![]() Ideas of Industrial Expansion in the Late Nineteenth Century

Ideas of Industrial Expansion in the Late Nineteenth Century

THE SECOND INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Between the end of the Civil War and the early twentieth century, the United States underwent one of the most rapid and profound economic revolutions any country has ever experienced. There were numerous causes for this explosive economic growth. The country enjoyed abundant natural resources, a growing supply of labor, an expanding market for manufactured goods, and the availability of capital for investment. In addition, the federal government actively promoted industrial and agricultural development. It enacted high tariffs that protected American industry from foreign competition, granted land to railroad companies to encourage construction, and used the army to remove Indians from western lands desired by farmers and mining companies.

The Industrial Economy

The rapid expansion of factory production, mining, and railroad construction in all parts of the country except the South signaled the transition from Lincoln’s America—a world centered on the small farm and artisan workshop—to a mature industrial society. Americans of the late nineteenth century marveled at the triumph of the new economy. “One can hardly believe,” wrote the philosopher John Dewey, “there has been a revolution in history so rapid, so extensive, so complete.”

By 1913, the United States produced one-third of the world’s industrial output—more than the total of Great Britain, France, and Germany combined. Half of all industrial workers now labored in plants with more than 250 employees. On the eve of the Civil War, the first industrial revolution, centered on the textile industry, had transformed New England into a center of manufacturing. But otherwise, the United States was still primarily an agricultural nation. By 1880, for the first time, the Census Bureau found a majority of the workforce engaged in non-farming jobs. By 1890, two-thirds of Americans worked for wages, rather than owning a farm, business, or craft shop. Drawn to factories by the promise of employment, a new working class emerged in these years. Between 1870 and 1920, almost 11 million Americans moved from farm to city, and another 25 million immigrants arrived from overseas.

TABLE 16.1 Indicators of Economic Change, 1870–1920

|

1870 |

1900 |

1920 |

|

|

Farms (millions) |

2.7 |

5.7 |

6.4 |

|

Land in farms (million acres) |

408 |

841 |

956 |

|

Wheat grown (million bushels) |

254 |

599 |

843 |

|

Employment (millions) |

14 |

28.5 |

44.5 |

|

In manufacturing (millions) |

2.5 |

5.9 |

11.2 |

|

Percentage in workforcea |

|||

|

Agricultural |

52 |

38 |

27 |

|

Industryb |

29 |

31 |

44 |

|

Trade, service, administrationc |

20 |

31 |

27 |

|

Railroad track (thousands of miles) |

53 |

258 |

407 |

|

Steel produced (thousands of tons) |

0.8 |

11.2 |

46 |

|

Gross national product (billions of dollars) |

7.4 |

18.7 |

91.5 |

|

Per capita (in 1920 dollars) |

371 |

707 |

920 |

|

Life expectancy at birth (years) |

42 |

47 |

54 |

|

a Percentages are rounded and do not total 100. b Includes manufacturing, transportation, mining, and construction. c Includes trade, finance, and public administration. |

|||

Most manufacturing now took place in industrial cities. New York, with its new skyscrapers and hundreds of thousands of workers in all sorts of manufacturing establishments, symbolized dynamic urban growth. After merging with Brooklyn in 1898, its population exceeded 3.4 million. The city, along with Boston, financed industrialization and westward expansion, its banks and stock exchange funneling capital to railroads, mines, and factories. But the heartland of the second industrial revolution was the region around the Great Lakes, with its factories producing iron and steel, machinery, chemicals, and packaged foods. Pittsburgh had become the world’s center of iron and steel manufacturing. Chicago, by 1900 the nation’s second-largest city, with 1.7 million inhabitants, was home to factories producing steel and farm machinery and giant stockyards where cattle were processed into meat products for shipment east in refrigerated railcars. Smaller industrial cities also proliferated, often concentrating on a single industry—cast-iron stoves in Troy, New York, furniture in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Forging the Shaft a painting from the 1870s by the American artist John Ferguson Weir, depicts workers in a steel factory making a propeller shaft for an ocean liner. Weir illustrates both the dramatic power of the factory at a time when the United States was overtaking European countries in manufacturing and the fact that industrial production still required hard physical labor.

A painting by Edward Moran captures the excitement at the unveiling of the Statue of Liberty in 1886.

Railroads and the National Market

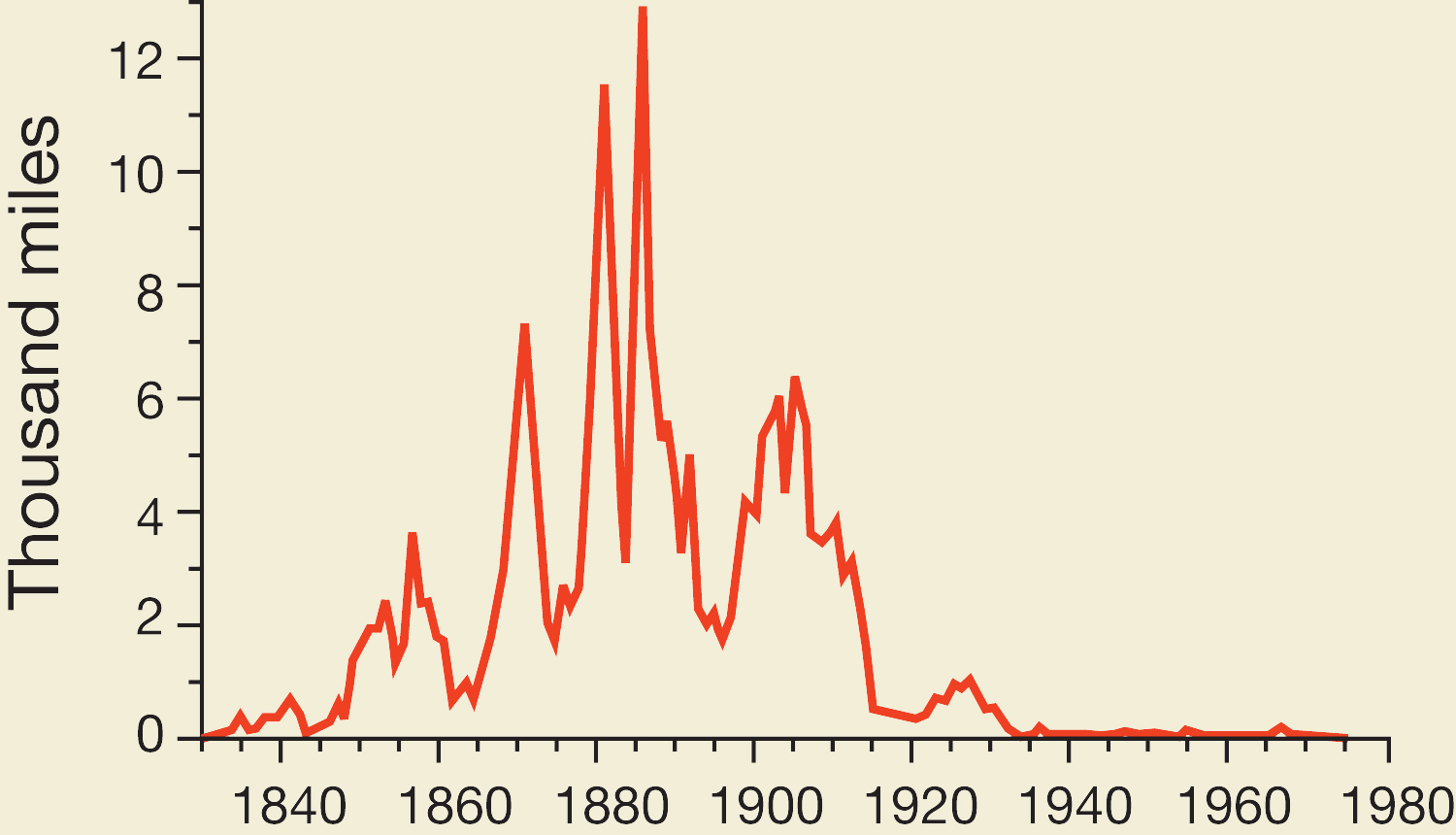

The railroad made possible what is sometimes called the “second industrial revolution.” Spurred by private investment and massive grants of land and money by federal, state, and local governments, the number of miles of railroad track in the United States tripled between 1860 and 1880 and tripled again by 1920, opening vast new areas to commercial farming and creating a truly national market for manufactured goods. In 1886, the railroads adopted a standard national gauge (the distance separating the two rails), making it possible for the first time for trains of one company to travel on any other company’s track. By the 1890s, five transcontinental lines transported the products of western mines, farms, ranches, and forests to eastern markets and carried manufactured goods to the West. The railroads reorganized time itself. In 1883, the major companies divided the nation into the four time zones still in use today.

By 1880, the transnational rail network made possible the creation of a truly national market for goods.

FIGURE 16.1 Railroad Mileage Built, 1830–1975

The growing population formed an ever-expanding market for the mass production, mass distribution, and mass marketing of goods, essential elements of a modern industrial economy. The spread of national brands like Ivory soap and Quaker Oats symbolized the continuing integration of the economy. So did the growth of national chains, most prominently the Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, better known as A & P grocery stores. Based in Chicago, the national mail-order firms Montgomery Ward and Sears, Roebuck & Co. sold clothing, jewelry, farm equipment, and numerous other goods to rural families throughout the country.

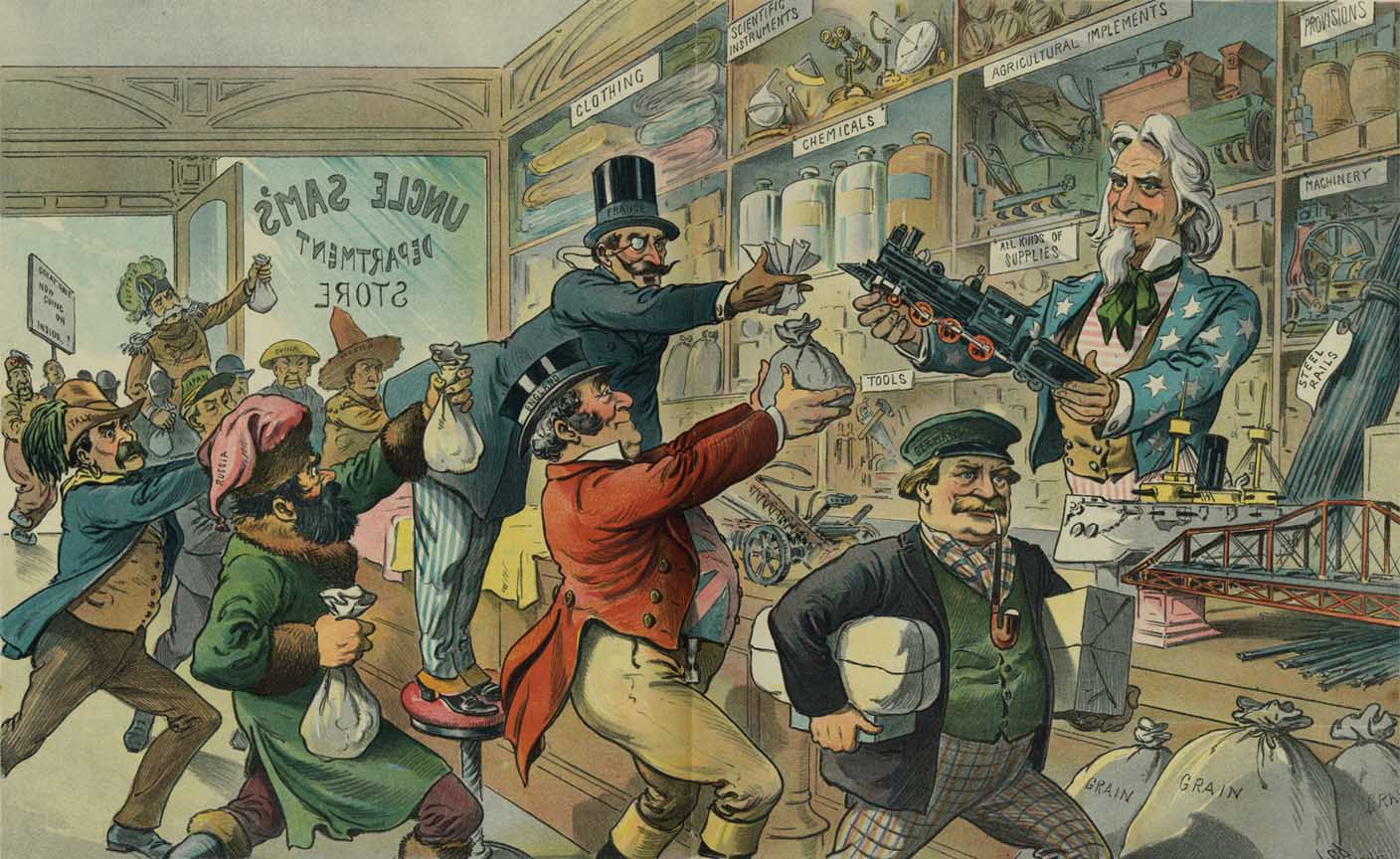

VISIONS OF FREEDOM

The Greatest Department Store on Earth

The Spirit of Innovation

A remarkable series of technological innovations spurred rapid communication and economic growth. The opening of the Atlantic cable in 1866 made it possible to send electronic telegraph messages instantaneously between the United States and Europe. During the 1870s and 1880s, the telephone, typewriter, and handheld camera came into use.

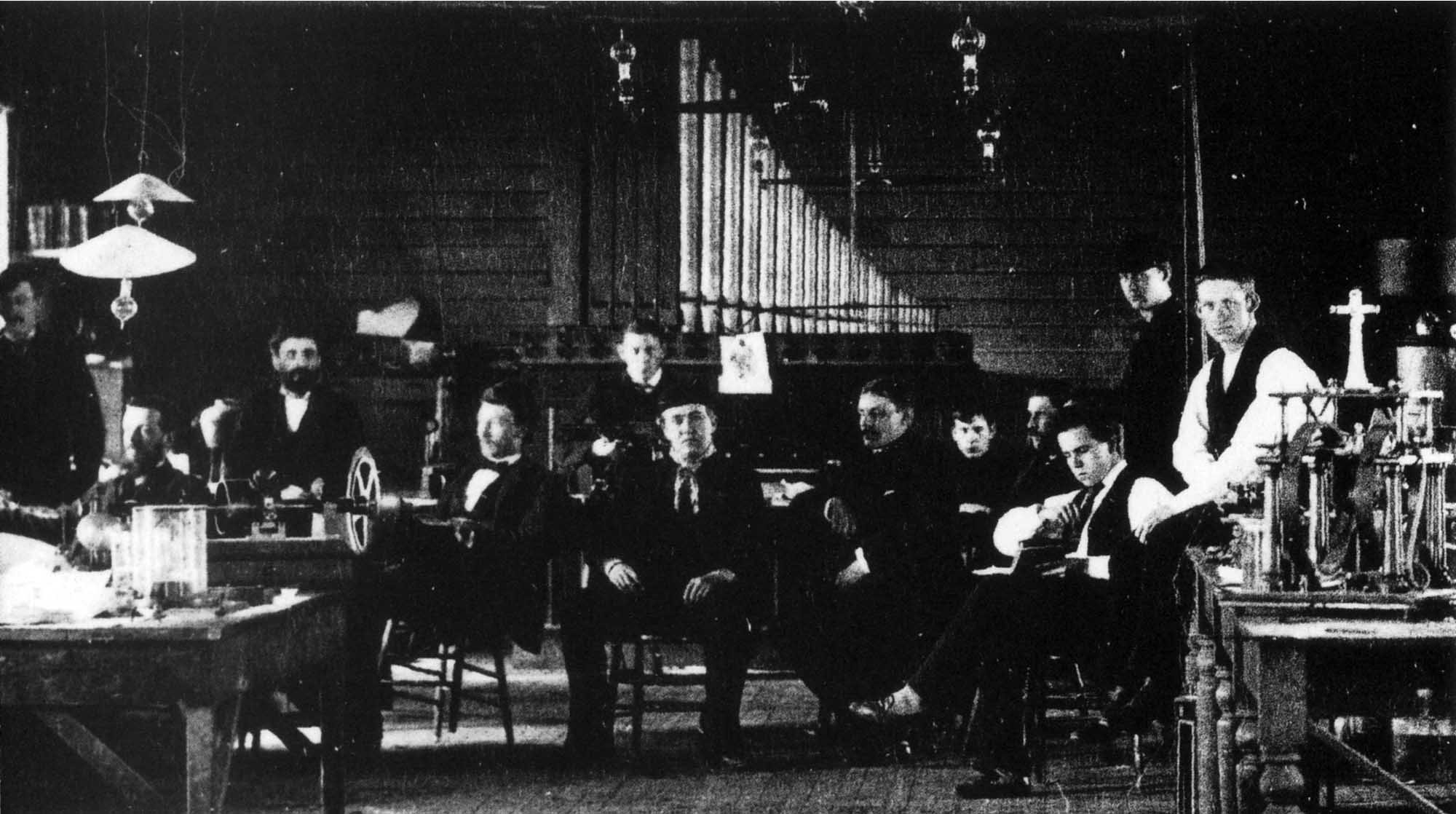

Scientific breakthroughs poured forth from research laboratories in Menlo Park and West Orange, New Jersey, created by the era’s greatest inventor, Thomas A. Edison. During the course of his life, Edison helped to establish entirely new industries that transformed private life, public entertainment, and economic activity, including the phonograph, lightbulb, motion picture, and a system for generating and distributing electric power. He opened the first electric generating station in Manhattan in 1882 to provide power to streetcars, factories, and private homes, and he established, among other companies, the forerunner of General Electric to market electrical equipment. The spread of electricity was essential to industrial and urban growth, providing a more reliable and flexible source of power than water or steam.

Thomas Edison’s laboratory at Menlo Park, New Jersey, and some of the employees of the great inventor.

Competition and Consolidation

Economic growth was dramatic but highly volatile. The combination of a market flooded with goods and the federal monetary policies (discussed later in this chapter) that removed money from the national economy led to a relentless fall in prices. The world economy suffered prolonged downturns in the 1870s and 1890s.

Businesses engaged in ruthless competition. Railroads and other companies tried various means of bringing order to the chaotic marketplace. They formed “pools” that divided up markets between supposedly competing firms and fixed prices. They established trusts—legal devices whereby the affairs of several rival companies were managed by a single director. Such efforts to coordinate the economic activities of independent companies generally proved short-lived, disintegrating as individual firms continued their intense pursuit of profits.

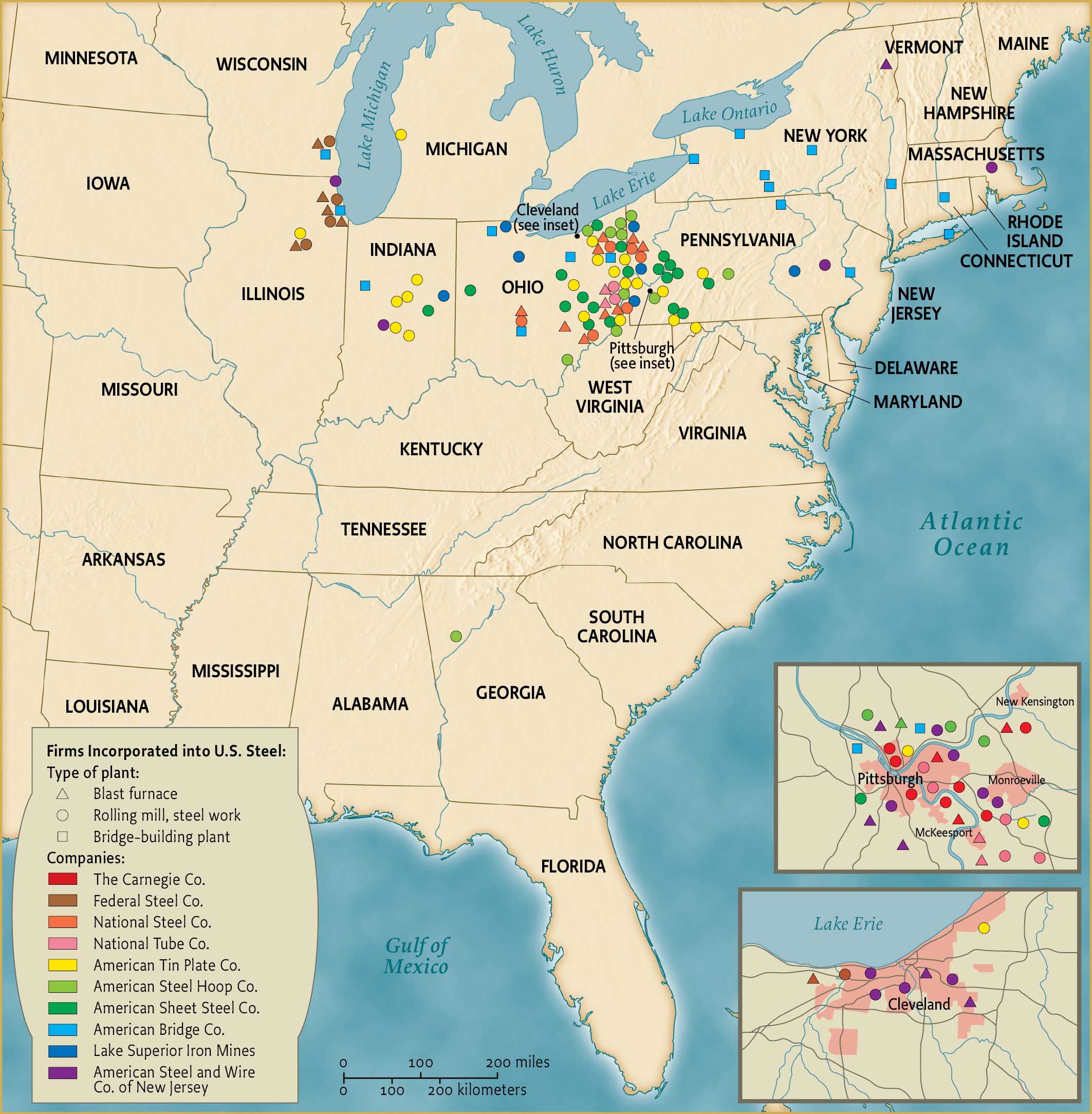

To avoid cutthroat competition, more and more corporations battled to control entire industries. The process of economic concentration culminated between 1897 and 1904, when some 4,000 firms vanished into larger corporations that served national markets and exercised an unprecedented degree of control over the economy. By the time the wave of mergers had been completed, giant corporations like U.S. Steel (created by financier J. P. Morgan in 1901 by combining ten large steel companies into the first billion-dollar economic enterprise), Standard Oil, and International Harvester (a manufacturer of agricultural machinery) dominated major industries.

The Rise of Andrew Carnegie

In an era without personal or corporate income taxes, some business leaders accumulated enormous fortunes and economic power. Under the aggressive leadership of Thomas A. Scott, the Pennsylvania Railroad—for a time the nation’s largest corporation—forged an economic empire that stretched across the continent and included coal mines and oceangoing steamships. With an army of professional managers to oversee its far-flung activities, the railroad pioneered modern techniques of business organization.

Another industrial giant was Andrew Carnegie, who emigrated with his family from his native Scotland at the age of thirteen and as a teenager worked in a Pennsylvania textile factory. During the depression that began in 1873, Carnegie set out to establish a steel company that incorporated vertical integration—that is, one that controlled every phase of the business from raw materials to transportation, manufacturing, and distribution. By the 1890s, he dominated the steel industry and had accumulated a fortune worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Carnegie’s complex of steel factories at Homestead, Pennsylvania, was the most technologically advanced in the world.

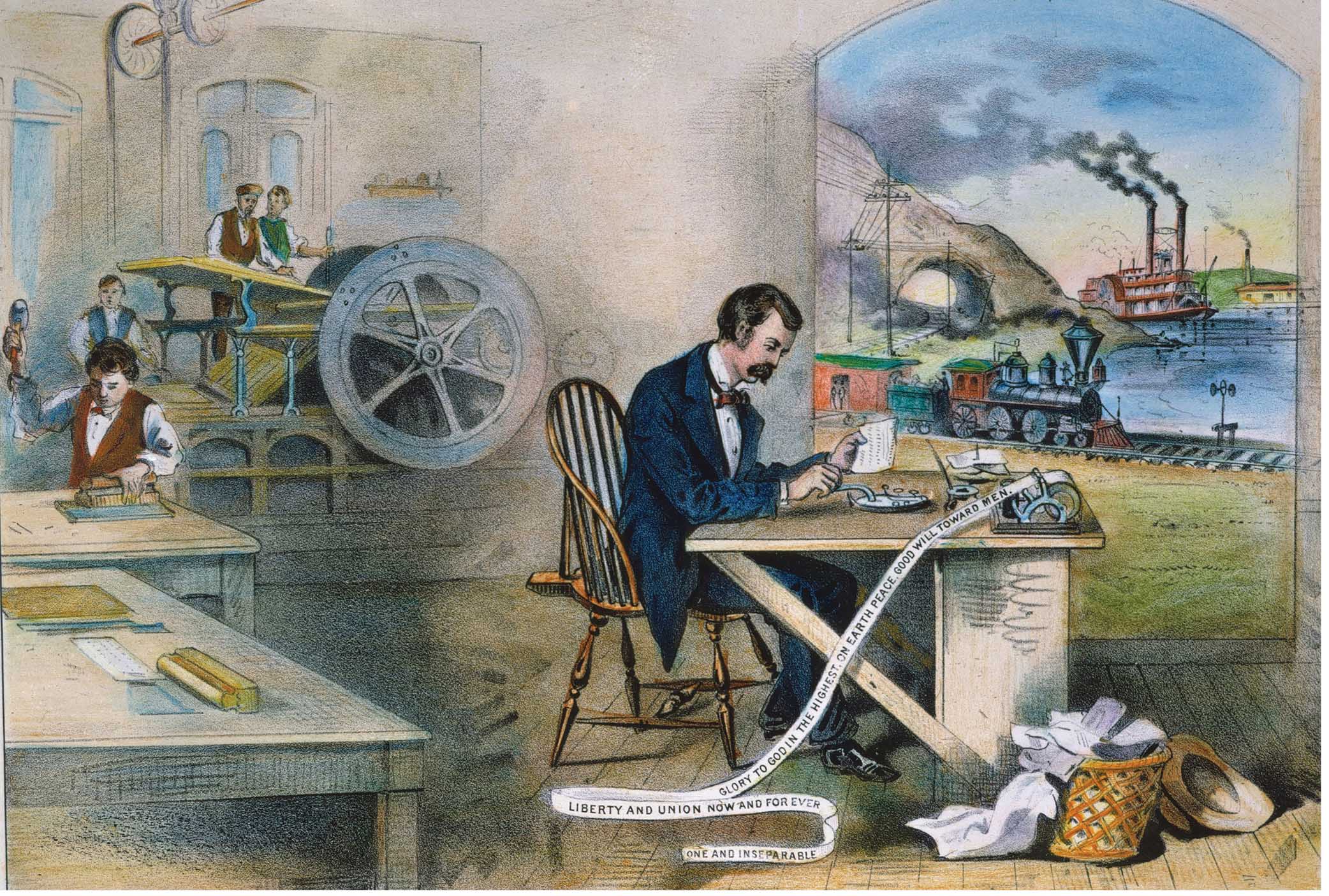

The Progress of the Century, a lithograph from 1876, celebrates four of the major technological innovations of the century since American independence: the steamboat, locomotive, steam press, and telegraph.

Carnegie’s father, an immigrant Scottish weaver who had taken part in popular efforts to open the British political system to working-class participation, had instilled in his son a commitment to democracy and social equality. From his mother, Carnegie learned that life was a ceaseless struggle in which one must strive to get ahead or sink beneath the waves. His life reflected the tension between these elements of his upbringing. Believing that the rich had a moral obligation to promote the advancement of society, Carnegie denounced the “worship of money” and distributed much of his wealth to various philanthropies, especially the creation of public libraries in towns throughout the country. But he ran his companies with a dictatorial hand. His factories operated nonstop, with two twelve-hour shifts every day of the year except the Fourth of July. Carnegie’s rise from humble beginnings to great wealth reinforced the “rags to riches” ideal that flourished during the Gilded Age. But such success was hardly available to his own poorly paid employees.

The Electricity Building at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893, painted by Childe Hassam. The electric lighting at the fair astonished visitors and illustrated how electricity was changing the visual landscape.

The Triumph of John D. Rockefeller

If any single name became a byword for enormous wealth, it was John D. Rockefeller, who began his working career as a clerk for a Cleveland merchant and rose to dominate the oil industry. He drove out rival firms through cutthroat competition, arranging secret deals with railroad companies, and fixing prices and production quotas. Rockefeller began with horizontal expansion—buying out competing oil refineries. But like Carnegie, he soon established a vertically integrated monopoly, which dominated the drilling, refining, storage, and distribution of oil. By the 1880s, his Standard Oil Company controlled 90 percent of the nation’s oil industry. Like Carnegie, Rockefeller gave much of his fortune away, establishing foundations to promote education and medical research. And like Carnegie, he bitterly fought his employees’ efforts to organize unions.

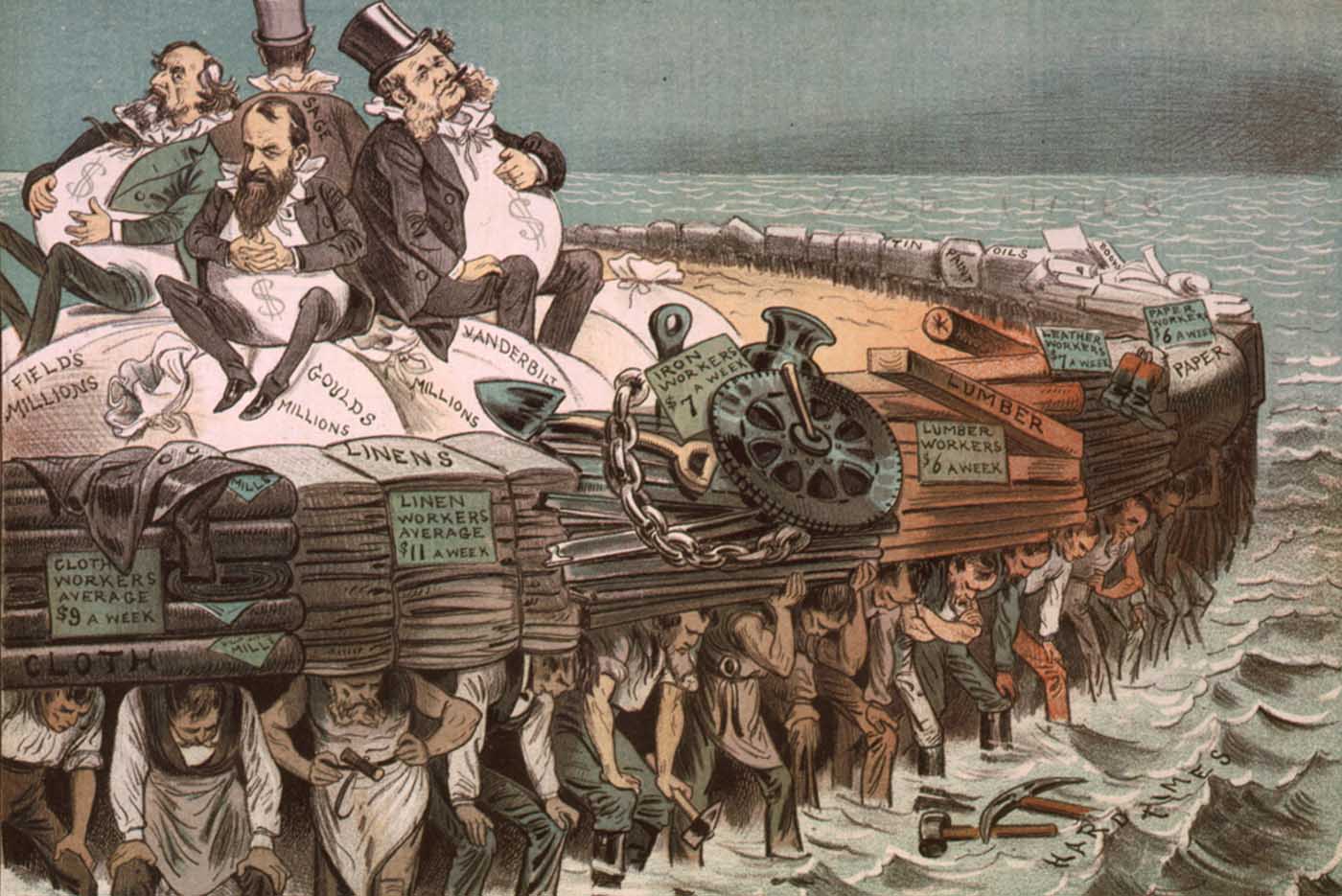

A cartoon in the satirical magazine Puck, February 7, 1883, shows robber barons Jay Gould, Cyrus Field, Russell Sage, and Cornelius Vanderbilt seated on a raft with their “millions,” while workers from various occupations keep them afloat.

These and other industrial leaders inspired among ordinary Americans a combination of awe, admiration, and hostility. Depending on one’s point of view, they were “captains of industry,” whose energy and vision pushed the economy forward, or “robber barons,” who wielded power without any accountability in an unregulated marketplace. Most rose from modest backgrounds and seemed examples of how inventive genius and business sense enabled Americans to seize opportunities for success. But their dictatorial attitudes, unscrupulous methods, repressive labor policies, and exercise of power without any democratic control led to fears that they were undermining political and economic freedom. Concentrated wealth degraded the political process, declared Henry Demarest Lloyd in Wealth against Commonwealth (1894), an exposé of how Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company made a mockery of economic competition and political democracy by manipulating the market and bribing legislators. “Liberty and monopoly,” Lloyd concluded, “cannot live together.”

Workers’ Freedom in an Industrial Age

![]() Ideas of Freedom following the Civil War

Ideas of Freedom following the Civil War

Remarkable as it was, the country’s economic growth distributed its benefits very unevenly. For a minority of workers, the rapidly expanding industrial system created new forms of freedom. In some industries, skilled workers commanded high wages and exercised considerable control over the production process. A worker’s economic independence now rested on technical skill rather than ownership of one’s own shop and tools as in earlier times. What was known as “the miner’s freedom” consisted of elaborate work rules that left skilled underground workers free of managerial supervision on the job. Through their union, skilled iron- and steelworkers fixed output quotas and controlled the training of apprentices in the technique of iron rolling. These workers often knew more about the details of production than their employers did.

The music room of The Breakers, the opulent mansion of millionaire Cornelius Vanderbilt II in Newport, Rhode Island, an exclusive retreat for rich socialites of the Gilded Age.

Such “freedom,” however, applied only to a tiny portion of the industrial labor force and had little bearing on the lives of the growing army of semiskilled workers who tended machines in the new factories. For most workers, economic insecurity remained a basic fact of life. During the depressions of the 1870s and 1890s, millions of workers lost their jobs or were forced to accept reductions of pay. The “tramp” became a familiar figure on the social landscape as thousands of men took to the roads in search of work. Many industrial workers labored sixty-hour weeks with no pensions, compensation for injuries, or protections against unemployment. Although American workers received higher wages than their counterparts in Europe, they also experienced more dangerous working conditions. Between 1880 and 1900, an average of 35,000 workers perished each year in factory and mine accidents, the highest rate in the industrial world.

In 1888, the Chicago Times published a series of articles by reporter Nell Cusack under the title “City Slave Girls,” exposing wretched conditions among women working for wages in the city’s homes, factories, and sweatshops. The articles unleashed a flood of letters to the editor from women workers. One singled out domestic service—still the largest employment category for women—as “a slave’s life,” with “long hours, late and early, seven days in the week, bossed and ordered about as before the war.”

Increasing Wealth and Poverty

At the other end of the economic spectrum, the era witnessed an unprecedented accumulation of wealth. Class divisions became more and more visible. In frontier days, all classes in San Francisco, for example, lived near the waterfront. In the late nineteenth century, upper-class families built mansions on Nob Hill and Van Ness Avenue (known as “millionaire’s row”). In eastern cities as well, the rich increasingly resided in their own exclusive neighborhoods and vacationed among members of their own class at exclusive resorts like Newport, Rhode Island. The growing urban middle class of professionals, office workers, and small businessmen moved to new urban and suburban neighborhoods linked to central business districts by streetcars and commuter railways. “Passion for money,” wrote the novelist Edith Wharton in The House of Mirth (1905), dominated society. Wharton’s book traced the difficulties of Lily Bart, a young woman of modest means pressured by her mother and New York high society to “barter” her beauty for marriage to a rich husband.

In Palo Alto Spring (1878), a portrait of upper-class life in Gilded Age America by the artist Thomas Hill, the family and friends of railroad magnate Leland Stanford (shown with a painting on his lap) gather at the Stanford farm in Palo Alto, California, today the site of Stanford University. The painting originally hung in the Stanfords’ San Francisco mansion, which was destroyed by an earthquake in 1906.

By 1890, the richest 1 percent of Americans received the same total income as the bottom half of the population and owned more property than the remaining 99 percent. Many of the wealthiest Americans consciously pursued an aristocratic lifestyle, building palatial homes, attending exclusive social clubs, schools, and colleges, holding fancy-dress balls, and marrying into each other’s families. In 1899, the economist and social historian Thorstein Veblen published The Theory of the Leisure Class, a devastating critique of an upper-class culture focused on “conspicuous consumption”—that is, spending money not on needed or even desired goods, but simply to demonstrate the possession of wealth. One of the era’s most widely publicized spectacles was an elaborate costume ball organized in 1897 by Mrs. Bradley Martin, the daughter of a New York railroad financier. The theme was the royal court of prerevolutionary France. The Waldorf-Astoria Hotel was decorated to look like the palace of Versailles, the guests wore the dress of the French nobility, and the hostess bedecked herself with the actual jewels of Queen Marie Antoinette.

Not that far from the Waldorf, much of the working class lived in desperate conditions. Jacob Riis, in How the Other Half Lives (1890), offered a shocking account of living conditions among the urban poor, complete with photographs of apartments in dark, airless, overcrowded tenement houses.

Glossary

- trusts

- Companies combined to limit competition.

- vertical integration

- Company’s avoidance of intermediaries by producing its own supplies and providing for distribution of its product.

- horizontal expansion

- The process by which a corporation acquires or merges with its competitors.

- robber barons

- Also known as “captains of industry”; Gilded Age industrial figures who inspired both admiration, for their economic leadership and innovation, and hostility and fear, due to their unscrupulous business methods, repressive labor practices, and unprecedented economic control over entire industries.