NAWM 4a Anonymous, Chants from Vespers for Christmas Day: First Psalm with Antiphon: Antiphon Tecum principium and psalm Dixit Dominus

GENRES AND FORMS OF CHANT

Given the varied styles and histories of the chants for the Mass and Office, it will be helpful to treat them in broad categories, beginning with syllabic types, proceeding to neumatic and melismatic ones, and considering the Mass Ordinary chants separately at the end. (For a discussion of chant types in liturgical order and context, see the commentary for NAWM 3 and NAWM 4.) Each type of chant has a distinctive form in both text and music, and a particular way to perform it. While examining the chants, we should not lose sight of who sings them and in what places in the liturgy, since these factors explain the differences in musical style.

RECITATION FORMULAS

The simplest chants are the formulas for intoning prayers and Bible readings, such as the Collect, Epistle, and Gospel. Here the music’s sole function is to project the words clearly, without embellishment, so the formulas are spare and almost entirely syllabic. The text is chanted on a reciting note, usually A or C, with brief motives marking the ends of phrases, sentences, and the entire reading; some formulas also begin phrases with a rise to the reciting note. These recitation formulas are quite old, predating the system of modes, and are not assigned to any mode. They are sung by the priest or an assistant, with occasional responses from the choir or congregation. Priests were not necessarily trained singers, and they had a lot of text to recite, so it makes sense that their melodies were simple and in a very limited range.

PSALM TONES

Slightly more complex are the psalm tones, formulas for singing psalms in the Office. These are designed so they can be adapted to fit any psalm. There is one psalm tone for each of the eight modes, using the mode’s reciting tone as a note for reciting most of the text. These psalm tones are still used today in Catholic, Anglican, and other churches, continuing a practice that is well over twelve hundred years old.

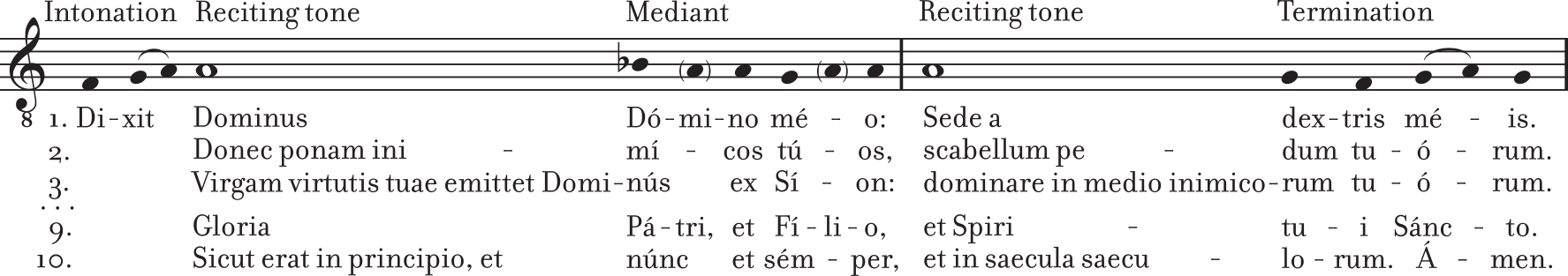

Example 3.1 shows the first psalm for Vespers on Christmas Day, Dixit Dominus (Psalm 109 in the Latin Bible, 110 in the Hebrew Scriptures and most modern translations), using the tone for mode 1 (NAWM 4a). As the example illustrates, each psalm tone consists of an intonation, a rising motive used only to begin the first verse; recitation on the reciting tone of the mode; the mediant, a cadence for the middle of each verse; further recitation; and a termination, a final cadence for each verse. The structure of the music exactly reflects that of the text. Each psalm verse is composed of two statements, the second echoing or completing the first. The mediant marks the end of the first statement, and the termination signals the end of the verse; both introduce melodic motion around the last one or two accented syllables of the phrase. The last verse of the psalm is followed by the Lesser Doxology, a formula of praise to the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit), sung to the same psalm tone and shown here as verses 9–10. The addition of this brief text puts the psalm, from the Hebrew Scriptures, firmly into a Christian framework. Somewhat more elaborate variants of the psalm tones are used for canticles in the Office and for the psalm verse in the Introit at Mass (NAWM 3a).

NAWM 3a Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Introit: Puer natus est nobis

EXAMPLE 3.1 Office psalm, Dixit Dominus, Psalm 109 (110)

2. Until I make Thy enemies Thy footstool.

3. The Lord sends the rod of Thy strength forth from Zion: rule in the midst of Thy enemies. . . .

9. Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit.

10. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end. Amen.

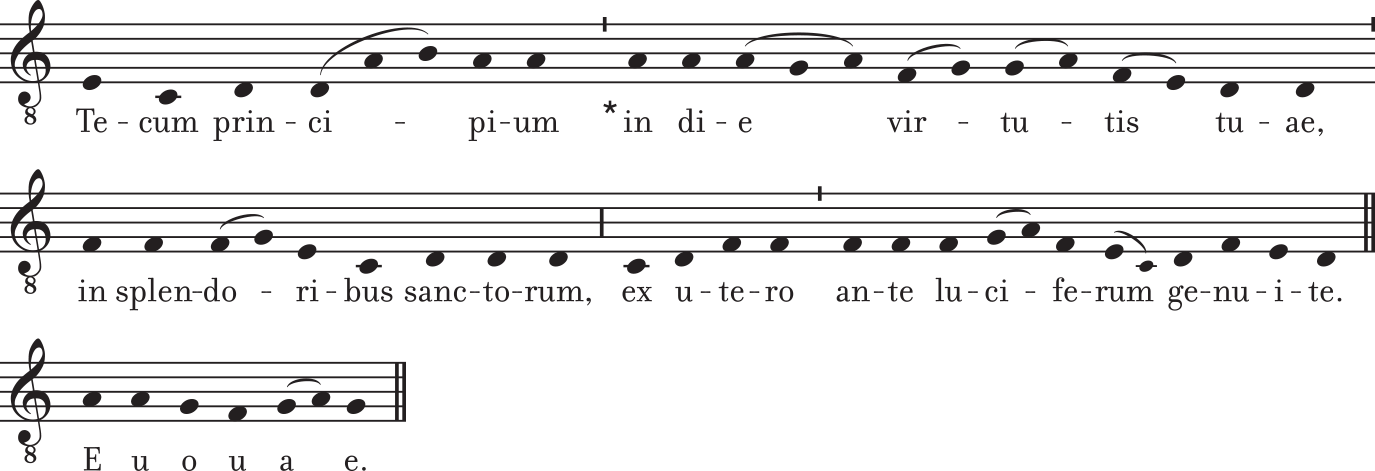

EXAMPLE 3.2 Office antiphon, Tecum principium

OFFICE ANTIPHONS

An Office psalm or canticle is not complete in itself, but is preceded and followed by an antiphon. Since the cycle of the 150 psalms is sung every week while the antiphon varies with each day in the church calendar, each psalm is framed by many different antiphons during the year. The text of the antiphon, whether from the Bible or newly written, often refers to the event or person being commemorated that day, placing the words of the psalm in a specific ceremonial context. On Christmas Day, the first psalm at Vespers is paired with the antiphon Tecum principium, shown in Example 3.2 (NAWM 4a). Here the text for the antiphon is the fourth verse of the psalm, whose images of dominion, strength, the womb, and divine parentage were understood by Christians to herald the birth of Jesus, being celebrated at this Vespers service.

NAWM 4a Anonymous, Chants from Vespers for Christmas Day: First Psalm with Antiphon: Antiphon Tecum principium and psalm Dixit Dominus

Mode and psalm tone The mode of the antiphon determines the mode for the psalm tone. The antiphon is in mode 1, so the psalm tone for mode 1 must be used for the psalm, as in Example 3.1. Because antiphons begin in various ways, medieval singers developed several terminations for each psalm tone, to lead appropriately to different opening notes or gestures. The termination to be used with a particular antiphon is shown at the end of the antiphon, using the vowels for the last six syllables of the Doxology, E u o u a e (for saEcUlOrUm AmEn), as in Example 3.2. The termination does not necessarily end on the first note of the antiphon, as long as the succession is smooth; here, the medieval musicians chose G as the most suitable ending note to lead back to the antiphon’s opening notes, E–C–D. Thus the psalm tone need not close on the final of the mode, but the antiphon does.

Performance The manner of performing psalms and canticles with antiphons has varied over time. Early descriptions include direct performance by soloists, responsorial alternation between a soloist and choir or congregation, and antiphonal alternation between two singers or groups. In medieval monastic practice, the entire community of monks or nuns was divided into two choirs singing the psalm antiphonally, alternating verses or half-verses; the antiphon could be sung by soloists, reading from the Antiphoner, or by all, singing from memory. Antiphonal performance was suggested by the division of each psalm verse into two parts and encouraged by the layout of medieval churches, with the choir arranged in two sets of stalls flanking the altar, as shown in Figure 3.5.

In most modern performances, the cantor, the leader of the choir, sings the opening words of the antiphon to set the pitch (up to the asterisk in modern editions), and the full choir completes the antiphon; the cantor sings the first half of the first psalm or canticle verse, and half the choir completes it; the two half-choirs alternate verses or half-verses; and the full choir joins together for the reprise of the antiphon.

Office antiphons are simple and mostly syllabic, reflecting their historical association with group singing and the practical fact that over thirty are sung each day, making great length burdensome. Yet they are fully independent melodies. Tecum principium (Example 3.2) illustrates the elegance of even simple Gregorian chants. Text phrases and accents are clearly delineated. Each phrase centers around and cadences on important notes of the mode while tracing a unique arch. The opening phrase circles around the final D, leaps dramatically to the reciting tone A, then meanders down to D; the last two phrases both hover around F, then sink to encircle and close on D. Antiphon and psalm tone combine to create a piece with two contrasting styles, free melody and recitation, in which the outer sections emphasize the final, the longer central section the reciting tone.

OFFICE HYMNS

Hymns are the most familiar type of sacred song, practiced in almost all branches of Christianity from ancient times to the present. The choir sings a hymn in every Office service. Hymns are strophic, consisting of several stanzas that are all sung to the same melody. Stanzas may be four to seven lines long, and some include rhymes. Melodies often repeat one or more phrases, producing a variety of patterns.

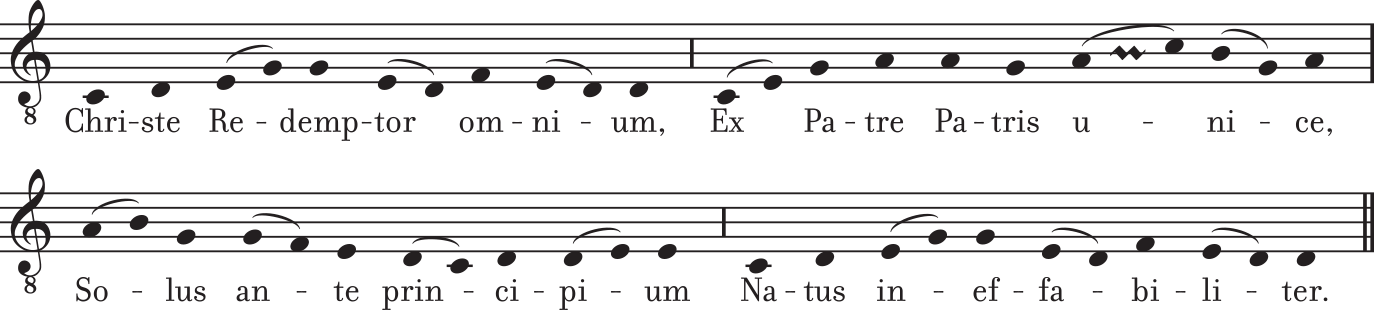

The hymn Christe Redemptor omnium, sung at Vespers on Christmas Day (NAWM 4b) and shown in Example 3.3, welcomes the birth of Christ as redeemer, begotten by God and born of the Virgin Mary, who took on human form and came to save the world. Like most Gregorian hymns, it has one note on most syllables with two or three notes on others. It is in mode 1, and each phrase and the melody as a whole have a shapely rise and fall. The first phrase ascends from C to G and falls to the final D; the second climbs to high C and cadences on the reciting tone A; the third phrase steps down to low C and rises back to E; and the final phrase repeats the first, to close on D. This kind of contour, moving mostly by seconds and thirds to a peak and descending to a cadence, has been typical of western European melodies ever since.

NAWM 4b Anonymous, Chants from Vespers for Christmas Day: Hymn: Christe Redemptor omnium

EXAMPLE 3.3 Hymn, Christe Redemptor omnium

ANTIPHONAL PSALMODY IN THE MASS

Psalmody, the singing of psalms, was part of the Mass as well as the Office. In the early Mass, psalms sung antiphonally with antiphons were used to accompany actions: the entrance procession and giving communion. These became the Introit and the Communion respectively. Over time, the opening procession of the Mass was shortened and the faithful came to receive communion less frequently. Eventually both chants were shifted to come after the rituals rather than accompanying them. Both chants were abbreviated, the Communion to the antiphon alone, the Introit to the antiphon, one psalm verse, Lesser Doxology, and the reprise of the antiphon (see NAWM 3a).

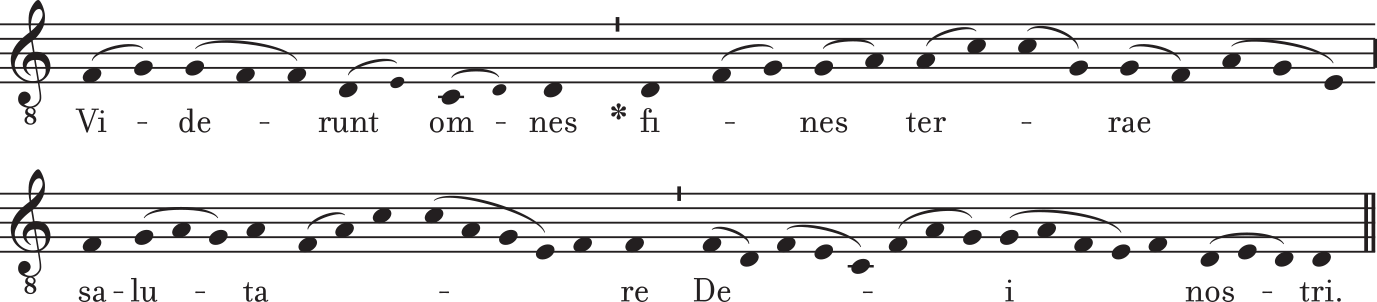

Because the greater solemnity of the Mass called for greater musical splendor, Mass antiphons are more elaborate than Office antiphons, typically neumatic with occasional short melismas. We can see this in Example 3.4, the Communion from Mass for Christmas Day, Viderunt omnes (NAWM 3j), where most syllables are sung with one to five notes. Although short melismas of eight or nine notes occur on two syllables, they are brief in comparison with the long melismas of melismatic chants like the Allelulia in Example 3.5, so the overall style of the Communion chant is neumatic. Neumatic chants are more ornate than syllabic ones, yet the characteristics of previous examples are still apparent: articulated phrases; motion mostly by steps and thirds; and arching lines that rise to a peak and sink to the cadence, circling around and closing on important notes in the mode (again mode 1). Here higher notes and longer note groups emphasize the most important accents and words.

RESPONSORIAL PSALMODY IN OFFICE AND MASS

Early Christians often sang psalms responsorially, with a soloist performing each verse and the congregation or choir responding with a brief refrain. The responsorial psalms of Gregorian chant—the Office responsories and the Gradual, Alleluia, and Offertory in the Mass—stem from this practice. As we will see in later eras, singers and instrumental virtuosos, given the opportunity, would often add embellishments and display their skill through elaborate passagework. So it should come as no surprise that over the centuries of oral transmission these chants assigned to soloists became the most melismatic. They are the musical peaks of the service, moments when the words for once seem secondary to the expansive melody filling the church.

The different genres of responsorial psalm assumed different configurations. The text was usually shortened to a single psalm verse with a choral respond preceding and sometimes following the verse.

Office responsories Office responsories take several forms, but all include a respond, a verse, and a full or partial repetition of the respond. Matins, celebrated between midnight and sunrise, includes nine Bible readings, each followed by a Great Responsory that ranges from neumatic to melismatic. Several other Office services include a brief Bible reading followed by a Short Responsory that is neumatic rather than melismatic.

EXAMPLE 3.4 Communion, Viderunt omnes

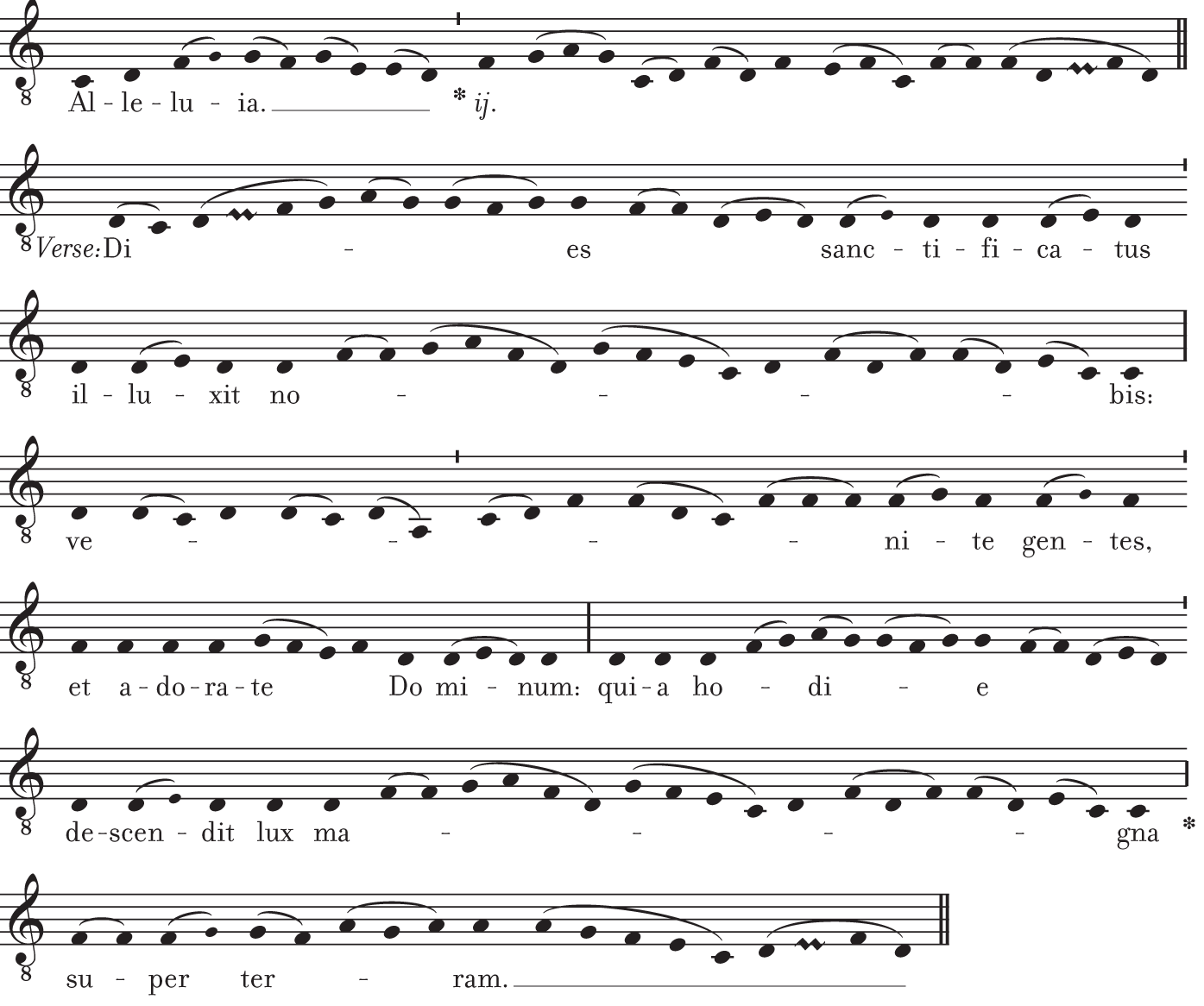

EXAMPLE 3.5 Alleluia Dies sanctificatus

Graduals Graduals are considerably more melismatic than responsories. Viderunt omnes, the Gradual for Christmas Day (Example 2.3 and NAWM 3d), contains a melisma of fifty-two notes on “Dominus” and three other melismas ten to twenty notes long. In some Graduals, the music at the end of the verse repeats or varies the end of the respond. In performance, the cantor begins the respond and the choir completes it; then one or more soloists sing the verse, and the choir joins in on the last phrase.

NAWM 3d Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Gradual: Viderunt omnes

Alleluias Alleluias include a respond on the word “alleluia,” a psalm verse, and a repetition of the respond. The final syllable of “alleluia” is extended by an effusive melisma called a jubilus. St. Augustine and others regarded such long melismas as an expression of a joy beyond words, making them especially appropriate for Alleluias. Example 3.5 shows Alleluia Dies sanctificatus, from the Mass for Christmas Day (NAWM 3e). The soloist sings the first part of the respond on “alleluia” (to the asterisk), then the choir repeats it (as indicated by ij, the sign for repetition) and continues with the jubilus. The soloist sings the verse, with the choir joining on the last phrase (at the asterisk), then the soloist repeats the first part of the respond, and the choir joins at the jubilus. In many Alleluias, the music at the end of the verse repeats all or part of the respond melody; here, there is instead a varied repetition of the opening of the verse (at “quia hodie descendit lux magna”).

NAWM 3e Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Alleluia Dies sanctificatus

Despite the longer and more effusive melody, the characteristics seen in other chants are evident, including articulated phrases, motion primarily by steps and thirds, and gently arching contours. This Allelulia is in mode 2, the plagal mode on D. It ranges an octave from low A to high A, centers on the reciting tone F in several places, cadences most often on D, and ends both respond and verse on D. There are several long melismas, most focused around F and D, and some passages that resemble recitation on a single note, as at “sanctificatus” and “et adorate.” But underneath the intricacies is the same sense of a melodic curve as in syllabic and neumatic chants.

Offertories Offertories are as melismatic as Graduals but include the respond only (see NAWM 3g). In the Middle Ages, they were performed during the offering of bread and wine, with a choral respond and two or more very ornate verses sung by a soloist, each followed by the second half of the respond. When the ceremony was curtailed, the verses were dropped.

NAWM 3g Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Offertory: Tui sunt caeli

Tracts Tracts (from Latin tractus, “drawn out”) are the longest chants in the liturgy, with several psalm verses set in very florid style. Though now often performed like Graduals, they were originally direct solo psalmody, with no responses and thus no respond. Instead, each verse combines recitation with florid melismas. All Tracts are in mode 2 or mode 8, and the sequence of cadences, the melodic outline, and many of the melismas are shared between verses and between different Tracts in the same mode, indicating that the written melodies resulted from a tradition of oral composition based on formulas (see Chapter 2 and Example 2.1).

In all these chants derived from responsorial or direct psalmody, we see the hallmarks of solo performance: long, virtuosic melismas that display the voice, and passages that resemble improvised embellishment of a simple melodic outline. All but the Offertory are attached to Bible readings, ornamenting and thereby honoring that most holy text in a musical parallel to the colorful illuminations that decorate medieval Bible manuscripts.

CHANTS OF THE MASS ORDINARY

The sung portions of the Mass Ordinary were originally performed by the congregation to simple syllabic melodies. But over the centuries, liturgical Latin became harder for members of the congregation to understand or speak, as the language of daily life gradually evolved from Latin into new vernacular tongues, such as Italian, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. Perhaps because of this linguistic gulf, church leaders reduced the congregation’s participation in the Mass, and the choir took over singing the Ordinary chants. From the ninth century on, church musicians composed many new melodies for the Ordinary that were more ornate, suitable for performance by trained singers. These chants tend to be in a later style than most Proper chants, with clearer pitch centers, strong projection of the mode, more melodic repetition, a more individual melodic profile, and little or no recitation on a single note. The musical forms used in Ordinary chants vary, but often reflect the shape of their texts.

Gloria and Credo The Credo (see NAWM 3f) was always set in syllabic style because it has the longest text and because, as the statement of faith, it was the last to be reassigned to the choir. The Gloria also has a long text, but most settings are neumatic (see NAWM 3c). Gloria and Credo melodies often feature recurring motives but have no set form. In both cases, the priest intones the opening words and the choir completes the chant.

NAWM 3f Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Credo

NAWM 3c Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Gloria

Sanctus and Agnus Dei Most melodies for the Sanctus and Agnus Dei are neumatic. Their texts include repetition, so melodies composed for them often have musical repetition as well. The Sanctus (see NAWM 3h) begins with the word “Sanctus” (Holy) stated three times, and the third statement often echoes the music for the first. The second and third sections of the text both end with the phrase “Hosanna in excelsis” (Hosanna in the highest) and often are set to variants of the same music (producing the form ABB′) or use the same melody for the Hosanna (creating the form A BC DC). The Agnus Dei (see NAWM 3i) states a prayer three times, altering the final words the last time. Some settings use the same music for all three statements (AAA); others are in ABA form or close all three sections with the same music (AB CB DB).

NAWM 3h Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Sanctus

NAWM 3i Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Agnus Dei

Kyrie The Kyrie text is even more repetitive, with three statements each of “Kyrie eleison,” “Christe eleison,” and “Kyrie eleison.” The brief text invites a florid setting, and most Kyrie melodies have melismas on the last syllables of “Kyrie” and “Christe” and the first syllable of “eleison.” The text repetition is reflected in a variety of musical forms, such as AAA BBB AAA′, AAA BBB CCC′ (as in NAWM 3b), or ABA CDC EFE′. The Kyrie is usually performed antiphonally, with half-choirs alternating statements. The final “Kyrie” is often extended by a phrase, allowing each half-choir to sing a phrase before both join on the final “eleison.”

NAWM 3b Anonymous, Mass for Christmas Day: Kyrie

Cycles of Ordinary chants Starting in the thirteenth century, scribes often grouped Ordinary chants in cycles, with one setting of each text except the Credo. Similar cycles appear in the Liber usualis. Although there were many melodies for Ite, missa est in the Middle Ages, in the Liber usualis cycles this is set to the melody of the first Kyrie.

STYLE, USE, AND HISTORY

Each type of chant is unique, reflecting its role and history. Recitation formulas were valued for their ability to project the words clearly in large spaces and for being easy to memorize and apply to many texts. Antiphons and hymns added melodic interest, and during Mass the neumatic chants of the choir adorned the service. Melismatic chants were valued for their decorative beauty and became the musical jewels of the liturgy, sung by soloists and choir when no ritual actions competed for attention. As the most elaborate chants in the repertory, they were used especially to embellish the readings from Scripture. When revisions in the liturgy changed the function of a chant or who performed it, musicians responded by changing its form or style, as when the Introit and Communion were shortened, or when more-ornate melodies were written for the Ordinary chants after they were reassigned to the choir.

But all these chants also shared a common history with ancient roots. Their creators drew on psalm texts, continuing Jewish practice as adapted by early Christians; used modes and melodic formulas, as in the Jewish, Near Eastern, and Byzantine traditions; and emphasized correct phrasing and declamation of the text, borrowing from classical Latin rhetoric. Both the diversity of the chant repertory and the melodic and structural features most chants share become more apparent when we know the histories of plainchant as a whole and of the many individual types of chant.

- psalm tone

A melodic formula for singing psalms in the Office. There is one psalm tone for each mode.

- Lesser Doxology

A formula of praise to the Trinity, used with psalms, Introits, and other chants.

- cantor

In the medieval Christian church, the leader of the choir. In Jewish synagogue music, the main solo singer.

- strophic

Of a poem, consisting of two or more stanzas that are equivalent in form and can each be sung to the same melody; of a vocal work, consisting of a strophic poem set to the same music for each stanza.

- psalmody

The singing of psalms.

- respond

The first part of a responsorial chant, appearing before and sometimes repeated after the psalm verse.

- jubilus

(Latin) In chant, an effusive melisma, particularly the melisma on “-ia” in an Alleluia.

- cycle

A group of related works, comprising movements of a single larger entity. Examples include cycles of chants for the Mass Ordinary, consisting of one setting each of the Kyrie, Gloria, Sanctus, and Agnus Dei (and sometimes also Ite, missa est); the polyphonic mass cycle of the fifteenth through seventeenth centuries; and the song cycle of the nineteenth century.