How Does Federalism Work?

★ Describe the major theories and mechanisms of American federalism

There has not been a singular theory of how federalism works in the United States. Over time, there have been different ideas about federalism and different mechanisms for putting those ideas into practice.

Dual Federalism

Following the end of Reconstruction and into the early twentieth century, the court embraced dual federalism, which was described by political scientist Morton Grodzins as layer-cake federalism (see Figure 3.1). Like the layers on a cake, the powers of the national government and state governments were largely separate and, one might add, the layer representing the national government’s powers and responsibilities was smaller than the layer that represented the powers and responsibilities of state governments.30 Under dual federalism, there were still clear limits to the sovereignty of states. States could not nullify national legislation, nor could they secede from the Union, but states had a major role to play in governance that was quite distinct from the role of the federal government.

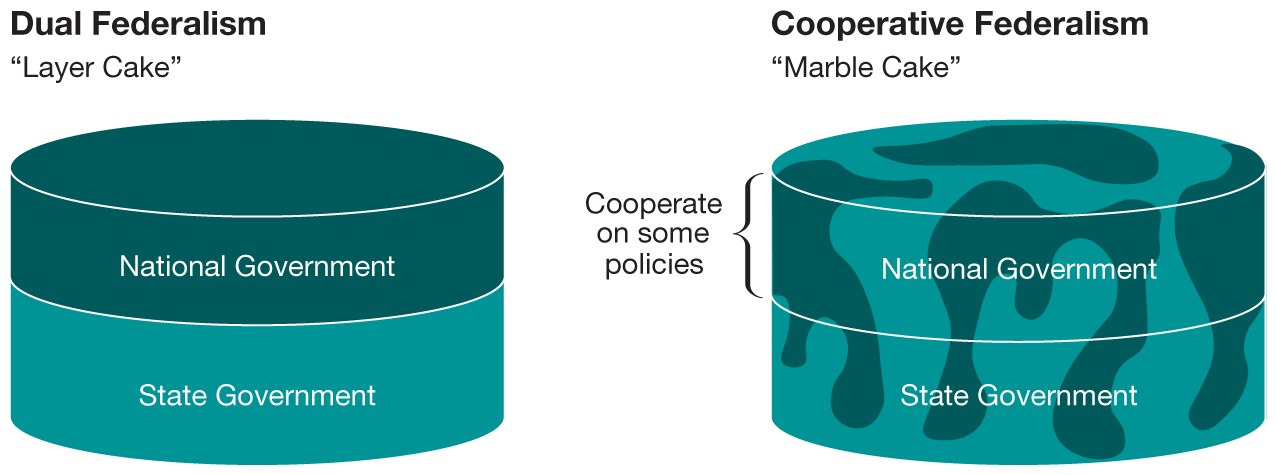

FIGURE 3.1

Dual versus Cooperative Federalism

In layer-cake federalism, the responsibilities of the national government and state governments are clearly separated. In marble-cake federalism, national policies and state policies overlap in many areas.

More information

Figure 3.1 titled Dual versus Cooperative Federalism is a diagram that compares dual federalism and cooperative federalism. A paragraph reads: In layer-cake federalism, the responsibilities of the national government and state governments are clearly separated. In marble-cake federalism, national policies and state policies overlap in many areas.

The diagram represents each type of federalism as a cake. Dual federalism is a layer cake, with the national government on top and the state governments on the bottom. Cooperative federalism is a marble cake with the national and state governments “swirled” together, showing that they cooperate in some national policies.

Prior to the late 1930s the Supreme Court was using dual federalism to strike down regulation of the economy by the national government. Congressional power to regulate interstate commerce was narrowly defined, Congress was powerless to forbid the distribution of the products of child labor in interstate commerce, and it could not regulate aspects of the manufacture of goods, such as monopolies on production or working conditions in factories.

Dual federalism had tremendous effects on Texas. For example, the Railroad Commission of Texas established rules that, among other things, limited the number of oil wells that could be drilled on a particular amount of land and the amount of oil that could be pumped from those wells. Such regulations were seen as a matter for state rather than national regulation until the discovery of the East Texas Oil Field in 1930, which then was the largest oil field in the world. As a result of this discovery, such overproduction of oil occurred that national legislation was needed to prevent an interstate market in oil produced in violation of state regulations.

Dual federalism was also used to prevent national intervention into acts of racial violence in Texas, because enforcement of criminal laws was seen as a state matter. Texas did pass an anti-lynching law in 1897 that was used to prevent some lynchings by authorizing the governor to call out the state guard. Nevertheless, Texas and other states were remarkably ineffective in preventing lynching. It is hard to identify the precise number of victims, but the Equal Justice Initiative has identified 3,959 lynchings between 1877 and 1950 whose purpose was to enforce racial separation and segregation laws. Of those, 376 occurred in Texas.31 It was only in the 1960s that national laws began to be used to successfully prosecute these crimes.

DUAL SOVEREIGNTY Dual sovereignty is not to be confused with dual federalism. Dual sovereignty means that both state governments and the national government have powers to make laws. The national government’s power is limited to the lawmaking authority granted in the Constitution to the national government. The lawmaking authority of state government is the police power—the power of states to pass laws to promote the health, safety, and welfare of people. As long as the state can show it is reasonably exercising its police power, it has the authority to, for example, require businesses to close or people to wear masks in public in order to reduce the spread of the coronavirus.

Sometimes the national government passes laws that regulate or forbid actions that are also regulated or forbidden by state laws. In such a situation, the question often becomes whether a person charged with a state crime can also be charged with the same crime under federal laws. That situation happened to Terance Gamble, who pled guilty to a state charge of violating Alabama’s law against a felon possessing a firearm. Then federal prosecutors charged Gamble with the federal crime involving a felon possessing a firearm. Gamble took his case all the way to the Supreme Court arguing that he was being tried for the same crime twice, which was double jeopardy and violated that provision of the Fifth Amendment. The Court, however, cited 170 years of Court precedent in explaining that the United States is not a unitary government. Instead, it is a federal system where both the state and the national government have the power to pass laws and so Alabama could prosecute and convict Gamble for the firearm charge and the federal government could do so as well without any problem of double jeopardy.32

Cooperative Federalism

With the presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1933–45)—when America faced the Great Depression and then World War II—the relationship between the national government and the states changed dramatically. This new relationship was called cooperative federalism, or marble-cake federalism, in which the boundaries between the national and state governments became blurred. In the initial form of cooperative federalism, national and state governments worked together to provide services—often with joint funding of programs or state administration of programs mostly funded by the national government.

More information

Two flags flying in front of the Texas state capitol: the American flag and the Texas state flag.

The U.S. and Texas flags that fly in front of many government buildings in Texas (including the Texas State Capitol, pictured here) reflect the nature of federalism. Both the national government and the state government are sovereign.

In fighting the Great Depression, Roosevelt pursued a variety of such programs. The Social Security Act of 1935, for instance, changed the existing system of federalism in a number of fundamental ways. First, it put into place a national insurance program for the elderly, wherein individuals in all states were assessed a payroll tax on their wages and upon retirement received a pension check. Second, the act put into place a series of state-federal programs to address particular social problems, including unemployment insurance, aid to dependent children, aid to blind and disabled people, and aid to impoverished elderly people. The basic model for these programs was that the federal government would make money available to states that established their own programs in these areas, provided they met specific administrative guidelines. Although the federal dollars came with these strings attached, the programs were state run and could differ from state to state. This type of funding system was common in the early days of cooperative federalism. The federal grants made using this model were called categorical grants. During the New Deal period, the idea was abandoned that the Tenth Amendment was a barrier to national power and that the national government could not involve itself in areas that had previously been reserved only to the states.

In the 1960s, during the Great Society policies of President Lyndon B. Johnson, a former U.S. senator from Texas, new programs were added to the Social Security Act. Medicare was established to provide health insurance for the elderly, paid for through a payroll tax on current workers. Medicaid was added to provide health care funding for individuals enrolled in the state-federal Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program. Medicaid’s funding and administration were based on the same state-federal principles as AFDC and unemployment insurance: the federal government provided funding for approved state programs. Federalism continued to evolve with the passage of civil rights legislation in the 1950s and ’60s, when the role of the national government was expanded to protect the rights of people of color. In the process, the national government was often thrown into conflict with southern states such as Texas that persisted in trying to maintain a segregated society.

After his election in 1968, President Richard M. Nixon briefly tried to reduce the power of the national government and increase that of the states with a program known as New Federalism. Nixon introduced a funding mechanism called block grants, which allowed the states considerable leeway in spending their federal dollars. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan adopted Nixon’s New Federalism as his own, and block grants became an important part of state-federal cooperation.

New Federalism’s biggest success, however, came during President Bill Clinton’s administration, when in 1996 major reforms were passed that gave the states a significant decision-making role in welfare programs. By the 1990s liberals and conservatives agreed that welfare in America was broken. Replacing the state-federal system with a system of grants tied to federal regulations and guidelines lay at the heart of the Clinton welfare reforms, the most important since the New Deal.

Coercive Federalism

In recent years some national actions have been described as coercive federalism, in which federal regulations are used to force states to change their policies to meet national goals. For example, until the 2012 Supreme Court decision involving the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA; commonly called Obamacare) struck down the provision, states were threatened with the loss of all Medicaid funding if they did not expand their Medicaid coverage to comply with the legislation.

More information

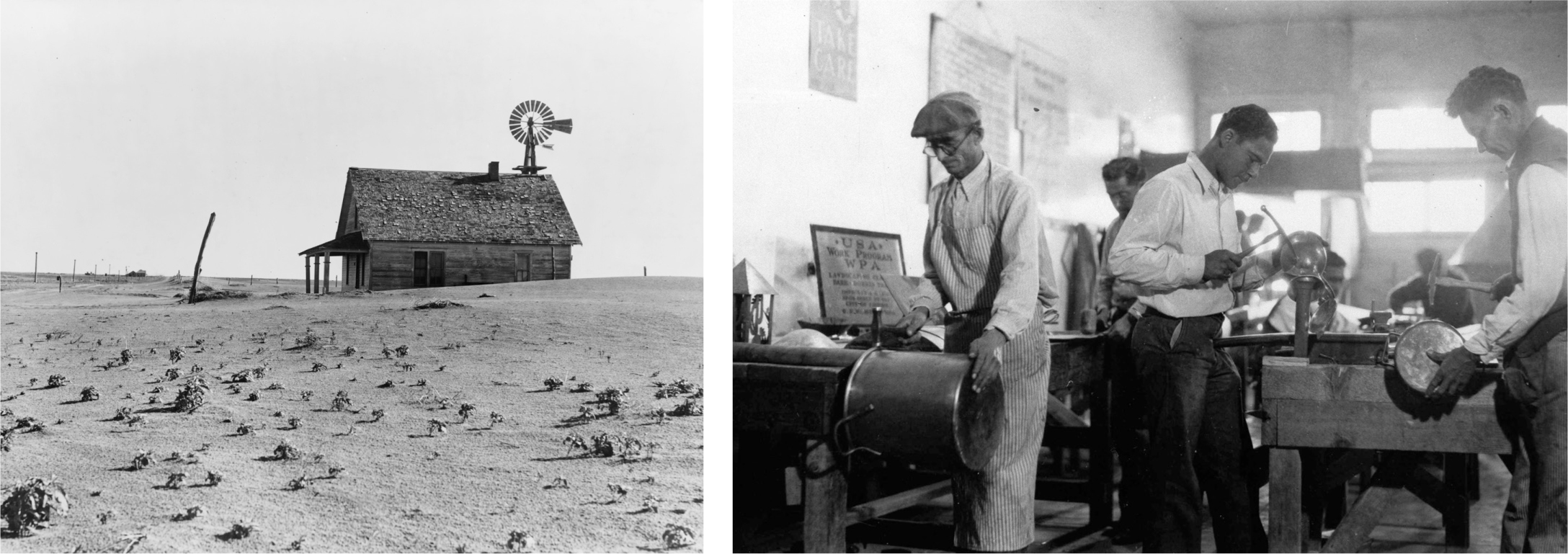

A black and white photograph shows a solitary cabin in a desert landscape.; A black and white photographs shows men working at machines to make copper utensils.

During the 1930s, Texans were affected by unemployment and drought that led to massive poverty across the state. The federal government stepped in to help, employing people in public works projects. Here, people make copper utensils for a Texas hospital.

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect of coercive federalism for states are federal unfunded mandates, which are federal laws or requirements that the state (or local) governments must implement, yet they receive no funding to offset the costs of compliance. For example, the federal Americans with Disabilities Act requires that street curbs be accessible to wheelchairs, but the federal government does not pay for the curbs. That cost is passed on to state and local governments and can place considerable financial strain on their tight budgets. The Congressional Budget Office reported that from 2007 through 2019 Congress passed 190 laws that imposed mandates on state and local governments. Federal laws imposing unfunded mandates upon state and local governments cover a wide range of issues, including child nutrition, driver’s licenses and identification cards, health care, and insurance, among others.33

Along with unfunded mandates, federal preemption is another aspect of coercive federalism. Preemption is based on the supremacy clause in Article VI of the U.S. Constitution, which states, “This Constitution and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; . . . shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” Preemption does not force expenditures upon the states, but it does prevent the states from acting in areas that the Constitution exclusively reserves to the national government. In 2008 the city of Farmers Branch, Texas, passed an ordinance that prohibited persons who were not citizens or legally in the United States from renting a residence inside the city. Violations of the ordinance were criminal offenses which applied to both the renter and the landlord. The federal Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down the ordinance on preemption grounds, holding that the law interfered with the national government’s constitutional power over immigration.34

TEXAS AND THE NATION

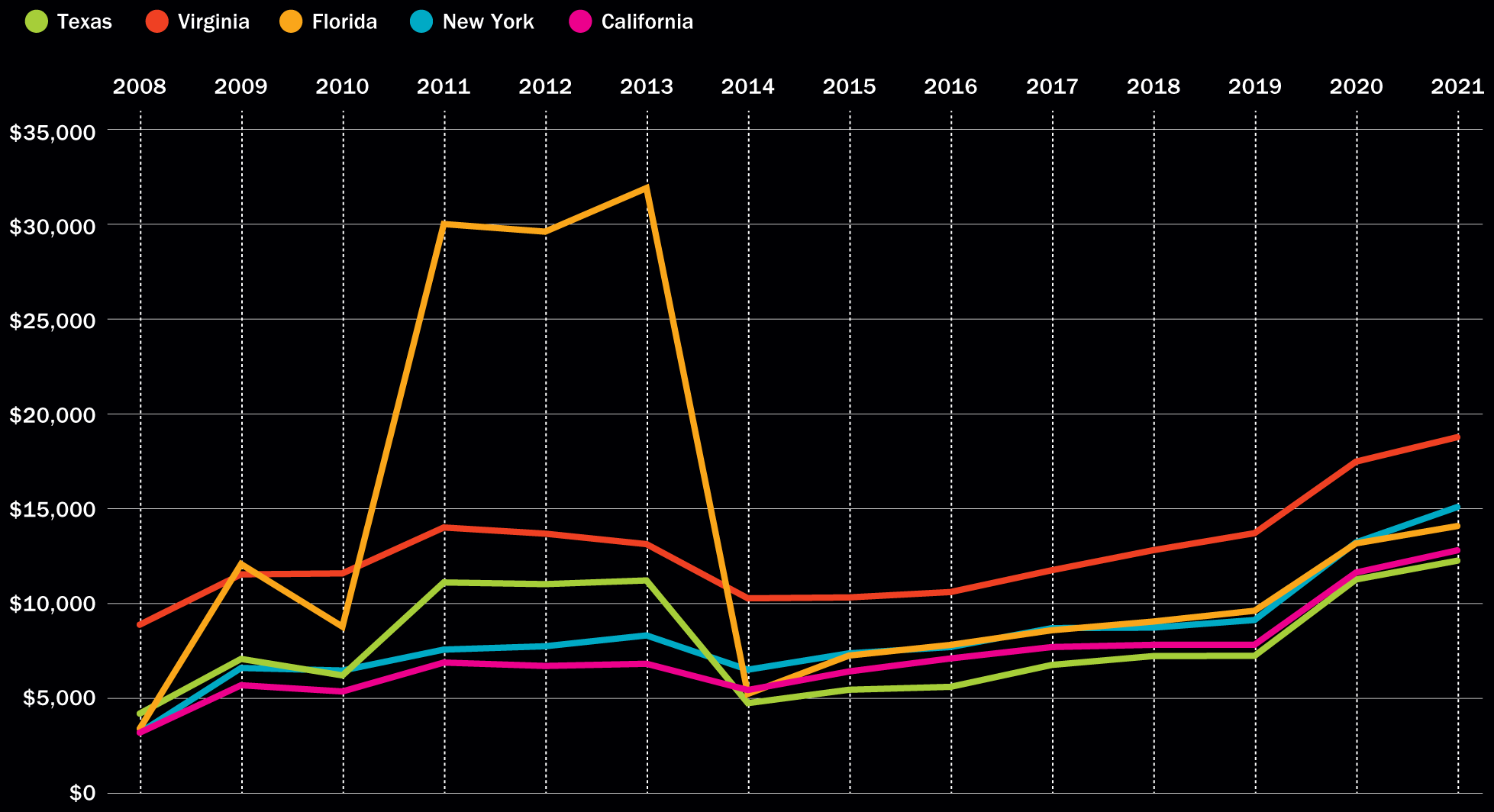

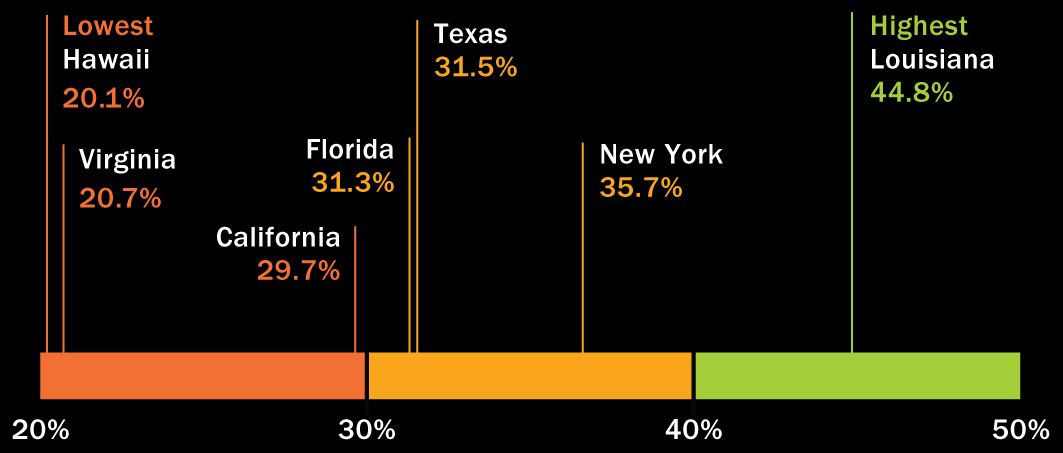

Federal Funds to Texas versus Other States

Many factors affect how much federal funding a state receives. Federal money can go directly to individuals, such as Social Security or Medicare. Federal money can also go to the states, which then decide how best to use the funds to benefit their constituents, such as for highway funding. In the graph below, we can see how much federal money Texas and Texans receive compared to other select states.

Federal Funds per Capita Received by States, 2008–21

More information

A graph shows the Federal Funds per Capita received by states from 2008 to 2021. There are lines for Texas, Virginia, Florida, New York, and California. Virginia starts near 9,000 dollars in 2008 and the other states start near 4,000 dollars. The states generally follow the same trend and gradually increase with Virginia staying about 5,000 dollars above the other states. By 2021, Virginia is near 19,000 dollars and the other states are between 13,000 and 15,000 dollars. The exception to this pattern is in 2000, Florida jumps to around 12,000 dollars which is the same as Virginia. It jumps again in 2011 to 30,000 dollars and stays high until 2014 when it returns to 5,000 dollars.

Federal Funding as a Percentage of State Revenue, 2019

More information

A graphic shows Federal Funding as a percentage of state revenue in 2019. The lowest state is Hawaii at 20.1 percent. Virginia is at 20.7 percent. California is a 29.7 percent. Florida is at 31.3 percent, Texas is a 31.5 percent. New York is at 35.7 percent. Louisiana is the highest at 44.8 percent.

SOURCES: “U.S. State Spending Profiles, 2008–2021,” www.usaspending.gov/state; calculated by author using U.S. Census State and Local Government Finance Historical Datasets and Tables, 2019, www.census.gov/data/datasets/2019/econ/local/public-use-datasets.html.

Video: Federal Funds to Texas versus Other States

CRITICAL THINKING

- How has the federal funding Texas has received changed over time, and how does it compare to the funding of other states?

- Federal grants account for nearly a third of state revenue on average, though there is considerable state-level variation. What could explain this variation across the states? In more recent years, how might the coronavirus pandemic have altered states’ revenue and the federal government’s share of total revenue?

★ CITIZEN’S GUIDE

Multistate Legal Challenges to Federal Policies

1. Why multistate lawsuits against the federal government matter

From taking on Big Tobacco in the 1990s to recent actions against pharmaceutical companies for their role in the opioid crisis, state attorneys general (AGs) have collaborated on litigation for decades. AGs have won large settlements from industries while also pushing for regulatory changes. Over time, the collaborative endeavors of AGs have become much more partisan, especially when directed at the federal government. AGs have used their positions to ally with like-minded partisans and advocacy groups to pursue ideological goals.a With the growing strength of partisan organizations like the Republican Attorneys General Association and Democratic Attorneys General Association, AG-led multistate lawsuits against the federal government have afforded state AGs a new way to shape national policy.

The issues raised through multistate lawsuits have an important impact on the lives of citizens. For instance, 22 Democratic AGs, led by Massachusetts AG Maura Healey, sued the Education Department and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos in 2017 over her decision to rescind the Borrower Defense Rule finalized during the Obama administration. This rule would allow borrowers to have their student loans canceled if their colleges made false claims to get them to enroll. The rule was established following the collapse of Corinthian College, a national for-profit chain, which left former students in heavy debt without a degree and with limited prospects of finding a good-paying job to pay back their loans. The Education Department under DeVos delayed the rule without soliciting, receiving, or responding to any comment from any stakeholder or the public and then unilaterally decided to change the rules to require that students prove not only that they were misled by their schools, but also that their school did it knowingly, making it more difficult for borrowers to receive financial relief. A federal court ordered the reinstatement of the Borrower Defense Rule. This decision led the Education Department to restart its processing of the claims and the financial relief.

The Texas attorney general also has a long history of suing the federal government, especially Democratic administrations. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton was the first to sue President Biden, filing the lawsuit two days after his inauguration. Paxton has found kindred spirits among other Republican AGs who have joined his pursuits by filing multistate lawsuits to thwart the Biden agenda. In March 2021, Paxton and Montana AG Austin Knudsen led a group of 19 other Republican AGs in suing the Biden administration over halting the Keystone XL pipeline project. Paxton, along with Missouri AG Eric Schmitt, sued Biden for reversing the Trump era “remain in Mexico” policy for asylum-seeking refugees and for halting construction on the U.S.–Mexico border wall.

2. What is the debate?

Those in favor of AGs using multistate litigation to challenge federal policies emphasize their important role in preserving liberty and checking federal power. The lawsuits can provide meaningful oversight of congressional and presidential actions, as well as oversight of administrative agencies, which set important rules yet lack direct political accountability. As the student lending example above demonstrates, unelected officials across federal agencies make decisions that can have profound influence over the lives of citizens. According to attorney Philip Green, multistate litigation provides a crucial check “[b]y allowing democratically elected state actors to collaborate and exert influence over national policy through litigation, constituents can now frequently hold undemocratic institutions politically accountable.”b

Critics say the lawsuits come at a high cost to taxpayers and have a low success rate. Additionally, they argue that the lawsuits are often driven more by partisanship than to protect liberty. The Texas AG was most active in filing lawsuits against the Obama administration. However, because Paxton failed to join lawsuits his colleagues in other states filed against the Trump administration, critics argue that the objective of the lawsuits is more about partisan politics than about representing the interests of the public.

3. What do the numbers say?

Since the 2000s, state AGs have been active in filing multistate lawsuits challenging policies and administrative rules. During the Clinton presidency, there were 42 multistate AG-led lawsuits filed against the federal government. The number skyrocketed to 157 multistate lawsuits filed by Democratic AGs against the Trump administration from 2017 to 2020. As of September 2022, the Biden administration had 54 multistate lawsuits filed against it.

While multistate lawsuits have increased overall, since 2004, bipartisan multistate litigation efforts have declined. From 1989 to 2000, Republican and Democratic AGs would routinely collaborate and file joint lawsuits challenging the federal government. Since then, a greater level of partisanship has emerged. State AG-led multistate lawsuits showed the most pronounced partisan patterns during the Trump presidency, in which 126 Democratic AG-led multistate lawsuits were filed, 4 of the 6 Republican AG-led lawsuits were challenging Obama-era policies still in effect, and there were no bipartisan multistate lawsuits. Of the 54 lawsuits filed against the Biden administration, the majority of those lawsuits (49) were led by Republican attorneys general, and only three were bipartisan.

Multistate Lawsuits by Attorneys General vs. Federal Government

State Attorneys General Litigation Against the Federal Government

*NOTE: All five Democratic AG-led lawsuits versus the Biden administration challenged Trump-era regulations. Four of the Republican AG-led lawsuits versus the Trump administration challenged Obama-era regulations.

COMMUNICATING EFFECTIVELY

What Do You Think?

- Have state attorneys general become too driven by partisanship at the expense of the public good? Why or why not?

- Are there particular policies on which you believe it is especially important for states to challenge the federal government? Are these issues unique to Texas, or do you believe states should work together to challenge the federal government on these issues? Explain.

Want To Learn More?

There are several websites that provide further information on state attorneys general and multistate litigation. For more information, visit the following websites.

- National Association of Attorneys General www.naag.org.

- Democratic Attorneys General Association https://dems.ag.

- Republican Attorneys General Association https://republicanags.com.

- State Litigation and AG Activity Database by Paul Nolette https://attorneysgeneral.org.

Fractious Federalism: Federal-State Relations under Party Polarization

Since 2000 a new form of federalism has emerged, one imbued with intense political partisanship. Fractious federalism has developed in response to the growing partisan polarization that characterizes contemporary American politics. According to political scientists Frank Thompson and Michael Gusmano, fractious federalism is defined by: (1) intense opposition to a federal policy or law that is rooted in state policy makers’ partisan, ideological identities; (2) active efforts of these state partisans to repeal or weaken the law either through court action and intergovernmental lobbying; and (3) reluctance by state policy makers to implement the federal policy or law.35 In other words, today’s heightened partisan environment shapes intergovernmental relationships. Conflicts between state and federal government officials don’t reflect a consistent belief about the proper amount of power the federal government or the states should have, but instead reflect conflicts between the parties, with state Republicans challenging laws enacted by Democrats at the national level and state Democrats challenging laws enacted by national-level Republicans.

As the parties have polarized on a variety of issues—from health care and gun control to immigration and environmental regulations—cooperation between national and state policy makers to solve problems and implement policies is shaped by partisan identities. Party loyalty heavily weighs into their decision making, with state leaders often deferring to national leaders of the same party and obstructing national leaders of the other party. State leaders who wish to obstruct the policies of national leaders of the opposing party have the capability to block and disrupt implementation of the policy at the state level, challenge the constitutionality of the policy, or pass their own policies that may undermine the national policies.

Traditional strategies employed by Congress and the president involving financial incentives have proven less effective when state policy makers have discretion and are partisan opponents of the national policy makers, and when cooperation with the national policy may be politically and electorally costly to state policy makers. Partisan considerations often drive decision making and overshadow more pragmatic considerations.36 For example, numerous Republican leaders across states, including those in Texas, were critical of the Affordable Care Act and refused to initiate the state health insurance exchanges intended under the act or expand Medicaid. They failed to implement these key provisions of the ACA despite financial incentives from the federal government to do so.

On immigration, the parties have been polarizing, and this has created opportunities for both cooperation and conflict between the national and state governments. Texas has been one of the most active states challenging the immigration policies of the Obama and Biden administrations. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton successfully led a group of 26 states in challenging President Obama’s Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) program, which would have protected about 4 million undocumented immigrants from deportation. In 2018, Paxton led a group of six states in challenging the Obama-era Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. In July 2021 a federal judge ordered the government to stop granting new DACA applications. Democratic attorneys general filed an unprecedented number of lawsuits against the Trump administration policies, including nineteen multistate lawsuits involving immigration.37 These lawsuits included challenges to President Trump’s Muslim ban, rescission of DACA, family border separations, and the border wall construction.

WHO ARE TEXANS?

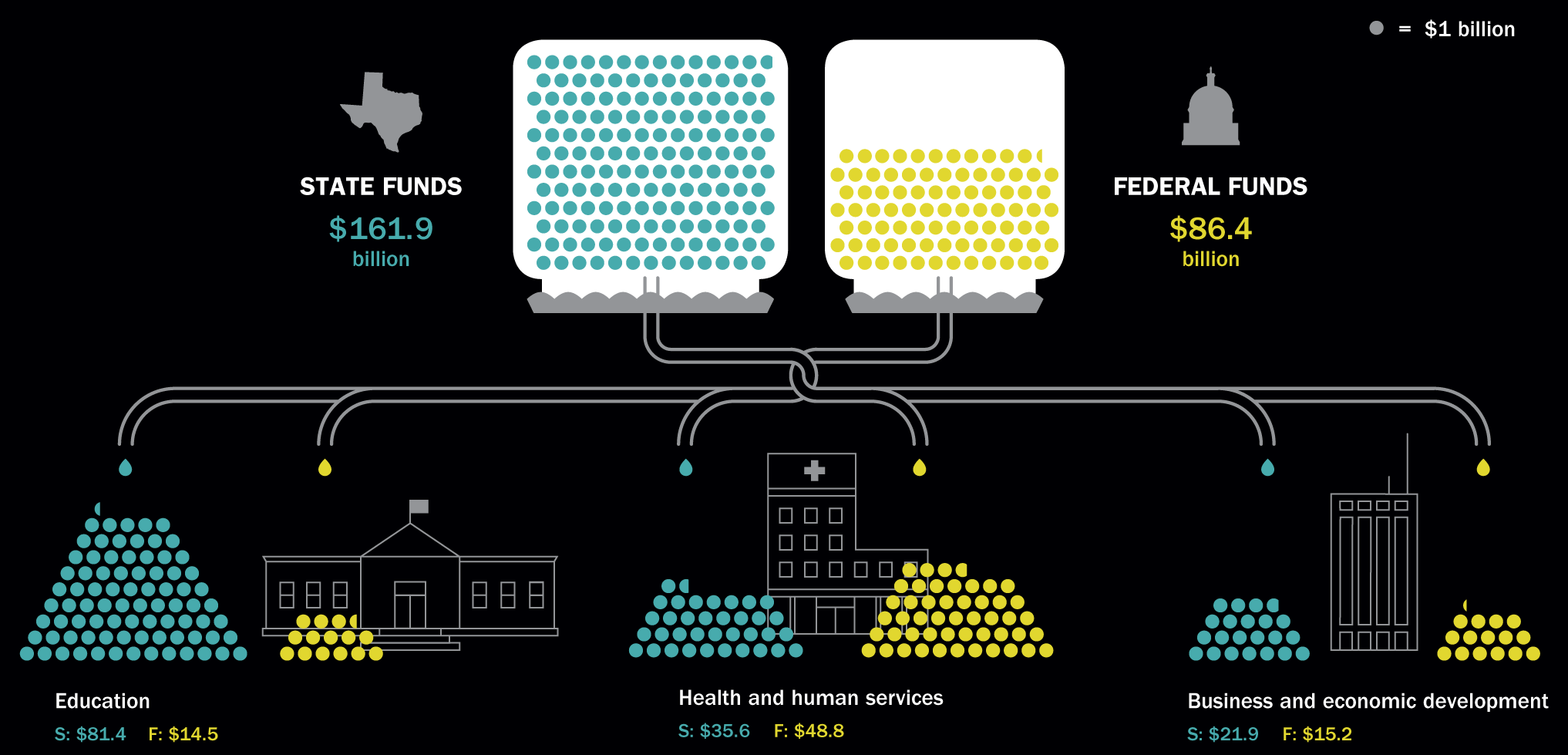

How Do Federal Funds Flow to Texas?

Federal grants provide states with money for programs that range from Medicaid and school lunches to tuberculosis control and immunization programs. As the chart below indicates, federal grants make up a majority of the money the state of Texas spends on health care and natural resources and a large share of the money spent on business and economic development.

2020–21 Texas Budget

More information

A Who are Texans infographic titled How Do Federal Funds Flow to Texas? Text reads: Federal grants provide states with money for programs that range from Medicaid and school lunches to tuberculosis control and immunization programs. As the chart below indicates, federal grants make up a majority of the money the state of Texas spends on health care and natural resources and a large share of the money spent on business and economic development. A graphic outlines the 2020 to 2021 Texas Budget. There was 161.9 billion in state funds and 86.4 billion in federal funds. This money is shown as divided into seven categories. Education received 81.4 billion state dollars and 14.5 billion federal dollars. Health and human services received 35.6 billion state dollars and 48.8 billion federal dollars. Business and economic development received 21.9 billion state dollars and 15.2 billion federal dollars. Public safety and criminal justice received 12.3 billion state dollars and 0.3 billion federal dollars. General government received 6.1 billion state dollars and 1.4 billion federal dollars. Natural resources received 2.1 billion state dollars and 6.3 billion federal dollars. Other such as regulatory, judiciary, legislature, and general provisions received 2.0 billion state dollars and 0.01 billion federal dollars. Quantitative reasoning questions ask: According to the data, what proportion of the Texas budget consists of federal funds? How might the presence of this federal money affect the relationship between the state and federal governments? Suppose federal funds for health and human services were eliminated. How might Texas reallocate state funds to avoid drastically reducing these services? SOURCE: Legislative Budget Board, “Fiscal Size-Up 2020–21,” pp. 2, 6.

More information

A graphic outlines the 2020 to 2021 Texas Budget. There was 161.9 billion in state funds and 86.4 billion in federal funds. This money is shown as divided into seven categories. Education received 81.4 billion state dollars and 14.5 billion federal dollars. Health and human services received 35.6 billion state dollars and 48.8 billion federal dollars. Business and economic development received 21.9 billion state dollars and 15.2 billion federal dollars. Public safety and criminal justice received 12.3 billion state dollars and 0.3 billion federal dollars. General government received 6.1 billion state dollars and 1.4 billion federal dollars. Natural resources received 2.1 billion state dollars and 6.3 billion federal dollars. Other such as regulatory, judiciary, legislature, and general provisions received 2.0 billion state dollars and 0.01 billion federal dollars. ? SOURCE: Legislative Budget Board, “Fiscal Size-Up 2020–21,” pp. 2, 6.

SOURCE: Legislative Budget Board, “Fiscal Size-Up 2020–21,” pp. 2, 6.

Video: How Do Federal Funds Flow to Texas?

QUANTITATIVE REASONING

- According to the data, what proportion of the Texas budget consists of federal funds? How might the presence of this federal money affect the relationship between the state and federal governments?

- Suppose federal funds for health and human services were eliminated. How might Texas reallocate state funds to avoid drastically reducing these services?

Independent State Grounds

States have leeway to expand rights of their residents through a concept known as independent state grounds. State constitutions can provide greater constitutional guarantees to a state’s citizens than the U.S. Constitution. Independent state grounds are a characteristic of federalism in that states are free to add to the rights guaranteed at the national level.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) legalized same-sex marriage throughout the United States, some states, such as Massachusetts, relied on their state constitutions to invalidate laws against same-sex marriage.38 Under the U.S. Constitution, Texas’s very inequitable property tax–based system for funding public education was held to be constitutional. In 1973 the U.S. Supreme Court held that education was not a fundamental right and so Texas only needed a rational justification—that is, local control of schools—for the funding system to be upheld.39 However, in Edgewood v. Kirby (1989), the Texas Supreme Court relied on the Texas Constitution to strike down the system on the grounds that it did not provide “what the [Texas] constitution commands—i.e., an efficient system of public free schools throughout the state.”40

In the 1970s there was a major effort to gain ratification of an Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. If ratified, the key part of the amendment would have stated, “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” Although the amendment was not ratified nationally, in 1972, Texas adopted its own version of the Equal Rights Amendment, which is Article 1, Section 3a, of the Texas Constitution: “Equality under the law shall not be denied or abridged because of sex, race, color, creed, or national origin.” U.S. Supreme Court decisions have provided major protection against sex discrimination under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; however, it is the Texas Constitution, rather than the U.S. Constitution, that contains an explicit ban.

Endnotes

- Paul Nolette, Federalism on Trial: State Attorneys General and National Policymaking in Contemporary America (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2015).Return to reference a

- Philip Green, “Keeping them Honest: How State Attorneys General Use Multistate Litigation to Exert Meaningful Oversight Over Administrative Agencies in the Trump Era,” Administrative Law Review 71 no. 1 (2019): 251–275.Return to reference b

- Morton Grodzins, The American System: A New View of Government in the United States, ed. Daniel J. Elazar (Chicago: Rand McNally, 1966).Return to reference 30

- Equal Justice Initiative, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror,” 2017, https://lynchinginamerica.eji.org/report/.Return to reference 31

- Gamble v. United States 587 U.S. (2019).Return to reference 32

- Congressional Budget Office. CBO’s Activities Under the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act.Return to reference 33

- Villas at Parkside Partners v. City of Farmers Branch, Texas, 726 F.3d 524 (2013).Return to reference 34

- Frank J. Thompson and Michael K. Gusmano, “The Administrative Presidency and Fractious Federalism: The Case of Obamacare,” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 44 no. 3 (2014): 426–450.Return to reference 35

- Timothy J. Conlan and Paul L. Posner, “American Federalism in an Era of Partisan Polarization: The Intergovernmental Paradox of Obama’s ‘New Nationalism,’ ” Publius: The Journal of Federalism 46 no. 3 (2016): 281–307.Return to reference 36

- Paul Nolette, State Litigation and AG Activity Database, 2021, https://attorneysgeneral.org.Return to reference 37

- Jill D. Weinberg, “Remaking Lawrence,” 98 Virginia Law Review in Brief 61, 66 (2012).Return to reference 38

- San Antonio v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973).Return to reference 39

- Edgewood Independent School District v. Kirby, 777 S.W.2d 391, 398 (Texas, 1989).Return to reference 40

Glossary

- dual federalism

- a form of federalism in which the powers and responsibilities of the state and national governments are separate and distinct

- layer-cake federalism

- a form of federalism in which the powers and responsibilities of the state and national governments are separate and distinct

- dual sovereignty

- the principle that states and national government have the power to pass laws and, in the case of overlapping laws, both the state and national government can enforce their laws

- police power

- the power of states to pass laws to promote health, safety, and public welfare

- cooperative federalism

- a way of describing federalism where the boundaries between the national government and state governments have become blurred

- marble-cake federalism

- a way of describing federalism where the boundaries between the national government and state governments have become blurred

- categorical grants

- congressionally appropriated grants to states and localities on the condition that expenditures be limited to a problem or group specified by law

- New Federalism

- the attempts by Presidents Nixon and Reagan to return power to the states through block grants

- block grants

- federal grants that allow states considerable discretion on how funds are spent

- coercive federalism

- federal policies that force states to change their policies to achieve national goals

- unfunded mandates

- federal requirements that states or local governments pay the costs of federal policies

- preemption

- an aspect of constitutional reasoning granting exclusive powers to act in a particular area to the national government

- fractious federalism

- a form of federalism in which partisan identity influences state officials’ cooperation with national policy

- Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA)

- an administrative decision of the Obama administration to help certain undocumented immigrants who have lived in the U.S. since 2010 and have children that are either American citizens or lawful permanent residents avoid immediate removal

- Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)

- an administrative decision of the Obama administration that certain undocumented immigrants brought to the U.S. as children would not be deported

- independent state grounds

- a constitutional concept allowing states, usually under the state constitution, to expand rights beyond those provided by the U.S. Constitution

SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY

Get Involved