SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe the different types of viral structure, and give an example of each.

- Explain the significance of viral genome size.

- Describe the nature of viroids and prions.

- Explain why viruses evolve so fast.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

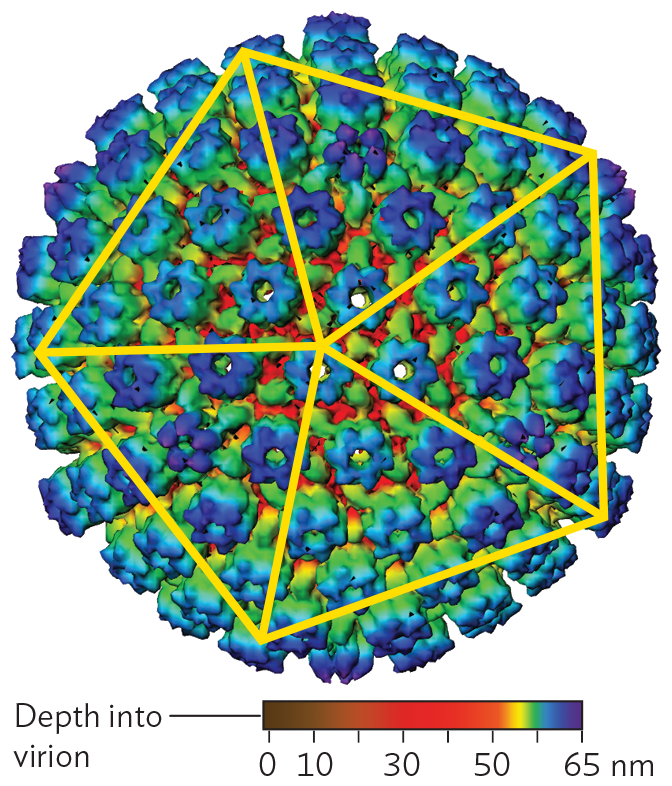

What different kinds of structure can a virus have? An important basis for classification of viruses is their capsid, the protein package that encloses their genome. Many viruses have a capsid with surprisingly beautiful radial symmetry, such as that of herpesvirus (Figure 12.4). Other kinds of virus have a capsid that is filamentous, or one that is complex with a tail structure. Still other kinds of viruses, such as poxviruses, are amorphous (lacking symmetry).

A cryo E M model of the Icosahedral capsid of herpes simplex virus 1. The model shows the large spherical-shaped structure. Peg shaped proteins cover the outer surface in a uniform fashion. A pentagon is drawn over the sphere with five lines connecting each vertex to the center of the pentagon.

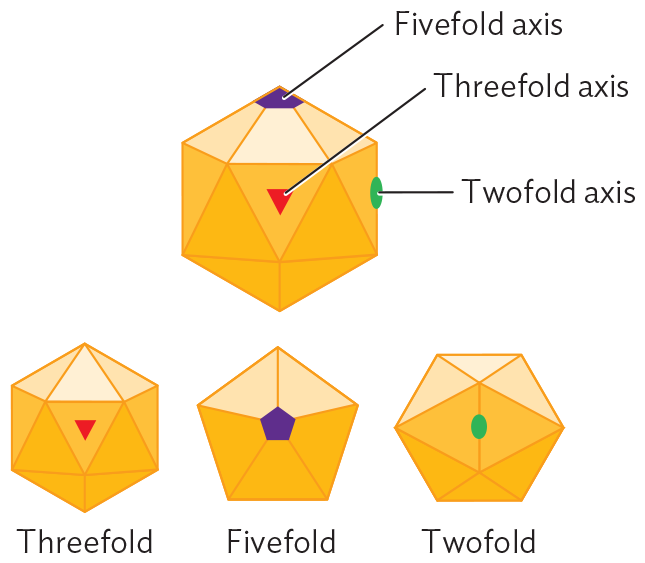

A diagram explaining icosahedral symmetry. The illustration shows a 3 D hexagon structure made of triangle faces. The five fold axis is a vertex of the triangles. The threefold axis is in the center of a triangle. The twofold axis is on the edge of two triangles. Illustrations show the icosahedral shape rotated to view the structure from above each axis of symmetry.

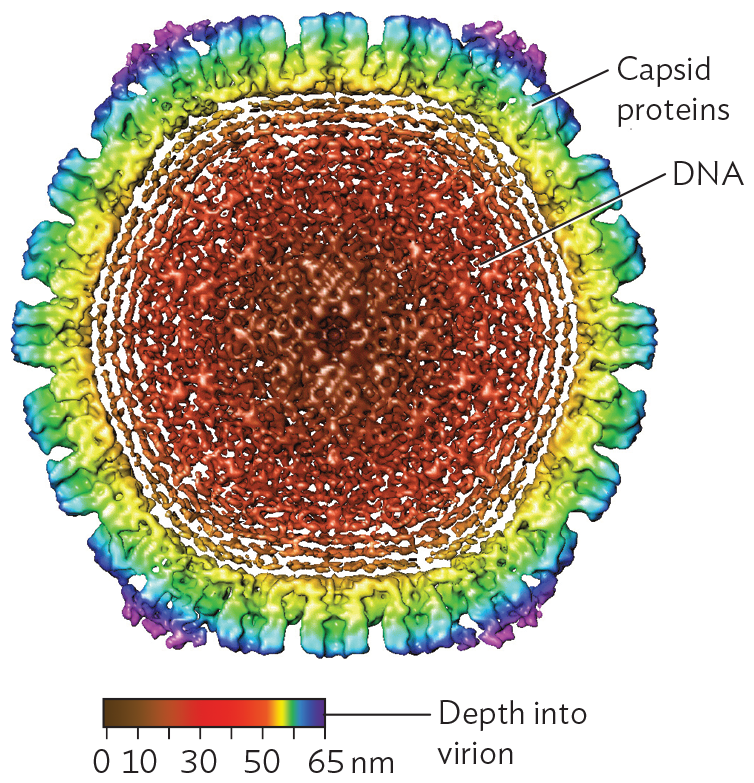

A cryo E M model of spooled D N A within an icosahedral capsid. The model shows a cross sectional view of the roughly spherical capsid. Rounded points of the icosahedral shape are seen with this view. The outer surface of the capsid is covered in peg shaped capsid proteins. In the center of the capsid, there are tightly packed concentric rings of D N A.

The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) devised a classification scheme that includes factors such as capsid form (icosahedral or filamentous), envelope (present or absent), and host range.

Icosahedral capsids. Many viral capsids show radial symmetry, like a crystalline object. The advantage of symmetry is that it forms a package out of repeating protein units generated by a small number of genes. The smaller the viral genome, the more genome copies can be synthesized from the host cell’s limited supply of nucleotides.

The form of a radially symmetrical virion is based on an icosahedron, a polyhedron with 20 identical triangular faces. An example of an icosahedral capsid is that of herpes simplex virus (Figure 12.4A). Each triangular face of the capsid is determined by the same genes encoding the same protein subunits. No matter what the pattern of subunits in the triangle is, the structure overall exhibits rotational symmetry characteristic of an icosahedron (Figure 12.4B). Within the icosahedral capsid, the herpesvirus genome (composed of double-stranded DNA) is spooled tightly (Figure 12.4C), the DNA packed under high pressure. When the herpes capsid enters the cell, it is transported to a nuclear pore complex, where the pressure is released. The pressure release drives viral DNA into the host nucleus.

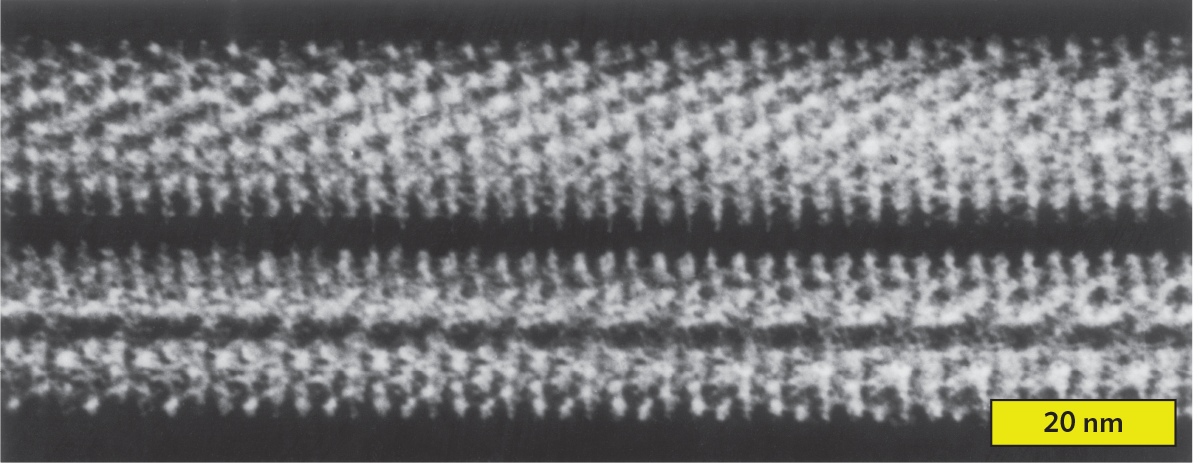

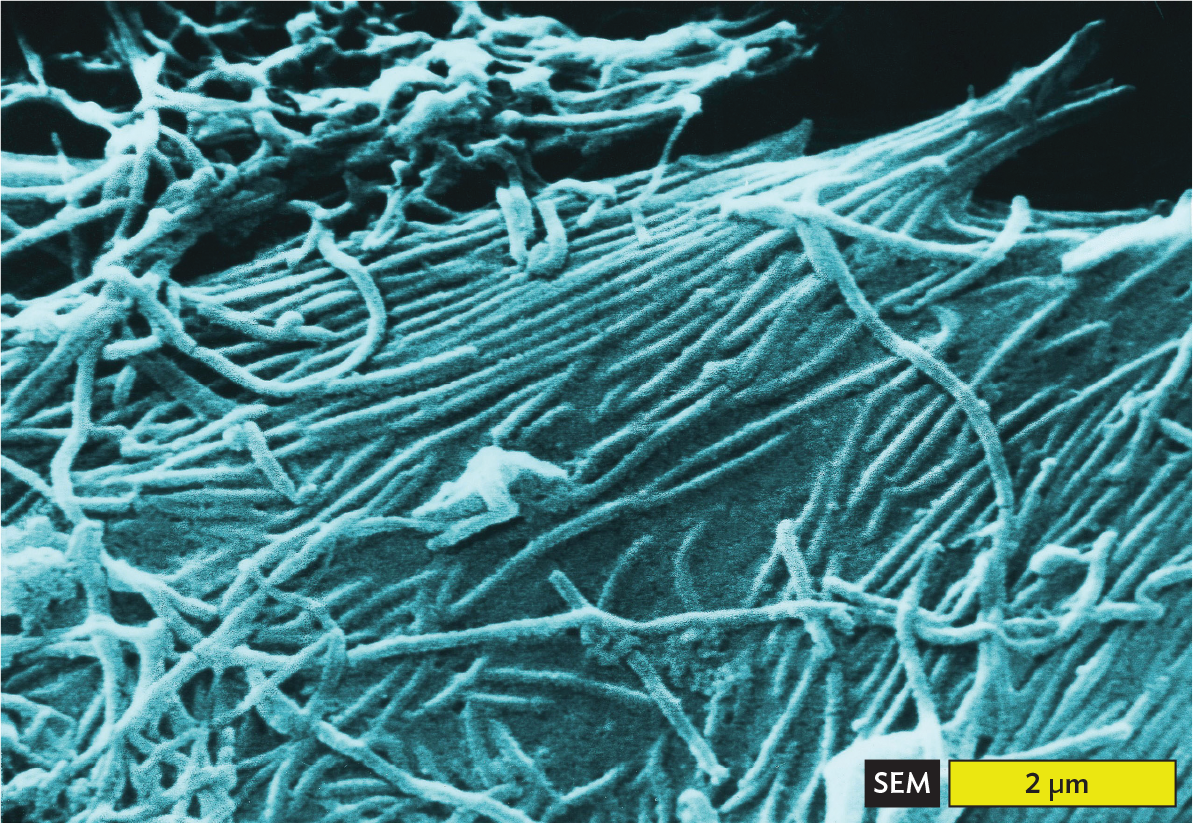

Filamentous viruses. Filamentous viruses include tobacco mosaic virus (Figure 12.5A) as well as animal viruses such as Ebola virus, which causes a swiftly fatal disease of humans and related primates (Figure 12.5B). Some bacteriophages are filamentous; for example, the filamentous phage CTXφ integrates its sequence into the genome of Vibrio cholerae, where it carries the genes for the deadly cholera toxin (discussed in Chapter 4).

An x ray crystallography reconstruction of the helical filament of tobacco mosaic virus. There are two thick parallel horizontal lines. They are white on a black background, and seem to be made up of many dot like particles. The dots are lined up to show rows that run diagonally to the length of the filament line. The width of each filament is approximately 20 nanometers.

A scanning electron micrograph of Ebola virions. The micrograph shows long thin tubular structures tangled with each other. They also appear to be embedded in a smooth stretching surface. The width of each virion is approximately 0.2 micrometers. Each virion is at least 2 micrometers long.

Filamentous viruses show helical symmetry. The pattern of capsid monomers forms a helical tube around the genome, which is wound helically within the tube (see Figure 12.5A). The length of the helical capsid may extend up to 50 times its width, generating a flexible filament. Unlike the icosahedral capsid, which has a fixed size, the helical capsid can vary in length to accommodate different lengths of nucleic acid. This variable length is convenient for genetic engineering vectors (viruses with genomes artificially recombined to carry genes into cells).

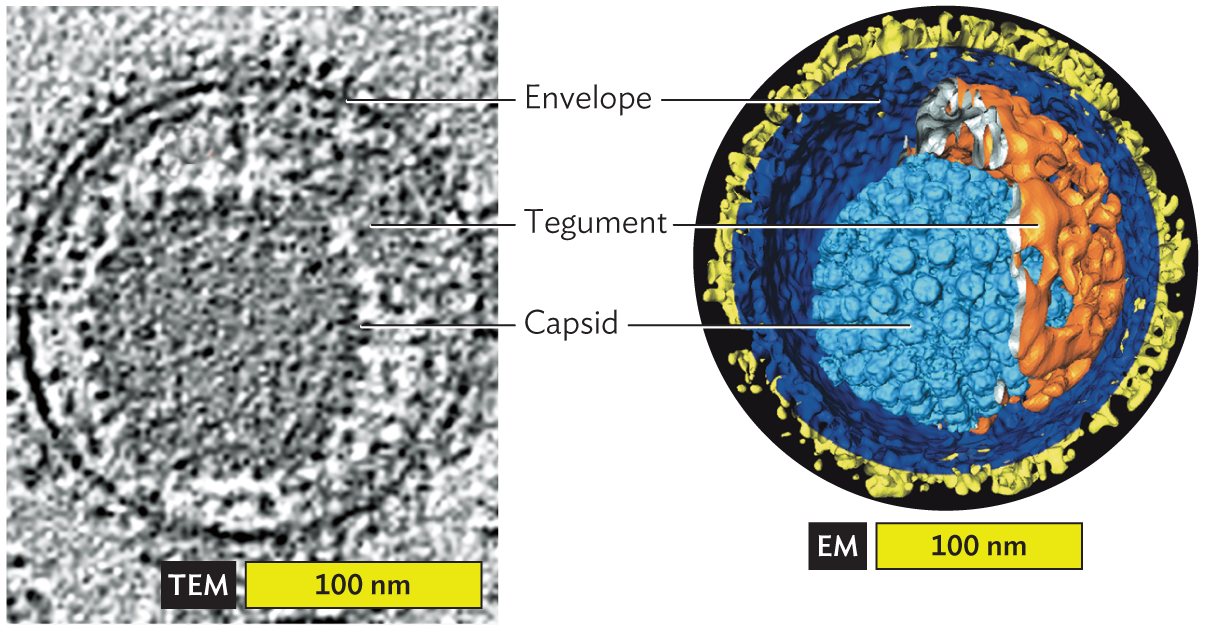

Envelope. Some viruses, such as poliovirus and papillomavirus, have only a protein capsid. Other viruses, such as herpesviruses and coronaviruses, also have an envelope derived from the host nuclear or endoplasmic reticulum membrane (Figure 12.6). The envelope of a herpesvirus bristles with virus-encoded spike proteins that plug the membrane onto the capsid. The spike proteins enable the virus to attach and infect the next host cell.

A micrograph and an associated cryo E M model identify envelope and tegument structures surrounding the Herpes virus capsid. The first part is the micrograph showing the envelope and tegument proteins surrounding the capsid. The second part is the cryo E M model, showing the structures of the same capsid in greater detail. The capsid is an icosahedral shape set slightly off center within the spherical envelope. Tegument proteins fill the space between the capsid and the envelope.

A. Section showing envelope and tegument proteins surrounding the capsid (cryo-TEM).B. Cutaway reconstruction: spike envelope glycoproteins (yellow), envelope membrane (dark blue), tegument proteins (orange), and capsid proteins (light blue; cryo-EM tomography).

Between the envelope and the capsid may be additional proteins called tegument (see Figure 12.6). Tegument proteins are expressed during infection of a host cell and then packaged in the virion during envelope formation. Both viral and host proteins may be packaged. As the virus enters a new host cell, the viral envelope fuses with the host cell membrane in a way that opens the viral contents to the cytoplasm. The tegument proteins are released in the cytoplasm, where they help viral replication.

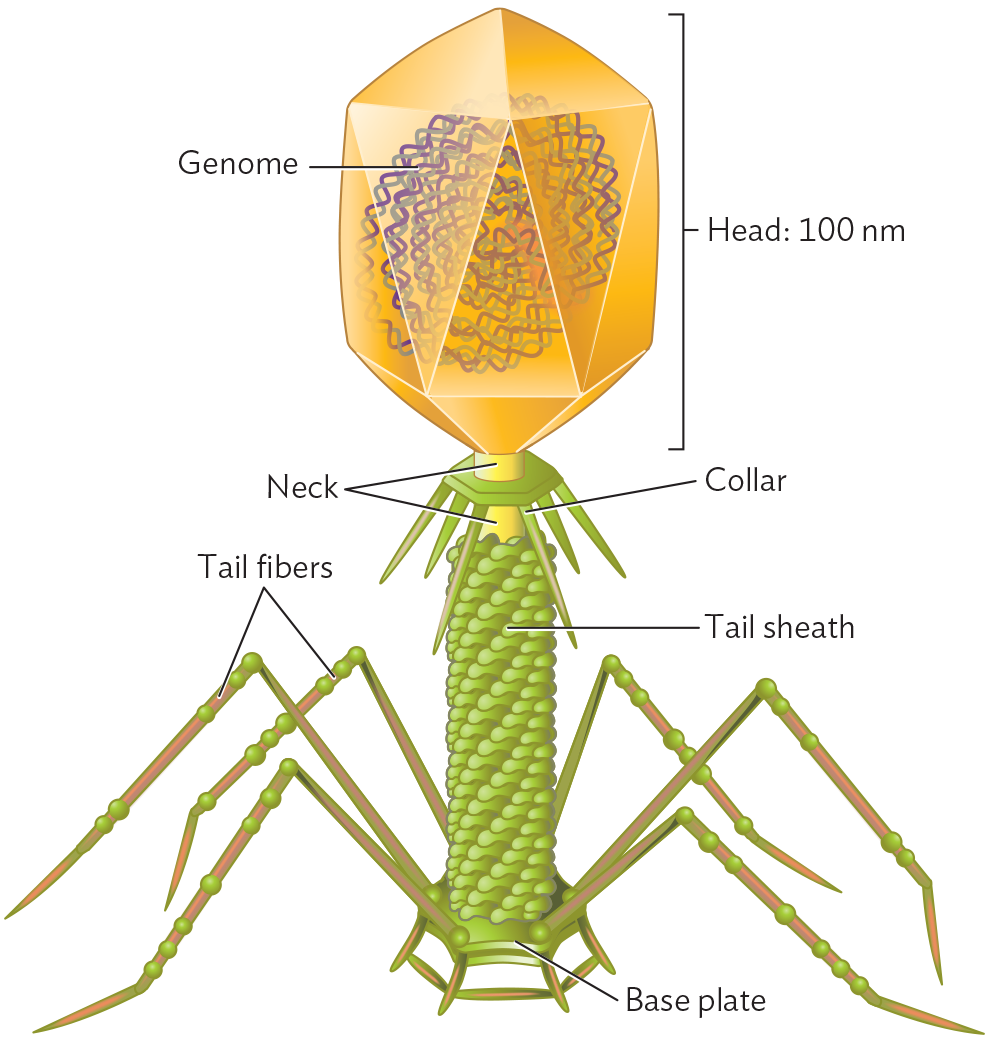

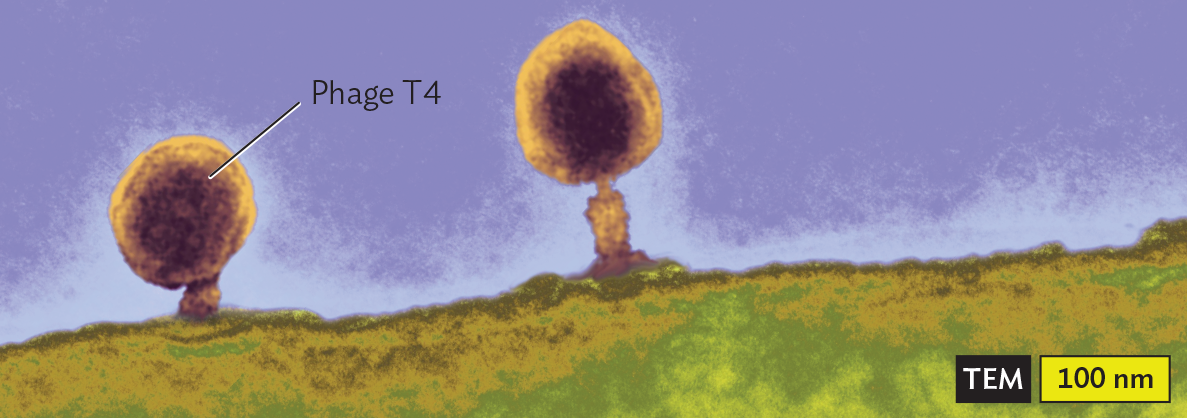

Tailed bacteriophages. Some bacteriophages have complex multipart structures. In a tailed phage, the icosahedral protein package, called the “head,” is attached to an elaborate delivery device. For example, bacteriophage T4 (Figure 12.7) has an elongated icosahedral head containing the pressure-packed DNA, attached to a helical “neck” that channels the nucleic acid into the host cell. The neck is surrounded by the tail sheath, with six jointed tail fibers that attach the bacteriophage to the host cell surface. Within the tail, an “injector” penetrates the host cell envelope, and the release of pressure within the head propels the DNA into the host cytoplasm.

An illustration of the Bacteriophage T 4 Capsid. The capsid consists of an icosahedral head structure attached to a tail structure. The head has a length of 100 nanometers. A double stranded D N A genome is packaged within the head structure. The thick tubular structure leading down from the head is the neck. Around the neck is a ring with spikes which is the collar. Below the collar, a spiral formed by small circles around the neck is the tail sheath. The tail ends in a base plate. Attached to the baseplate are long, thin tubes in the form of inverted V-shaped structures that have small spheres on them. These are the tail fibers.

A transmission electron micrograph of the Bacteriophage T4 Capsid. There is a rod shaped bacterium with a darkly staining outer membrane. The interior of the cell is grainy and marbled. The cell is about 4500 nanometers long and 900 nanometers wide. Phage T 4s are attached to the outer surfaces of the cell. Each phage T 4 has an icosahedral head structure attached to a tubular tail structure. The phages attach to the cell by the base plate of the tail structures. A darkly staining genome is visible within the head structures of the phages.

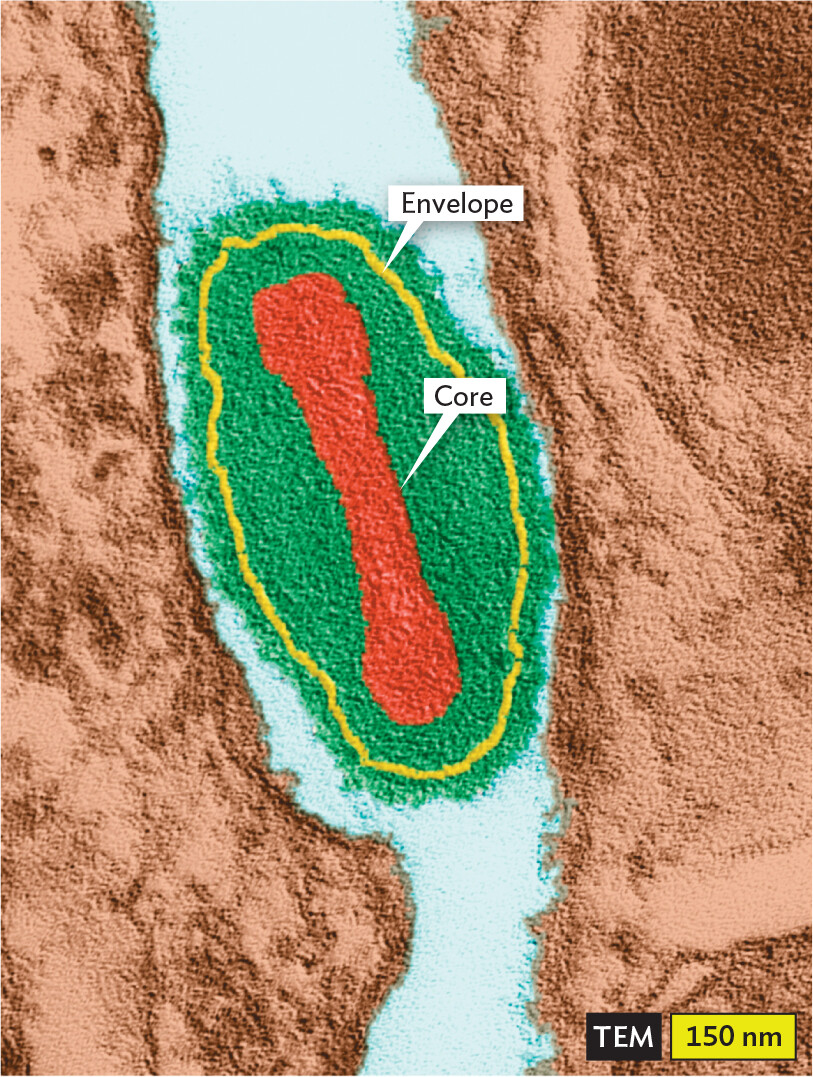

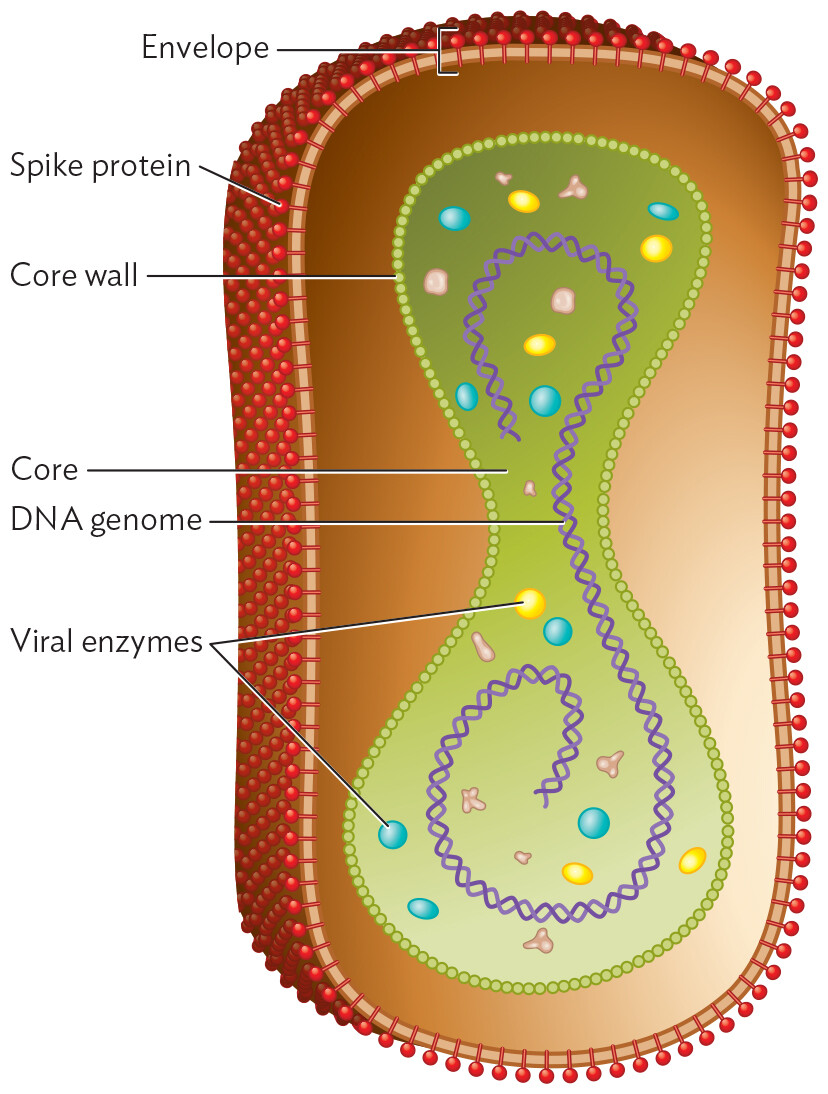

Amorphous or complex viruses. Some viruses have no symmetrical form (Figure 12.8). Poxviruses are large asymmetrical viruses. The size of vaccinia virus (360 nm) approaches that of some bacteria. Vaccinia virus, also known as “cowpox virus,” was the virus used by Edward Jenner and others around the year 1800 to make the first vaccine against smallpox (caused by the closely related variola virus). Today, vaccinia is used as a genetic vector to develop vaccines against many animal diseases.

A transmission electron micrograph of a Vaccinia Virus particle. The particle is oval shaped. It has a centrally located, elongated ovoid core. A thin outer envelope encloses the virus particle. The particle is about 300 nanometers wide and 600 nanometers long.

An illustration of the structure of Vaccinia Virus. The illustration shows a cross section of a pill shaped particle. The outer layer is the envelope. The envelope is covered in tubular spines which are spike proteins. An inner elongated ovoid structure is the core. The border of the core is made of spheres which are the core wall. There is a double-helical structure in the core, which is the D N A genome. In the core there are also small circles which are viral enzymes.

The DNA genome of a poxvirus is contained by a flexible “core wall” that also encloses a large number of enzymes and accessory proteins, similar to the contents of a cell’s cytoplasm. The double-stranded DNA genome resembles that of a cell, except that it is stabilized by covalent connection of its two strands at each end. The core is enclosed loosely by a viral envelope studded with spike proteins.

How do viruses arrange their genetic information? The genomes of viruses, especially RNA viruses, can be surprisingly small, and the ability of such small entities to take over cells is remarkable. Viruses evolve rapidly, enabling them to evade host defenses and even to “jump” into new host species.

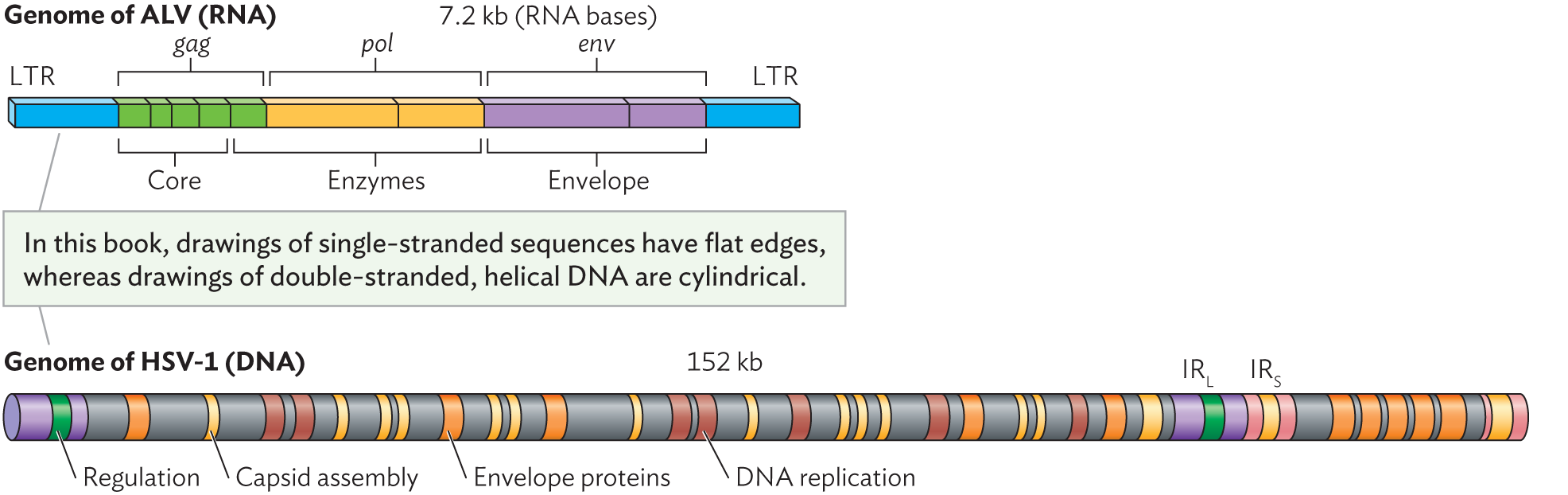

The genome of an RNA virus can be as small as three genes. Figure 12.9A depicts the genome of avian leukosis virus (ALV), a well-studied retrovirus that causes lymphoma in chickens. The ALV genome has three protein-encoding genes: gag, pol, and env. Retroviruses have small genomes whose synthesis consumes minimal resources, thus maximizing the number of virions that can be made from an infected cell.

Two illustrations of simple viral genomes. Text between the illustrations reads, in this book, drawings of single-stranded sequences have flat edges, whereas drawings of double stranded, helical D N A are cylindrical. End text. The first illustration shows the genome of A L V, which is a single stranded R N A genome. It is 7.2 kilobases long and consists of long terminal repeats, core genes, enzyme genes, and envelope genes. The second illustration shows the genome of H S V 1, which is a double stranded D N A genome. It is 152 kilobases long and consists of regulation genes, capsid assembly genes, envelope proteins, and D N A replication genes. It also has long and short inverted repeat sequences.

A. The single-stranded RNA genome of avian leukosis virus, a retrovirus. Three genes (gag, pol, and env) encode polypeptides that are eventually cleaved to form a total of nine functional products. LTR = long terminal repeat; blue sections indicate noncoding RNA.

B. The double-stranded DNA genome of herpes simplex virus (HSV) spans 152,000 base pairs encoding more than 70 gene products. The types of products encoded are shown by color: regulation (green), capsid assembly (yellow), envelope proteins (orange), and DNA replication (brown). IRL and IRS are, respectively, long and short inverted-repeat sequences.

Other kinds of viral genomes are large, approaching the size of cellular genomes. Double-stranded DNA viruses have especially large genomes, encoding numerous enzymes and regulatory proteins similar to those of cells. For example, the genome of herpes simplex virus 1, a cause of cold sores and genital herpes, spans 152 kilobases and encodes more than 70 gene products (Figure 12.9B). These herpesvirus products include capsid and envelope proteins, DNA replication proteins, and accessory proteins that manage viral replication or interact with host immune cells. Other herpes genes encode latency proteins that can maintain the virus in a latent state within the host cell. Overall, herpes genomes have evolved to be highly regulated, with numerous extra products that have small but important effects on viral replication and host interaction. Some giant viruses such as Pandoravirus have genomes larger than 3 million base pairs.

Some infectious agents are so limited in content that they cannot even be considered viruses. Viroids are virus-like infectious agents in which an RNA genome is itself the entire infectious particle; there is no protective capsid. Most viroids infect plants, including many kinds of fruits and vegetables. For example, citrus viroids cause economic losses in the citrus industry. The viroid typically consists of a circular, single-stranded molecule of RNA that doubles back on itself to form base pairs interrupted by short, unpaired loops.

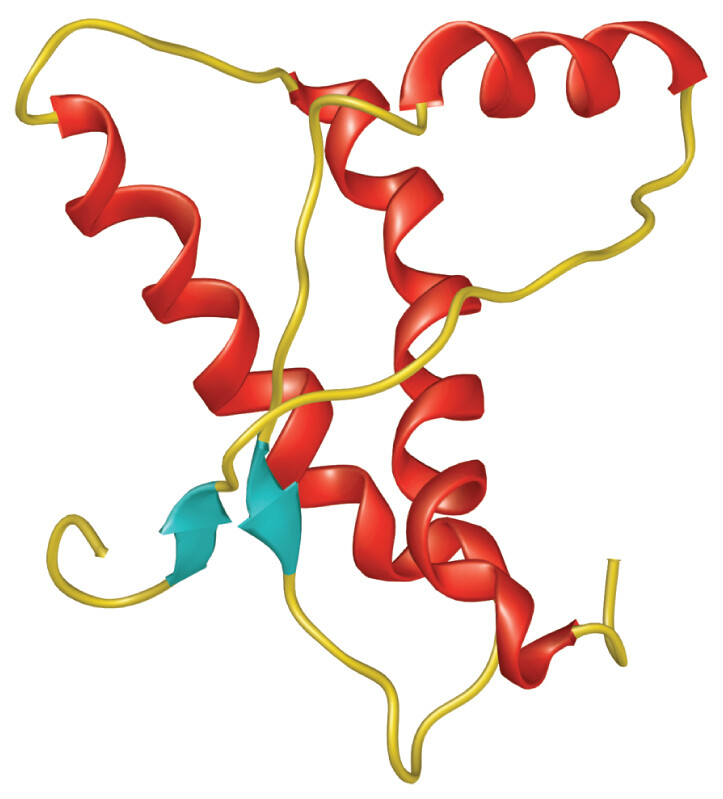

Yet another class of infectious agents has no nucleic acid at all. These agents, known as prions, are aberrant (wrongly folded) proteins arising out of a preexisting cell. Prions gained notoriety when they were implicated in “mad cow disease,” a brain condition in cattle that, after being transmitted to humans who consumed beef from diseased cows, caused human brain disease. The bovine prions resembled a human protein closely enough to cause misfolding of native human proteins and thus damage the brain cells. The pathology resembled that of the inherited brain condition Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Other diseases caused by prion transmission include scrapie, a brain disease of sheep; and kuru, a degenerative brain disease formerly endemic among the Fore people of New Guinea. In the early twentieth century, the Fore people customarily consumed the brains of deceased relatives. When this practice stopped, the disease kuru disappeared.

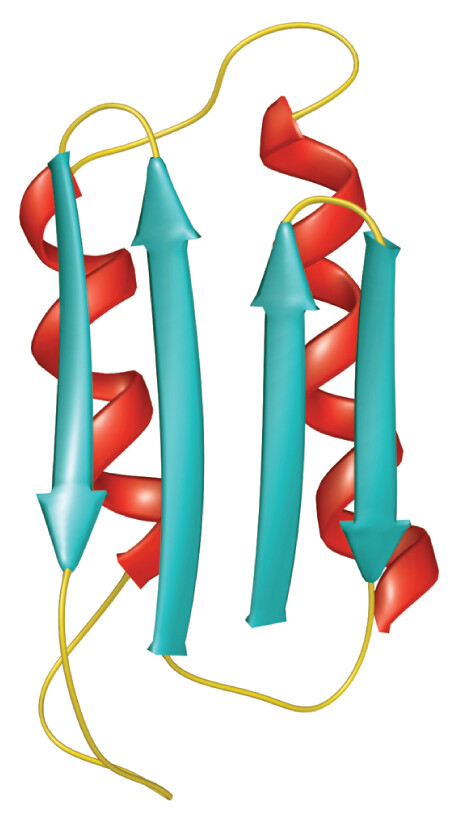

The prion associated with these brain diseases is an abnormal form of a normally occurring brain cell protein called PrPC (Figure 12.10). The prion form, called PrPSc, acts by binding to normally folded proteins of the same class. When it binds, the prion alters the protein’s normal conformation to that of the prion. The misfolded protein then alters the conformation of other normal subunits, forming harmful aggregates and ultimately killing the cell. In the brain, prion-induced cell death leads to tissue deterioration and dementia (discussed in Chapter 24).

An illustrated model of the conformation of a normal protein. The protein is loosely folded. It consists of thin strands, short sheet structures, and long alpha helices. There is empty space between the different helices of the protein, giving it a loose and slightly disorganized appearance.

An illustrated model of the conformation of an abnormally folded protein, or prion. The protein is tightly folded. It consists of thin strands, long parallel sheets, and compact alpha helices. The structures appear highly compact and organized relative to the normal conformation.

Prion diseases can be initiated by infection with an aberrant protein. More rarely, the cascade of protein misfolding can start with the spontaneous misfolding of an endogenous host protein. The chance of spontaneous unfolding is greatly increased in individuals who inherit certain gene variants that encode the protein; thus, spontaneous prion diseases can be inherited genetically. Overall, prion diseases are unique in that they can be transmitted by an infective protein instead of by DNA or RNA, and they propagate conformational change of existing molecules without actually synthesizing new infective molecules.

Like cellular organisms, viruses evolve through genome change and natural selection (see Section 9.3). Their small genome size and small number of parts enable viruses to mutate tenfold or a hundredfold faster than their host cells. Rapid mutation and evolution of a virus leads to antigenic drift, the accumulation of random mutations that lead to viruses whose mutant proteins are no longer recognized by host antibodies. Antigenic drift generates new strains of viruses that cause serious disease; for example, antigenic drift continually generates new influenza strains requiring repeated immunization.

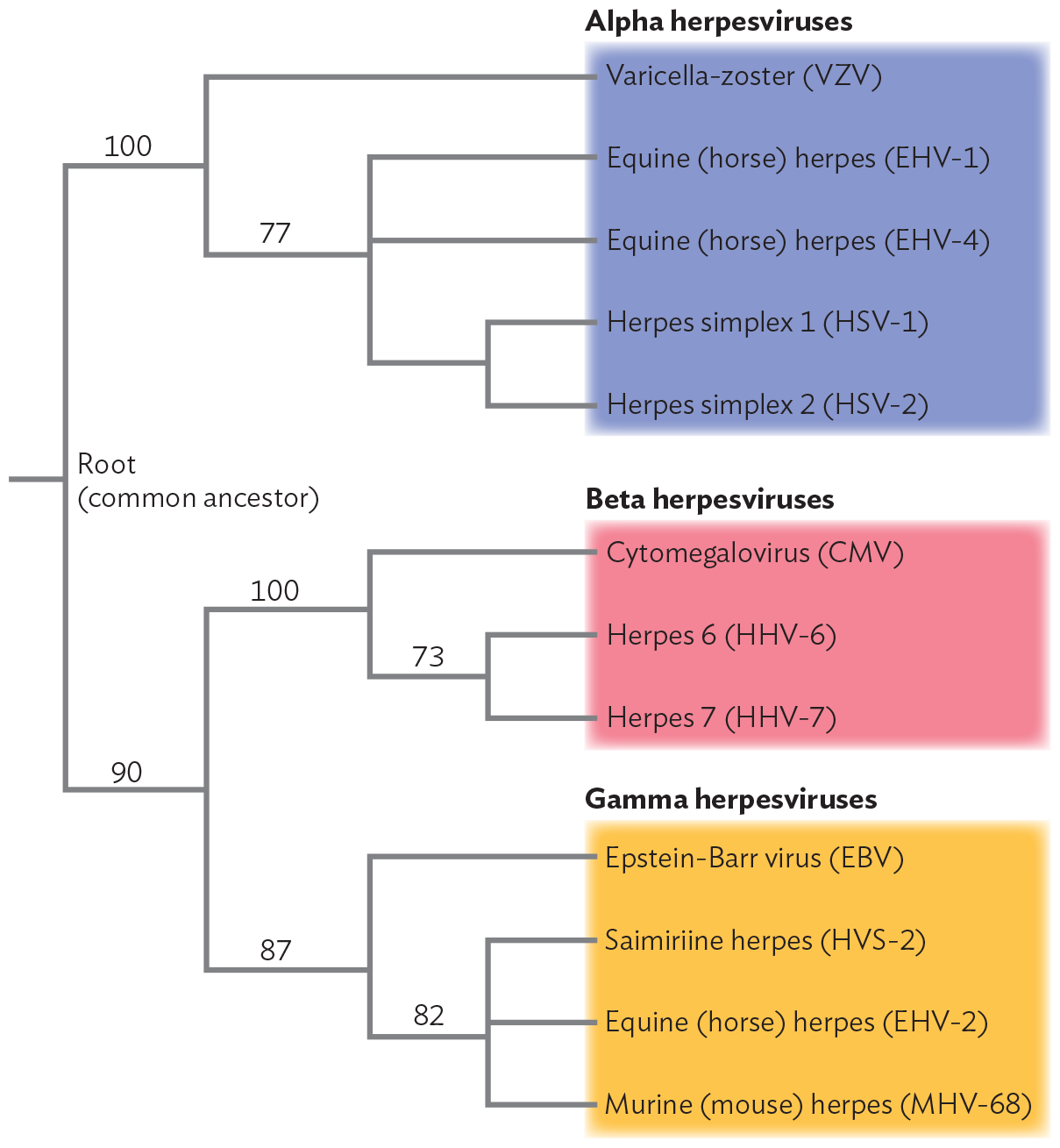

Over extended time, viral evolution generates new kinds of viruses that cause different diseases in different hosts. Figure 12.11 shows a phylogeny for herpesviruses, an ancient group of viruses infecting many animals. We see that over time, different diseases evolve, infecting the same or different species. Members of the herpesvirus family cause several important human diseases, including chickenpox (varicella-zoster virus), cold sores and genital lesions (herpes simplex 1 and 2), birth defects (cytomegalovirus), infectious mononucleosis (Epstein-Barr virus), and Kaposi’s sarcoma (human herpesvirus 8, not shown).

A diagram of the phylogenetic tree of Herpesvirus genomes. The schematic shows a phylogenetic tree with the root as an unnamed common ancestor. The root divides into two major branches labeled 100 and 90. The branch labeled 100 further branches into several clusters of Alpha herpes viruses. The first cluster shows Varicella-zoster virus, abbreviated V Z V. The second cluster forms a branch labeled 77. 77 branches into several clusters, Equine or horse herpes E H V 1, Equine herpes E H V 4, Herpes simplex 1, abbreviated H S V 1, and Herpes simplex 2, abbreviated H S V 2. Going back to the root, the other initial branch labeled 90 forms two branches labeled 100 and 87. The branch labeled 100 further branches into several clusters labeled Beta herpesviruses. The beta herpes viruses include cytomegalovirus, abbreviated C M V, herpes 6, abbreviated H H V 6, and herpes 7, abbreviated H H V 7. The branch labeled 87 further branches into several clusters labeled gamma herpesviruses. The gamma herpes viruses include Epstein-Barr virus, abbreviated E B V, Saimiriine herpes H V S 2, Equine herpes virus E H V 2, and Murine or mouse herpes M H V 68.

In general, viruses evolve at different levels, all of which are significant for medicine and epidemiology:

Within natural environments, viruses evolve in response to host diversity. The most diverse communities tend to generate diverse viruses. A virus emerging from the environment into a human population, such as SARS-CoV-2 in 2019, may cause a serious epidemic among hosts whose immune systems have no prior exposure to the new pathogen. See IMPACT for a particularly compelling case of human viral pathogens emerging among African primate hosts.

A portrait of a small gray and orange monkey with protruding eyes sitting on a branch. The monkey is staring directly at the camera. Its body is covered in a layer of thick, fluffy hair. Tufts of hair line the edges of its angular ears.

impact

Monkey Business and Deadly Viruses

In 2014, an outbreak of Ebola virus devastated the countries of Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, and some cases reached countries outside Africa. Ebola virus, HIV, and mpox (formerly called monkeypox) virus—where did they come from? These very different viruses all came from apes and monkeys, our nearest relatives in Africa, the birthplace of humans and other primate species. As primates (including humans) evolved, our viruses evolved with us—and continue to do so. A virus needs to find new hosts. It may jump from one species to a closely related one. A region such as Africa, with rich diversity of our closest animal relatives, is also a rich source of emerging viral pathogens. For example, Ebola virus causes outbreaks in gorillas and chimpanzees, killing large numbers of animals. The dead animals are then found by hunters, who bring them home to feed their families. This consumption of “bushmeat” can then lead to a human outbreak of Ebola.

Nathan Wolfe is a professor at Stanford University who studies emerging viruses around the world (Figure IMPACT 12.1). Wolfe’s aim is to prevent future pandemics by predicting viral emergence before a pandemic occurs. For example, Wolfe’s team reported an outbreak of mpox among humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. He showed that the outbreak correlated with the decline in smallpox vaccination following the extinction of smallpox; the vaccination had previously cross-protected humans against mpox transmitted from monkeys. A slight mutation of mpox could lead to a global outbreak of smallpox-like disease. In fact, Wolfe argues, humanity has been extremely “lucky” with recent pandemics, such as AIDS: if HIV could spread as easily as smallpox, think how many more people would have died. In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, Wolfe proved prescient: a mutant and highly infectious coronavirus caused widespread mortality.

A photo of Professor Nathan Wolfe walking through a dense, forested area. He is focused on his work, looking out into the trees. Wolfe is wearing clothing that covers his arms and legs. He is carefully navigating his way over fallen trees and plant growth.

In his work, Wolfe travels among African villages, testing monkeys for new viruses. In one study, he found monkeys harboring new kinds of human T-lymphotrophic viruses (HTLVs), retroviruses related to HIV. He reported two strains, HTLV-3 and HTLV-4, never before seen, their effects on humans unknown. Many more such strains must exist in the wild. To avoid introducing such strains into humans, Wolfe urges the local hunters to avoid eating monkeys, especially dead monkeys they find in the forest—monkeys that may have died of viral disease. But the local people need these dead monkeys to feed their families; the alternative may be starvation.

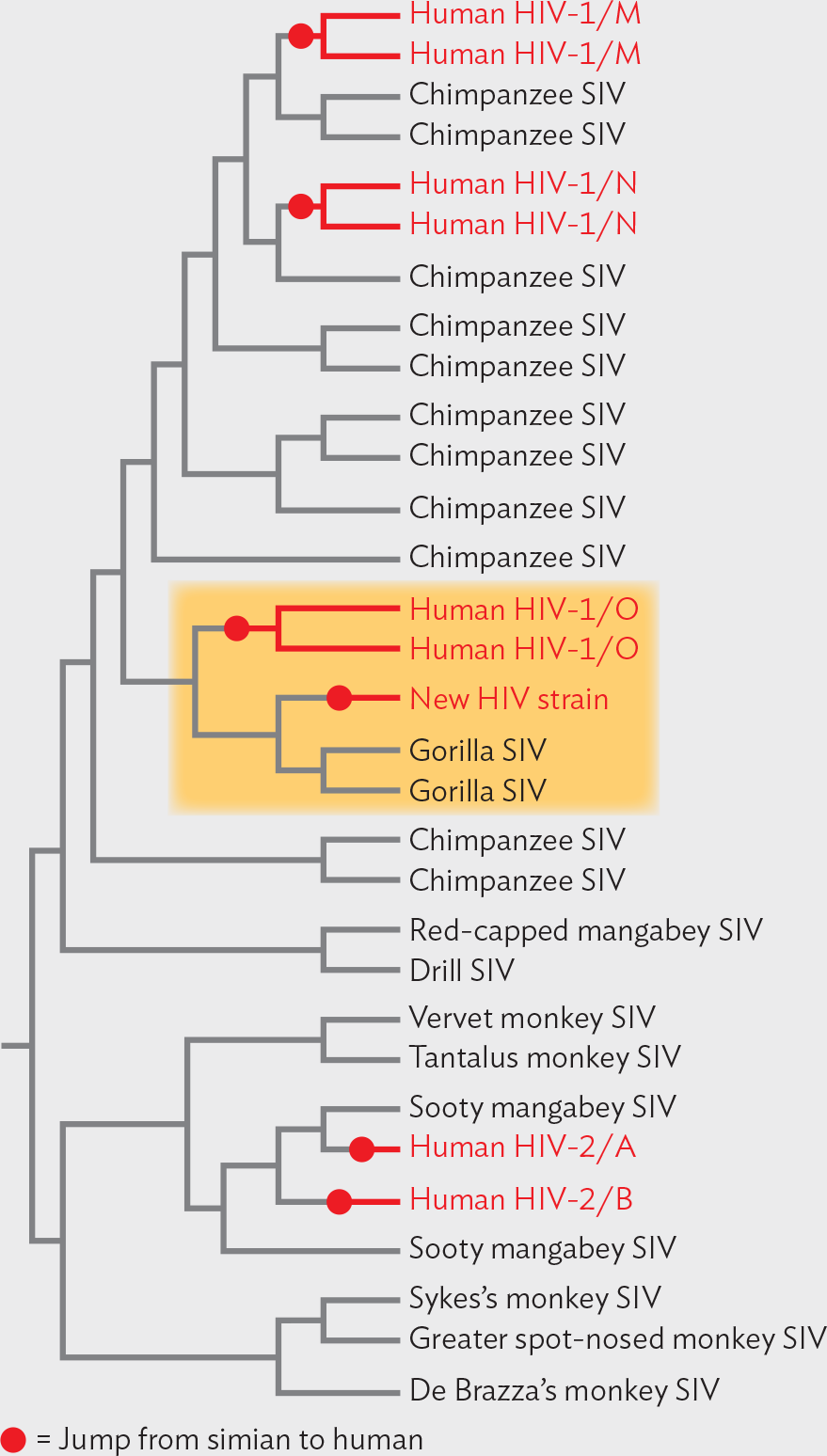

Although the circumstantial evidence is compelling, can we actually prove the host source of a given virus? At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, professor Beatrice Hahn used laboratory methods to do just that, tracing the precise origin of HIV. The cause of AIDS, HIV has one of the highest mutation rates of any virus, and it evolves quickly. Hahn performed statistical comparisons of various HIV strains with strains of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV), viruses closely related to HIV that cause immunodeficiency in monkeys. She sequenced the genomes of 50 new SIV strains from chimpanzees in southern Cameroon. Some of the SIV strains she found were even more closely related to HIV than any SIV strain found before. Her work established the statistical likelihood that the major HIV strain affecting North America and Europe (group M) diverged specifically from SIV strains in chimpanzees of Cameroon (Figure IMPACT 12.2).

A diagram of Beatrice Hahn’s phylogenetic tree of H I V strains. Nine of the end strains are marked as a jump from simian to human. The tree starts at the root, and it divides into two major groups. The first group is divided into two clusters. The first cluster has three strains. The second cluster has six strains. The two that are marked as a jump are human H I V 2 A and 2 B. This jump was from Sooty mangabey S I V to human. The second major group branches to form five clusters. The first cluster shows four strains. The second cluster has five strains. This cluster is highlighted. There is a new H I V strain and two Human H I V 1 slash O strains that are marked as a jump. This jump was from gorilla S I V to human. The third cluster has six strains for chimpanzee S I V. The fourth cluster has three strains. There are two H I V 1 slash N strains that are marked as a jump. This jump was from chimpanzee S I V to human. The fifth cluster has four strains. There are two Human H I V 1 slash M strains that are marked as a jump. This jump was from chimpanzee S I V to human.

The emergence of HIV group M in humans occurred well before 1960. But in 2009, researchers reported a much more recent emergence of a novel HIV strain in a Cameroonian woman—a strain never before seen in humans. This strain showed closest relatedness to an SIV strain in gorillas. Thus, a new kind of HIV was “caught in the act” of emerging from our primate relatives.

Although primates are a source of deadly viruses, they also provide our key source of information on how to combat these pathogens. For instance, SIV infects certain primate species without causing any symptoms. A monkey called the sooty mangabey shows no symptoms, despite high SIV titers, whereas the rhesus macaque develops simian AIDS. By studying the host response of monkeys that resist the virus, we may derive clues suggesting therapies for human AIDS.

In regions where mpox is endemic, should smallpox vaccination be resumed?

Now that we have introduced the major principles of virology, we are ready to examine the culture and replication cycles of a bacteriophage and of four different human-infecting viruses: papillomavirus (dsDNA), SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus [(+) sense RNA], influenza virus [(−) sense RNA], and HIV (retrovirus).

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 12.2 Which viruses have a narrow host range, and which have a broad host range?

An example of a virus with a narrow host range is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HIV causes AIDS only in humans, not even in chimpanzees, our nearest genetic relative. Poliovirus infects humans and chimpanzees but not nonprimate animals. A virus with a potentially broad host range is influenza virus. Influenza strains can infect different species of animals, but most strains cause disease in only one type of animal (humans, pigs, or birds). On the other hand, rabies virus has a broad host range, infecting many kinds of mammals.

Thought Question 12.3 What are the advantages to the virus of having a small genome? What are the advantages of a large genome?

For a virus, the advantage of a small genome is that the smaller the genome, the greater the number of progeny virions that can be formed from the nucleotides available. The host cell contains a limited supply of nucleotides, which may determine the number of virions made. A smaller genome saves space in a small capsid, and smaller capsids require less energy and resources than larger ones. On the other hand, a large viral genome enables the virus to encode products with many extra functions that help control the host cell. For example, herpesviruses encode products that modulate the host immune system, preventing it from stopping the virus.