THE DEVELOPMENT OF NOTATION

ORAL TRANSMISSION

We can trace the development of the liturgy of the Western Church because the words were written down. Yet the melodies were learned by hearing others sing them, a process called oral transmission, leaving no written traces. We have only one fragment of Christian music before the ninth century—a hymn to the Trinity from the late third century found on a papyrus at Oxyrhynchos in Egypt and written in ancient Greek notation. But this notation had been forgotten by the seventh century, when Isidore of Seville (ca. 560–636) wrote that “Unless sounds are remembered by man, they perish, for they cannot be written down.”

How chant melodies were created and transmitted without writing has been a subject of much study and controversy. Recent studies of memory and oral transmission suggest that medieval singers composed new songs by singing aloud, drawing on existing conventions and formulas, and fixed the melodies in their minds through repetition. Chant was learned by rote and sung from memory, requiring singers to retain hundreds of melodies, many sung only once a year. Chants that were simple, were sung frequently, or were especially distinctive and memorable may have been passed down with little change. Other chants may have been improvised or composed orally within strict conventions, following a given melodic contour and using opening, closing, and ornamental formulas appropriate to a particular text or place in the liturgy. This process resembles other oral traditions; for example, epic singers from the Balkans recited long poems seemingly by rote but actually using formulas associating themes, syntax, meters, line endings, and other elements.

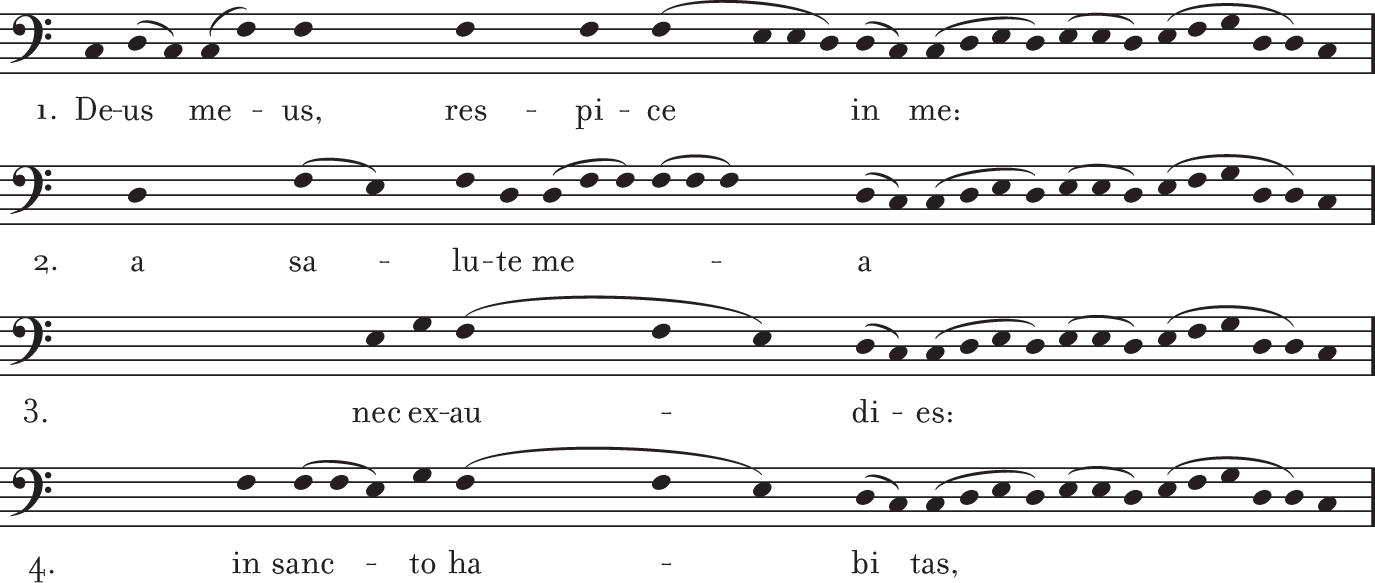

EXAMPLE 2.1 The second phrases of the first four verses of the Tract Deus, Deus meus

Traces of oral composition We can find evidence for such oral composition in the chants themselves. Example 2.1 compares parallel phrases from the first four verses of Deus, Deus meus, a Tract (for the categories of chant, see Chapter 3). Each phrase hovers around F, then descends to close with the same cadential figure at the midpoint of the verse. No two verses are exactly the same, but each features the same fund of formulas, which also appear in many other Tracts. Since Tracts were originally performed by a soloist, it seems likely that over the centuries singers developed a standard pattern, consisting of a general melodic contour and a set of formulas to delineate the phrases in each verse, and varied it to fit the syllables and accentuation of the particular text for each verse or chant. When the melodies were written down, these variations were preserved.

STAGES OF NOTATION

Individual variation was not suitable if the chants were to be performed in the same way each time in churches across a wide territory. During the eighth century, attempts were made to bring Roman chants to the Frankish lands and to train Frankish singers how to reproduce them. But as long as this process depended on memory and on learning by ear, melodies were subject to change, and accounts from both Roman and Frankish perspectives tell of melodies being corrupted as they were transmitted to the north. What was needed to stabilize the chants was notation, a way to write down the music. The earliest surviving books of chant with music notation date from the late ninth century, but their substantial agreement suggests to some scholars that notation may already have been in use in Charlemagne’s time or soon thereafter. We have some written testimony to support this view, though scholars differ in interpreting the evidence, and the first definitive references to notation date from about 850. Whenever notation was invented, writing down the melodies was an attempt to ensure that from then on each melody would be sung in essentially the same way each time and in each place it was sung. Thus notation was both a result of striving for uniformity and a means of perpetuating that uniformity.

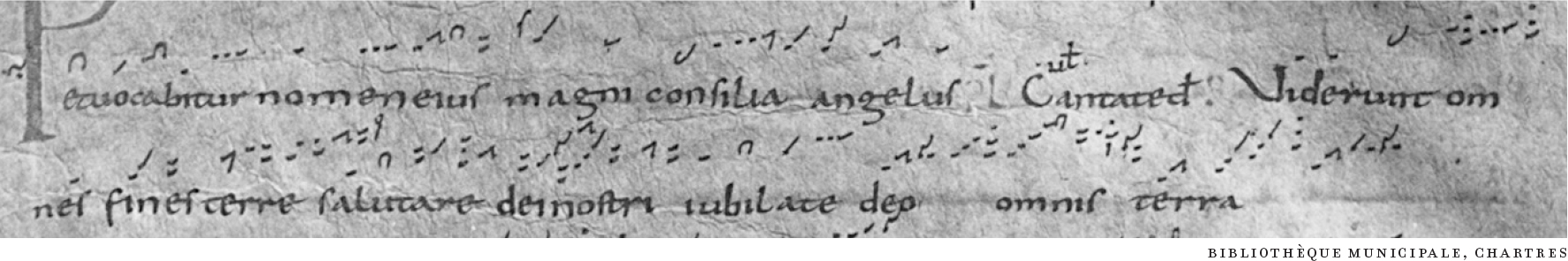

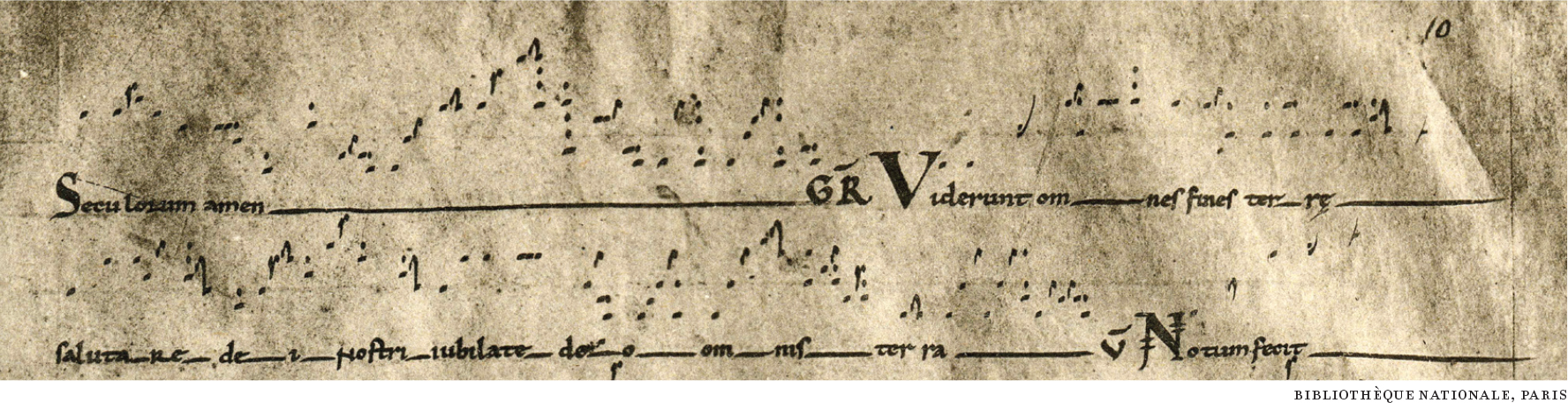

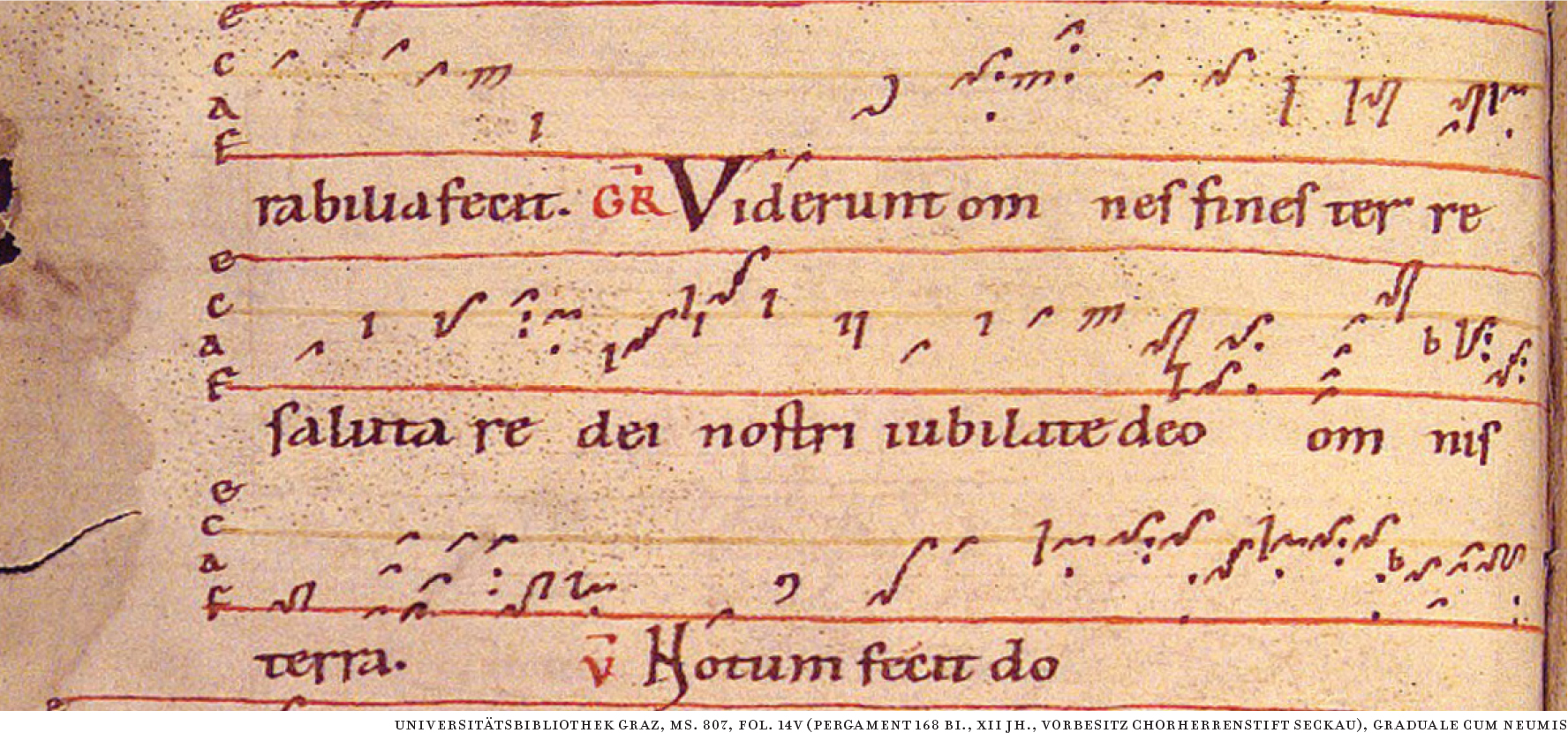

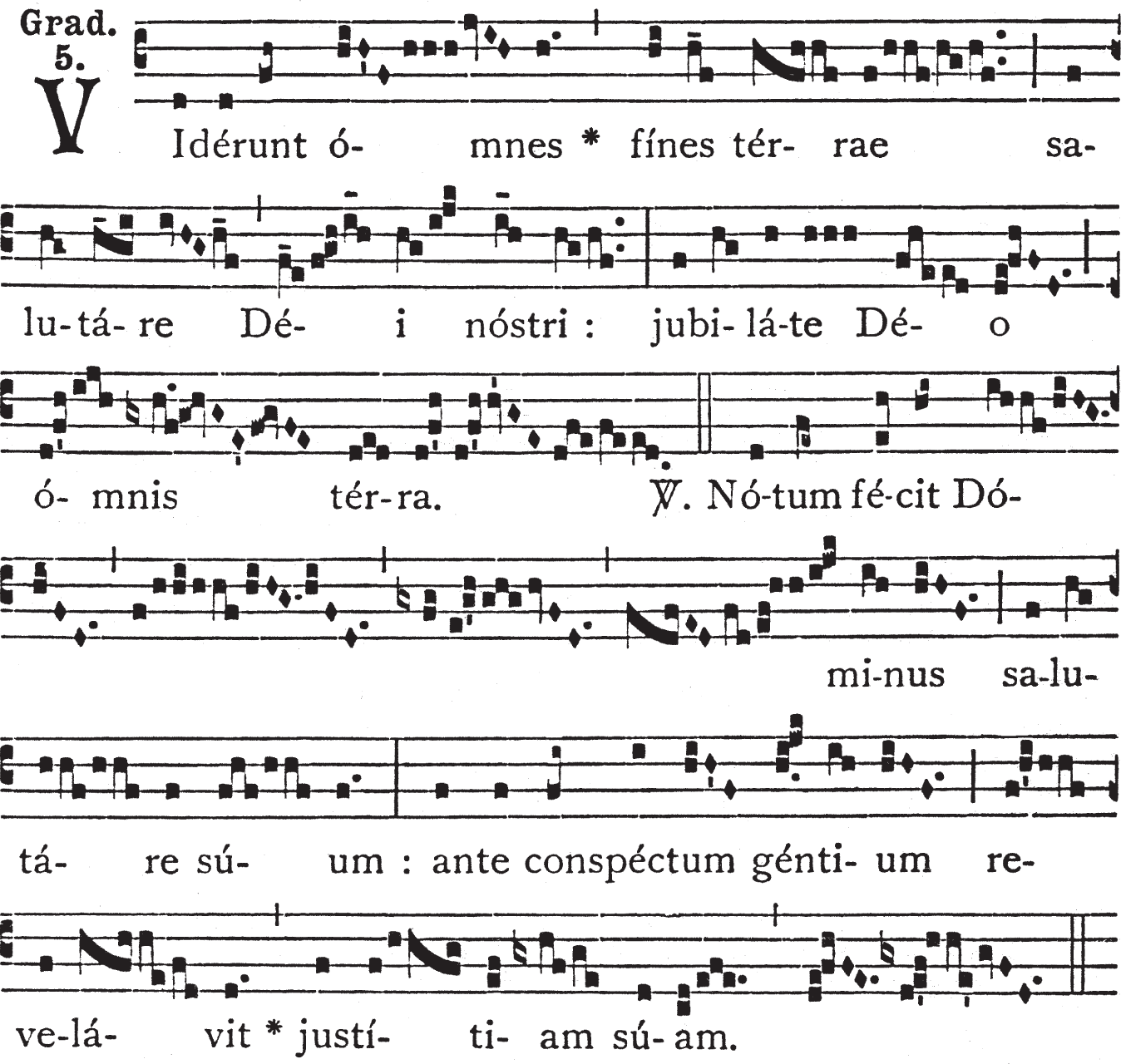

Notation developed through a series of innovations, each of which made the melodic outline more precise. The significant historical steps are shown in Figures 2.6–2.8, with modern equivalents in Examples 2.2–2.3. All show the Gradual Viderunt omnes from the Mass for Christmas Day (NAWM 3d).

Neumes In the earliest notations, signs called neumes (Latin neuma, meaning “gesture”) were placed above the words, as in Figure 2.6, to indicate the melodic gesture for each syllable, including the number of notes, whether the melody ascended, descended, or repeated a pitch, and perhaps rhythm or manner of performance. Neumes may have derived from signs for inflection and accent that scholars developed to aid in declaiming Latin texts. Because neumes did not denote specific pitches or intervals, they served as reminders of the melodic shape but could not be read at sight by someone who did not already know the melody. Melodies still had to be learned by ear.

Heighted neumes In the tenth and eleventh centuries, scribes placed neumes at varying heights above the text to indicate the relative size as well as direction of intervals, as in Figure 2.7. These are called heighted neumes. This approach made the pitch contour clearer but was not adopted everywhere because it apparently sacrificed the more subtle performance indications in neumatic notation.

Lines, clefs, staff The scribe of this manuscript scratched a horizontal line in the parchment corresponding to a particular note and oriented the neumes around that line. This was a revolutionary idea: a musical sign that did not represent a sound, but clarified the meaning of other signs. In other manuscripts, the line was labeled with a letter for the note it represented, most often F or C because of their position just above the semitones in the diatonic scale; these letters evolved into our clef signs, and with them each pitch in the melody was clear. The eleventh-century monk Guido of Arezzo (ca. 991–after 1033) suggested an arrangement of lines and spaces, using a line of red ink for F and of yellow ink for C and scratching other lines into the parchment. Letters in the left margin identify each line. This scheme was widely adopted, and the neumes were reshaped to fit the arrangement, as shown in Figure 2.8. From this system evolved a staff of four lines a third apart, the ancestor of our modern five-line staff.

Reading music The use of lines and letters, culminating in the staff and clefs, enabled scribes to notate pitches and intervals precisely. In practice, pitch was still relative, as it had been for the Greeks; a notated chant could be sung higher or lower to suit the singers, but the notes relative to each other would form the same intervals. The new notation also freed music from its dependence on oral transmission. With his notation, Guido demonstrated that a singer could “learn a verse himself without having heard it beforehand” simply by reading the notes. This achievement was as crucial for the history of Western music as the invention of writing was for the history of language and literature.

Notation and memory Music could now be made visible in notation, but it was still a sounding art. Oral transmission of music continued alongside written transmission, as it does today. Church choirs in many places continued to sing most chant from memory for centuries. Notation proved a valuable tool for memorization, because it is easier to remember words and music if we visualize them in our mind’s eye. Moreover, notation made it possible to memorize music exactly, by fixing each note in a document that we can check if our memory fails us. Thus notation did not replace memory but enabled singers to learn hundreds of chants more quickly and to reproduce them verbatim each time.

Rhythm Staff notation with neumes conveyed pitch but not duration. Some manuscripts contain signs for rhythm, but scholars have not agreed on their meaning. One modern practice is to sing chants as if all notes had the same basic value; notes are grouped in twos or threes, and these groups are flexibly combined into larger units. This interpretation, worked out in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by the Benedictine monks of the Abbey of Solesmes in France under Dom Joseph Pothier and Dom André Mocquereau, was approved by the Catholic Church as conforming with the spirit of the liturgy. Whatever differences in duration there may have been in early practice, chant was almost certainly relatively free rather than metered in rhythm. Its movement has been compared to the flow of sand through an hourglass, the medieval standard for timekeeping, as opposed to the ticking of a clock.

SOLESMES CHANT NOTATION

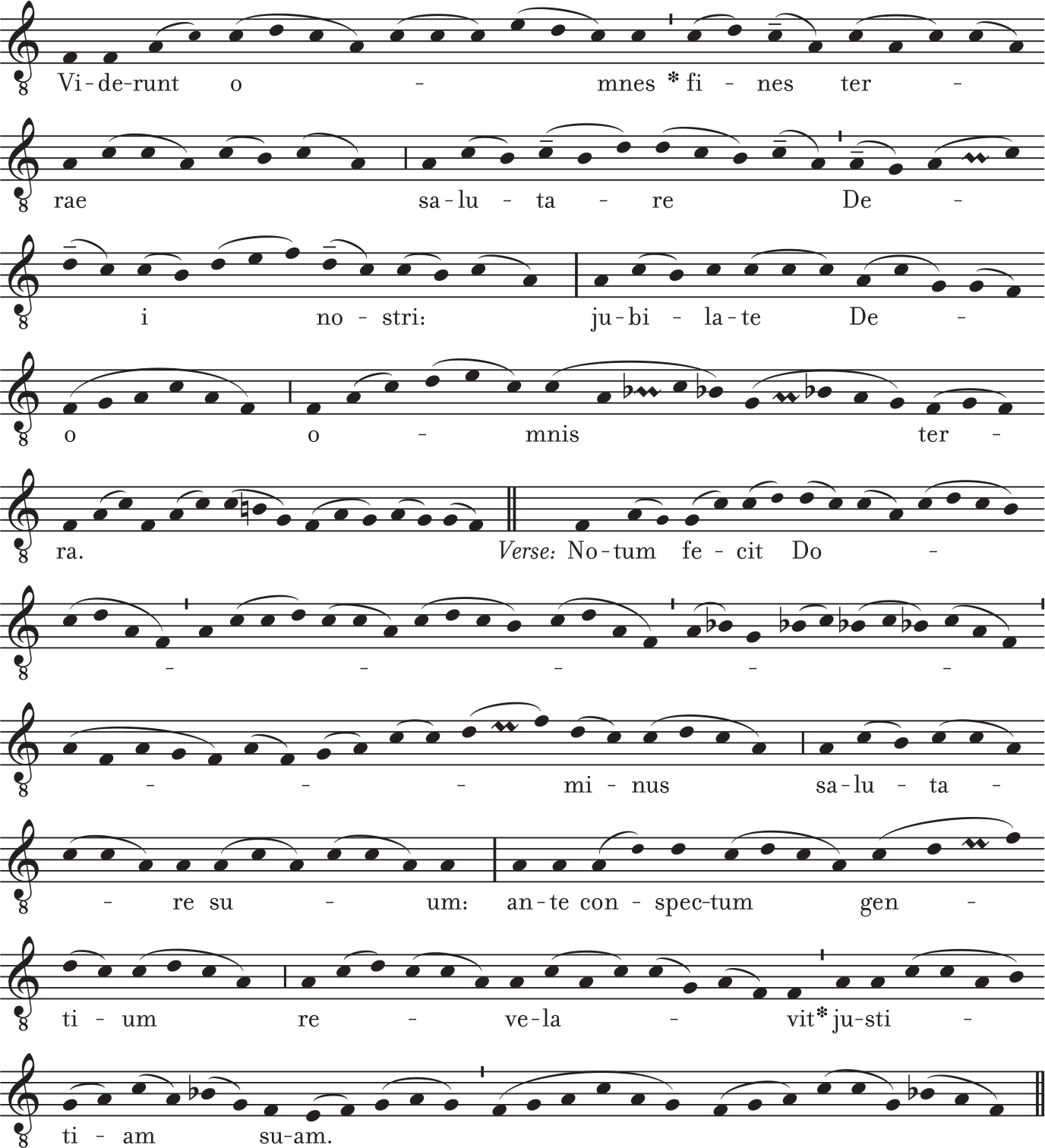

The Solesmes monks prepared modern editions of chant, which Pope Pius X proclaimed in 1903 as the official Vatican editions. Intended for use in church rather than historical study, they use a modernized form of chant notation. Examples 2.2 and 2.3 show the Gradual Viderunt omnes in Solesmes notation and in transcription, to facilitate comparison with each other and with the medieval neumatic notations in Figures 2.6–2.8. The staff in chant notation has four lines, one of which is designated by a clef as either middle C ( ) or the F below middle C (

) or the F below middle C ( ), like our modern C clefs and bass clef.

), like our modern C clefs and bass clef.

EXAMPLE 2.2 The Gradual Viderunt omnes in Solesmes chant notation

Reading chant notation The notes and note groups are called neumes. A neume may carry only one syllable of text. Neumes are read left to right, except that when one note is below another the lower note is sung first; thus the melody on “fines” in Example 2.2 is c′–d′–c′–a. (Compare Figures 2.7 and 2.8, in which vertically stacked notes are sung from the top down instead of from the bottom up.) An oblique neume ( ) indicates three notes, so that “terrae” begins c′–a–c′. Diamond-shaped notes appear in descending patterns, as on “omnes,” as a way to save space; they may receive the same values as square ones, although their name (currentes, meaning “running”) suggests some quickening. The small notes indicate partially closing the mouth on a voiced consonant at the end of a syllable, as on the “n” in “Viderunt” in the first staff. The wavy line in ascending figures (

) indicates three notes, so that “terrae” begins c′–a–c′. Diamond-shaped notes appear in descending patterns, as on “omnes,” as a way to save space; they may receive the same values as square ones, although their name (currentes, meaning “running”) suggests some quickening. The small notes indicate partially closing the mouth on a voiced consonant at the end of a syllable, as on the “n” in “Viderunt” in the first staff. The wavy line in ascending figures ( , called quilisma), as on “omnis” in the third staff, may have indicated a vocal ornament. The only accidentals used are flat and natural signs, which can appear only on B. Unless it appears in a signature at the beginning of a line, a flat is valid only until the beginning of the next word or vertical division line; thus in “omnis terra” in the third staff of Example 2.2, the first word features B

, called quilisma), as on “omnis” in the third staff, may have indicated a vocal ornament. The only accidentals used are flat and natural signs, which can appear only on B. Unless it appears in a signature at the beginning of a line, a flat is valid only until the beginning of the next word or vertical division line; thus in “omnis terra” in the third staff of Example 2.2, the first word features B (marked on “-mnis”) and the second B♮ (because the flat has been canceled by beginning a new word).

(marked on “-mnis”) and the second B♮ (because the flat has been canceled by beginning a new word).

EXAMPLE 2.3 The Gradual Viderunt omnes transcribed in modern notation

The Solesmes editions include interpretive signs that are not in the medieval manuscripts. A dot doubles the value of a note, and a horizontal dash indicates a slight lengthening, as on “fines.” Vertical lines of varied lengths show the division of a melody into sections (double barline), periods (full barline), phrases (half-barline), and smaller units (a stroke through the uppermost staff line). An asterisk in the text shows where the chorus takes over from the soloist.

- notation

A system for writing down musical sounds, or the process of writing down music. The principal notation systems of European music use a staff of lines and signs that define the pitch, duration, and other qualities of sound.

- neume

A sign used in notation of chant to indicate a certain number of notes and general melodic direction (in early forms of notation) or particular pitches (in later forms).

- heighted neumes

In an early form of notation, neumes arranged so that their relative height indicated higher or lower pitch.