What were the chief features of the French and Dutch empires in North America?

THE FRENCH AND DUTCH EMPIRES

If the Black Legend inspired a sense of superiority among Spain’s European rivals, the precious metals that poured from the Americas into the Spanish treasury aroused the desire to try to match Spain’s success. The establishment of Spain’s American empire transformed the world economy. The Atlantic replaced the overland route to Asia as the major axis of global trade. During the seventeenth century, the French, Dutch, and English established colonies in North America. England’s mainland colonies, to be discussed in the next chapter, consisted of agricultural settlements with growing populations whose hunger for land produced incessant conflict with Native peoples. New France and New Netherland were primarily commercial ventures that, like Spanish Florida and New Mexico, never attracted large numbers of colonists. Because French and Dutch settlements were more dependent than the English on Indians as trading partners and military allies, Native Americans exercised more power and enjoyed more freedom in their relations with these settlements.

French Colonization

The French initially aimed to find gold and to locate a Northwest Passage—a sea route connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific. But early French explorers were soon disappointed. For most of the sixteenth century, only explorers, fishermen, pirates preying on Spanish shipping farther south, and, as time went on, fur traders visited the eastern coast of North America. French efforts to establish settlements in Newfoundland and Nova Scotia failed, beset by Native resistance and inadequate planning and financing. Not until the seventeenth century would France, as well as England and the Netherlands, establish permanent settlements in North America.

The explorer Samuel de Champlain, sponsored by a French fur-trading company, founded Quebec in 1608. In 1673, the Jesuit priest Jacques Marquette and the fur trader Louis Joliet located the Mississippi River, and by 1681 René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, had descended to the Gulf of Mexico, claiming the entire Mississippi River valley for France. On European maps, New France eventually formed a giant arc along the St. Lawrence and Mississippi rivers. But the colonial population would remain small and dependent on Native alliances.

By 1700, the number of white inhabitants of New France had risen to only 19,000. With a far larger population than England, France sent many fewer emigrants to the Western Hemisphere. The government at home feared that significant emigration would undermine France’s role as a European great power and might compromise its effort to establish trade and good relations with Native Americans. Unfavorable reports about America circulated widely in France. Canada was widely depicted as an icebox, a land of “savage” Indians, a dumping ground for criminals. Most French who left their homes during these years preferred to settle in the Netherlands, Spain, or the West Indies. The revocation in 1685 of the Edict of Nantes, which had extended religious toleration to French Protestants, led well over 100,000 Huguenots to flee their country. But they were not welcome in New France, which the crown desired to remain an outpost of Catholicism.

The Fur Trade

The viability of New France, with its small white population and emphasis on the fur trade, depended on friendly relations with Native nations. The French and their Native allies worked out a complex series of military, commercial, and diplomatic connections. The Jesuits, a missionary religious order, did seek, with some success, to convert Indians to Catholicism. Unlike Spanish missionaries in early New Mexico, they allowed Christian Indians to retain a high degree of independence and much of their traditional social structure, and they did not seek to suppress all traditional religious practices. Indians who converted to Catholicism were promised full membership in French colonial society. In fact, however, it was far rarer for Natives to adopt French ways than for French settlers to become attracted to the “free” life of the Indians.

More information

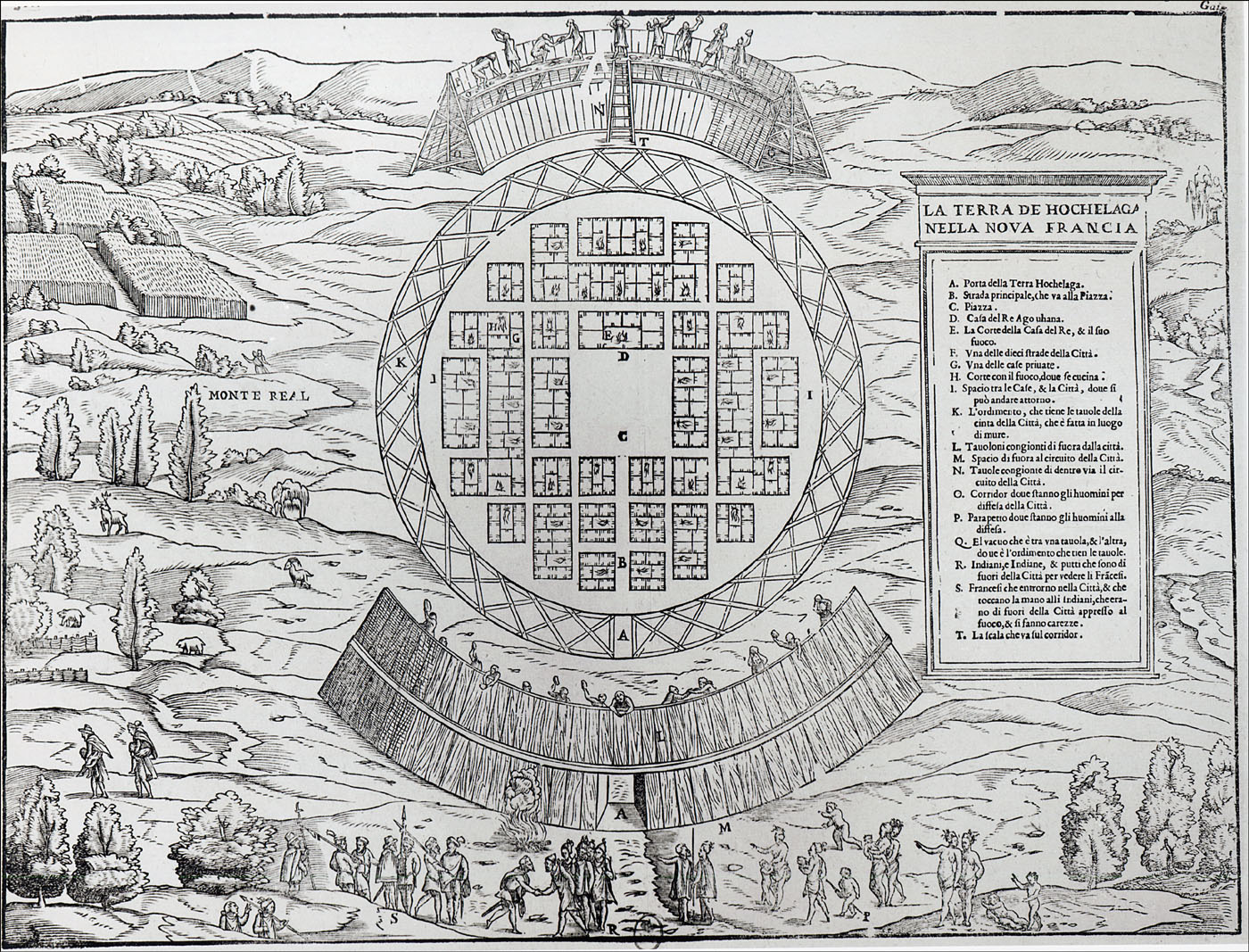

An engraving of the Huron town Hochelaga. The black and white image features a large circle in the center, which containes several rectangles. Around the circle is a rounded wooden wall with people standing behind it. They eppear to be throwing rocks at the people below. Towards the top of the image is another rounded wall facing the opposite direction. The back of the wall is visible, revealing a platform on which the people stand and the ladder that they used. To the left and right of the circle are hills and trees, with some animals roaming about. At the very foreground of the image are more people, presumably the targets of the rocks that are being thrown. They appear to be a mixture of men and women, indigenous people and soldiers. There are naked women holding children to the right and men holding shields and spears and wearing helmets to the left.On the right-hand side of the image is a key written in French.

An engraving of the Wendat town Hochelaga, site of modern-day Montreal, from a book about exploration by Giovanni Battista Ramusio, an Italian geographer, published in 1556.

Native Americans required French traders to follow their rules. The first French trading partners along the St. Lawrence River were Innus (Montagnais), Algonquins, and Wendats (Hurons), who recruited French trade and demanded good prices for furs. (The Algonquins were a nation within the large linguistic grouping known as Algonquian.) When the French established Quebec, it was on Algonquin land and because Algonquin leaders invited them. As Champlain recognized, “my enterprises and discoveries . . . seem to be possible only through their means.” These allies of the French also insisted that the French join their military alliance against their enemy: the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) League, discussed previously.

It is no surprise that Native Americans wanted European trade. They incorporated European goods into their existing ways of life, using copper kettles as well as ceramic pots and wielding guns for some tasks and bows and arrows for others. Some Native women married the single French men who came to New France and incorporated them and their children into Native communities.

In this engraving, which appears in Samuel de Champlain’s 1613 account of his voyages, Champlain, wearing European armor and brandishing an arquebus (an advanced weapon of the period), stands at the center of this 1609 pitched battle between his Algonquin, Innu, and Wendat allies and their Mohawk enemies.

The Dutch Empire

In 1609, Henry Hudson, an Englishman employed by the Dutch East India Company, sailed into New York Harbor searching for a Northwest Passage to Asia. Hudson and his crew became the first Europeans to sail up the river that now bears his name. Hudson did not find a route to Asia, but he did encounter Lenapes, Munsees, and Mahicans more than willing to trade furs for European goods. He claimed the area for the Netherlands, and his voyage planted the seeds for what would eventually become a great metropolis, New York City. When the powerful Mohawks of the Haudenosaunee League learned about the Dutch, they and their Mahican allies persuaded them that the most lucrative fur trade would be on the Hudson River near present-day Albany. By 1614, Dutch traders had established an outpost there at Fort Orange. Ten years later, the Dutch West India Company, which had been awarded a monopoly of Dutch trade with America, settled colonists on Manhattan Island.

These ventures formed one small part of the rise of the Dutch overseas empire. In the early seventeenth century, the Netherlands dominated international commerce, and Amsterdam was Europe’s foremost shipping and banking center. The Dutch invented the joint stock company, a way of pooling financial resources and sharing the risk of maritime voyages, which proved central to the development of modern capitalism. With a population of only 2 million, the Netherlands established a far-flung empire that reached from Indonesia to South Africa and the Caribbean and temporarily wrested control of Brazil from Portugal.

Dutch Freedom

The Dutch prided themselves on their devotion to liberty. Indeed, in the early seventeenth century they enjoyed two freedoms not recognized elsewhere in Europe—freedom of the press and of private religious practice. Amsterdam became a haven for persecuted Protestants from all over Europe, including French Huguenots, German Calvinists, and those, like the Pilgrims, who desired to separate from the Church of England. Jews, especially those fleeing from Spain, also found refuge there. During the seventeenth century, the nation attracted about half a million migrants from elsewhere in Europe. Many of these newcomers helped to populate the Dutch overseas empire.

Freedom in New Netherland

Despite the Dutch reputation for cherishing freedom, New Netherland was hardly governed democratically. New Amsterdam, the main population center, was essentially a fortified military outpost controlled by appointees of the Dutch West India Company. Neither an elected assembly nor a town council, the basic unit of government at home, was established. In other ways, however, the colonists enjoyed more liberty, especially in religious matters, than their counterparts elsewhere in North America.

Dutch women enjoyed far more independence than in other colonies. Unlike in England and its colonies, under Dutch law, married women retained their separate legal identity. They could go to court, borrow money, and own property. Men’s wills generally left their possessions to their widows and daughters as well as sons. Margaret Hardenbroeck, the widow of a New Amsterdam merchant, expanded her husband’s business and became one of the town’s richest residents after his death in 1661.

Enslaved men and women in New Netherland were able to establish some rights for themselves as well. The Dutch dominated the Atlantic slave trade in the early seventeenth century, and they introduced slaves into New Netherland. But in the 1640s a petition by a group of enslaved Africans persuaded the Dutch West India Company to institute a system of “half-freedom”—that is, they were required to pay an annual fee to the company and work for it when called upon, but they were given land to support their families. Enslaved people worked on family farms or for household or craft labor, not on large plantations as in the West Indies.

The Dutch and Religious Toleration

New Netherland attracted a remarkably diverse population. As early as the 1630s, at least eighteen languages were said to be spoken in New Amsterdam, whose residents included not only Dutch settlers but also Africans, Belgians, English, French, Germans, Irish, and Scandinavians.

More information

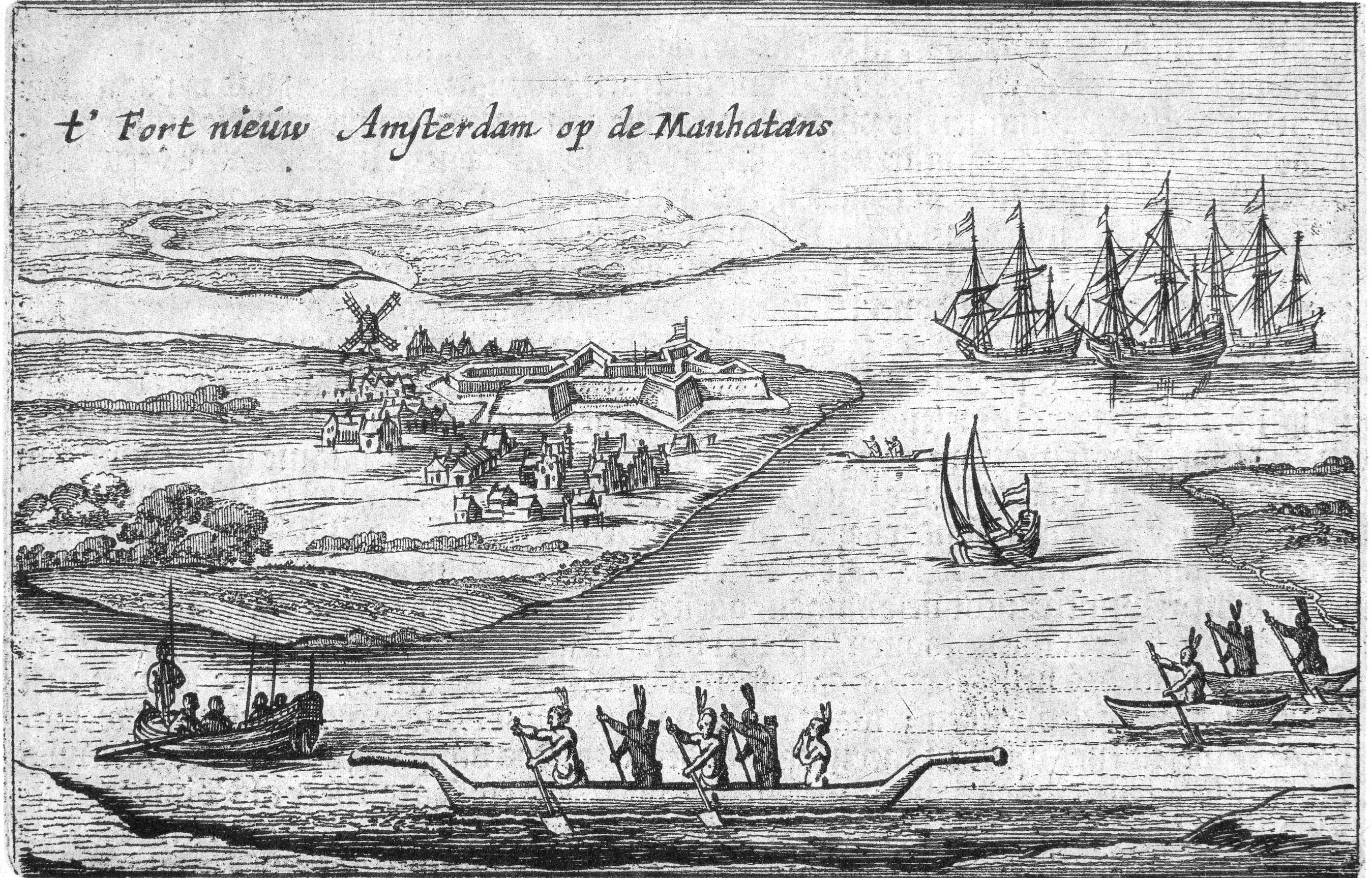

A detail of the earliest known engraving of New Amsterdam depicts Dutch and Indian boats in the harbor. In the foreground, five Native Americans row a canoe. They row in an organized fashion, with two paddling on the left side of the boat, two paddling on the right side, and one in the back calling out directions. They are depicted wearing feathers on their heads. Behind them are three more Native Americans in canoes and one rowboat holding five Dutch settlers. In the midground is the island of Manhattan. There is a large fortress on the coast, surrounded by several buildings and structures. There is still a lot of open space and trees on the island. Off the coast is another Native American canoe and a Dutch sailboat. In the distance, there is another land mass with a river that empties into the harbour. There are also three large Dutch ships with high masts, anchored farther off the coast.

Coastal Native Americans were adept mariners. This detail from the earliest known engraving of New Amsterdam (1627) depicts Dutch and Lenape Indian boats in the harbor.

Though Dutch settlers adhered to a wide variety of religions, it would be wrong to attribute modern ideas of religious freedom to either the Dutch government and company at home or the rulers of New Netherland. Both Holland and New Netherland had an official religion, the Dutch Reformed Church, one of the Protestant national churches to emerge from the Reformation. The Dutch commitment to freedom of conscience extended to religious devotion exercised in private, not public worship in nonestablished churches.

When Jews, Quakers, Lutherans, and others demanded the right to practice their religion openly, Governor Petrus Stuyvesant adamantly refused, seeing such diversity as a threat to a godly, prosperous order. Under Stuyvesant, the colony was more restrictive in its religious policies than the Dutch government at home. When twenty-three Jews arrived in New Amsterdam in 1654 from Brazil and the Caribbean, Stuyvesant ordered them to leave. But the company overruled him, noting that Jews at home had invested “a large amount of capital” in its shares.

As a result of Stuyvesant’s policies, challenges arose to the limits on religious toleration. One, known as the Flushing Remonstrance, was a 1657 petition by a group of English settlers protesting the governor’s order barring Quakers from living in the town of Flushing, on Long Island. Stuyvesant ordered several signers arrested for defying his authority.

Nonetheless, it is true that the Dutch dealt with religious pluralism in ways quite different from the practices common in other European empires. Religious dissent was tolerated—often grudgingly—as long as it did not involve open and public worship. No one in New Netherland was forced to attend the official church, nor was anyone executed for holding the wrong religious beliefs (as would happen in Puritan New England).

New Netherland and the Haudenosaunee

The Dutch came to North America to trade, and they prided themselves on getting along well with Native peoples. Mindful of the Black Legend of Spanish cruelty, the Dutch determined to treat the Native inhabitants more humanely. Having won their own independence from Spain after the longest and bloodiest war of sixteenth-century Europe, many Dutch identified with American Indians as fellow victims of Spanish oppression. From the beginning, Dutch authorities recognized Native sovereignty over the land and forbade settlement in any area unless it had been purchased.

NEW FRANCE AND NEW NETHERLAND, ca. 1650

On European maps, New France and New Netherland were large land claims, but in reality they were a few trading posts and small settlements surrounded by Native nations.

By the 1640s, Dutch traders were exporting tens of thousands of furs each year, most of them traded from the Mohawks, one of the five nations of the Haudenosaunee League. The Mohawks dominated trade at Fort Orange (later Albany). They used their market power in furs to set prices.

Some of the furs that the Mohawks sold were stolen from their enemies, seized from canoes descending the St. Lawrence River to the French posts of Montreal and Quebec. In the early decades of the 1600s, the Haudenosaunee expanded their domain far beyond their homelands, driving off or forcibly incorporating Native nations from the St. Lawrence River to the Carolinas and from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes. Although European maps labeled vast regions as New France, New Netherland, and New England, everyone knew that the Haudenosaunee were the most powerful people in the Northeast.

More information

The seal of New Netherland, adopted by the Dutch West India Company in 1630, suggests the centrality of the fur trade to the colony’s prospects. Surrounding the beaver is wampum, a string of beads used by Indians in religious rituals and as currency.

The seal of New Netherland, adopted by the Dutch West India Company in 1630, suggests the centrality of the fur trade to the colony’s prospects. Surrounding the beaver is wampum, a string of beads used by northeastern Native peoples in religious rituals and as currency.

A Trading Colony

The Dutch were good allies to the Mohawks because they had to be, but where they attempted settlements rather than trade, they created conflict with Native neighbors. In an attempt to attract settlers to North America, the Dutch West India Company promised colonists cheap livestock and free land after six years of labor. Eventually, it even surrendered its monopoly of the fur trade, opening this profitable commerce to all. The Dutch desire to attract colonists put New Amsterdam and its surrounding farms in conflict with Delawares (Lenapes and Munsees). The Dutch took more land than the Delawares had agreed to, and Dutch pigs and cattle damaged Delaware women’s crops. Delawares in turn killed and ate the invasive livestock. New Netherland Governor Willem Kieft in 1639 demanded that Delawares start paying yearly tribute in corn. A group of Delawares noted that Kieft “must be a very mean fellow to come to live in this country without being invited by them, and now wish to compel them to give him their corn for nothing.” A three-year conflict known as Kieft’s War followed that resulted in the death of an estimated 1,000 Delawares and their allies and more than 200 colonists. Many Dutch settlers fled the colony, and the war dissuaded new settlers. By the mid-1660s, the European population of New Netherland numbered only 9,000. The colony remained a tiny backwater in the Dutch empire.

Borderlands and Empire in Early America

A borderland, according to one historian, is “a meeting place of peoples where geographical and cultural borders are not clearly defined.” Numerous such places came into existence during the era of European conquest and settlement, including the contested region bordered by New Netherland, the Haudenosaunee League, New France, and France’s Algonquian and Wendat allies. In a few areas, Europeans consolidated their control, and the power of nearby Native peoples weakened. But at the edges of empire, power was always unstable, and overlapping cultural interactions at the local level defied any single pattern. And beyond those edges, across most of North America, Native nations still held all of the power. The Spanish, French, Dutch, and English empires fought one another for dominance in various parts of the continent. Despite laws restricting commerce between empires, traders challenged boundaries, traversing lands claimed by both Europeans and Indians.

Despite their differences, European empires shared certain features. All brought Christianity, new forms of technology, new legal systems and family relations, and new forms of economic enterprise and wealth creation. They also brought savage warfare and disease. These empires studied and borrowed from one another, each lauding itself as superior to the others. From the outset, dreams of freedom—for Native peoples, for settlers, for the entire world through the spread of Christianity—inspired and justified colonization. And Native peoples acted on their own dreams of freedom to fight colonialism in some times and places and, in others, to forge economic and diplomatic relationships with Europeans that they hoped would advance their own people’s sovereignty and prosperity.

Glossary

- borderland

- A place between or near recognized borders where no group of people has complete political control or cultural dominance.