RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION IN THE SOUTH

“The Tocsin of Freedom”

Among the former slaves, the passage of the Reconstruction Act inspired an outburst of political organization. At mass political meetings—community gatherings attended by men, women, and children—African Americans staked their claim to equal citizenship. Blacks, declared an Alabama meeting, deserved “exactly the same rights, privileges and immunities as are enjoyed by white men. We ask for nothing more and will be content with nothing less.”

These gatherings inspired direct action to remedy long-standing grievances. Hundreds took part in sit-ins that integrated horse-drawn public streetcars in cities across the South. Plantation workers organized strikes for higher wages. Speakers, male and female, fanned out across the South. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a black veteran of the abolitionist movement, embarked on a two-year tour, lecturing on “Literacy, Land, and Liberation.” She addressed her remarks to white southerners as well as emancipated slaves: “We are all bound up together in one great bundle of humanity, and society cannot trample on the weakest and feeblest of its members without receiving the curse in its own soul.”

Determined to exercise their new rights as citizens, thousands joined the Union League, an organization closely linked to the Republican Party, and the vast majority of eligible African Americans registered to vote. James K. Green, a former slave in Hale County, Alabama, and a League organizer, went on to serve eight years in the Alabama legislature. In the 1880s, Green looked back on his political career. Before the war, he declared, “I was entirely ignorant; I knew nothing more than to obey my master; and there were thousands of us in the same attitude. . . . But the tocsin [warning bell] of freedom sounded and knocked at the door and we walked out like free men and shouldered the responsibilities.”

By 1870, all the former Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union, and in a region where the Republican Party had not existed before the war, nearly all were under Republican control. Their new state constitutions, drafted in 1868 and 1869 by the first public bodies in American history with substantial Black representation, marked a considerable improvement over those they replaced. The constitutions established the region’s first state-funded systems of free public education and created new penitentiaries, orphan asylums, and homes for the insane. They guaranteed equality of civil and political rights and abolished practices of the antebellum era such as whipping as a punishment for crime, property qualifications for officeholding, and imprisonment for debt. A few states initially barred former Confederates from voting, but this policy was quickly abandoned by the new state governments.

The Black Officeholder

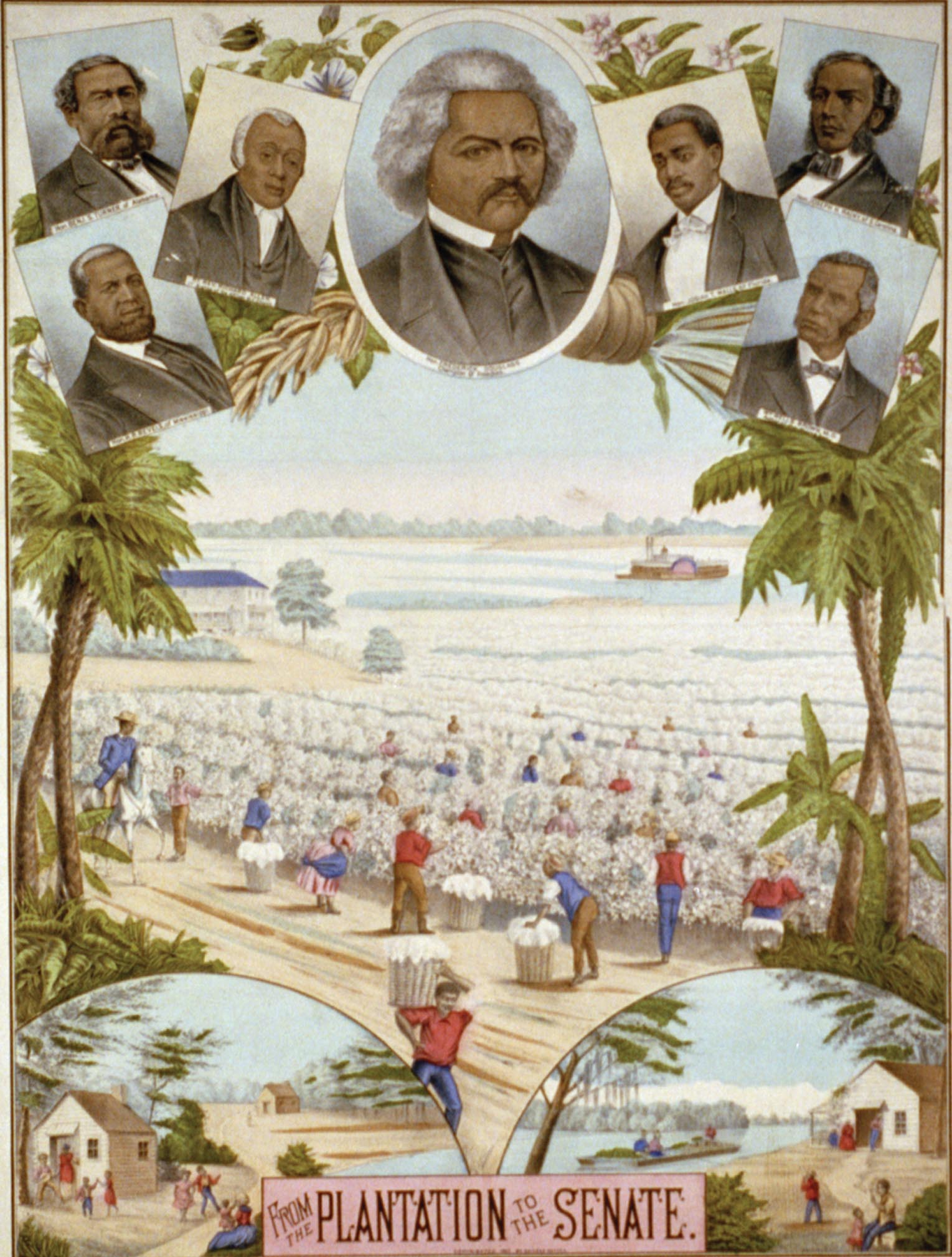

Throughout Reconstruction, Black voters provided the bulk of the Republican Party’s support. But African Americans did not control Reconstruction politics, as their opponents frequently charged. The highest offices remained almost entirely in white hands, and only in South Carolina, where Blacks made up 60 percent of the population, did they form a majority of the legislature. Nonetheless, the fact that some 2,000 African Americans occupied public offices during Reconstruction represented a fundamental shift of power in the South and a radical departure in American government.

African Americans were represented at every level of government. Fourteen were elected to the national House of Representatives. Two Blacks served in the U.S. Senate during Reconstruction, both representing Mississippi. Hiram Revels, who had been born free in North Carolina, was educated in Illinois, and served as a chaplain in the wartime Union army, in 1870 became the first Black senator in American history. The second, Blanche K. Bruce, a former slave, was elected in 1875. The next African American elected to the Senate was Edward W. Brooke of Massachusetts, who served 1967–1978.

Pinckney B. S. Pinchback of Louisiana, the Georgia-born son of a white planter and a free Black woman, served briefly during the winter of 1872–1873 as America’s first Black governor. More than a century would pass before L. Douglas Wilder of Virginia, elected in 1989, became the second. Some 700 Blacks sat in state legislatures during Reconstruction, and scores held local offices ranging from justice of the peace to sheriff, tax assessor, and policeman. The presence of Black officeholders and their white allies made a real difference in southern life, ensuring that Blacks accused of crimes would be tried before juries of their peers and enforcing fairness in such aspects of local government as road repair, tax assessment, and poor relief.

In South Carolina and Louisiana, homes of the South’s wealthiest and best-educated free Black communities, most prominent Reconstruction officeholders had never experienced slavery. In addition, a number of Black Reconstruction officials, like Pennsylvania-born Jonathan J. Wright, who served on the South Carolina Supreme Court, had come from the North after the Civil War. The majority, however, were former slaves who had established their leadership in the Black community by serving in the Union army, working as ministers, teachers, or skilled craftsmen, or engaging in Union League organizing. Among the most celebrated Black officeholders was Robert Smalls, who had worked as a slave on the Charleston docks before the Civil War and who won national fame in 1862 by secretly guiding the Planter, a Confederate vessel, out of the harbor and delivering it to Union forces. Smalls became a powerful political leader on the South Carolina Sea Islands and was elected to five terms in Congress.

Carpetbaggers and Scalawags

The new southern governments also brought to power new groups of whites. Many Reconstruction officials were northerners who for one reason or another made their homes in the South after the war. Their opponents dubbed them carpetbaggers, implying that they had packed all their belongings in a suitcase and left their homes in order to reap the spoils of office in the South. Some carpetbaggers were undoubtedly corrupt adventurers. The large majority, however, were former Union soldiers who decided to remain in the South when the war ended, before there was any prospect of going into politics. Others were investors in land and railroads who saw in the postwar South an opportunity to combine personal economic advancement with a role in helping to substitute, as one wrote, “the civilization of freedom for that of slavery.” Teachers, Freedmen’s Bureau officers, and others who came to the region genuinely hoping to assist the former slaves represented another large group of carpetbaggers.

Most white southern Republicans had been born in the South. Former Confederates reserved their greatest scorn for these scalawags, whom they considered traitors to their race and region. Some southern-born Republicans were men of stature and wealth, like James L. Alcorn, the owner of one of Mississippi’s largest plantations and the state’s first Republican governor.

Most scalawags, however, were non-slaveholding white farmers from the southern upcountry. Many had been wartime Unionists, and they now cooperated with the Republicans in order to prevent “rebels” from returning to power. Others hoped Reconstruction governments would help them recover from wartime economic losses by suspending the collection of debts and enacting laws protecting small property holders from losing their homes to creditors. In states like North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas, Republicans initially commanded a significant minority of the white vote. Even in the Lower South, the small white Republican vote was important, because the population remained almost evenly divided between Blacks (almost all of whom voted for the party of Lincoln) and whites (overwhelmingly Democratic).

Southern Republicans in Power

In view of the daunting challenges they faced, the remarkable thing is not that Reconstruction governments in some respects failed, but how much they did accomplish. Perhaps their greatest achievement lay in establishing the South’s first state-supported public schools. The new educational systems served both Black and white children, although generally in schools segregated by race. Only in New Orleans were the public schools integrated during Reconstruction, and only in South Carolina did the state university admit Black students (elsewhere, separate colleges were established). By the 1870s, in a region whose prewar leaders had made it illegal for slaves to learn and had done little to provide education for poorer whites, more than half the children, Black and white, were attending public schools. The new governments also pioneered civil rights legislation. Their laws made it illegal for railroads, hotels, and other institutions to discriminate on the basis of race. Enforcement varied considerably from locality to locality, but Reconstruction established for the first time at the state level a standard of equal citizenship and a recognition of Blacks’ right to a share of public services.

Republican governments also took steps to strengthen the position of rural laborers and promote the South’s economic recovery. They passed laws to ensure that agricultural laborers and sharecroppers had the first claim on harvested crops, rather than merchants to whom the landowner owed money. South Carolina created a state Land Commission, which by 1876 had settled 14,000 Black families and a few poor whites on their own farms.

The Quest for Prosperity

Rather than land distribution, however, the Reconstruction governments pinned their hopes for southern economic growth and opportunity for African Americans and poor whites alike on regional economic development. Railroad construction, they believed, was the key to transforming the South into a society of booming factories, bustling towns, and diversified agriculture. “A free and living republic,” declared a Tennessee Republican, would “spring up in the track of the railroad.” Every state during Reconstruction helped to finance railroad construction, and through tax reductions and other incentives tried to attract northern manufacturers to invest in the region. The program had mixed results. Economic development in general remained weak. With abundant opportunities existing in the West, few northern investors ventured to the Reconstruction South.

To their supporters, the governments of Radical Reconstruction presented a complex pattern of disappointment and accomplishment. A revitalized southern economy failed to materialize, and most African Americans remained locked in poverty. On the other hand, biracial democratic government, a thing unknown in American history, for the first time functioned effectively in many parts of the South. Public facilities were rebuilt and expanded, school systems established, and legal codes purged of racism. The conservative elite that had dominated southern government from colonial times to 1867 found itself excluded from political power, while poor whites, newcomers from the North, and former slaves cast ballots, sat on juries, and enacted and administered laws. “We have gone through one of the most remarkable changes in our relations to each other,” declared a white South Carolina lawyer in 1871, “that has been known, perhaps, in the history of the world.” It is a measure of how far change had progressed that the reaction against Reconstruction proved so extreme.

Glossary

- carpetbaggers

- Derisive term for northern emigrants who participated in the Republican governments of the Reconstruction South.

- scalawags

- Southern white Republicans—some former Unionists—who supported Reconstruction governments.