SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Explain the processes of asexual (vegetative) reproduction and sexual reproduction.

- Distinguish the key traits of fungi, algae, amebas, ciliates, and hemoflagellates.

- Distinguish between microbial and invertebrate parasites.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

Microbial eukaryotes—including protozoa, fungi, and algae—play key roles in all ecosystems. In the oceans, algae and protozoa (collectively called protists) provide the base of a vast food web that feeds fish and marine mammals. In forests, many fungi break down wood for nutrients, while others connect tree roots in a vast network of nutrient sharing. This chapter explores the diversity of microbial eukaryotes. In addition, we will introduce certain differentiated animals (helminths and arthropods) that act as infectious agents.

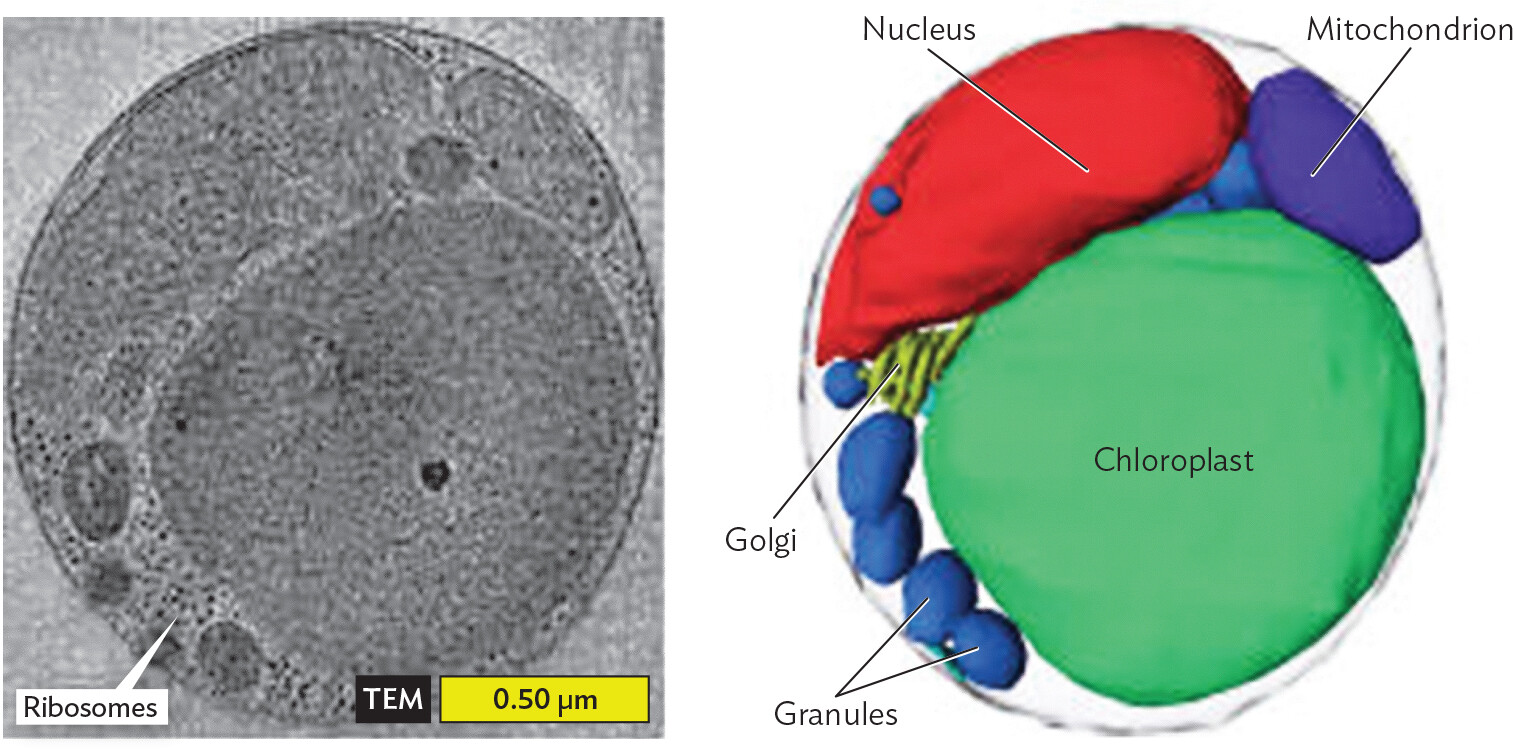

As presented in Chapter 5, the cells of all eukaryotes, whether multicellular or microbial, possess a nucleus and other key membranous organelles. Membranous organelles enable some microbial eukaryotes to grow to a million times larger than a bacterial cell. Yet others, particularly marine algae, have been downsized by evolution to less than 2 μm, comparable in size to Escherichia coli. Even so, tiny eukaryotes such as the alga Ostreococcus tauri (Figure 11.1) possess all the key organelles of a eukaryote. These organelles include the nucleus, containing linear chromosomes; mitochondria, the powerhouses of respiration; the endomembrane system and Golgi, for intracellular transport; and a chloroplast, for photosynthesis.

A micrograph and a 3 D tomograph of the eukaryote Ostreococcus Tauri and its organelles. The first part is the micrograph and the second part is the tomograph. Both show the same cell. In the micrograph, the organelle membranes are visible. The organelles have grainy interiors. In the tomograph, the organelles are clearly defined and labeled. From largest to smallest, the organelles inside the cell are the chloroplast, nucleus, mitochondrion, granules and ribosomes. The Golgi apparatus has a structure similar to stacked sheets and is only partially visible behind the chloroplast and the nucleus.

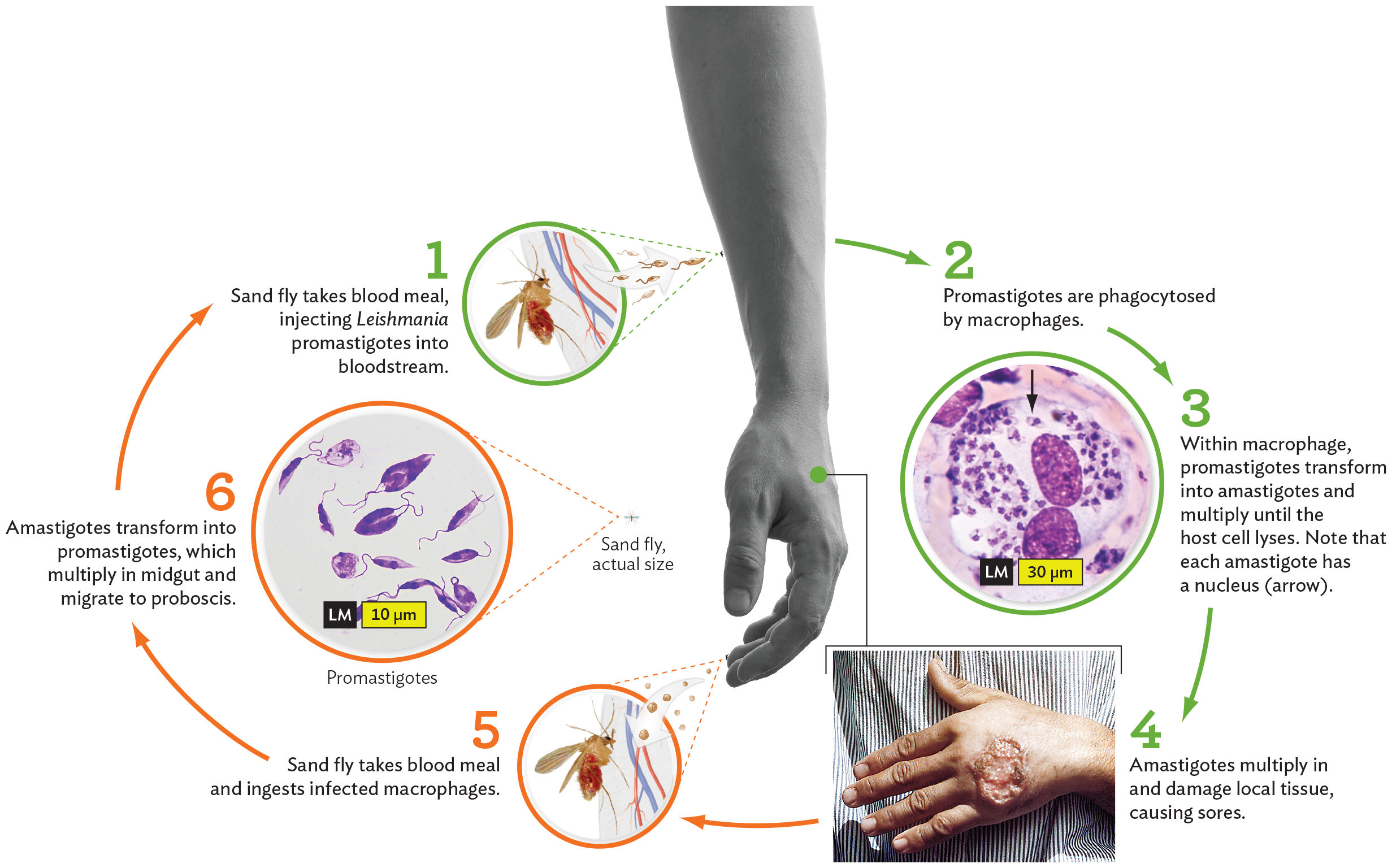

Some eukaryotes are parasites that cause diseases such as malaria and trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness). Leishmania is a protozoan that causes leishmaniasis, described in the chapter-opening case history. Parasitic protozoa often have complex life cycles, sometimes involving multiple hosts. In the life cycle of Leishmania, the promastigote, or flagellated form of the protozoan, is carried by a sand fly (Figure 11.2, step 1), which injects it into the skin of the host. In the bloodstream, the promastigotes are phagocytosed by macrophages (white blood cells), which attempt to destroy them (step 2). But the promastigotes survive within the macrophage and develop into amastigotes (unflagellated forms) that multiply intracellularly (step 3). The macrophage bursts, releasing amastigotes that multiply within various host tissues, causing sores (step 4). When another sand fly takes a blood meal (step 5), it ingests infected macrophages full of amastigotes. The amastigotes develop into promastigotes within the sand fly’s midgut (step 6). The promastigotes multiply and migrate to the proboscis, where they can be transmitted to the next host that the sand fly bites. Complex reproductive cycles are typical of infectious parasites and pose challenges for therapy.

A diagram of the stages in the lifecycle of the Leishmania parasite. The first stage shows a sand fly feeding on blood from a human hand, injecting the Leishmania parasites into the tubular blood vessels of the arm of the host. The caption reads, Sand fly takes a blood meal, injecting Leishmania promastigotes into the bloodstream. Next, the promastigotes are phagocytosed by macrophages. The text for the third stage reads, Within the macrophage, promastigotes transform into amastigotes and multiply until the host cell lyses. Note that each amastigote has a nucleus. A light micrograph shows the large oval shaped structure of a macrophage. It has two large purple circles within it, and many small circle shaped Leishmania parasites throughout its cytoplasm. The fourth stage shows a human hand with a wound that has irregular puffy and ridged borders. The caption reads, Amastigotes multiply in and damage local tissue, causing sores. The fifth stage shows a sand fly feeding on the blood from the tubular blood vessels of the host’s fingers, and indicates the Prescence of circular cells in the bloodstream. The caption reads, Sand fly takes a blood meal and ingests infected macrophages. The sixth stage shows a light micrograph. The micrograph shows promastigotes, each with elongated oval shaped body structures, one or two flagella, and the nucleus, a smaller darker structure near the center. An inset shows a sand fly that is the size of a dot compared to the human hand but carries numerous Leishmania parasites. The caption reads, Amastigotes transform into promastigotes, which multiply in the midgut and migrate to the proboscis. An arrowhead from the sixth stage moves to the first stage shows the continuation of the cycle.

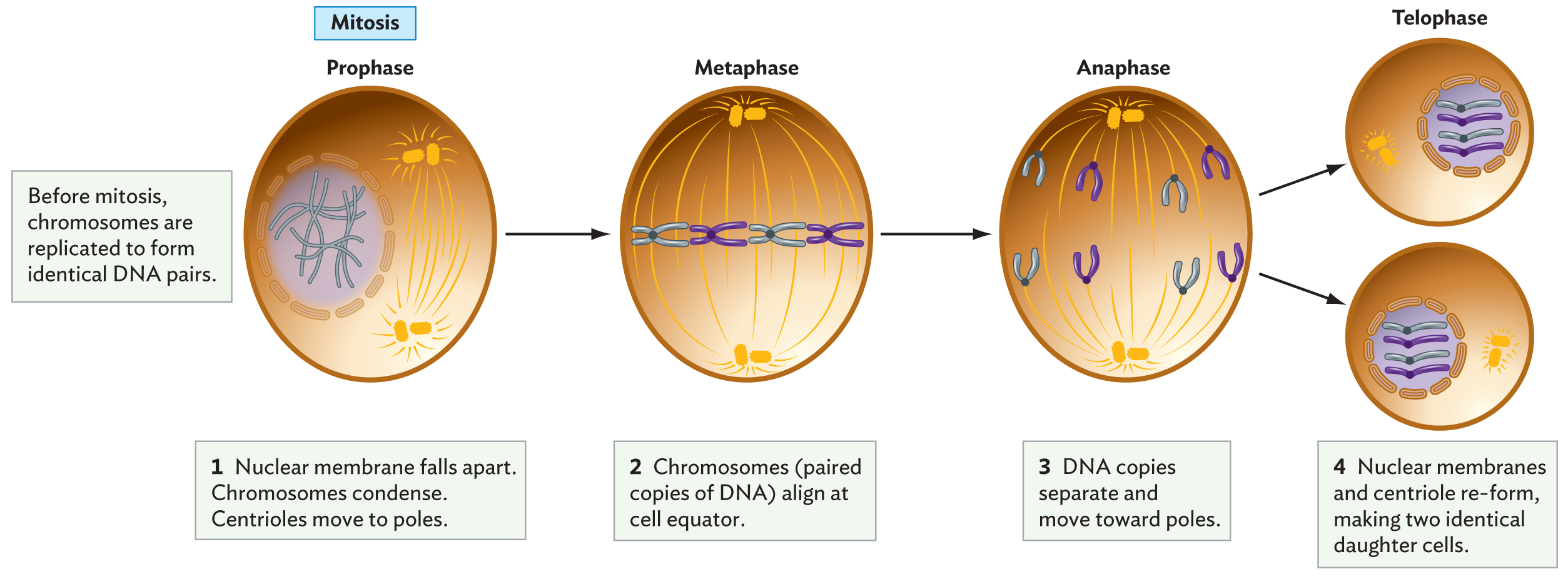

All eukaryotes have linear chromosomes that must divide by mitosis. The “ends” of linear chromosomes require special means of replication not required for most bacteria with their circular chromosomes. DNA replication occurs during a portion of interphase, the active state of the cell. Once DNA replication is complete, the cell halts most of its enzymatic activities and prepares for mitosis (Figure 11.3A). Mitosis is the process of segregating the two copies of all chromosomes evenly into the daughter cells. The process ensures that each daughter cell receives a full set of daughter chromosomes.

A diagram of mitosis. There are four phases in mitosis, prophase, metaphase, anaphase and telophase. Mitosis results in two identical daughter cells. A caption reads, before mitosis, chromosomes are replicated to form identical D N A pairs. Step 1, nuclear membrane falls apart. Chromosomes condense. Centrioles move to poles. There is an illustration of a cell during prophase. Chromosomes within the nucleus are condensing into x shapes. The membrane around the nucleus has fragmented. In the cytoplasm, centrioles are seen drifting to opposite poles. A caption reads, step 2, chromosomes, or paired copies of D N A, align at the cell equator. There is an illustration of a cell during metaphase. 4 X shaped chromosomes are lined up horizontally across the cell. The centromeres are located in opposite poles of the cell. Spindles from the centromeres extend toward the line of chromosomes. A caption reads, step 3, D N A copies separate and move toward poles. There is an illustration of a cell during anaphase. The four chromosomes have been split into eight halves. A set of four is pulled toward either centromere by spindle fibers. A caption reads, step 4, nuclear membranes and centriole re form, making two identical daughter cells. There is an illustration of two cells during telophase. Each cell has a nucleus containing four chromosomes and a centromere. The nucleus is enclosed within a complete nuclear membrane. There is an equal mix of the chromosome types in each cell.

A diagram of meiosis. There are two phases in meiosis, meiosis 1 and meiosis 2. Meiosis results in four unique gamete cells. A caption reads, before meiosis, chromosomes are replicated to form identical D N A pairs. A cell is shown during meiosis 1. The cell contains a nucleus with condensing chromosomes and a fragmenting nuclear membrane. In the cytoplasm, centromeres are drifting to opposite poles of the cell. In the next step, chromosome tetrads are organized in a horizontal line through the center of the cell. Spindle fibers extend toward the tetrads from the centromeres at both poles. In the next step, tetrads are split and chromosomes are pulled to opposite centromeres. The cell begins to divide into two cells. The captions for meiosis 1 read, step 1, nuclear membrane falls apart and centrioles move to poles. Duplicated chromosomes pair with homologs, forming tetrads. Arms cross over. Step 2, tetrads, or pairs of homologs, align at cell equator. Step 3, homologs separate and move toward poles, with D N A copies still paired. There is an illustration of two daughter cells at the start of meiosis 2. In each cell, four chromosome arms are aligned in the middle of the cell. Two arms are pulled toward one centromere and two arms are pulled toward the other centromere. In the next step, each daughter cell has generated two more cells. There are four cells total. Each cell contains a nucleus with unique chromosomes enclosed in a nuclear membrane. Each cell also has a centromere. The captions for meiosis 2 read, step 4, daughter cells form but enter a second round of division similar to mitosis. Step 5, four unique gamete cells form with one copy of each chromosome, recombined from the parent.

In most cases, mitosis involves four phases:

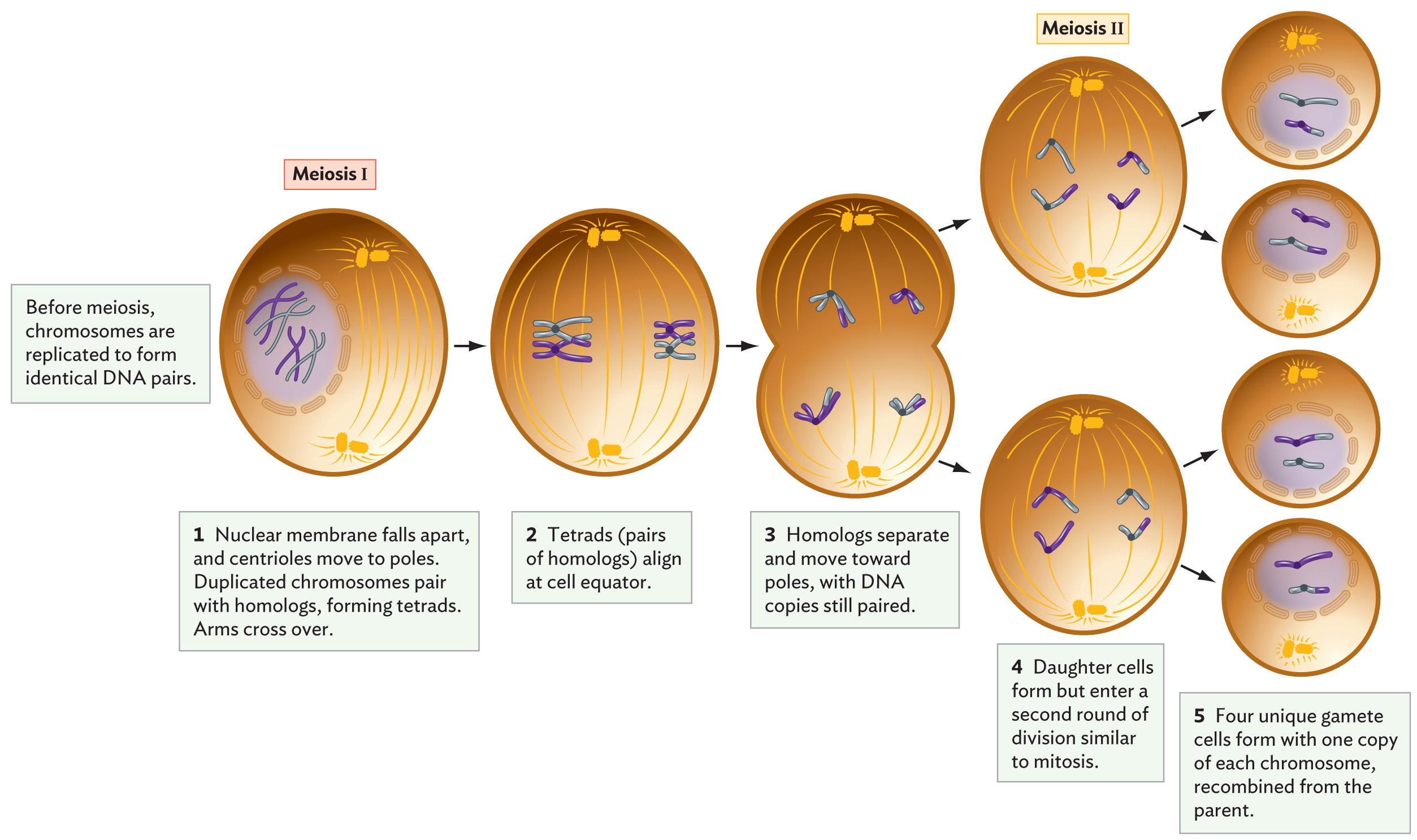

Many eukaryotic microbes, such as yeasts, can proliferate indefinitely by mitosis, a process called asexual reproduction or vegetative reproduction. But most eukaryotes, single-celled or multicellular, also have the option of sexual reproduction. Sexual reproduction requires the reassortment of genetic material from different chromosomes. A sexual life cycle alternates between cells that are diploid (2n, containing two copies of each chromosome) and sex cells that are haploid (n, containing a single copy of each chromosome). Two of the haploid sex cells (called gametes) can join each other by fertilization to regenerate a diploid cell (called a zygote). The diploid thus possesses two homologs of each chromosome—that is, two versions of the same chromosome from two different parents.

The process of gamete formation requires a special modification of mitotic cell division called meiosis (Figure 11.3B). Meiosis includes two cell divisions: meiosis I and meiosis II. Like mitosis, meiosis I must be preceded by replication of all chromosomes (during interphase). So a diploid (2n) cell temporarily has four copies of each DNA homolog. In meiosis, unlike mitosis, prophase I requires that each replicated pair line up with its homolog, the homologous chromosome inherited from the other parent. Now the aligned homologs exchange portions of their DNA. This genetic exchange reassorts the gene versions from the two parents and increases genetic diversity in the next generation.

In meiosis I, the paired homologs separate during metaphase I and anaphase I. A short telophase occurs, in which each daughter cell now has a total of 2n DNA helices, but as n pairs containing a chromosome from each parent. The chromosome pairs then separate during meiosis II, which includes prophase II, metaphase II, anaphase II, and telophase II. The result is four haploid (n) cells, as seen in Figure 11.3B.

For many microbes, the haploid forms may undergo asexual (vegetative) reproduction. At some point, the haploid forms may develop into specialized cells that reunite through fertilization, restoring a diploid form (the zygote). The asexual reproduction of both haploid and diploid forms leads to a life cycle known as alternation of generations.

What is the advantage of alternation between haploid (n) and diploid (2n) forms? Consider a protozoan parasite that grows within a human host. The haploid form of the parasite requires fewer resources and generates fewer varieties of coat proteins that might activate the host’s immune system. But the diploid form generates novel combinations of genes that may provide an advantage when the environment changes or when the parasite enters a new host. Thus, most eukaryotic microbes maintain the option of a sexual cycle that alternates between haploid and diploid. In some cases, one form exists only briefly; for example, the malarial parasite proliferates mainly as a haploid but undergoes a brief cycle of fertilization and meiosis within the insect vector.

Microbial eukaryotes are classified traditionally as fungi, protozoa, and algae. For most of human history, life was understood in terms of multicellular eukaryotes. There were animals (creatures that move to obtain food) and plants (rooted organisms that grow in sunlight). Fungi (singular, fungus) lack photosynthesis yet were considered a form of plant because they grow on the soil or other substrate. As a result, mycology, the study of fungi, was often included with botany, the study of plants. Later, microscopists came to recognize microscopic forms of fungi such as hyphae (filaments of cells) and yeasts (single cells); thus, fungi were studied also by microbiologists. Surprisingly, however, fungi show close genetic relatedness to multicellular animals.

Other microscopic life forms, such as amebas and paramecia, are motile and appear more like microscopic animals. Motile organisms were called protozoa (singular, protozoan), meaning “first animals,” although they are more distantly related to animals than fungi are. Microscopic life forms containing green chloroplasts were called algae (singular, alga) and were thought of as primitive plants. But some protozoa turned out to have chloroplasts, and some algae turned out to be motile with flagella. Microbiologists refer to algae and protozoa collectively as protists.

How do microbial eukaryotes relate to multicellular animals and plants? Plants show close genetic relationship with the “primary algae,” green algae that evolved from a common chloroplast-bearing ancestor. Animals, however, are most closely related to fungi, based on comparing their DNA sequences. DNA sequence analysis shows that several different groups of protists are more different from each other—and from animals—than animals are from fungi.

Major kinds of microbial eukaryotes are summarized in Table 11.1. Although all these groups include microbial forms, they also include species that can be observed by the unaided eye (such as giant amebas) as well as multicellular forms (such as mushrooms and kelps). Thus, the term “microbe” is a working description but does not define a strict category of life.

Major groups of microbial eukaryotes include the following:

These groups are considered “true” microbes, although they include large macroscopic forms, such as mushrooms (fungal fruiting bodies) and sheets of kelp (algae). Certain other multicellular parasites are not considered microbes even though they may be too small to see, such as mites and worms. These invertebrate animals have fully differentiated organ systems, sometimes comparable in complexity to those of vertebrates. Nevertheless, the dynamics of transmission and infection of invertebrate parasites parallel those of microbial pathogens. Therefore, invertebrate parasites are often covered by health professionals under the category of “eukaryotic microbiology.” In particular:

Worms and arthropods are a major source of morbidity and mortality worldwide. A quarter of the world’s population is parasitized by worms, including at least 10% of people in the United States. The presence of worms causes nutritional impairment and developmental delays. The horror of infection by worms and arthropods inspired the classic science fiction film Alien, which depicts an intelligent extraterrestrial parasite.

SECTION SUMMARY