harpsichord with the other, the portrait captures her whole body as she stares straight at the viewer.

Young Woman with a Harpsichord, a colorful painting from Mexico in the early 1700s, depicts an upper-class woman. Her dress, jewelry, fan, the cross around her neck, and the musical instrument all emphasize that while she lives in the colonies, she embodies the latest in European fashion and culture.

Europeans brought with them not only a long history of using violence to subdue their internal and external foes but also a missionary zeal to spread the benefits of their own civilization to others while reaping the rewards of empire. To legitimize Spain’s claim to rule the Americas, a year after Columbus’s first voyage, Pope Alexander VI divided the non-Christian world between Spain and Portugal, declaring that most of the Americas belonged to Spain and most of Africa belonged to Portugal. Of course, the people who lived in those places did not agree. The pope justified this pronouncement by requiring Spain and Portugal to spread Catholicism.

European Christians became religious rivals in the sixteenth century, when the Protestant Reformation divided the Catholic Church. In 1517, Martin Luther, a German priest, posted his Ninety-Five Theses, which accused the church of worldliness and corruption. Luther wanted to cleanse the church of abuses such as the sale of indulgences (official dispensations forgiving sins). He insisted that all believers should read the Bible for themselves, rather than relying on priests to interpret it for them. His call for reform led to the rise of new Protestant churches independent of Rome and plunged Europe into more than a century of religious and political strife.

Spain, the most powerful bastion of orthodox Catholicism, redoubled its efforts to convert Indians to the “true faith.” National glory and religious mission went hand in hand. Convinced of the superiority of Catholicism to all other religions, Spain insisted that the primary goal of colonization was to save Indians from heathenism and prevent them from falling under the sway of Protestantism. Lacking the later concept of “race” as an unchanging, inborn set of qualities and abilities, many Spanish writers insisted that Indians could in time be “brought up” to the level of European civilization. To them, this transition would require not only the destruction of Native political structures but also a transformation of their economic and spiritual lives.

Native Rights and Freedoms in the Spanish Empire

Spaniards argued over the balance between conversion and profits. The conquistadores often used brutal violence to force Native men and women to submit to them, violence that many Christians found inconsistent with the mandate to convert and “civilize” Indians.

As early as 1537, Pope Paul III, who hoped to see Indians become devout subjects of Catholic monarchs, outlawed their enslavement (an edict never extended to apply to Africans). His decree declared Indians to be “truly men,” who must not be “treated as dumb beasts.” Starting in the 1520s, the Dominican priest Bartolomé de Las Casas wrote accounts of brutal Spanish atrocities toward the Native people of the Caribbean islands. Las Casas freed his own Indian slaves and began to preach against the injustices of Spanish rule.

Las Casas narrated in shocking detail the burning alive of men, women, and children and the imposition of forced labor. The Indians, he wrote, had been “totally deprived of their freedom and were put in the harshest, fiercest, most terrible servitude and captivity.” Las Casas insisted that Spain had no grounds on which to deprive them of their lands and liberty. “The entire human race is one,” he proclaimed, and he called for Indians to enjoy “all guarantees of liberty and justice” from the moment they became subjects of Spain. “Nothing is certainly more precious in human affairs, nothing more esteemed,” he wrote, “than freedom.”

Largely because of Las Casas’s efforts, Spain in 1542 issued a proclamation that became known as the New Laws, commanding that Indians no longer be enslaved. And the government established the repartimiento system, whereby Native towns were required to provide a fixed amount of labor each year to Spanish mines or farms. As tributary towns, they were ruled by Native leaders and lived according to their own laws and customs, as long as they paid their annual tribute.

Las Casas’s writings, translated into several European languages, contributed to the spread of the Black Legend—the image of Spain as a uniquely brutal and exploitative colonizer. In reality, all empires were highly exploitative. But the Black Legend would provide a potent justification for other European powers to challenge Spain’s predominance in the Americas.

Exploring North of Mexico

The hope of finding a new kingdom of gold soon led Spanish explorers north. In 1508, Spain established the first permanent colony in what is now the United States. That first colony was on the island of Puerto Rico, now a U.S. “commonwealth.” Juan Ponce de León sent a considerable amount of Puerto Rican gold to Spain, while keeping some for himself. In 1513, he embarked for Florida, in search of wealth, slaves, and a fountain of eternal youth, only to be repelled by Calusa Indians. In 1528, another Spanish expedition landed in Florida, but the men became separated from their ships, and only four of them made it back to Mexico. For seven years, the four survivors wandered through the lands of Native peoples, from Florida to the desert of the Southwest and northern Mexico. One, Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, wrote an account of his adventures.

More information

“Spanish conquistadores murdering Indians at Cuzco, in Peru. The Dutch-born engraver Theodor de Bry and his sons illustrated ten volumes about New World exploration published between 1590 and 1618. A Protestant, de Bry created vivid images that helped to spread the Black Legend of Spain as a uniquely cruel colonizer.”

Spanish conquistadores murdering Indians at Cuzco, in Peru. The Dutch-born engraver Theodor de Bry and his sons illustrated ten volumes about the exploration of the Americas published between 1590 and 1618. A Protestant, de Bry created vivid images that helped to spread the Black Legend of Spain as a uniquely cruel colonizer.

One of the four survivors was an enslaved African named Esteban. After walking all the way to Mexico with Cabeza de Vaca in 1536, Esteban returned north, leading the expedition of Friar Marcos de Niza. Esteban went farther north than Niza, becoming the first African and first non-Indian to explore northern Mexico, Arizona, and New Mexico.

In the late 1530s and 1540s, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo explored the Pacific coast as far north as present-day Oregon, and expeditions led by Hernando de Soto, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, and others marched through the Gulf region and the Southwest, fruitlessly searching for gold. Coronado followed Esteban’s path to the interior of the continent and became the first European to encounter the immense herds of bison that roamed the Great Plains. The armies led by Coronado and de Soto spread devastation among Native communities. But they were unsuccessful in their quest for riches, and most of the men—including de Soto—did not make it out alive.

Florida and the Spanish

Spain hoped to establish a military base in present-day Florida to combat pirates who threatened the treasure fleet that each year sailed from Havana for Europe loaded with gold and silver from Mexico and Peru. Spain also wanted to forestall French incursions in the area. In 1565, Philip II of Spain authorized Pedro Menéndez de Avilés to lead a colonizing expedition to Florida. Menéndez destroyed a small outpost at Fort Caroline, which a group of Huguenots (French Protestants) had established in 1562 near present-day Jacksonville.

The Spanish did not fulfill their ambitions for Florida. After destroying the French Fort Caroline, they established forts from present-day Miami to the Chesapeake Bay. Yet by 1574, Native people had destroyed almost all of these attempts. Only St. Augustine, Florida, survived. It remains the oldest site in the continental United States continuously inhabited by European settlers and their descendants.

Having found no gold and little to attract Spanish settlers, the crown invited Franciscan missionaries to establish missions, including among the Guales north of St. Augustine in what is now Georgia, the Timucuas in central Florida, and the Apalachees in the Florida panhandle. Many Native communities were interested in the missionaries, who brought useful goods and had compelling spiritual ideas that the inclusivist nature of Indigenous religions allowed them to incorporate. Some Native leaders or communities were able to increase their power in the region by establishing permanent connections to Spanish trade. But people who lived in or near missions also found they were subjected to violence and to European diseases that wreaked havoc on the crowded communities.

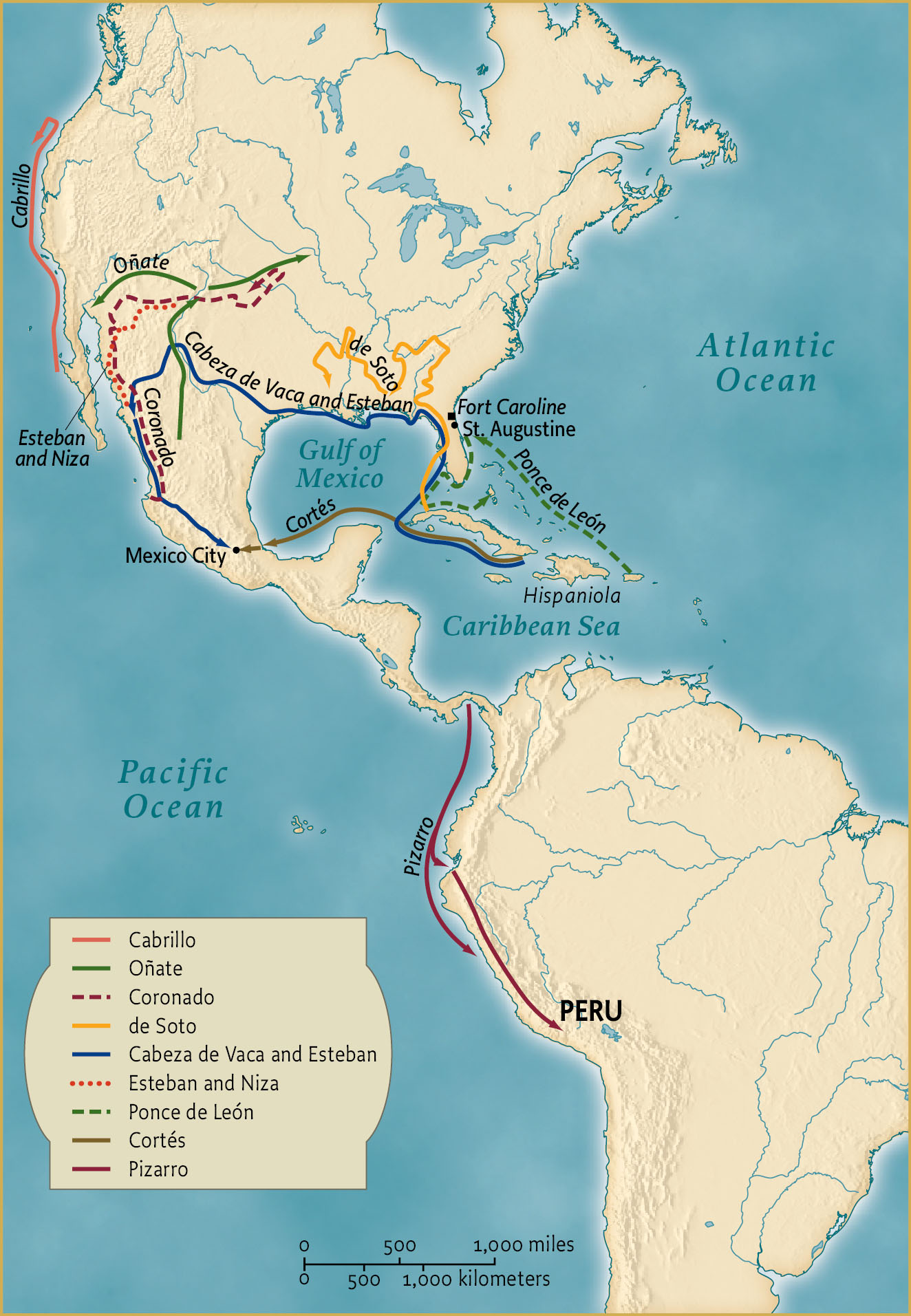

EARLY SPANISH CONQUESTS AND EXPLORATIONS IN THE AMERICAS

More information

“EARLY SPANISH CONQUESTS AND EXPLORATIONS IN THE Americas By around 1600, New Spain had become a vast empire stretching from the modern-day American Southwest through Mexico, Central America, and into the former Inca kingdom in South America. This map shows early Spanish exploration, especially in the present-day United States. Pizarro’s route leaves Panama and follows the coast of South America to Peru, and then goes inland down the center of Peru. Ponce de León’s route leaves from Hispaniola and goes along the eastern Caribbean Islands to the middle of the east coast of Florida, down around the tip of Florida, to the northern coast of Cuba, and then to the Bahamas. De Soto’s route leaves Cuba, follows the west coast of Florida, and continues up into the southern part of Georgia, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Louisiana. Cabeza de Vaca and Esteban’s route leaves Cuba, follows the Gulf coasts of Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, and moves inland through Texas and Arizona and down into Mexico. Coronado’s route leaves Mexico, travels up the west coast of Mexico, and then turns inland across Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado. Oñate’s route leaves Mexico; reaches Santa Fe, New Mexico; and splits into two routes, one headed southwest toward the Baja Peninsula and the other headed northeast toward Nebraska. Cort�s’s route leaves Cuba, reaches the coast of Mexico, and heads inland to the center of Mexico and Mexico City. Cabrillo’s route leaves the Baja Peninsula and follows the coasts of California and part of Oregon.”

By around 1600, New Spain had become a vast empire stretching from the modern-day American Southwest through Mexico and Central America and into the former Inca kingdom in South America. This map shows early Spanish exploration, especially in the present-day United States.

In some places, Indians and the Spanish reached compromises that allowed the missionaries to stay. In others, the Native people threw them out. Beginning in 1597, Guale Indians planned and launched an attack on missions in their province. One Guale explained the attacks by noting that the missionaries had sought to eliminate “our dances, banquets, feasts, celebrations, and wars. . . . They persecute our old people by calling them witches.” Guales and their allies ransacked missions and killed missionaries. In general, Florida remained a Native-dominated place. As late as 1763, Spanish Florida had only 4,000 inhabitants of European descent.

More information

St. Anthony and the Infant Jesus, painted on a tanned buffalo hide by a Franciscan priest in New Mexico in the early eighteenth century. This was not long after the Spanish reconquered the area, from which they had been driven by the Pueblo Revolt.

St. Anthony and the Infant Jesus, painted on a tanned bison hide by a Franciscan priest in New Mexico in the early eighteenth century. This was not long after the Spanish reconquered the area, from which they had been driven by the Pueblo Revolt.

The Southwest and the Spanish

Half a century after Coronado’s failed expedition, the Spanish returned to the pueblos on the Rio Grande to attempt a permanent colony called New Mexico. In 1598, Juan de Oñate led a group from Mexico of several hundred soldiers, Franciscan missionaries, and colonists.

Rather than establishing their own town and farms, Oñate and his followers demanded that Native people feed and work for them, killing and raping those who did not comply. Fighting back was difficult because the Puebloans were not one people but instead inhabited over eighty independent towns and spoke six different languages. Finally, the people of the pueblo of Acoma had enough, and they killed a Spanish patrol that included Oñate’s nephew. In the ensuing battle, Oñate’s forces killed an estimated 800 of Acoma’s men, women, and children.

In response to protests from the missionaries and Native leaders of the Pueblos, authorities in Mexico City in 1606 deposed and punished Oñate. In 1609, they ordered the New Mexican colonists to establish a separate town and grow their own food. In the future, only married soldiers were to be stationed in New Mexico to reduce the likelihood of sexual violence. Founded around 1610, the colonial town of Santa Fe would be the first permanent European settlement in the Southwest, but it remained a small settlement, surrounded by Native peoples.

The Pueblo Revolt

![]() The Pueblo Revolt

The Pueblo Revolt

Some Native people left their pueblos to build new towns farther from the Spanish. Others saw benefits in Spanish alliance, including new tools and crops and the protection of Spanish forces against their Apache and Navajo enemies. Many also found Catholicism appealing and accepted baptism, adding Jesus and the Catholic saints to their already rich spiritual pantheon. But as the Inquisition—the persecution of non-Catholics—became more intense in Spain, so did the friars’ efforts to stamp out traditional religious ceremonies. By burning Native sacred objects and threatening Native religious leaders, the missionaries alienated far more Indians than they converted. A prolonged drought that began around 1660 and Navajo and Apache attacks added to local discontent.

The Pueblo peoples came together under the inspiring leadership of a man named Popé. A religious leader born around 1630 in San Juan Pueblo, Popé was one of forty-seven Indians arrested in 1675 for practicing their traditional religion. Four of the prisoners were hanged, and the rest, including Popé, were brought to Santa Fe to be publicly whipped. After this brutal humiliation, Popé returned home and began holding secret meetings in Pueblo communities.

Under Popé’s leadership, the Puebloans joined in a coordinated uprising. Some 2,000 warriors destroyed farms and missions, killing 400 colonists, including 21 Franciscan missionaries. The Spanish had no choice but to abandon the colony. Within a few weeks, a century of colonization in the area had been destroyed. The Pueblo Indians had reestablished the freedom lost through Spanish conquest.

The Pueblo Revolt was a complete victory over the Spanish. The victors turned with a vengeance on symbols of European culture, uprooting fruit trees, destroying cattle, burning churches and images of Christ and the Virgin Mary, and wading into rivers to wash away their Catholic baptisms. They rebuilt their places of worship, called kivas, and resumed sacred dances the friars had banned. “The God of the Spaniards,” they shouted, “is dead.”

The Pueblo Revolt inspired revolts across northern Mexico. Native towns that had experienced similar troubles with the Spanish struck back in attempts to regain their independence. Apache bands took advantage of the fighting to expand their raids across the region. While the Spanish never gave up their ambitions to colonize northern Mexico, their hold on it was always tenuous.

Yet at the same time, cooperation among the Rio Grande Pueblos evaporated. By the end of the 1680s, warfare had broken out among several Pueblos, even as Apache and Navajo raids continued. Popé died around 1690. In 1692, the Spanish launched an invasion that eventually reestablished the colony of New Mexico. Some communities welcomed them back as a source of military protection. And Spain had learned a lesson. In the eighteenth century, colonial authorities adopted a more tolerant attitude toward traditional religious practices and made fewer demands on Indian labor.

VOICES OF FREEDOM

From BARTOLOMÉ DE LAS CASAS, HISTORY OF THE INDIES (1528)

Las Casas was the Dominican priest who condemned the treatment of Indians in the Spanish empire. His widely disseminated writings helped to establish the Black Legend of Spanish cruelty.

Listen as you read

The Indians [of Hispaniola] were totally deprived of their freedom and were put in the harshest, fiercest, most horrible servitude and captivity which no one who has not seen it can understand. Even beasts enjoy more freedom when they are allowed to graze in the fields. But our Spaniards gave no such opportunity to Indians and truly considered them perpetual slaves, since the Indians had not the free will to dispose of their persons but instead were disposed of according to Spanish greed and cruelty, not as men in captivity but as beasts tied to a rope to prevent free movement. When they were allowed to go home, they often found it deserted and had no other recourse than to go out into the woods to find food and to die. When they fell ill, which was very frequently because they are a delicate people unaccustomed to such work, the Spaniards did not believe them and pitilessly called them lazy dogs and kicked and beat them; and when illness was apparent they sent them home as useless. . . . They would go then, falling into the first stream and dying there in desperation; others would hold on longer but very few ever made it home. I sometimes came upon dead bodies on my way, and upon others who were gasping and moaning in their death agony, repeating “Hungry, hungry.” And this was the freedom, the good treatment and the Christianity the Indians received.

About eight years passed under [Spanish rule] and this disorder had time to grow; no one gave it a thought and the multitude of people who originally lived on the island . . . was consumed at such a rate that in these eight years 90 per cent had perished. From here this sweeping plague went to San Juan, Jamaica, Cuba and the continent, spreading destruction over the whole hemisphere.

From FRIAR MARCOS DE NIZA’S ACCOUNT OF HIS VOYAGE WITH ESTEBAN (1539)

In the 1520s and 1530s, after the conquest of Mexico City, Spanish conquistadores raided Native lands to the north for captives to sell as slaves. In part due to Bartolomé de Las Casas, the Spanish monarchs outlawed Indian slavery in their empire. In 1539, Friar Marcos de Niza traveled north from Mexico City to spread the news that the slave raids would stop and priests would come instead. His guide was Esteban, an African man who had been enslaved by the Spanish. Esteban had journeyed from Florida through Texas to northern Mexico with the man who owned him under Spanish law, Andrés Dorantes, as well as Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca. Still technically enslaved to Dorantes, Esteban now set off to lead Niza through northern Mexico to Arizona and New Mexico. Niza begins his account by explaining that two different Native groups will accompany him, Esteban, and another priest, Father Onoratto. The first are northern Indians, whom the Spanish had previously captured in the north and held in bondage near Mexico City. The Viceroy of Mexico has freed them to return home. The second group is Opatas of northwestern Mexico who came to offer to accompany Niza and Esteban as they returned the formerly enslaved people to their homes.

Listen as you read

I took with me, as my colleague, Father Onoratto, and Dorantes’ Negro Esteban and certain Indians whom the lord Viceroy freed and bought for this purpose and whom the governor of New Galicia, Francisco Vasques de Coronado turned over to me, as well as many Indians [who] came to the valley of Culiacán expressing great joy, because the freed Indians assured them that the governor sent us ahead to let them know about their freedom and that people would not be enslaving them or making war on them or mistreating them, and that this was the wish and the order of his Majesty.

With this company I made my journey . . . and on the way I found much welcome and many offerings of things to eat . . . and they made houses of straw mats and branches for me along the way where no people were living. I stayed in Petatlan for three days because my colleague Father Onoratto had fallen ill. I had to leave him there and, as I had been instructed, continue my journey, led by the Holy Spirit through no merit of my own and accompanied by the above-mentioned Esteban, Dorantes’ Negro, and some of the freed Indians and many people of the region, who received me with welcome and rejoicing and triumphal arches and who gave me of their food, which wasn’t much, because, they said, they had had no rain for three years and because the Indians of that region were more intent on hiding than on sowing, for fear of the Christians, who up until then had been making war on them and enslaving them. . . .

Glossary

- creoles

- Persons born in the Americas of European ancestry.

- hacienda

- Large-scale farm in the Spanish empire worked by Native American laborers.

- mestizos

- Spanish word for persons of mixed Native American and European ancestry.

- Ninety-Five Theses

- The list of moral grievances against the Catholic Church by Martin Luther, a German priest, in 1517.

- Las Casas, Bartolomé de

- A Catholic missionary who renounced the Spanish practice of coercively converting Indians and advocated their better treatment. In 1552, he wrote A Brief Relation of the Destruction of the Indies, which described the cruel treatment of the Indians by the Spanish.

- repartimiento system

- Spanish labor system under which Indians were legally free and able to earn wages but were also required to perform a fixed amount of labor yearly; replaced the encomienda system.

- Black Legend

- Idea that the Spanish empire was more oppressive toward Indians than other European empires; used as a justification for English imperial expansion.

- Pueblo Revolt

- Uprising in 1680 by allied Pueblo led by Popé that temporarily drove Spanish colonists out of New Mexico.

- Indians [of Hispaniola]

- The author is referring to the Indigenous peoples of the island of Hispaniola. Hispaniola or “little Spain” was the name given to the island that encompasses present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic. The island was divided in the late seventeenth century following conflicts between the French and Spanish.

- such work

- The Taìno enjoyed a complex and thriving community before the arrival of the Spaniards. However, the Spaniards forced the Taìno to work in gold mines, preventing them from planting the crops that they relied on for generations. The grueling forced labor, coupled with the diseases such as smallpox that the Spanish brought with them, drastically cut their populations by as much as 90 percent.

- this sweeping plague

- Here Las Casas is referring to Spanish rule and the mistreatment of Native peoples throughout the region as Spain gained control of more islands in the Caribbean.

- Negro Esteban

- Although he had recently completed a long journey after surviving a shipwreck off the coast of present-day Florida, Esteban, a man of African (Moorish) descent, led the expedition, despite still being enslaved by another member of the expedition, Andrés Dorantes.

- the lord Viceroy

- Don Antonio de Mendoza served as the viceroy, or governor, of New Spain. It was Mendoza who organized De Niza’s voyage northward seeking riches and reassuring the Native peoples that they would no longer be kidnapped and sold into slavery.

- more intent on hiding than on sowing

- It was this treatment that Las Casas described in his History of the Indies (1528) that resulted in the starvation of countless Native peoples.