Kuba

Nyim

Mishe miShyaang maMbul

ndop

Art historians have used similar combinations of stylistic analysis and accounts by European visitors to relate the treasures of Central African kingdoms to oral traditions. In the vast equatorial regions that stretch from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Rift Valley, ruling clans once honored their founding heroes and heroines by sculpting their idealized images or by impersonating them in masquerades.

Kuba

Nyim

Mishe miShyaang maMbul

ndop

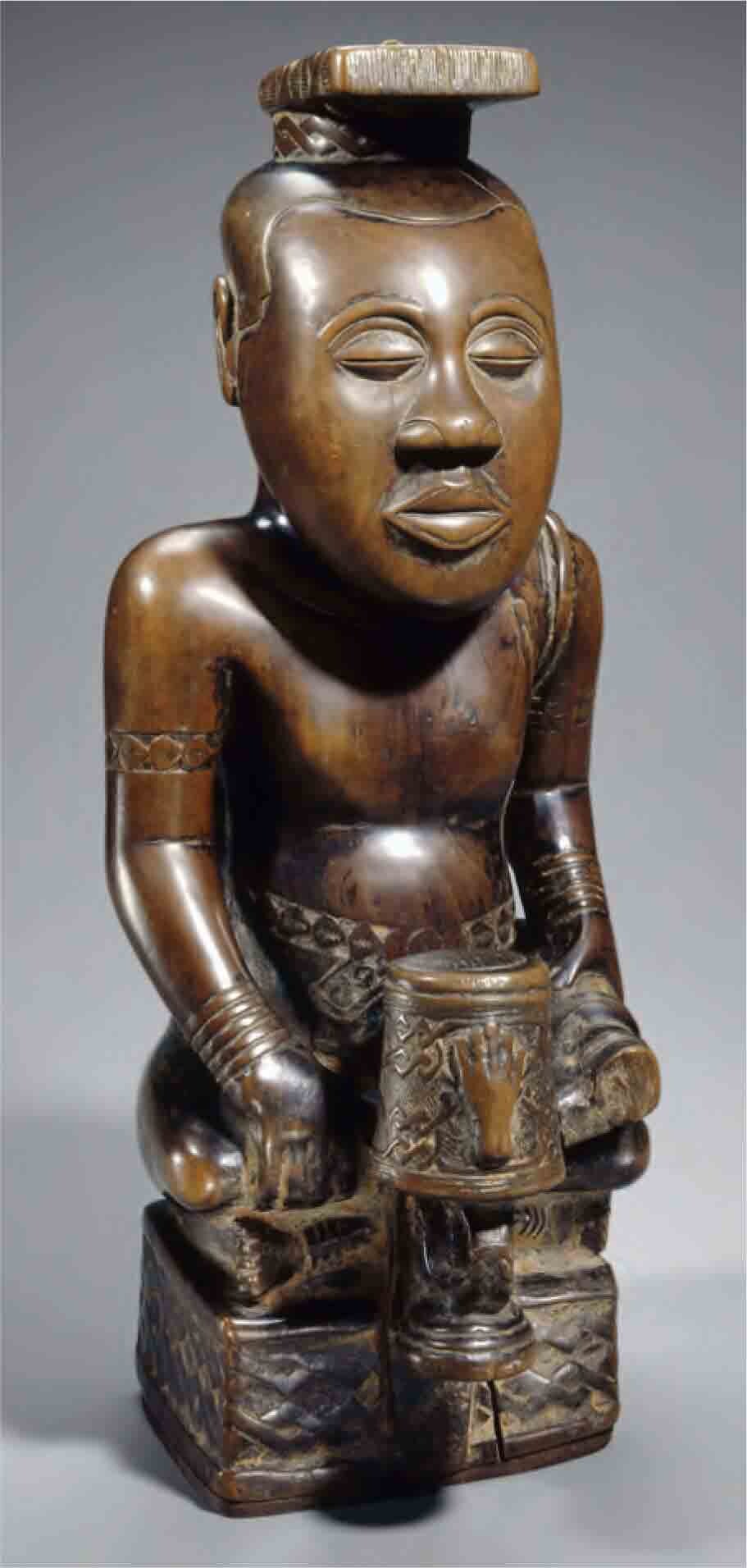

KUBA ROYAL STATUE For generations, blessing and protection were provided by wooden statues of the rulers belonging to the Bushong clan of the Kuba, whose oral histories document a dynasty of more than one hundred kings. The oldest of such figures (Fig. 49.12) seems to honor the king (or Nyim) named Mishe miShyaang maMbul, who ruled in the early eighteenth century. In a time of transition and conflict throughout the region, the statue helped define the majesty of his office. The full face and softly rounded torso of this ndop, or wooden figure, show that the king was well fed. His dignified, remote expression is enhanced by the abstracted shapes of his mouth and eyes. Clearly, the ndop is highly idealized, an evocation of kingship rather than an individual portrait. Mishe miShyaang maMbul was credited with inventing a type of drum with a handle shaped like a human hand, and the drum links him to this statue; subsequent images of other kings can be identified because they display other distinguishing emblems. This Nyim wears only a beaded sash, a few bands around his arms, and a distinctive flat crown. In contrast, Kuba kings of the twentieth century were covered from head to toe in an elaborate costume that weighed as much as they did.

During the king’s lifetime, the statue was said to be a repository for his spirit, but after his death it became a commemorative image as well as a source of sacred energy. In 1909, the Nyim gave this valuable statue to a visiting official of the Belgian government who had promised to protect the Kuba from the atrocities that the early colonial authorities, plantation owners, and traders were inflicting on the region. The family of this Belgian politician sold the ndop to the Brooklyn Museum, New York, in 1961.

The bare-chested man sits cross-legged, with eyes closed peacefully, as if in meditation. An object in front of him looks like an oversized thimble with a human hand mounted on the side. He wears a headdress consisting of a round band topped by a flat, rectangular section.

Karagwe

CAST-IRON SCULPTURES OF KARAGWE The Kuba Nyim, like the Manikongo and many other kings in Central Africa, have been characterized as blacksmiths—whether or not they actually possessed blacksmithing skills. Allusions to ironmaking are present in many royal ceremonies, particularly those that mark a ruler’s ascension to power. Figures and divination instruments from some Central African regions even incorporate images of the blacksmith’s anvil. In the valleys and escarpments of the Great Rift Valley, the kingdoms of Buganda, Ntoro, and tiny Karagwe were founded in the fourteenth or fifteenth centuries by what were believed to be divine rulers, kings whose royal insignia were made of iron.

Rumanika

Ndagara

Rumanika I (ruled 1855–81) was the king of Karagwe, the southernmost of these kingdoms, in the late nineteenth century. The European explorers and adventurers who visited his palace were impressed by the hundreds of cast-iron sculptures he displayed. Most were abstracted images of cattle with multiple, tentacle-like horns, a celebration of the animals that were a source of prestige and wealth in the region. One example represents a bull (Fig. 49.13). The bull’s head is in the form of a triangular anvil, reminding viewers of the king’s important association with ironmaking technologies. The horns sweep upward, and the elongated legs and horns exaggerate these features of the humped cattle of the region. Rumanika claimed that this iron statue (and the rest of his iron regalia) had been forged by his father and predecessor, King Ndagara (ruled c. 1820–53).

The highly stylized figure has enormous, curving horns, a triangular head, and a hump on its back.