Ur

Eshnunna

Ur

Eshnunna

In what is now called the Early Dynastic period in Southern Mesopotamia (2950–2350 BCE), several prosperous cities, with a new urban elite, emerged. The cities of Khafajah, Eshnunna, and Ur were the capitals of relatively small regional kingdoms that controlled farming and herding territories and their networks of irrigation. These autonomous urban communities depended on agricultural production and animal husbandry, and they continued long-distance trade with Anatolia, the Persian Gulf, and beyond. They also shared religious beliefs and practices involving the worship of Mesopotamian gods and celebration of their festivals. The artifacts found in graves show an increase in precious materials and prestige goods, indicating the growth of the urban elite class. These changes in social structure, and the growing centralization of power and wealth, created conditions for major architectural projects, as well as remarkable changes in the visual arts and burial practices under the sponsorship of the temple institutions and the new elite class.

VOTIVE FIGURES During the Early Dynastic period, temples remained the most important urban institution, and individuals and families continued to make offerings to the deities enshrined in them. Such gifts often took the form of carved stone plaques, metal objects, and votive statues. Placed in a cult room where rituals were held, votive statues allowed their donors to be in the presence of the divine. In return for these gifts, the donors expected the god or goddess to protect them from harm and bring them good fortune.

A remarkable treasure trove of votive statues comes from the Temple of Abu in Eshnunna (present-day Tell Asmar, Iraq). They were excavated in a cult room, where they had been buried in antiquity under the floor behind the altar. The statues were carved from veined gypsum—a soft stone—at a variety of scales, using abstract formalism: several of the bodies have conical shapes, cylindrical legs, and square sections (Fig. 3.11). The legs, many of which were shaped to be viewed only from the front, serve as pillars that carry the whole body. Each statue has a rectangular base to keep the figure standing upright.

Most of the male votives have long beards and hair, elaborately detailed with horizontal wave-like patterns, and most of the females have braided hair. The majority of the figures wear skirts that end with a row of tassels, while a few wear ceremonial sheepskin skirts delicately carved into the gypsum. Some of the women have one shoulder exposed. All of the votives share two distinctive features. First, their hands are clasped on their breasts in a pose of veneration, ready to hold libation cups for their ritual liquid offerings. Second, they have large inlaid eyes made of bright materials: shell for the cornea and black limestone or lapis lazuli for the iris. These eyes give the votives an intense gaze, which would have been fixed on the image of the deity in the temple. We do not know the social status of the individuals represented, but because the statues are not inscribed, we do know that they were not royal. The form of these votive statues was borrowed by later Mesopotamian kings who had similar statues carved from more precious and durable stones, such as diorite.

Nanna

ROYAL TOMBS OF UR One of the most prominent cities of the late third millennium BCE (the last few centuries before 2000 BCE) was Ur, the modern site of Tell el-Muqayyar in southern Iraq, home to an important sanctuary complex dedicated to the moon god, Nanna. Royal tombs excavated at Ur by archaeologists between 1922 and 1934 present evidence of elite power, long-distance trade, and artistic production.

While digging at the southwestern corner of Nanna’s temple, archaeologists found and excavated nearly two thousand burials in a massive and very deep burial ground that dated to long before the construction of Ur Namma’s temple complex, and, based on the architecture of the finds and the goods buried with the deceased, they identified sixteen royal tombs. In a few cases, including the tomb of Queen Puabi (Tomb 800), a retinue of individuals was ritually buried with the elite individual. Up to seventy-five people were buried simultaneously, wearing ritual garments and holding musical instruments or ceremonial objects. All members of the entourage held a small cup from which they may have drunk poison at the height of the ceremony, and some skulls show evidence that they died of blows to the head, suggesting human sacrifice. The wealth of artifacts within the royal tombs provide a rare window into urban life in the third millennium BCE, and demonstrate the complexity of technologies of production, the artistic skills, and the extent of long distance trade in Mesopotamia at the time.

ROYAL STANDARD OF UR One of the most intriguing finds in the burial ground is the Royal Standard of Ur, which was discovered in a man’s tomb, Tomb PG 779. The Royal Standard is a hollow wooden trapezoidal box, decorated on four sides with inlaid mosaic scenes made from shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli, and set in bitumen (a naturally occurring black viscous mixture that acts as a sort of glue or binder). Leonard Woolley, a British archaeologist who excavated at Ur, called this mysterious object a standard (a ceremonial banner) because he assumed that it would have been raised on a pole and perhaps used in funerary or other ritual processions, similar to the standards depicted on the Egyptian palette of Narmer (see Fig. 4.3). Scholars are now skeptical of Woolley’s interpretation, but other theories of the object’s original use have not been verified.

Whatever its function, the standard provides an early example of a pictorial narrative in which political conflict, war, and feasting are linked in a cause-and-effect relationship. Each of its two main faces depicts different episodes in a narrative divided into three horizontal registers, with concluding scenes on the top register. One face depicts a battle and the subsequent capture of prisoners of war, who are then presented to a person of high status (Fig. 3.12a). In the bottom register, chariots, each drawn by four onagers (a species of wild ass or horse), trample over the naked bodies of defeated enemies. The scene continues in the middle register with a group of armed soldiers taking their naked enemies prisoner. In the top register, the captives are presented to the centrally placed ruler. The use of hierarchical scale depicts him as slightly taller than the others, and his dominant position in the scene suggests his status as a leader. Accompanying him are courtiers holding instruments. The chariot at the far left is perhaps reserved for the ruler.

The standard’s other main face also depicts people moving across the three registers. On the top register, the narrative involves a celebration in the form of a banquet (Fig. 3.12b). One figure, slightly larger than the others, dominates the scene. He is seated, holding a cup and wearing the ceremonial flounced skirt that is common in representations of elite people in early Mesopotamian art (see Fig. 3.11, for example). He is facing the other banqueters, who are entertained by what appear to be a lyre player and a singer on the far right. The lower two registers illustrate long processions of people bringing animals and various goods, perhaps as tribute to their ruler. Interestingly, the lyre’s front is decorated with a bull’s head similar to that from the Great Lyre of Ur (Fig 3.13.)

GREAT LYRE OF UR Another spectacular find from the Royal Tombs of Ur is the Great Lyre (Fig. 3.13), found within a king’s tomb (Tomb 789) that was looted in antiquity. Lyres must have been popular musical instruments for the funeral ceremonies at Ur, because the Royal Tombs contained several of them. The wooden core of the lyre’s eleven-stringed soundbox has disintegrated, but the delicately inlaid and constructed front of the lyre was preserved. It was found adjacent to the bodies of elaborately dressed women who took part in the burial ceremony.

The front of the lyre has an inlaid base and is topped with a bearded bull’s head sheathed in gold. Below the bull’s head, four registers of narrative scenes are inlaid with shell on bitumen. These scenes depict animals engaged in activities normally associated with humans, such as butchering meat, carrying and pouring liquid from vessels, and playing musical instruments. In the top scene, a naked hero uses his arms to control two human-headed bulls who stare at the viewer. Taken together, the scenes seem to present either funerary rites or the afterlife in the underworld, but with animals taking on human roles.

Stele of Eannatum

Lagash

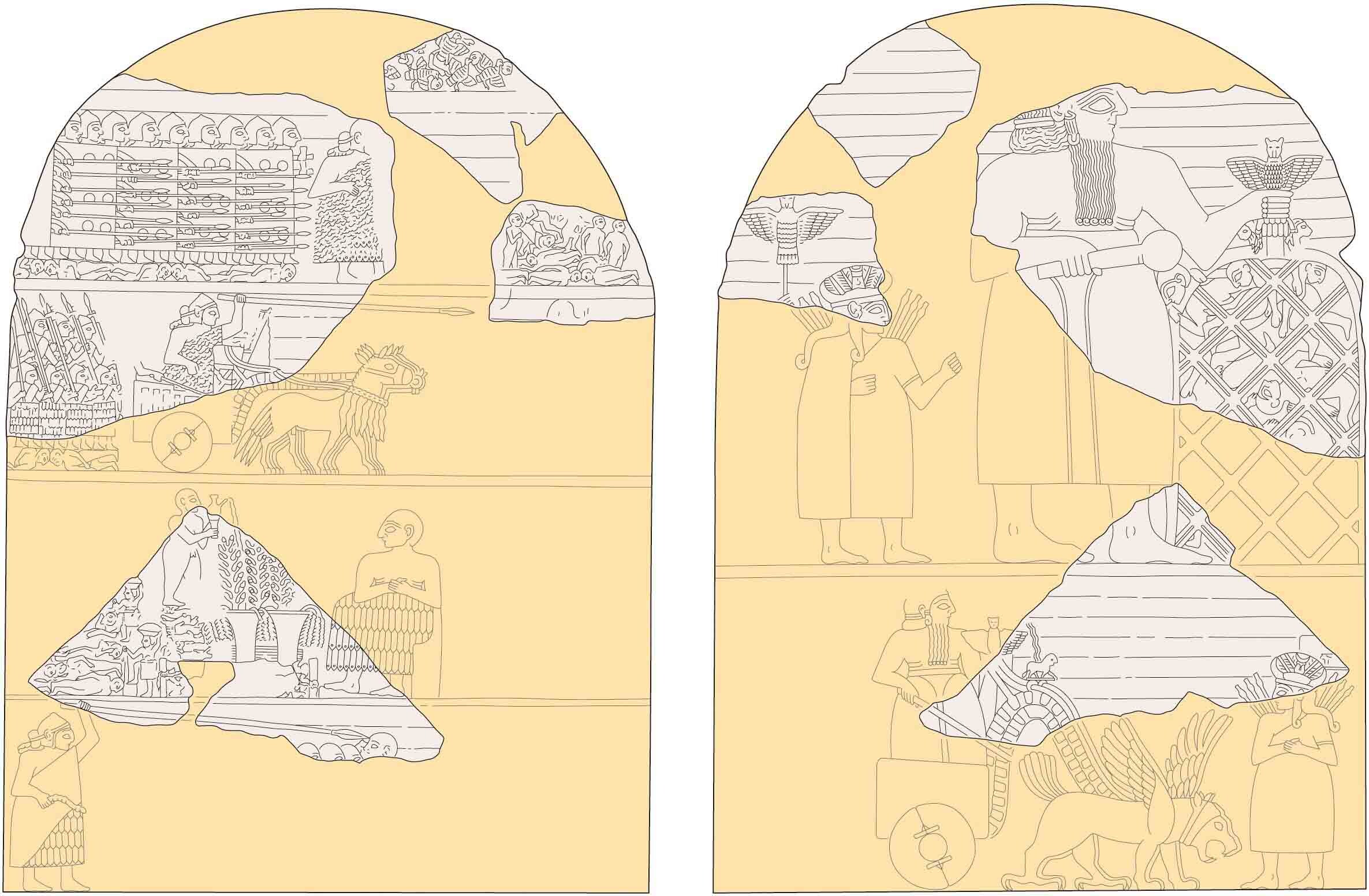

STELE OF EANNATUM As the power of the city-states of the Early Dynastic period grew and their people interacted through trade and through conflicts over water and land, public monuments were used as both written and visual statements of power and political sites. Public monuments commemorate specific events or people while also defining and shaping urban spaces through their visual and architectural force. One of the earliest examples of a public monument that combines the power of inscription with the force of visual narratives is the Stele of Eannatum from the kingdom of Lagash, in modern-day Iraq (Fig. 3.14). This limestone monument, dated to 2460 BCE, was an imposing round-topped stele of nearly 6 feet. Preserved only in several fragments, it is primarily a victory monument erected by the city-state of Lagash, which defeated the city-state of Umma in a dispute over agricultural territory that was sacred to the god Ningirsu, the storm god and patron god of Lagash. The monument was a legal contract that settled the land dispute and formalized the agreement by marking the agreed-upon border.

The visual composition tells the story of this important victory for Lagash from two different perspectives, one historical and the other mythological. On one side (the left in Fig. 3.14), the story of the battle is arranged in four registers. Art historians have suggested a bottom-to-top sequential reading of this narrative, culminating in the military victory of Lagash’s king, Eannatum, who appears in the top two registers and is recognizable by the ceremonial sheepskin he wears. In the second register from the top, he leads his army in a chariot. In the top register, he leads them on foot. The right side of the top register shows the violent and gruesome consequences of the war with a heap of naked and dead Umma soldiers, whose heads are picked up and carried away by vultures.

The reverse side depicts the mythological gathering considered to be the main agents of Lagash’s victory. The god Ningirsu holds the Umma soldiers in his mythical battle net (upper right) and keeps them in order with his ceremonial mace. He is accompanied by his mother, the Lady of the Mountain, and by the lion-headed eagle Anzu (upper left). The two sides of the Stele of Eannatum therefore commemorate Lagash’s defeat of Umma both as a historical event and as a mythologically inevitable outcome. The Sumerian text (not shown in the reconstructed drawing) is inscribed in the highly pictographic cuneiform script of the time and fills in the negative spaces of the images. This text tells the same story in a different way: King Eannatum decides to battle Umma and goes to the temple to receive divine instruction. There, in a dream, he is told that the corpses of his enemies will form a mound reaching the base of heaven. A section of the text is missing, but the last section of the inscription summarizes how Eannatum took up arms against Umma.