SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Describe the various portals of entry and exit for microbial pathogens.

- Discuss concepts of biosafety and biocontainment.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

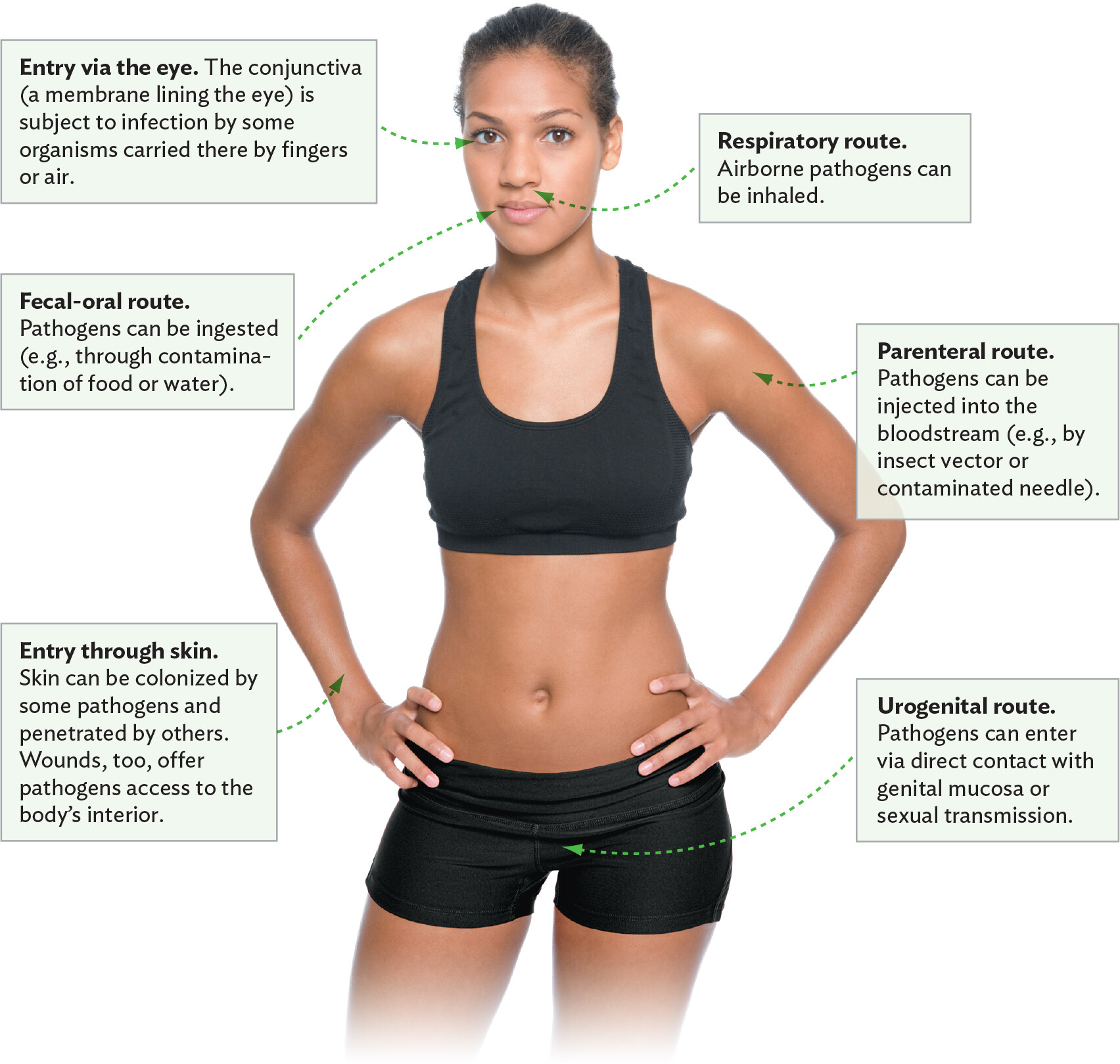

How do infectious agents gain access to the body? Each organism is adapted to enter the body in different ways (Figure 2.14). Food-borne pathogens (for example, Salmonella, E. coli, Shigella, and rotavirus) are ingested by mouth and ultimately colonize the intestine. They have an oral portal of entry (fecal-oral route of infection). Airborne pathogens such as SARS-CoV-2 virus, Legionella pneumophila, and Aspergillus fumigatus, in contrast, infect through the respiratory tract (respiratory route). Some microbes enter through the conjunctiva of the eye; others enter through the mucosal surfaces of the genital and urinary tracts (urogenital route). Agents that are transmitted by mosquitoes or other insects enter their human hosts via the parenteral route, meaning injection into the bloodstream. Wounds and needle punctures can also serve as portals of entry for many microbes. Shared needle use between drug addicts has been a major factor in the spread of HIV and hepatitis C. Even syphilis can be transmitted by sharing used needles.

A diagram explaining the different portals of entry or modes of transmission of a pathogen. At the center of the diagram is a photo of a woman facing the viewer. One portal of entry is the eye. The conjunctiva, a membrane lining the eye, is subject to infection by some organisms carried there by fingers or air. Another portal of entry is through the skin. The skin can be colonized by some pathogens and penetrated by others. Wounds, too, offer pathogens access to the body’s interior. One mode of transmission is the fecal oral route. Pathogens can be ingested from contaminated food or water. Another mode of transmission is the respiratory route. Airborne pathogens can be inhaled. Another mode of transmission is the parenteral route. Pathogens can be injected into the bloodstream, such as by an insect vector or a contaminated needle. Another mode of transmission is the urogenital route. Pathogens can enter this route via direct contact with genital mucosa or sexual transmission.

Denying a pathogen access to its portal of entry is an effective way to halt the spread of disease. For example, condoms greatly limit the spread of sexually transmitted infections. When used properly, hospital-quality face masks (N95 or KN95) are effective at minimizing airborne transmission of influenza, SARS-CoV-2, and other respiratory tract pathogens (Figure 2.15A). The mask must have two straps that go around your head (not ear loops), fit your face snugly, and be worn consistently when in crowds. Wash your hands after removing the mask, and discard it after a week (or daily if in a hospital setting). Some have questioned the effectiveness of these masks during he COVID-19 pandemic. The problem was not the masks though, rather with incorrect and inconsistent mask use as well as infrequent hand washing following public outings. Cloth masks, however, such as those used during the deadly 1918 influenza pandemic were useless because they do not filter viruses (Figure 2.15B). Simple behaviors like covering a sneeze with the inside of your elbow and handwashing can also limit the spread of respiratory diseases.

A modern photo of a person donning a virus filtering mask. The mask has two straps that ensure a secure fit. One strap loops around the neck and the other strap loops around the crown of the head. A metal band allows for a tight fit to the bridge of the nose. The mask covers a large portion of the persons lower face, including their nose, mouth, chin, and cheeks.

A historical photo of policemen wearing gauze face masks during the influenza pandemic of 1918. The photo is in greyscale. The officers are wearing dark uniforms and police hats or helmets. The masks fit loosely over the officers nose, mouth, chin, and cheeks. Two straps, one around the neck and another around the back of the head, keep the masks on their faces. The masks are made of a material that is unable to filter viruses.

Why does a pathogen use one portal of entry and not another? One factor is the pathogen’s reservoir. Is the agent found in contaminated food (as for Salmonella bacteria), or can it be aerosolized by a sneeze (like influenza virus)? The first example favors ingestion; the second, inhalation. Is its natural reservoir an animal (as with Francisella, the subject of Case History 2.3 below)? If so, then organisms can be transmitted to hunters who cut themselves while cleaning a dead animal (the parenteral route) or by insect vectors that can feed on the animal and then on humans.

Portal-of-entry preference is also related to the pathogen’s attachment capability. Some pathogens have access to many different entry points but can establish infection through only one. Different body tissues have different receptor structures on their surface, and the bacterium or virus must have a compatible receptor in order to bind. If it can’t bind, the pathogen can be expelled by the host. HIV, for instance, is not transmitted through respiration or by ingestion because the virus must enter the bloodstream to infect susceptible T lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell (Chapter 16).

Once a pathogen gets in the body, why and how does it get out? Hosts have a limited life span. When the host dies, the pathogen can die with it, owing to the lack of food. Even in a live host, microbial growth can be limited by the space in which the pathogen can grow. So, to continue propagating, most pathogens need to leave and find new hosts. You will learn more about microbial growth in Section 6.2.

Do pathogens leave the same way they came in? Not always. Obvious examples are diarrhea-causing bacteria and viruses, which enter by ingestion but leave by defecation, where they can again be ingested when food, water, or hands become contaminated (this is the fecal-oral route of transmission). Some organisms gain entrance through one route but disseminate to other organs, through which they then exit. A good example is Yersinia pestis, the agent in Case History 2.2. The bacterium enters the body by the parenteral route (via a flea bite) but spreads to the lung and is expelled by coughing (the respiratory route). On the other hand, some microbes do use the same portal to enter and exit the body. Influenza virus both comes and goes via the respiratory tract. Other microbes can enter and exit through multiple portals. For instance, HIV can enter and leave the body by the urogenital route or parenterally through injection and shared needles.

Note: In Chapters 19–24, which describe infectious diseases in greater detail, you will learn more about the portals of entry and exit for specific pathogens. Each of those chapters concludes with a summary figure that diagrams the portals of entry and exit of the key pathogens discussed in the chapter.

Note: In Chapters 19–24, which describe infectious diseases in greater detail, you will learn more about the portals of entry and exit for specific pathogens. Each of those chapters concludes with a summary figure that diagrams the portals of entry and exit of the key pathogens discussed in the chapter.

CASE HISTORY 2.3

Risky Business in the Lab

An illustration of a biohazard icon. The icon consists of a yellow triangle with a black symmetrical three part design at the center. The design includes three incomplete circles which do not overlap but connect at the center of the triangle.

Medical and laboratory personnel are exposed to extremely dangerous pathogens on a daily basis. The microbiologists in this case history did not protect themselves properly because they thought they were working with a nonvirulent strain of F. tularensis. As a result, they ended up with a laboratory-acquired infection. The CDC has published a series of regulations designed to protect laboratory workers and medical personnel who are at risk of infection by human pathogens. These are called “Universal Precautions” and “Standard Precautions,” respectively. Universal Precautions are based on the idea that all blood and body fluids should be treated as infectious because patients with blood-borne infections can be asymptomatic. Standard Precautions are similar but apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status. The eight Standard Precautions are as follows:

A photo of a clinician wearing personal protective equipment while attending to a patient. The patient extends their left arm to the clinician, who examines for signs of a flesh eating disease. The clinician is gowned in a disposable mask, gown, and gloves. The patient’s arm is red and irritated. A few darker, possibly ulcerated, spots are seen on their arm.

We will discuss sterilization and disinfection techniques more fully in Chapter 13.

In the laboratory, it is important to prevent the transmission of an infectious agent to laboratory personnel and the accidental release of agents into the environment. Infectious agents are ranked by the severity of disease and ease of transmission. On the basis of this ranking, four levels of agent containment are employed, as indicated in Table 2.4. (An expanded version of this table, including selected representative organisms at each level, is available in eAppendix 4, Table A4.1.)

|

Table 2.4 Biological Safety Levels (BSLs) and Select Agentsa |

||||

|

Biosafety Level |

||||

|

BSL-1 |

BSL-2 |

BSL-3 |

BSL-4 |

|

|

Class of Disease Agent |

Agents not known to cause disease. |

Agents of moderate potential hazard; also required if personnel may have contact with human blood or tissues. |

Agents may cause disease by inhalation route. |

Dangerous and exotic pathogens with high risk of aerosol transmission; only 13 labs in the United States handle these. |

|

Recommended Safety Measures |

Basic sterile technique; no mouth pipetting. |

Level 1 procedures plus limited access to lab; biohazard safety cabinets used; hepatitis vaccination recommended. |

Level 2 procedures plus ventilation providing directional airflow into room, exhaust air directed outdoors; restricted access to lab (no unauthorized people); respiratory protection and wraparound gowns. |

Level 3 procedures plus one-piece positive-pressure suits; lab is completely isolated from other areas present in the same building or is in a separate building. |

Biosafety level 1 organisms, such as E. coli K-12, have little to no pathogenic potential and require the lowest level of containment. Standard sterile techniques and laboratory practices are sufficient.

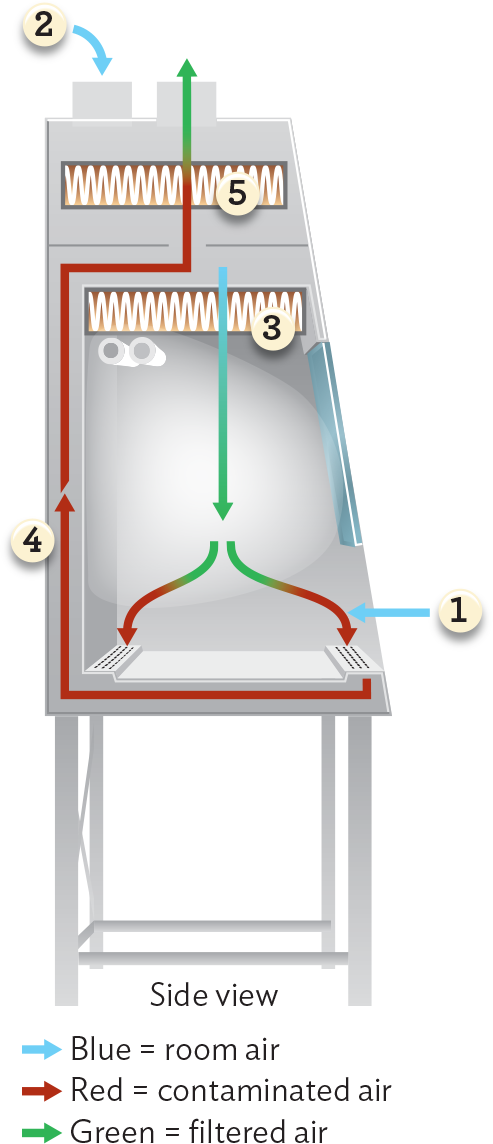

Biosafety level 2 agents, such as diarrheagenic E. coli, have greater pathogenic potential than level 1 agents but are readily treatable by vaccines and/or therapeutic treatments (for example, antibiotics). Biosafety level 2 agents require somewhat rigorous containment procedures, such as limiting laboratory access when experiments are in progress and using biological laminar flow cabinets if aerosolization is possible (Figure 2.17).

A photo of a scientist working in a biological safety cabinet. The scientist is wearing a lab coat, goggles, and gloves. A small gap between the glass sash allows her arms to reach under the hood where she examines a sample. Pipettes, beakers, and other laboratory supplies can be seen within the hood.

A diagram of airflow through a biological safety cabinet. Room air, represented with blue arrows, enters the cabinet through the gap in the glass sash or is pumped in through an H E P A filter at the top of the unit. Room air pumped in from the top is filtered by the first H E P A filter and released into the workspace as filtered air, shown as a green arrow. Upon either source of room air entering the working space of the cabinet, the air becomes contaminated, represented by red arrows. These red arrows are sucked down under the workspace, up the back of the unit, and through a second H E P A filter. This second H E P A filter releases filtered air, shown as green arrows, back into the environment.

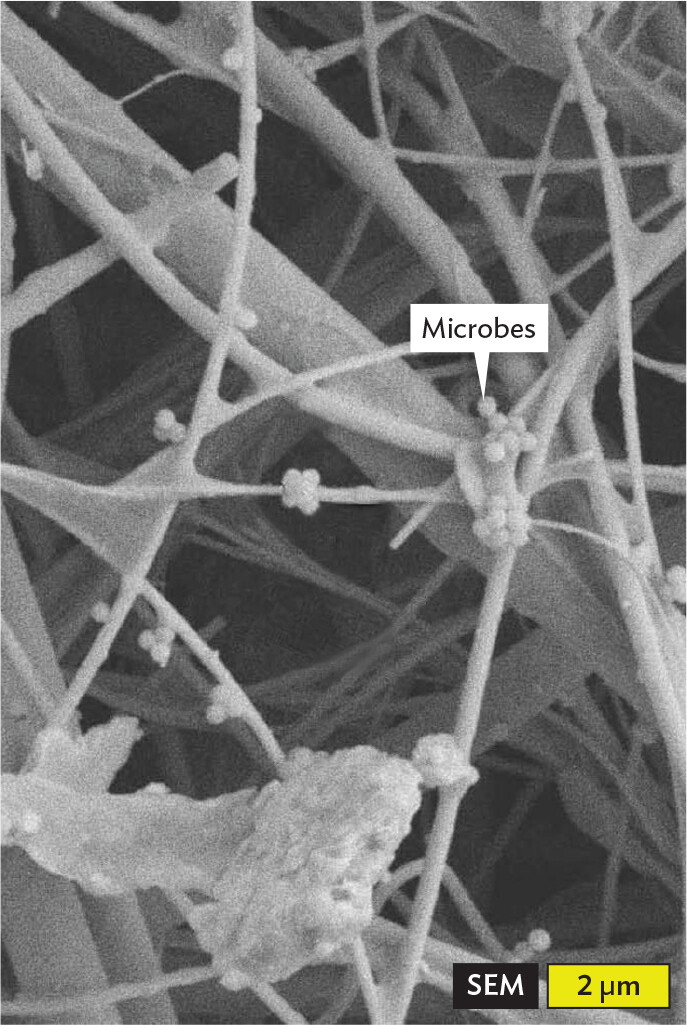

A scanning electron micrograph of microbes trapped in an H E P A filter. The filter is comprised of overlapping strands, which have the appearance of spindles or wires. Numerous spherical microbes are trapped along these strands. Each microbe has a diameter of about 0.25 micrometer.

Biosafety level 3 pathogens produce a serious or lethal human disease, but vaccines or therapeutic agents may be available. For safe handling of these organisms, level 2 procedures are supplemented with a lab design that ensures ventilation air only flows into the room (negative pressure) and that exhaust air passes through high efficiency filters (HEPA) before being vented directly to the outside. Negative pressure will keep any organism that may aerosolize from escaping into hallways. In addition, access to the lab is strictly regulated and includes double-door air locks at the entrance. This was the containment level needed to prevent accidental infection by F. tularensis in Case History 2.3 and is the containment level used for SARS-CoV-2 research.

By law, extremely dangerous pathogens such as the Ebola virus, as well as those for which no treatment or vaccine is available, are biosafety level 4 pathogens and may be studied only at a biosafety level 4 containment facility. Practices here dictate that lab personnel wear positive-pressure lab suits connected to a separate air supply (Figure 2.18). The positive pressure ensures that if the suit is penetrated, organisms will be blown away from the breach and not sucked into the suit. As of this writing, 13 biosafety level 4 laboratories are operating in the United States.

A photo of a doctor working in a positive pressure suit. The suit covers the doctor’s entire body. Most of the suit is made of a shiny, opaque material, but around the face is a transparent material through which the doctor can see. Coiled red tubing is attached to the suit. The doctor is wearing earplugs. The doctor holds out a set of samples on the bench before him.

Although these regulations may seem reasonable or even obvious, they were not always in effect. Before 1970, some scientists had an almost cavalier approach toward handling pathogens. For instance, culture material was routinely transferred from one vessel to another by mouth pipetting (essentially using a glass or plastic pipette as a straw). This practice is now forbidden for obvious reasons and has been replaced with mechanical pipettors that have disposable tips.

SECTION SUMMARY