SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe the structure of the HIV virion.

- Explain the replication cycle of HIV.

- Explain how endogenous retroviruses contribute to the human genome.

- Describe how HIV-derived vectors are used for genetic therapy.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

CASE HISTORY 12.3

Lifelong Infection by a Retrovirus

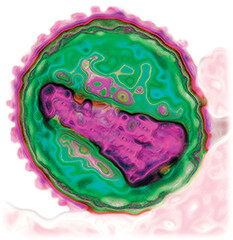

A transmission electron micrograph of an H I V virion. The virion is roughly spherical. The envelope forms a distinct border around the outside of the virion. The genome is located in the center of the virion. It forms an irregular somewhat rectangular shape.

Now Ralph faced the dilemma of how to avoid infecting his future wife and how to conceive healthy children. The doctor recommended antiretroviral therapy (ART) consisting of a single daily pill containing two medications such as tenofovir and emtricitabine (reverse transcriptase inhibitors). ART halts the decline of T cells and decreases the risk of transmission. For added security, Ralph’s girlfriend could choose to take preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) antiviral therapy as a preventive measure. The current view of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) is that “a person living with HIV who is on treatment and has an undetectable viral load cannot sexually transmit HIV.” Once Ralph got his viral load down, transmission would be unlikely.

Ralph and his girlfriend were also told of options for conceiving children without infection, such as the “sperm washing” procedure that eliminates HIV from sperm for artificial insemination. By following the doctor’s instructions and continuing therapy, Ralph could expect a healthy life with his family.

What is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and what is its global impact today? HIV is the causative agent of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and is a member of the lentivirus family (Baltimore Group VI; see Table 12.1). A lentivirus is a retrovirus that causes infections that progress slowly over many years. According to the WHO, approximately 39 million people globally are estimated to be living with HIV, and over 600,000 people die of AIDS annually. In the United States, the first cases of AIDS were reported in 1981; four decades later, more than a million Americans are infected with HIV, and more than half a million have died of AIDS. Worldwide, HIV infects 1 in every 140 adults between the ages of 15 and 49, equally among women and men.

The experience of Ralph in Case History 12.3 is typical of HIV infection. At some point, Ralph must have acquired HIV through high-risk behaviors such as sexual contact (genital or anal) or sharing of needles. The virus infects helper T lymphocytes (or T cells), which are white blood cells of the active immune system; they are needed to activate the B cells that generate antibodies (described in Chapter 16). The initial infection often goes unnoticed, as flu-like symptoms subside, or there may be no symptoms at all. The patient’s initial immune response leads to a rebound of T cells and a drop in virion numbers. But without treatment, the virus eventually defeats the immune system and destroys the T cells. With the immune system destroyed, the patient succumbs to opportunistic infections.

In countries that can afford antiviral medications, when people are diagnosed with HIV infection before symptoms, prompt treatment can now ward off symptoms and prevent transmission. HIV-positive individuals need to take a combination of antiviral agents for the rest of their lives. With this therapy, patients can avoid infecting others and expect to enjoy a full lifespan.

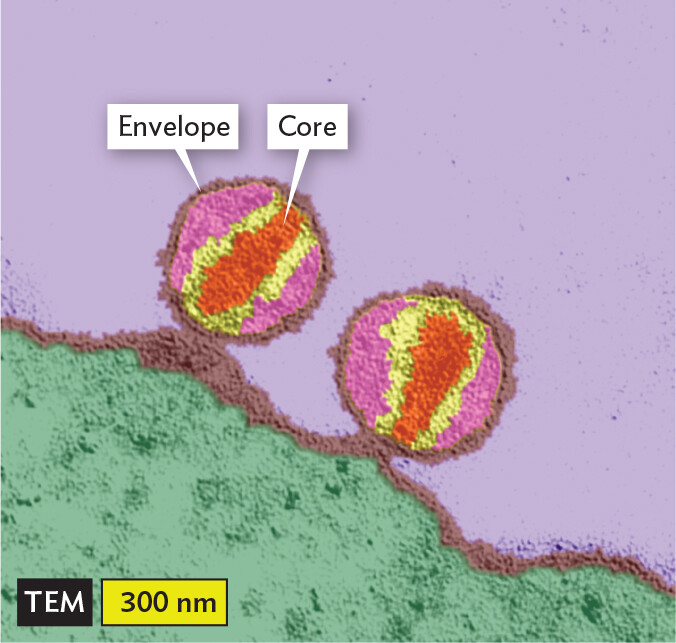

HIV and its causative role in AIDS were discovered by French virologists Luc Montagnier and Françoise Barré-Sinoussi, at the Pasteur Institute, building on Robert Gallo’s studies of retroviruses at the US National Institutes of Health (Figure 12.25). The virion has an unusual conical-icosahedral capsid (or core) enclosed in an envelope with spike proteins (Figure 12.26). After three decades of research, there is no cure for infection and no vaccine. But study of the HIV replication cycle has revealed a surprising array of effective therapeutic agents that enable a normal life and prevent transmission (Table 12.2). Therapeutic combinations of these drugs are called antiretroviral therapy (ART). ART effectively prevents AIDS for people infected with HIV, and it prolongs the life of people already exhibiting AIDS symptoms. Preventive treatment, called preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), can prevent infection and transmission. Unfortunately, the cost of antiviral drugs leaves treatment out of reach for the majority of those infected worldwide.

A photo of Francoise Barre Sinoussi. She is smiling at something beyond the view of the camera. She has short hair. Barre Sinoussi is wearing glasses and a light colored suit.

A photo of Luc Montagnier and Robert Gallo shaking hands. They are both wearing suits and smiling at each other.

A transmission electron micrograph of H I V 1 particles. The particles are spherical. They are in contact with the irregularly shaped membrane of a lymphoid tissue cell. Each particle has an envelope that forms a distinct outer border around the particle and a central core. The core is roughly ovoid in shape. Each particle has a diameter of about 300 nanometers.

|

Table 12.2 Antiretroviral Drugs Active against HIV |

|

|

Drug |

Mode of Action |

|

Azidothymidine (AZT), also called zidovudine (ZDV) |

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (base analog that halts elongation) |

|

Emtricitabine |

Cytidine analog, reverse transcriptase inhibitor |

|

Enfuvirtide |

Fusion inhibitor (prevents viral envelope fusion with host cell membrane) |

|

Maraviroc |

Entry inhibitor (binds host coreceptor CCR5 and thus blocks interaction with HIV spike protein) |

|

Nevirapine |

Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (binds reverse transcriptase and inhibits activity) |

|

Raltegravir |

Integrase strand transfer inhibitor (blocks integration of DNA genome copy into host cell genome) |

|

Ritonavir |

Protease inhibitor (inhibits the protease PR, which cleaves initial protein to make final proteins) |

|

Tenofovir |

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (base analog that halts elongation) |

The key polymerase of all retroviruses, including HIV, is reverse transcriptase. Reverse transcriptase is an enzyme that uses RNA as a template to synthesize DNA and then uses the new DNA as a template for the complementary DNA strand. Reverse transcriptase has the highest error rate of any known polymerase, possibly as high as one base in ten. For this reason, fewer than 1 in 1,000 progeny virions released in the blood are infectious. But the prodigious output of virions may reach 10 billion daily. So a large number will be infectious, and many of these will have mutations that evade the immune system and antiretroviral drugs.

To delay the loss of effectiveness due to viral mutation, HIV drugs are always taken in combinations of two or three, such as the ART combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine recommended for Ralph. Consequently, a mutant virion would need to have two or three lucky mutations to survive the drugs. But resistance inevitably occurs, and as people live for longer periods with HIV, new drugs are needed to replace the old ones.

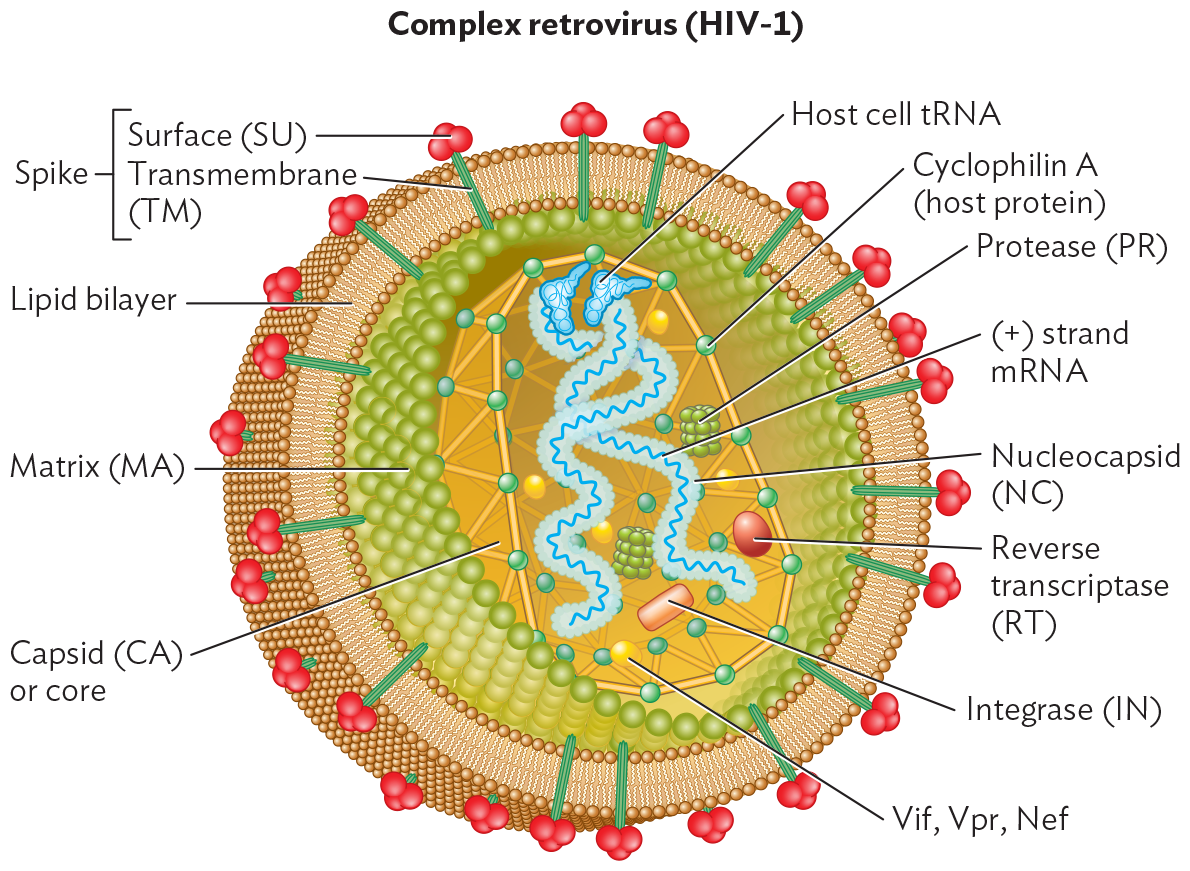

The structure of the HIV virion is depicted in Figure 12.27A. The conical core of capsid subunits encloses two copies of the RNA genome, together with reverse transcriptase and other enzymes. The presence of two genome copies is a unique feature of retroviruses. It may allow each genome to complement a defective mutation in the other genome, thus providing an essential function that might be missed.

An illustration of the structure of the H I V 1 virion, a complex retrovirus. The virion is spherical. It is enclosed within a lipid bilayer envelope. Embedded within the bilayer are spike proteins. These have two parts, a surface protein and a transmembrane protein. The surface protein has a bulbous rounded shape. The transmembrane protein is a rod shape that passes straight through the bilayer. The inner portion of the envelope is lined by matrix proteins. These form a sheet of tightly packed and highly organized spherical proteins. Inside of the matrix is the capsid, or core. The capsid consists of connected cyclophilin A proteins, derived from the host. The positive sense m R N A strand genome is contained within the capsid. It is enclosed within a protein layer called the nucleocapsid. Host cell t R N A is associated with the genome. Additional proteins and enzymes within the capsid are proteases, reverse transcriptase, integrase, V i f, V p r, and N e f.

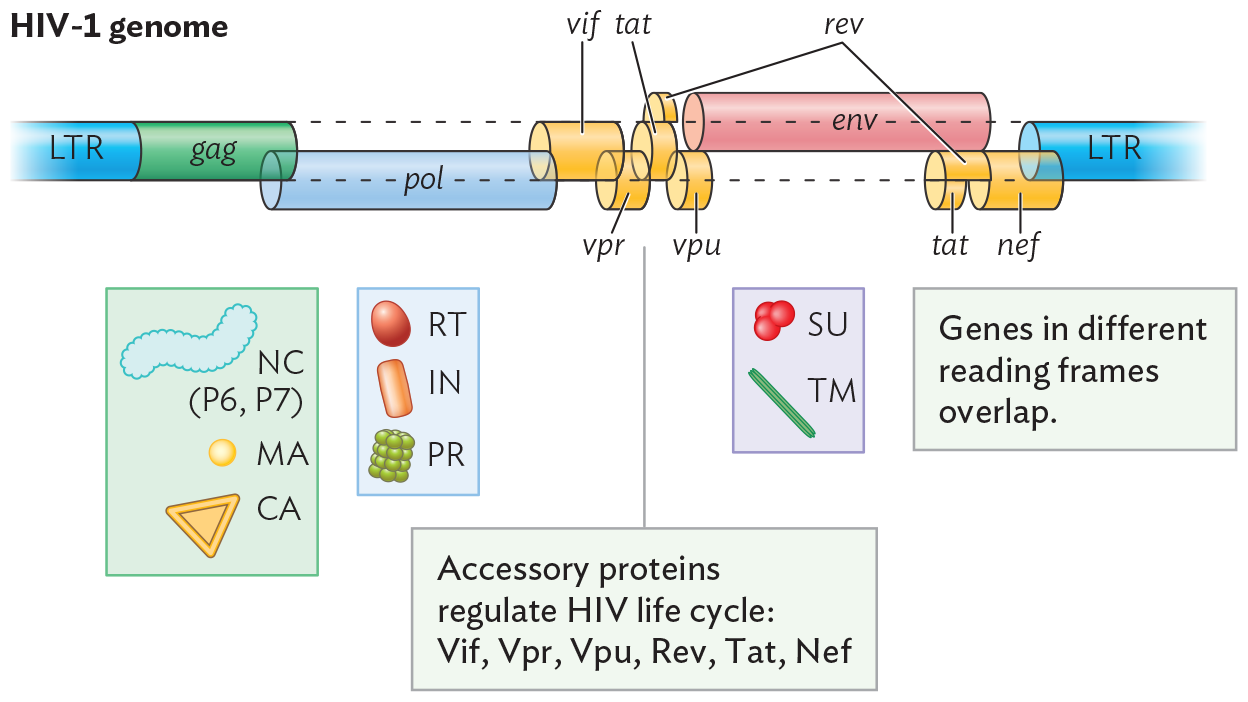

An illustration of the genome of H I V 1. The genome is shown as a horizontal tubular structure with twelve sections. The twelve sections display the genes G a g, P o l, V i f, V p r, T a t, V p u, R e v, E n v, and N e f. The genes are bordered by long terminal repeats on either end. These genes code for specific proteins used by the virus once it has entered the host cell. g a g codes for nucleocapsid components P 6 and P 7, matrix proteins, and capsid proteins. p o l codes for reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease. v i f, v p r, t a t, v p u, r e v, and n e f are accessory proteins that regulate the H I V life cycle. E n v codes for the surface and transmembrane components of the envelope spike proteins. It is noted that genes in different reading frames overlap.

Animation: HIV Replicative Cycle

Each RNA genome is coated with nucleocapsid proteins similar in function to those of influenza virus. For priming DNA synthesis (reverse transcription), each RNA is complexed with a tRNA derived from the previously infected host cell. The capsid also contains about 50 copies of reverse transcriptase (RT) and protease, as well as a DNA integration factor—all of which are potential drug targets (see Table 12.2). The core is surrounded by matrix proteins that reinforce the host-derived phospholipid viral envelope. The envelope is pegged by spike proteins composed of the subunits TM and SU. As in influenza virus, the spike proteins play crucial roles in host attachment and entry.

The HIV genome (Figure 12.27B) includes three main genes that are found in all retroviruses: gag, pol, and env. Each gene encodes a polyprotein (as we saw for coronavirus). The gag sequence encodes capsid, nucleocapsid, and matrix proteins; pol encodes reverse transcriptase (RT), integrase, and protease; and env encodes envelope proteins. The gag and pol sequences overlap, but (as in papillomavirus) they are translated in different reading frames. Each gene can express two or three different products, which arise by different start sites of transcription and by cleavage of a polyprotein. The retroviral genome evolves for extreme economy of RNA content, maximizing the information potential of its tiny genome.

The first cells infected by HIV are T lymphocytes (T cells) that possess cell-surface proteins called CD4 (the “receptor”) and CCR5 (the “coreceptor”). As we have seen for other virus-binding host proteins, these receptors have important functions for the host. CD4 helps the T cell activate the immune response (discussed in Chapter 16). CCR5 is a receptor for a chemokine, an immune system signal. The CD4 function is essential for the host, but CCR5 is dispensable. Thus, people who carry a genetic defect for CCR5 have a functional immune system but resist infection by HIV-1, the main strain of HIV causing AIDS. The drug maraviroc was designed to prevent HIV infection by blocking CCR5.

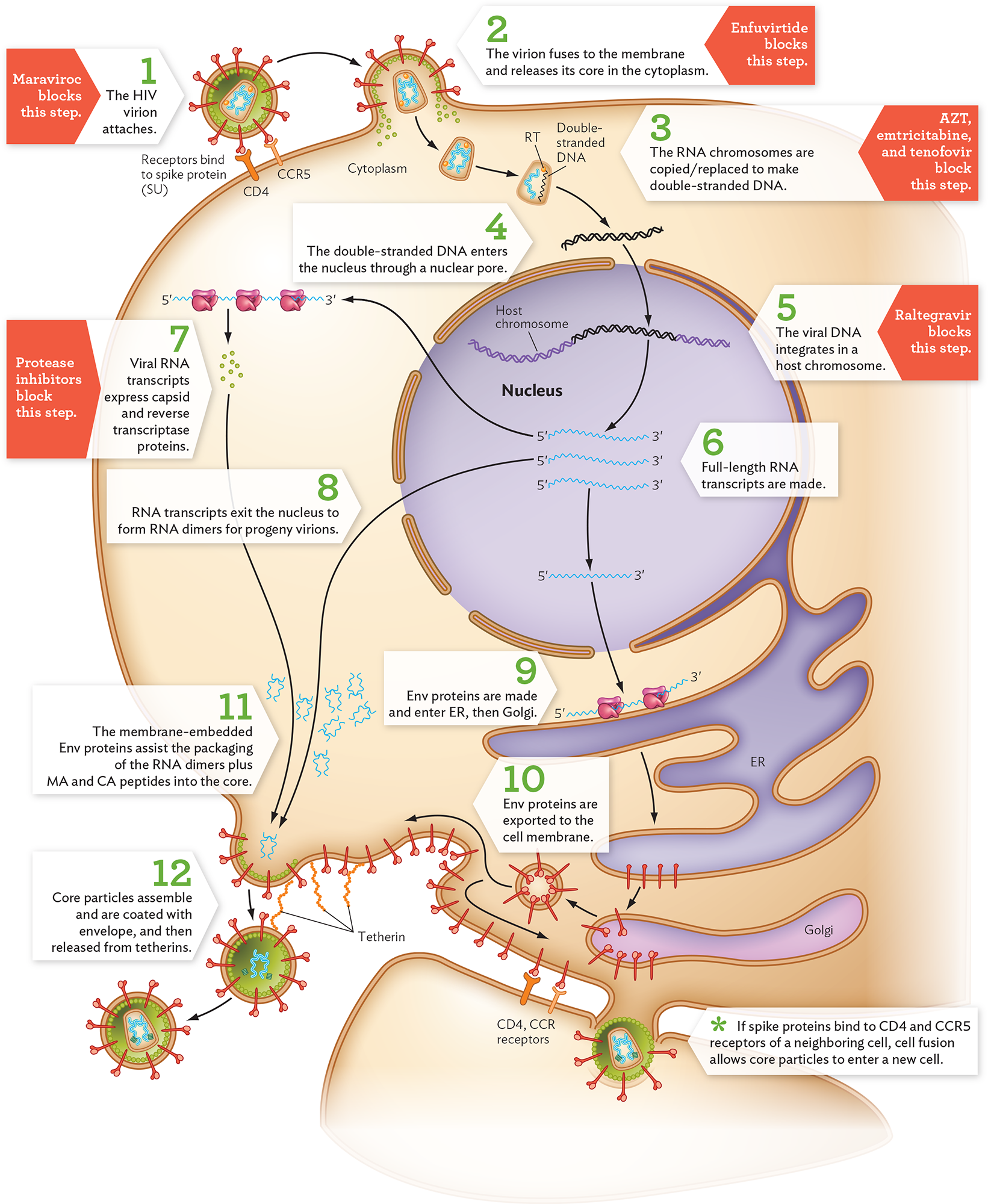

As an HIV virion binds the CD4 and CCR5 receptors (Figure 12.28, step 1), its envelope fuses with the cell membrane of the T cell (step 2). This fusion step can be blocked by drugs such as enfuvirtide. Unlike influenza virus, the HIV core is released directly into the cytoplasm, without endocytosis. In Steps 3 and 4, the core particle enters the nucleus through a nuclear pore (whether before or after DNA synthesis remains uncertain). The two RNA genome copies are reverse-transcribed by reverse transcriptase enzyme. Reverse transcription actually forms double-stranded DNA—a process that involves cleaving away the original RNA template and replacing it with DNA. Reverse transcription can be inhibited by azidothymidine (AZT) and emtricitabine, which are base analogs (molecules with structure similar to a nucleobase). These base analogs are chain terminators; they cannot attach the next nucleotide.

A diagram of the H I V replication cycle. There is a host cell shown with the nucleus, endoplasmic reticulum, and Golgi apparatus. The H I V virion is a spherical structure with spikes all over the external layer. There is a capsid at the center of the virion containing the genome. The cell membrane shows the Y-shaped receptors, C D 4 and C C R 5, which bind to the spike protein on the H I V virion. In step 1, the H I V virion attaches. Maraviroc blocks this step. In step 2, the virion fuses to the membrane and releases its core in the cytoplasm. Enfuvirtide blocks this step. In step 3, the core dissolves and the R N A chromosomes are copied or replaced to make double stranded D N A. A Z T, emtricitabine, and tenofovir block this step. The illustration shows double stranded D N A from the core entering the nucleus. In step 4, the double stranded D N A enters the nucleus through a nuclear pore. The viral D N A is now seen as part of a longer piece of D N A. In step 5, the viral D N A integrates into the host chromosome. Raltegravir blocks this step. In step 6, full length R N A transcripts are made. Three 5 prime to 3 prime m R N A transcripts are shown. All three leave the nucleus. One of the transcripts leads to three ribosomes that produce small spheres. In step 7, viral R N A transcripts express capsid and reverse transcriptase proteins. Protease inhibitors block this step. In step 8, another of the R N A transcripts exit the nucleus to form R N A dimers for progeny virions. The final m R N A transcript leads to ribosomes on the E R. The E R is a multi lobed structure. In step 9, e n v proteins are made and enter the E R and then the Golgi. Rod like structures are formed and are packaged in a vesicle. In step 10, E n v proteins are exported to the cell membrane. The rod like structures are now on the host cell membrane including where the produced viral proteins and R N A dimers are congregated. A bulge is forming in the membrane around the R N A dimer. In step 11, the membrane embedded E n v proteins assist the packaging of the R N A dimers plus matrix and capsid peptides into the core. The bulge forms a circle and separates from the cell. In step 12, core particles assemble and are coated with the envelope and then released from tetherins. Another bulge is shown entering a neighboring cell. A note reads that if spike proteins bind to C D 4 and C C R 5 receptors of a neighboring cell, cell fusion allows core particles to enter a new cell.

The double-stranded DNA copy of the HIV genome integrates as a provirus (or episome) at a random position in a host chromosome (step 5). Integration is a critical step; it ensures permanent infection of the host. The integrase enzyme can be blocked by inhibitors such as raltegravir. The entire length of the integrated HIV genome is transcribed to RNA by the host RNA polymerase II (step 6). Some of the RNA copies exit the nucleus to serve as mRNA for translation to proteins (step 7). Polyproteins are synthesized in alternative versions, such as Gag-Pol. The formation of alternative versions involves cleavage by a viral protease. Late in replication, the viral protease breaks up the Gag and Pol polyproteins into smaller, active proteins such as MA and CA. Viral protease can be blocked by protease inhibitors, another major category of antiviral drugs (see Table 12.2).

Some full-length RNA transcripts exit the nucleus to be packaged as genomes for progeny virions (Figure 12.28, step 8). Meanwhile, Env (envelope) proteins are made within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER; step 9). They pass through the Golgi for glycosylation (adding sugar chains) and packaging and are exported to the cell membrane (step 10). At the membrane, Env proteins interact with the core particle as it forms from the RNA dimers plus Gag-Pol peptides (step 11). During particle assembly, Gag-Pol peptides are cleaved by protease to form the capsid protein CA and the matrix protein MA. (This protease step is a target of protease inhibitors, a major class of anti-HIV drugs.) The CA and MA subunits form a mature core particle enclosing the HIV genome, with reverse transcriptase and integrase proteins ready for the next infection. The mature virions then bud out of the host cell—a process that requires cleavage of a host attachment protein called tetherin (step 12).

An alternative to viral budding is cell fusion, mediated by the binding of Env in the membrane to CD4 receptors on a neighboring cell. Cell fusion occurs because, unlike influenza virus, which rapidly destroys the host cell, HIV can persist in a host cell for long periods. The HIV-infected cell buds out virions while continuing to display Env proteins on the plasma membrane. Thus, an infected cell can fuse with an uninfected cell, and HIV core particles can enter the new cell through their fused cytoplasm. The fusion of many cells can form a giant multinucleated cell called a syncytium (plural, syncytia). Cell fusion enables HIV to infect neighboring cells without exposure to the immune system.

Suppose an integrated HIV genome mutated and lost the ability to produce progeny. What would happen to its genome? The integrated genome would be “trapped,” replicating only as part of the host genome. Over many generations in its host, the viral sequence would inevitably accumulate more mutations. In fact, the human genome is riddled with remains of decaying retroviral genomes, collectively known as retroelements. Some retroelements contain all the genomic elements of a retrovirus, including gag, env, and pol genes, yet never generate virions. Presumably, the integrated retroviral genome lost this ability by mutation. Other elements, known as retrotransposons, retain only partial retroviral elements but may maintain a reverse transcriptase to copy themselves into other genome locations. Amazingly, about half the sequence of the human genome appears to have originated from viruses and retroelements.

Could a virus as deadly as HIV be used to improve human health? In fact, the exceptional ability of lentiviruses to deliver their genomes into a human genome makes them the most promising source of vectors for gene therapy. To be used for gene therapy, the integration sequences are maintained while the virulence genes are removed and replaced by human genes to be delivered by the lentiviral vector (or lentivector). In 2009, a lentiviral vector was used to successfully treat two children with an inherited neurodegenerative disease, X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD). The vector transferred a corrected version of the gene into the children’s bone marrow stem cells, which then migrated into the brain and halted disease progression.

Lentivectors have been devised to modify T cells to treat certain forms of leukemia. In 2013, a child named Emily Whitehead was cured of leukemia using an HIV-derived vector to carry genes into her T cells, a procedure called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapy. The transferred genes caused her T cells to fight the cancer. CAR-T therapy has since been approved by the FDA to treat several forms of B-cell leukemia and multiple myeloma. Looking to the future, we can expect many health-transforming applications from these deadly viruses.

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 12.7 How do attachment and entry of HIV resemble attachment and entry of influenza virus? How do attachment and entry differ between these two viruses?

Both HIV and influenza viruses attach to their host cell by their envelope spike proteins binding to host receptors. For HIV-1, the Env protein binds receptors CD4 and CCR5; for influenza, the HA envelope protein binds to host glycoproteins. However, the two viruses enter their host cells by different routes. Influenza virus induces formation of an endocytic vesicle, whose acidification triggers membrane fusion and release of the core contents into the host cytoplasm. HIV virions, however, do not induce endocytosis and do not require acidification. The HIV envelope fuses with the cell membrane to release the core particle into the cytoplasm. In addition, HIV virions can travel between cells via fusion of an infected cell with an uninfected cell.