![]() Eighteenth-Century Religious Freedom

Eighteenth-Century Religious Freedom

THE GROWTH OF COLONIAL AMERICA

The Salem witch trials took place precisely two centuries after Columbus’s initial voyage. In North America, three very different empires had arisen, competing for wealth and power. The urban-based Spanish empire, with a settler elite and growing mestizo population directing a large Native labor force, still relied for wealth primarily on the gold and silver mines of Mexico and South America. The French empire centered on Saint Domingue, Martinique, and Guadeloupe, plantation islands of the West Indies. On the mainland, it consisted of a thinly settled string of farms and trading posts in the St. Lawrence Valley. In North America north of the Rio Grande, the English claimed less land than their rivals but outpaced them in population.

As stability returned after the crises of the late seventeenth century, English North America experienced an era of remarkable growth. Between 1700 and 1770, crude backwoods settlements became bustling provincial capitals. The hazards of starvation and disease among colonists diminished, agricultural settlement pressed westward, and hundreds of thousands of newcomers arrived from Europe. Thanks to a high birthrate and continuing immigration, the population of England’s mainland colonies, 265,000 in 1700, grew nearly tenfold, to over 2.3 million seventy years later. At the same time, in places where Europeans brought war, enslavement, and destruction of natural resources, Native populations declined, directly because of Europeans or indirectly from their diseases. When Native people had time to recover from diseases, the effects were manageable, but when disease was accompanied by intensive colonization, the effects were catastrophic. In 1700, Native Americans still outnumbered Europeans in North America, but over the course of the next century, the population of English colonies would outstrip everyone else.

A Diverse Population

Probably the most striking characteristic of eighteenth-century British colonial society was its diversity. In 1700, the colonies were essentially English outposts. Relatively few Africans had yet been brought to the mainland, and the overwhelming majority of the white population—close to 90 percent—was of English origin. In the eighteenth century, African and non-English European arrivals skyrocketed, while the number emigrating from England declined.

|

TABLE 3.1 Origins of Free and Unfree Newcomers to British North American Colonies, 1700–1775 |

|||||

|

Total |

Slaves |

Indentured Servants |

Convicts |

Free |

|

|

Africa |

278,400 |

278,400 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Ireland |

108,600 |

— |

39,000 |

17,500 |

52,100 |

|

Germany |

84,500 |

— |

30,000 |

— |

54,500 |

|

England/Wales |

73,100 |

— |

27,200 |

32,500 |

13,400 |

|

Scotland |

35,300 |

— |

7,400 |

2,200 |

25,700 |

|

Other |

5,900 |

— |

— |

— |

5,900 |

|

TOTAL |

585,800 |

278,400 |

103,600 |

52,200 |

151,600 |

As economic conditions in England improved, the government began to rethink the policy of encouraging emigration. No longer concerned with an excess population of vagabonds and “masterless men,” authorities began to worry that large-scale emigration was draining labor from the mother country. About 40 percent of European immigrants to the colonies during the eighteenth century continued to arrive as bound laborers who had temporarily sacrificed their freedom to make the voyage to the Americas. But as the colonial economy prospered, poor indentured migrants were increasingly joined by professionals and skilled craftsmen—teachers, ministers, weavers, carpenters—whom England could ill afford to lose. This brought to an end official efforts to promote English emigration.

Attracting Settlers

Yet while worrying about losing desirable members of its population, the government in London remained convinced that colonial development enhanced the nation’s power and wealth. To bolster the Chesapeake labor force, nearly 50,000 convicts (a group not desired in Britain) were sent to work in the tobacco fields. Officials also actively encouraged Protestant immigration from the non-English (and less prosperous) parts of the British Isles and from the European continent, promising newcomers easy access to land and the right to worship freely. A law of 1740 even offered European immigrants British citizenship after seven years of residence, something that in England could be obtained only by a special act of Parliament. The widely publicized image of America as an asylum for those “whom bigots chase from foreign lands,” in the words of a 1735 poem, was in many ways a by-product of Britain’s efforts to attract settlers from non-English areas to its colonies.

Among eighteenth-century migrants from the British Isles, the 80,000 English newcomers (a majority of them convicted criminals) were considerably outnumbered by 145,000 from Scotland and Ulster, the northern part of Ireland, where many Scots had settled as part of England’s effort to subdue the island. Scottish and Scots-Irish immigrants had a profound impact on colonial society. Mostly Presbyterians, they added significantly to religious diversity in North America. Their numbers included not only poor farmers seeking land but also numerous merchants, teachers, and professionals (indeed, a large majority of the physicians in eighteenth-century America were of Scottish origin).

The German Migration

![]() Religious Freedom for German Immigrants

Religious Freedom for German Immigrants

Germans, 110,000 in all, formed the largest group of newcomers from the European continent. Most came from the valley of the Rhine River, which stretches through present-day Germany into Switzerland. In the eighteenth century, Germany was divided into numerous small states, each with a ruling prince who determined the official religion. Those who found themselves worshiping the “wrong” religion—Lutherans in Catholic areas, Catholics in Lutheran areas, and everywhere, followers of small Protestant sects such as Mennonites, Moravians, and Dunkers—faced persecution. Many decided to emigrate. Other migrants were motivated by persistent agricultural crises and the difficulty of acquiring land. Indeed, the emigration to America represented only a small part of a massive reshuffling of the German population within Europe. Millions of Germans left their homes during the eighteenth century, most of them migrating eastward to Austria-Hungary and the Russian empire, which made land available to newcomers.

DIVERSITY IN THE EUROPEAN SETTLEMENTS, ATLANTIC COAST OF NORTH AMERICA, 1760

Wherever they moved, Germans tended to travel in entire families. English and Dutch merchants created a well-organized system whereby redemptioners (as indentured families were called) received passage in exchange for a promise to work off their debt in America. Most settled in frontier areas—rural New York, western Pennsylvania, and the southern backcountry—where they formed tightly knit farming communities in which German for many years remained the dominant language. Their arrival greatly enhanced the ethnic and religious diversity of Britain’s colonies.

Religious Diversity

![]() Origin of Religious Freedom

Origin of Religious Freedom

Eighteenth-century British America was not a “melting pot” of cultures. Ethnic groups tended to live and worship in relatively homogeneous communities. But outside of New England, which received few immigrants and retained its overwhelmingly English ethnic character, American society had a far more diverse population than Britain. Nowhere was this more evident than in the practice of religion. In 1700, nearly all the churches in the colonies were either Congregational (in New England) or Anglican. In the eighteenth century, the Anglican presence expanded considerably. But the number of Dissenting congregations also multiplied.

Apart from New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania, the colonies did not adhere to a modern separation of church and state. Nearly every colony levied taxes to pay the salaries of ministers of an established church, and most barred Catholics and Jews from voting and holding public office. But increasingly, de facto toleration among Protestant denominations flourished, fueled by the establishment of new churches by immigrants, as well as new Baptist, Methodist, and other congregations created as a result of the Great Awakening, a religious revival that will be discussed in Chapter 4. By the mid-eighteenth century, Dissenting Protestants in most colonies had gained the right to worship as they pleased and own their churches, although many places still barred them from holding public office and taxed them to support the official church. Although few in number (perhaps 2,000 at their peak in eighteenth-century America), Jews also contributed to the religious diversity. German Jews, in particular, were attracted by the chance to escape the rigid religious restrictions of German-speaking parts of Europe; many immigrated to London and some, from there, to Charleston and Philadelphia. A visitor to Pennsylvania in 1750 described the colony’s religious diversity: “We find there Lutherans, Reformed, Catholics, Quakers, Menonists or Anabaptists, Herrnhuters or Moravian Brethren, Pietists, Seventh Day Baptists, Dunkers, Presbyterians, . . . Jews, Mohammedans, Pagans.”

WHO IS AN AMERICAN?

From BENJAMIN FRANKLIN, OBSERVATIONS CONCERNING THE INCREASE OF MANKIND (1751)

![]() Who Is an American?: Benjamin Franklin

Who Is an American?: Benjamin Franklin

Only a minority of immigrants from Europe to British North America in the eighteenth century came from the British Isles. Some prominent colonists found the growing diversity of the population quite disturbing. Benjamin Franklin was particularly troubled by the large influx of newcomers from Germany into Pennsylvania in the mid-eighteenth century.

Why should the Palatine [German] boors be suffered to swarm into our settlements, and by herding together establish their language and manners to the exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our language or customs, any more than they can acquire our complexion?

Which leads me to add one remark: That the number of purely white people in the world is proportionably very small. All Africa is black or tawny. Asia chiefly tawny. America (exclusive of the newcomers) wholly so. And in Europe, the Spaniards, Italians, French, Russians and Swedes, are generally of what we call a swarthy complexion; as are the Germans also, the Saxons only excepted, who with the English, make the principal body of white people on the face of the earth. I could wish their numbers were increased. And while we are, as I may call it, scouring our planet, by clearing America of woods, and so making this side of our globe reflect a brighter light to the eyes of inhabitants in Mars or Venus, why should we . . . darken its people? Why increase the sons of Africa, by planting them in America, where we have so fair an opportunity, by excluding all Blacks and Tawneys, of increasing the lovely White and Red? But perhaps I am partial to the complexion of my country, for such kind of partiality is natural to mankind.

QUESTIONS

- What is Franklin’s objection to the growing German presence?

- What does Franklin’s characterization of the complexions of various groups suggest about the reliability of his perceptions of non-English peoples?

“Liberty of conscience,” wrote a German newcomer in 1739, was the “chief virtue” of British North America, “and on this score I do not repent my immigration.” Equally important to eighteenth-century immigrants, however, were other elements of freedom, especially the availability of land, the lack of a military draft, and the absence of restraints on economic opportunity common in Europe. Skilled workers were in great demand. “They earn what they want,” one immigrant wrote to his brother in Switzerland in 1733. Letters home by immigrants spoke of low taxes, the right to enter trades and professions without paying exorbitant fees, and freedom of movement. “In this country,” one wrote, “there are abundant liberties in just about all matters.”

Native-Colonial Relations

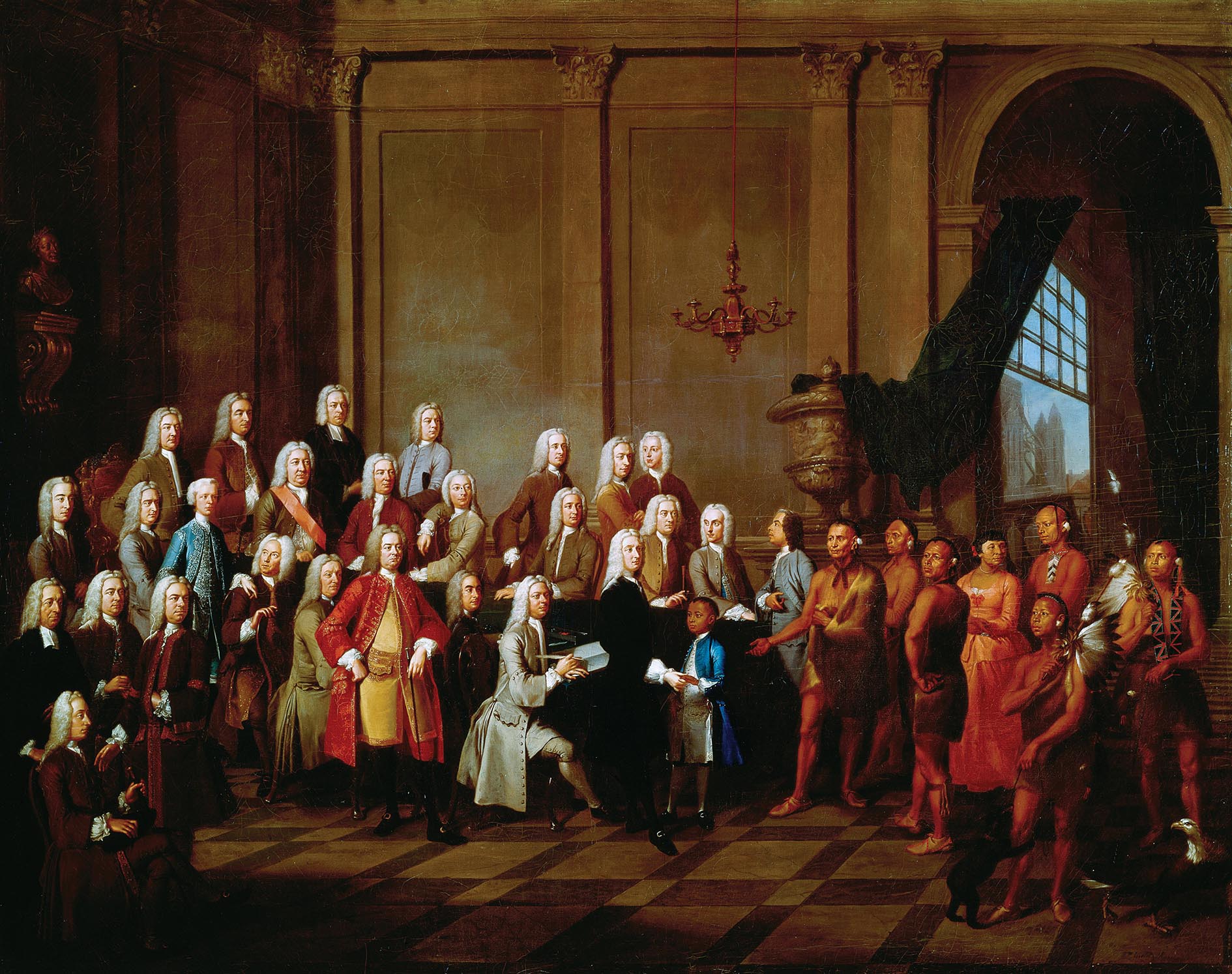

![]() Native-Colonial Relations in the Early to Mid-Eighteenth Century

Native-Colonial Relations in the Early to Mid-Eighteenth Century

The tide of newcomers, who equated liberty with possession of land, threatened to engulf Native nations on the Atlantic coast. By the eighteenth century, Native people were well integrated into global trade networks, and those who lived near colonial populations had established direct economic and diplomatic connections with Europeans. New confederacies, including the Catawbas of South Carolina and the Muscogee (Creek) Confederacy to the west of South Carolina and Georgia, united formerly independent towns and also absorbed Indigenous refugees from colonial wars. Few Indians chose to live among whites rather than in their own communities, even if preserving their independence from colonists required moving their towns farther away and becoming more interdependent with selected other Native peoples. In the 1690s, for example, Shawnees fleeing Haudenosaunee and Chickasaw raids in the Ohio Valley accepted an invitation by Delaware Indians to move onto their lands along the Delaware and Susquehanna rivers. In the 1720s and 1730s, when English, German, and Scots-Irish immigrants flooded into Pennsylvania onto those same lands, Shawnees and Delawares gradually moved upriver to preserve their independence from both the Pennsylvanians and the Haudenosaunee, who claimed them as their subordinate allies. Eventually, the Shawnees moved back to their old Ohio Valley homeland, inviting the Delawares to join them.

Like many other Native peoples in the eighteenth century, the Delawares had built strong economic and diplomatic relationships with colonies, only to be undermined by the large numbers of immigrants pushing west. While European traders saw potential profits in Native towns, nations, and confederacies, and British officials saw allies against France and Spain, farmers and planters viewed Indians as little more than an obstacle to their desire for land. The infamous Walking Purchase of 1737 brought the fraudulent dealing so common in other colonies to Pennsylvania. Colonists pressured Delawares into agreeing to an arrangement to cede a tract of land bounded by the distance a man could walk in thirty-six hours. To their amazement, Governor James Logan hired a team of swift runners, who marked out an area far in excess of what the Indians had anticipated.

By 1760, when Pennsylvania’s population, a mere 20,000 in 1700, had grown to 220,000, Native-colonist relations, initially the most harmonious in British North America, had become poisoned by suspicion and hostility. One group of Susquehannas declared “that the white people had abused them and taken their lands from them, and therefore they had no reason to think that they were now concerned for their happiness.” They pointedly reminded Pennsylvanians that “old William Penn” treated them with fairness and respect.

Regional Diversity

By the mid-eighteenth century, the different regions of the British colonies had developed distinct economic and social orders. Small farms tilled by family labor and geared primarily to production for local consumption predominated in New England and the new settlements of the backcountry (the area stretching from central Pennsylvania southward through the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and into upland North and South Carolina). The backcountry was the most rapidly growing region in North America. In 1730, the only white residents in what was then Indian country were the occasional hunter and trader. By the eve of the American Revolution, the region contained one-quarter of Virginia’s population and half of South Carolina’s. Most were farm families raising grain and livestock, but slaveowning planters, seeking fertile soil for tobacco farming, also entered the area.

In the older portions of the Middle Colonies of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, farmers were more oriented to commerce than on the frontier, growing grain both for their own use and for sale abroad and supplementing the work of family members by employing wage laborers, tenants, and in some instances slaves. Because large landlords had engrossed so much desirable land, New York’s growth lagged behind that of neighboring colonies. “What man will be such a fool as to become a base tenant,” wondered Richard Coote, New York’s governor at the beginning of the eighteenth century, “when by crossing the Hudson river that man can for a song purchase a good freehold?” With its fertile soil, favorable climate, initially peaceful Indian relations, generous governmental land distribution policy, and rivers that facilitated long-distance trading, Pennsylvania came to be known as “the best poor man’s country.” Ordinary colonists there enjoyed a standard of living unimaginable in Europe.

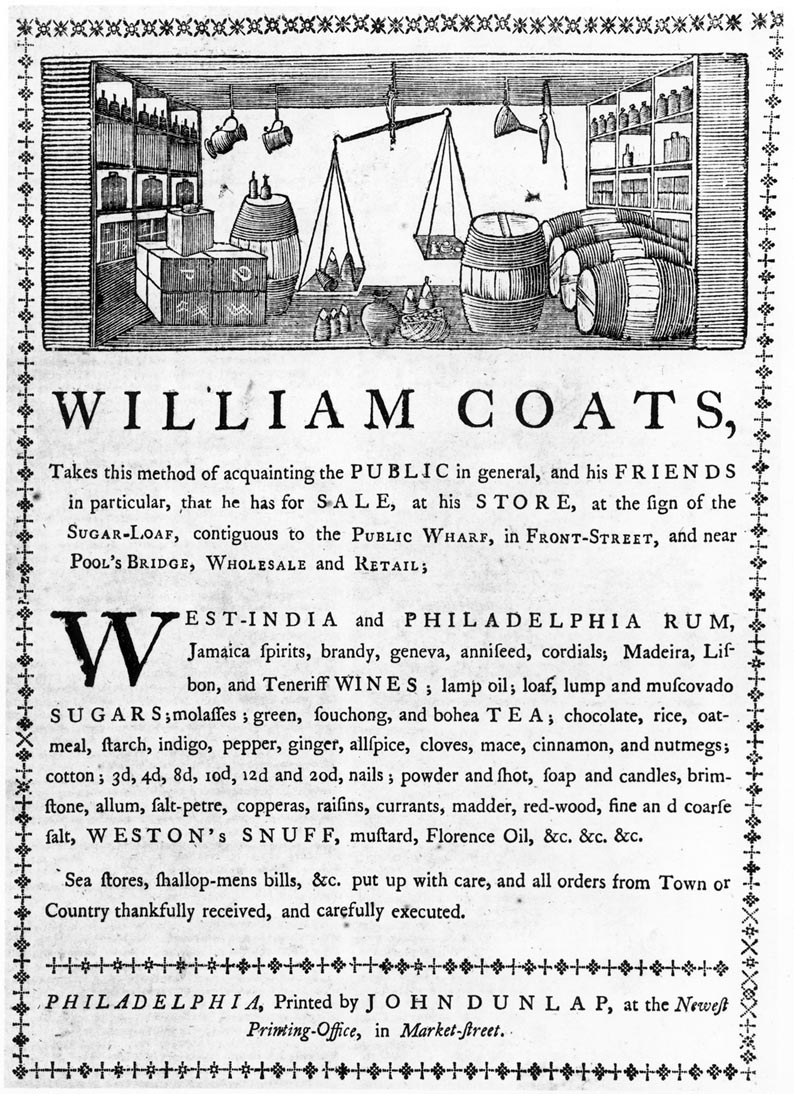

The Consumer Revolution

During the eighteenth century, Great Britain eclipsed the Dutch as the leading producer and trader of inexpensive consumer goods, including colonial products like coffee and tea, and such manufactured goods as linen, metalware, pins, ribbons, glassware, ceramics, and clothing. Trade integrated the British empire. As the American colonies were drawn more and more fully into the system of Atlantic commerce, they shared in the era’s consumer revolution. In port cities and small inland towns, shops proliferated and American newspapers were filled with advertisements for British goods. British merchants supplied American traders with loans to enable them to import these products, and traveling peddlers carried them into remote frontier areas.

Consumerism in a modern sense—the mass production, advertising, and sale of consumer goods—did not exist in colonial America. Nonetheless, eighteenth-century estate inventories—records of people’s possessions at the time of death—revealed the wide dispersal in American homes of European and even Asian products. In the seventeenth century, most colonists had lived in a pioneer world of homespun clothing and homemade goods. Now, even modest farmers and artisans owned books, ceramic plates, metal cutlery, and items made of imported silk and cotton. Tea, once a luxury enjoyed only by the wealthy, became virtually a necessity of life.

Colonial Cities

Britain’s mainland colonies were overwhelmingly agricultural. Nine-tenths of the population resided in rural areas and made their livelihood from farming. Colonial cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston were quite small by the standards of Europe or Spanish America. In 1700, when the population of Mexico City stood at 100,000, Boston had 6,000 residents and New York 4,500. As late as 1750, eight cities in Spanish America exceeded in size any in English North America.

English American cities served mainly as gathering places for agricultural goods and for imported items to be distributed to the countryside. Nonetheless, the expansion of trade encouraged the rise of port cities, home to a growing population of colonial merchants and artisans (skilled craftsmen) as well as an increasing number of poor. In 1770, with some 30,000 inhabitants, Philadelphia was, after London and Liverpool, the empire’s third-busiest port. The financial, commercial, and cultural center of British America, its growth rested on economic integration with the rich agricultural region nearby. Philadelphia merchants organized the collection of farm goods, supplied rural storekeepers, and extended credit to consumers. They exported flour, bread, and meat to the West Indies and Europe.

Colonial Artisans

Cities were also home to a large population of furniture makers, jewelers, and silversmiths serving wealthier citizens, and hundreds of lesser artisans like weavers, blacksmiths, coopers, and construction workers. The typical artisan owned his own tools and labored in a small workshop, often his home, assisted by family members and young journeymen and apprentices learning the trade. The artisan’s skill, which set him apart from the common laborers below him in the social scale, was the key to his existence, and it gave him a far greater degree of economic freedom than those dependent on others for a livelihood. “He that hath a trade, hath an estate,” wrote Benjamin Franklin, who had worked as a printer before achieving renown as a scientist and statesman.

Despite the influx of British goods, colonial craftsmen benefited from the expanding consumer market. Most journeymen enjoyed a reasonable chance of rising to the status of master and establishing a workshop of their own. Some achieved remarkable success. Born in New York City in 1723, Myer Myers, a Jewish silversmith of Dutch ancestry, became one of the city’s most prominent artisans. Myers produced jewelry, candlesticks, coffeepots, tableware, and other gold and silver objects for the colony’s elite, as well as religious ornaments for both synagogues and Protestant churches. He used some of his profits to acquire land in New Hampshire and Connecticut. Myers’s career reflected the opportunities colonial cities offered to skilled men of diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds.

An Atlantic World

People, ideas, and goods flowed back and forth across the Atlantic, knitting together the empire and its diverse populations and creating webs of interdependence among the European empires. Sugar, tobacco, deerskin leather, and other products of the Western Hemisphere were marketed as far away as Eastern Europe. London bankers financed the slave trade between Africa and Portuguese Brazil. Spain spent its gold and silver importing goods from other countries. As trade expanded, the North American and West Indian colonies became a major market. Like colonists, Native Americans bought British manufactured goods in return for furs and deerskins. Although most colonial output was consumed at home, North Americans shipped farm products to Britain, the West Indies, and, with the exception of goods like tobacco “enumerated” under the Navigation Acts, outside the empire. Virtually the entire Chesapeake tobacco crop was marketed in Britain, with most of it then re-exported to Europe by British merchants. Most of the bread and flour exported from the colonies was destined for the West Indies. Africans enslaved there grew sugar that could be distilled into rum, a product increasingly popular in North America. The mainland colonies carried on a flourishing trade in fish and grains with southern Europe. Ships built in New England made up one-third of the British empire’s trading fleet.

Membership in the empire had many advantages for the colonists. Most Americans did not complain about British regulation of their trade because commerce enriched the colonies as well as England and lax enforcement of the Navigation Acts allowed smuggling to flourish. In a dangerous world the Royal Navy protected American shipping. Eighteenth-century English America drew closer and closer to, and in some ways became more and more similar to, England itself.

Glossary

- redemptioners

- Indentured families or persons who received passage to the New World in exchange for a promise to work off their debt in America.

- Walking Purchase

- An infamous 1737 purchase of Native American land in which Pennsylvanian colonists tricked the Delaware Indians, who had agreed to cede land equivalent to the distance a man could walk in thirty-six hours, but the colonists marked out an area using a team of runners.

- backcountry

- In colonial America, the area stretching from central Pennsylvania southward through the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and into upland North and South Carolina.