Uruk

Urbanization in the Uruk Period, c. 3800–3100 BCE

The first West Asian cities emerged in the silt-rich plains of southern Mesopotamia, in the area that stretches roughly from present-day Baghdad to the Persian Gulf. Over the course of the Uruk period (c. 3800–3100 BCE), once-dispersed small communities gradually gathered around a series of economic, ceremonial, and ritual centers, forming two of the earliest-known cities, both in modern Iraq: Uruk (on the site of modern Warka) and Nippur. Food for the residents of these cities was produced in adjoining fields and farms, which freed some of the community to specialize in crafts, to work in administrative capacities for the temples and elite class, and to engage in trade and mercantilism.

The material culture of Uruk tells the story of early urban development. For example, the highly specialized and individually decorated ceramics of earlier cultures were replaced by mass-produced, utilitarian coarseware known as beveled rim bowls, suggesting that production had to keep up with a significant surge in the population. By the late fourth millennium BCE (the last few centuries before 3000 BCE), Uruk encompassed over three-quarters of a square mile, and its legendary city wall was constructed. The rulers and the wall of Uruk are mentioned in later Mesopotamian epic poetry, such as the Gilgamesh Epic, which celebrates the feats of Gilgamesh, legendary king of Uruk.

Eanna

Inanna

Both the invention of writing and the first monumental arts of this period emerged in the temple, the space of religious and ceremonial practice. In the early Mesopotamian city, temples were the first urban institutions. Dedicated to both female and male gods, temples housed daily rituals, worship of multiple deities, and occasional festivals. The gods were believed to dwell above the heights of mountains or deep in the underworld, but they also resided in the temples that people made for them, and thus served as the patrons of those cities. The temple priests and priestesses made sure that daily rituals were maintained with appropriate sacrifices and offerings so that the divinities were pleased and the order of the city was maintained. This role in appeasing the gods gave temples enormous power, but they were more than religious places: they organized agricultural production, owned large flocks, and employed craftspeople and merchants. Because of their economic power, temples were also sites of politics and royal sponsorship. Uruk had two such urban institutions: Kullaba (the Temple Precinct of Anu) and Eanna (the Temple Precinct of Innana). They were dedicated to the two chief deities of the city at the time: Anu, the god of heavens, and Inanna, the goddess of agricultural prosperity, abundance, and sexuality.

The development of writing in southern Mesopotamia coincides with the emergence of cities, and therefore was part and parcel of a highly innovative time. Since the earliest texts we have from Uruk are lists of commodities, archaeologists and historians have pointed out the economic role of writing as primarily a technology of exchange. Such long-distance trade was important to the economy and social organization of these early cities, since the region lacked some of the most crucial natural resources, such as building stone or quality timber for construction, precious stones for seals, jewelry, or statuary, or any metals for tools and weaponry. Approximately six thousand tablets were excavated from the Eanna Precinct at Uruk, which suggests that once invented, writing was widely adopted in Mesopotamia (see box: Making It Real: Writing in Mesopotamia).

Ziggurat

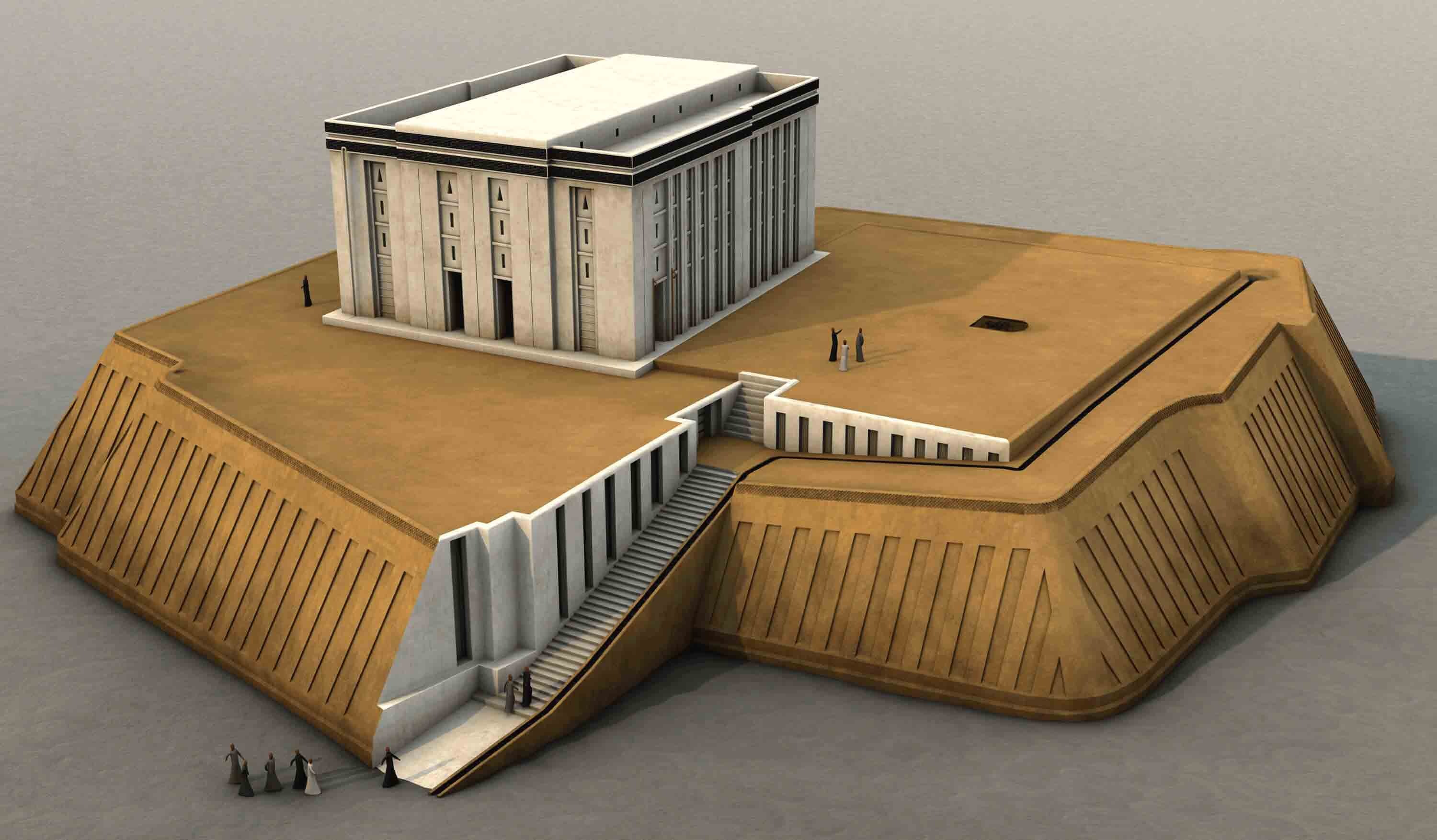

THE TEMPLE OF ANU AT URUK Around 3300 BCE, the Temple of Anu (Fig. 3.2) in the Kullaba precinct was built on a tall earthen platform, allowing the temple to rise high above Uruk’s urban center, and, impressively, be visible for miles. The platform was built over previous levels of temple construction and was elaborately decorated with niches all around. It hints at an early example of a ziggurat, a type of temple built during the later periods of Mesopotamian architecture (see Fig. 3.19).

More information

The rectangular temple, four or five stories high, has columnar window niches and two courtyards on the roof. The temple sits atop an earthen platform with sloping sides also decorated with niche-like cutouts. Stairs and a curved ramp lead from the base of the platform up to the temple.

facade

Constructed of mud bricks, the exterior walls of the Temple of Anu were plastered with white gypsum, giving it its modern name: the White Temple. It had a deeply niched facade, which created alternating light and shadow under the intense sun of southern Iraq, as well as niched surfaces in its central ritual space. The building consisted of a central, oblong ceremonial space with smaller rooms on either side. By adapting the three-room design of domestic houses for the dwellings of gods and goddesses, the builders of the Temple of Anu monumentalized house design by elevating it to the realm of the gods.

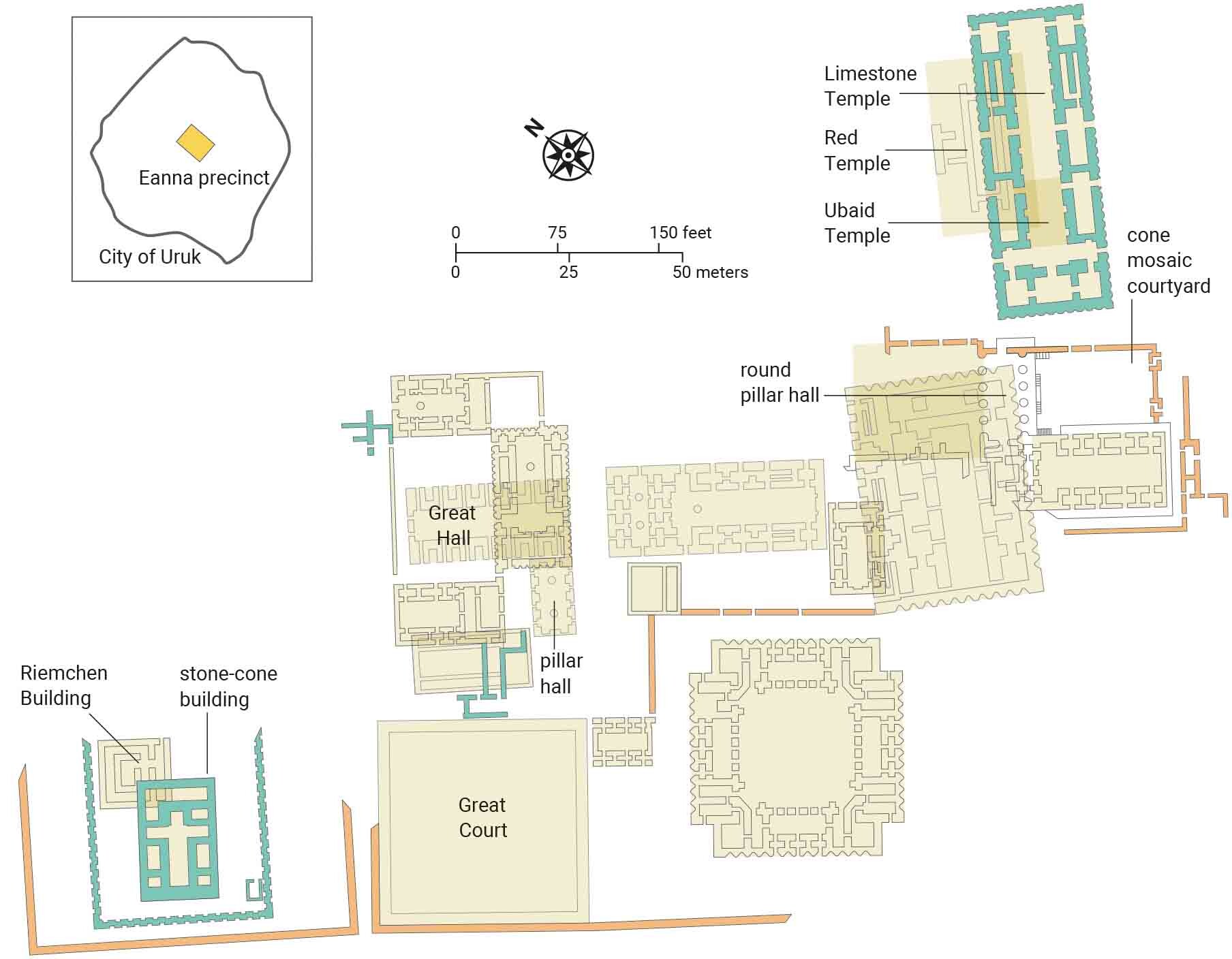

THE EANNA TEMPLE PRECINCT The architecture of the group of buildings in the Eanna (“House of Heaven”) precinct was even more complex and extensive than the Temple of Anu in the Kullaba precinct. The overlapping buildings on the site’s architectural plan (Fig. 3.3) indicate that the Eanna precinct underwent a series of construction projects in the last few centuries of the fourth millennium BCE (roughly 3300–3000 BCE).

Parthenon

The precinct consisted of multiple structures, including temples dedicated to the goddess Inanna, storerooms, and administrative buildings. Many of the buildings shared the deeply niched facade design of the Temple of Anu. The Riemchen Building, a rectangular building excavated in the Eanna Complex, yielded a particularly rich trove of artifacts, probably dedicated to Inanna’s temple. The Limestone Temple (top right in Fig. 3.3) was a massive structure, measuring 250 × 98 feet (76.2 × 29.87 m)—larger than the Parthenon in Athens (see Fig. 14.3), which would not be built until more than 2,500 years later. Its foundations were built of finely cut blocks of limestone, transported from a long distance and laid in precise rows or courses. This ashlar technique was later abandoned, probably because the southern Mesopotamian plain did not have enough stone to build many such structures, making the technique unsustainable in the long term. Nevertheless, this period of innovative design is significant because it questioned older traditions and sought new forms and methods.

More information

The complex is roughly 1000 feet long, corner to corner, and includes later structures built over the sites of earlier ones. One end of the complex is the site of a so-called ubaid temple, a much larger limestone temple, and the intermediate sized red temple. The other end of the complex is the site of the stone-cone building and the Riemchen building. The center of the complex includes the Great Hall, pillar hall, and round pillar hall. There is also a Great Court.

CONE MOSAICS Another innovation at the Eanna precinct was the use of cone mosaics to consolidate and decorate the mudbrick walls (Fig. 3.4). Cone-shaped pieces with a tapered, peg-like form were either fashioned from terra-cotta or carved from stone. The cones were then embedded into plaster to create a surface covering for walls and columns. This protected the mudbrick from the physical effects of rain, wind, and human use, giving it a longer life. Additionally, the painted tops or natural colors of these cones (usually red and black) allowed artists to create a mosaic-like surface decoration, bringing a playful vividness to the architecture. The designs, typically geometric, might have imitated the patterns found on reed mats and textiles used in houses. While the cone mosaics were an important innovative design in architectural technology in south-ern Mesopotamia in the Uruk period, they were later abandoned—proof that not all newly invented technologies or art forms become incorporated into long-term traditions.

More information

The mosaics cover the bases of columns beside a set of steps. The left mosaic has a bold horizontal zigzag pattern, the middle mosaic has a subtler pattern of small triangles, and the right mosaic has a bold pattern of repeating diamond shapes.

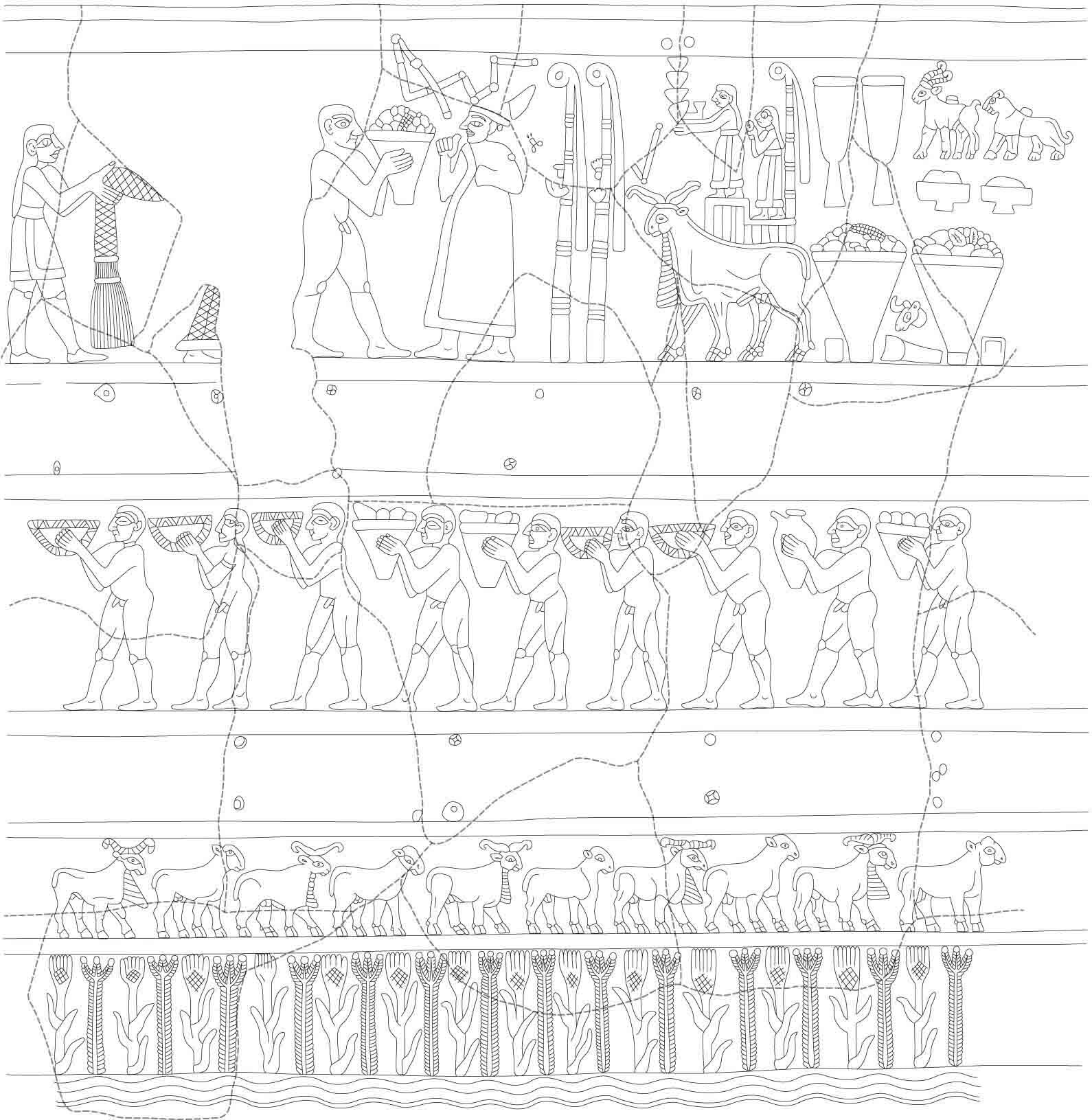

URUK VASE Serving as the center stage of urban economic activity, the temple and its divinities both produced and received food and livestock, fine art objects, and the first public monuments with political imagery in West Asia. Archaeologists working at Uruk’s temple precincts have discovered storerooms packed full not only of small precious artifacts but also of large monuments. This carved alabaster vase (Fig. 3.8), over 3 feet high, was found in a storeroom in the Eanna precinct. The vase appears to have been broken and repaired in antiquity, suggesting its significance and long life in the temple. It was further damaged when it was looted from the Iraq Museum in 2003 during the U.S. invasion, but it was returned and repaired a few months later.

More information

Three rows of carved relief decorations encircle the vase. The bottom row shows rams and goats above two alternating agricultural crops. The middle row shows naked men carrying bowls, baskets, and a large vessel. The top row shows a naked man offering a basket to a robed figure. This row also contains three animals, food containers, and other people. Two small figures appear to stand on the back of one of the animals.

More information

The drawing illustrates the vase’s three rows of carved relief decorations. The bottom row shows rams and goats above two alternating agricultural crops. The middle row shows naked men carrying bowls, baskets, and a large vessel. The top row shows a naked man offering a basket to a robed figure. This row also contains three animals, food containers, and other people. Two small figures appear to stand on the back of one of the animals.

The vase is one of the earliest examples of pictorial narrative, which represents a radical innovation within Mesopotamian art, toward storytelling in pictures. The carving on the surface of the vase is divided into several horizontal registers (Fig 3.8a). In the lowest register, wavy lines define the base of the composition as water, topped with an alternating row of flax plants and date palms, although the identification of these plants is debated. Just above the vegetation, alternating rams and ewes walk to the right. This three-level base shows an ordered ecology of water, plants, and animals, most likely associated with the worship of Inanna throughout Uruk’s marshy southern landscape. The vase’s middle register depicts a row of naked and clean-shaven males with defined genitalia. The men move to the left, carrying foodstuffs in baskets and vessels, perhaps a visual representation of the ritual offerings of food and drink to the gods and goddesses performed at this and other temples.

The alternating direction of movement on the vase from both left and right connects the moving bodies in the separate registers into a single procession that culminates in the top register with the presentation of offerings to a female figure, most probably the temple priestess, who wears a long robe and a headdress. A figure who seems to be overseeing the ceremony is unfortunately not preserved because of an ancient repair, but many scholars believe he was a king or similar person of importance. Just in front of where he stood, a naked male figure delivers an offering to the priestess. Behind her stands a pair of reed posts, which are a symbol of Inanna. Behind the posts, the temple compound is represented by various offerings, including the animals shown in the procession below and alabaster vases similar to the Uruk Vase itself.

stele

LION-HUNT STELE The urban complex of Uruk does not appear to have the type of buildings that could be called a palace—the residential and administrative buildings associated with a king. However, images of a bearded man wearing a kilt do appear in carvings and objects, and scholars believe this figure represents an individual with both religious and worldly power. In archaeological studies of Uruk, this figure is called a priest-king (known as En in later Sumerian texts) because he is often depicted as a dominating individual associated with acts related to the worship of Inanna. The Lion-Hunt Stele (Fig. 3.9), a roughly shaped, carved basalt boulder discovered in the Eanna precinct, includes carved representations of this distinctive human figure hunting lions. He appears twice in the scene, at two different scales: first with his spear (above) and then with his bow and arrow (below). He wears a long kilt and has a long beard and a bun-like hairstyle and headdress. The uneven, natural form of the boulder and the floating images on the smoothed surface suggest that this stele is an early example of a public monument, a medium for the expression of state ideologies in Mesopotamia.

More information

Below, a bearded figure in a skirt-like garment fires an arrow from a bow. Above, a similar figure wields a spear against a rearing lion.

VIDEO: The Met, 82nd & 5th: Sealed / Yelena Rakic (Cylinder seal)Show VideoHide Video

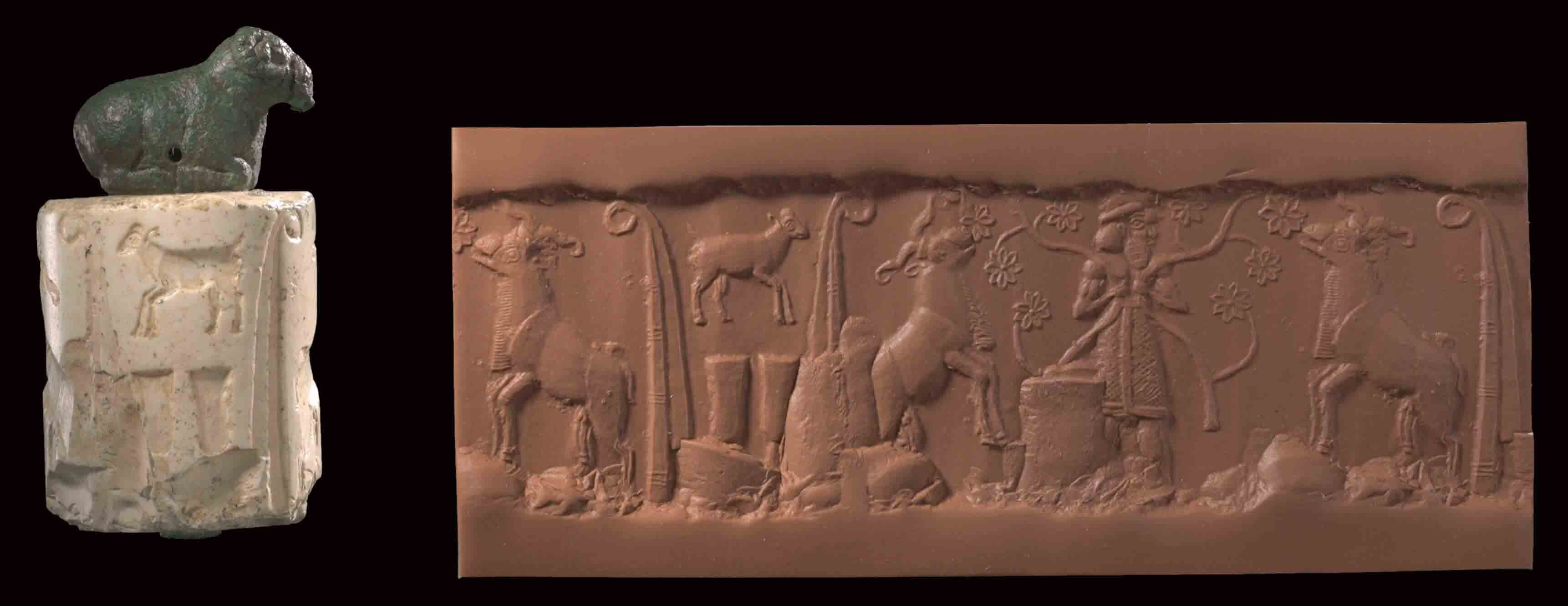

CYLINDER SEAL The priest-king is also depicted on many Uruk seals, including this cylinder seal found in the Eanna precinct, illustrated with its modern impression (Fig. 3.10). Seals functioned as bureaucratic tools for administering trade and exchange. Using metal tools, artisans carved distinctive designs, typically figures, into hard precious stones. When pressed against wet clay, the stamp seal left a raised impression that acted as the signature of a merchant, official, or other important person. Storeroom doors, vessels containing foodstuffs, and even clay envelopes for letters or contracts were sealed in this way. The cylinder seal was an innovation of the Uruk period. Instead of a flat surface, the design was carved onto a round stone, which could then be rolled across the wet clay. Because of the round design, the impression could be rolled over longer spaces, creating one continuous image.

VIDEO: The Met, The Artist Project: DUSTIN YELLIN on ancient Near Eastern cylinder sealsShow VideoHide Video

lapis lazuli

Gebel el-Arak

Many cylinder seals were carved from imported semiprecious stones, such as agate, hematite, or lapis lazuli—which was one of the most widely used precious stones in early Mesopotamian prestige objects. Lapis lazuli was mined in the Badakhshan Mountains of Afghanistan, indicating the Mesopotamians’ involvement in long-distance trade. These stones were believed to have symbolic meaning, adding an extra layer of importance to the seals. The seal shown here was carved from marble. Its impression features a rocky scene with animals, posts, and a male figure. The man appears to be the same Uruk priest-king seen on the Lion-Hunt Stele (Fig. 3.9). A similar figure is found on a knife carved in Egypt, known as the Gebel el-Arak knife (see Fig. 4.2). This shared iconography and the discovery in Egypt of cylinder seals that were clearly made in Mesopotamia demonstrate the existence of direct or indirect contact between these ancient cultures even at this early date.

More information

A modern clay impression created by the seal depicts a scene with three goat-like animals, a standing male figure, stones, vessels, two posts, and a flowering tree in the background.

Glossary

- coarseware

- a type of thick, gritty pottery used for everyday purposes.

- ziggurat

- a stepped pyramid or tower-like structure in a Mesopotamian temple complex.

- facade

- any exterior vertical face of a building, usually the front.

- course

- a layer of bricks or other building units arranged horizontally along a wall.

- ashlar

- a stone wall masonry technique using finely cut square blocks laid in precise rows, with or without mortar.

- terra-cotta

- baked clay; also known as earthenware.

- pictorial narrative

- storytelling in pictures that presents a connected sequence of events.

- mosaic

- a picture or pattern made from the arrangement of small colored pieces of hard material, such as stone, tile, or glass.

- register

- a horizontal section of a work, usually a clearly defined band or line.

- stele

- (plural steles) a carved stone slab that is placed upright and often includes commemorative imagery and/or inscriptions.

- iconography

- the visual images or symbols used by artists within their work to convey specific meanings.