SECTION OBJECTIVES

- Explain how light interacts with an object.

- Describe how refraction enables magnification, and explain the limits to magnification and resolution.

SECTION OBJECTIVES

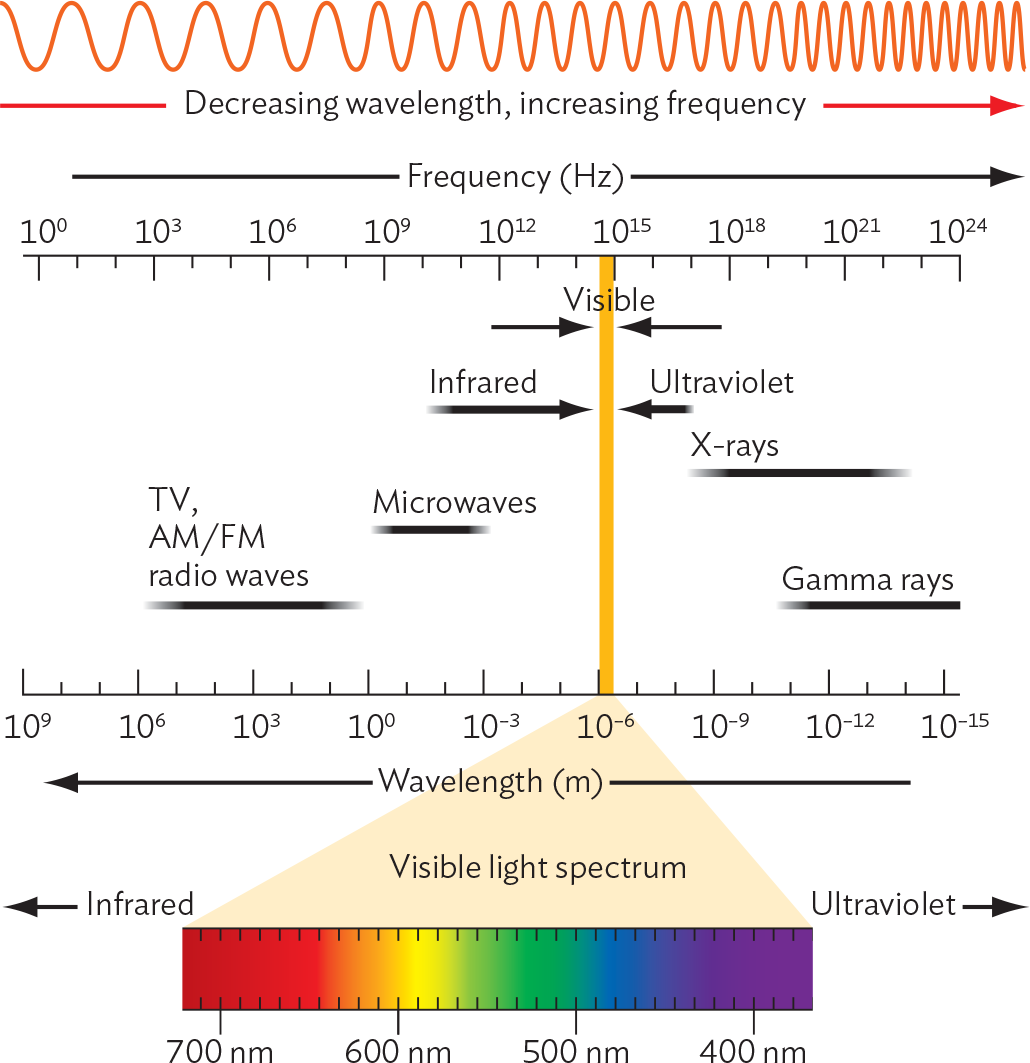

When you use a microscope, how does it make a tiny object appear large? Light microscopy extends the lens system of your own eyes. Light is a form of energy that is propagated as waves of electromagnetic radiation (Figure 3.8). The spectrum of light waves is defined by their wavelength, the distance between one peak of a wave and the next peak. The wavelength of visible light is about 400–750 nm, about 100 times less than the width of a human hair. Radiation of longer wavelengths includes infrared and radio waves, whereas shorter wavelengths include ultraviolet rays and X-rays.

An illustration of the different ranges of frequencies of electromagnetic radiation. At the top there is a wavy line. The peaks and troughs are more spread out on the left and closer together on the right. The amplitude of the waves remains the same. An arrow pointing left to right is labeled decreasing wavelength and increasing frequency. Below this is a chart showing the frequencies and wavelengths of different kinds of energy waves. The top line represents the frequency in hertz from 10 superscript zero to 10 superscript 24. The bar at the bottom represents wavelength in meters from 10 superscript 9 to 10 superscript negative 15. The visible spectrum, between seven hundred to four hundred nanometers, lies at a frequency of 10 superscript 15 Hertz and a wavelength of 10 superscript negative 6 meters. Below 400 nanometers are ultraviolet rays like x-rays and gamma rays. Above 700 nanometers are infrared rays like microwaves and T V or A M F M radio waves. An inset breaks down the visible light spectrum. The spectrum is red at 700 nanometers, transitions to orange, then yellow at 600 nanometers, to green at 500 nanometers, to blue between, and purple at 400 nanometers.

All forms of radiating energy that interact with an object carry information about the object. The information carried by radiation can be used to detect objects; for example, radar uses radio waves to detect a speeding car. For energy radiation to resolve an object (distinguish it) from neighboring objects or from its surrounding medium, certain conditions must exist:

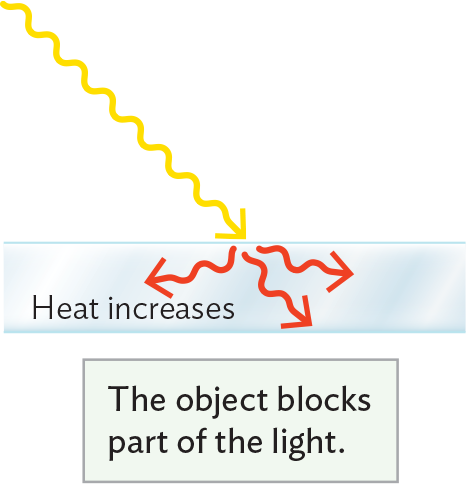

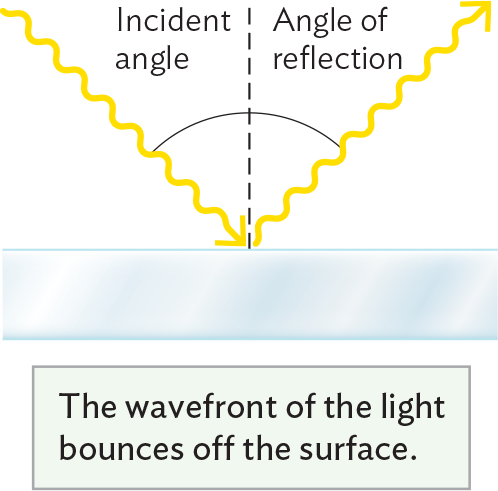

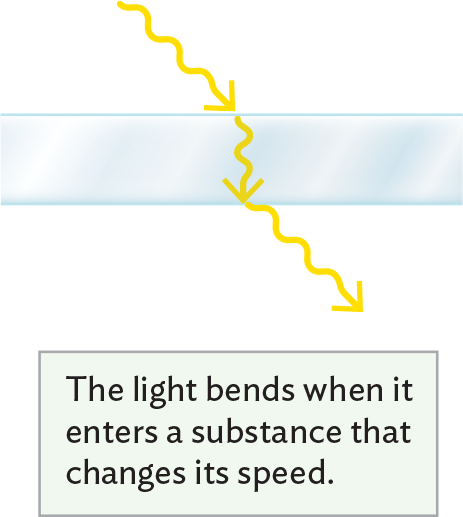

How does light interact with an object? The physical behavior of light in some ways resembles a beam of particles and in other ways resembles a waveform. The particles of light are called photons. Each photon has an associated wavelength that determines how the photon will interact with a given object. The combined properties of particle and wave enable light to interact with an object in several different ways: absorption, reflection, refraction, and scattering.

An illustration of the absorption of light. From the left, one light wave, represented by a wavy yellow arrow, travels angularly in a right and downward direction and hits a rectangular object at an angle. Energy from the ray scatters within the object as heat. It’s represented by three red wavy arrows pointing from the area the light ray hit the object out into three different directions. A caption reads, The object blocks part of the light.

An illustration shows the reflection of light. From the left, one light wave, represented by a wavy yellow arrow, travels angularly in a right and downward direction and hits a rectangular object at an angle. From where it hits the rectangular surface, another wavy yellow arrow emerges traveling at a reverse mirror angle to the first ray’s trajectory path. There is a center dotted vertical line drawn straight up from the rectangular surface. The angle between the first arrow and the dotted line is the incident angle. The angle between the second arrow and the dotted line is the angle of reflection. A caption reads, the wavefront of the light bounces off the surface.

An illustration shows the refraction of light. From the left, one light wave, represented by a wavy yellow arrow, travels angularly in a right and downward direction until it hits a rectangular object on the surface at an angle. Another arrow emerges from the point where the first arrow hit the rectangular surface. It travels straight down through the rectangle. At the edge of the other side of the rectangular object, this arrow stops. Another arrow begins here and travels angularly in a right and downward direction at the same angle as the initial ray of light. A caption reads, the light bends when it enters a substance that changes its speed.

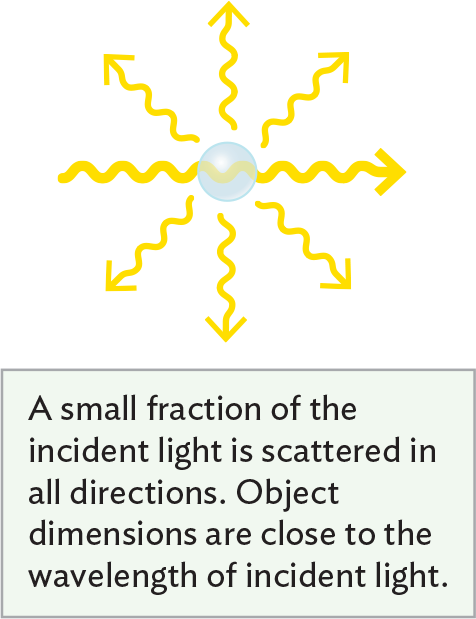

An illustration of the scattering of light. A bolded light ray travels directly through a translucent sphere. Six other non bolded rays begin from different areas on the surface of the object and extend outward in a radial pattern around the sphere. A caption reads, A small fraction of the incident light is scattered in all directions. Object dimensions are close to the wavelength of incident light.

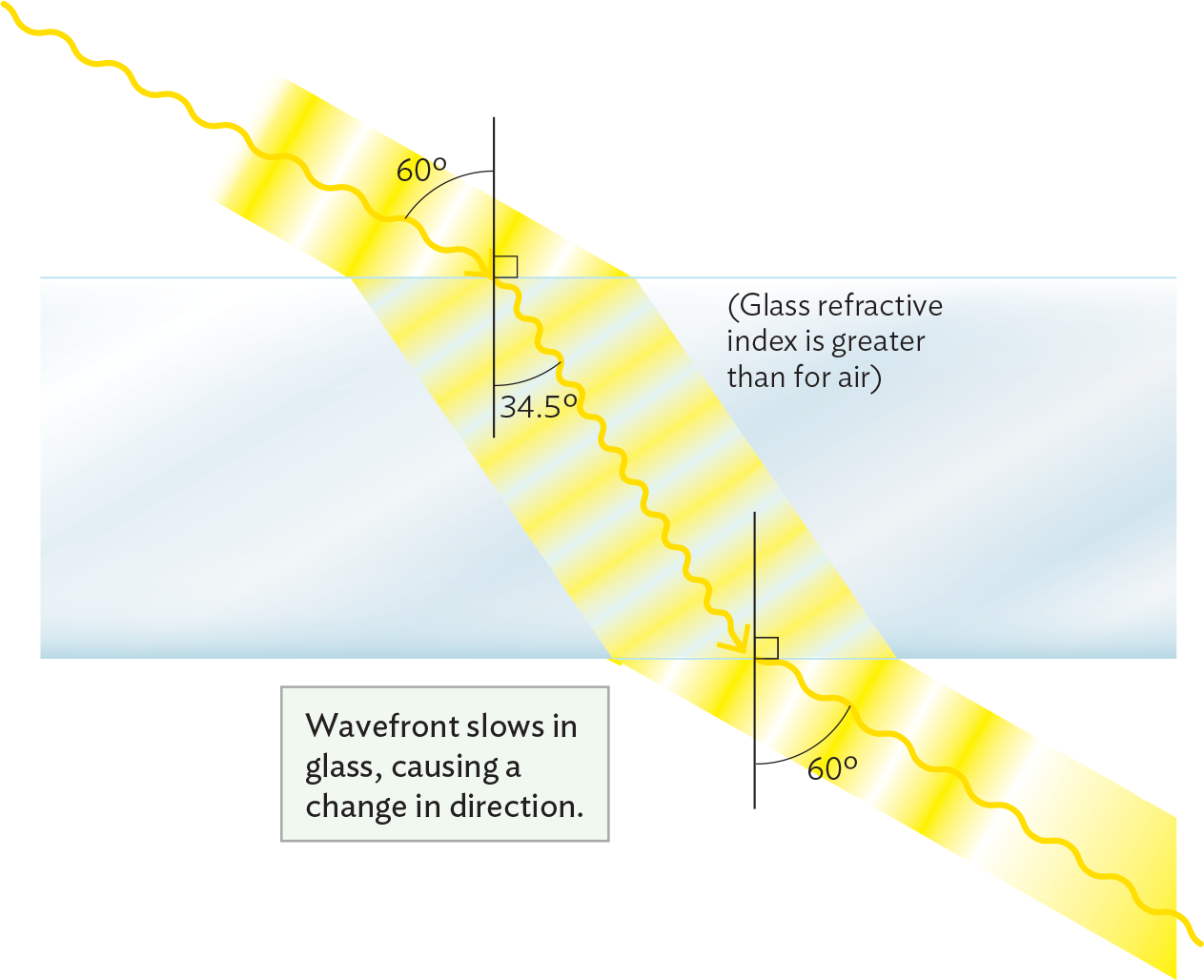

Magnification requires refraction of light through a medium of high refractive index, such as glass. As a wavefront of light enters a material of higher refractive index (slower speed of light), the region of the wave that first reaches the material is slowed, like the wheel of a car that enters a bank at the side of the road. Meanwhile, the rest of the wave continues at its original speed; thus, the wavefront bends until it passes into the refractive material (Figure 3.10). As the entire wavefront continues through the refractive material, its path remains at an angle from its original direction. As the wave reaches the opposite face of the refractive material, the wavefront bends in the opposite direction and resumes its original speed.

A diagram explaining the refraction of light waves through glass. A ray of light, expanded to form a wavefront, reaches the glass at an angle of 60 degrees. The speed of the wavefront slows as it passes through the glass, causing the angle of its trajectory to change to 34.5 degrees. When the wavefront exits the glass, it resumes its original speed and 60 degree trajectory angle. It is noted that the glass refractive index is greater than for air. A caption reads, Wavefront slows in glass, causing a change in direction.

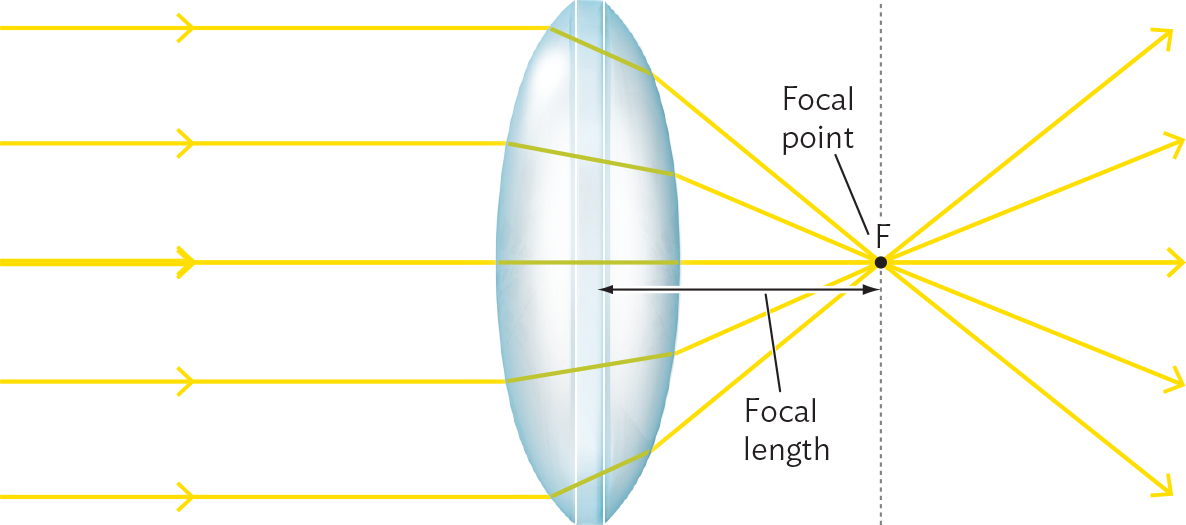

A refractive material with a curved surface can serve as a lens to focus light. Light rays entering a lens are bent at an angle such that all rays meet at a common point. Parallel light rays entering the lens emerge at angles, intersecting each other at the focal point (Figure 3.11). From the focal point, the light rays continue onward in an expanding wavefront. This expansion magnifies the image carried by the wave. The distance from the lens to the focal point (called the focal length) is determined by the degree of parabolic curvature of the lens and by the refractive index of its material.

An illustration of light rays passing through a lens to converge at a focal point. The lens is a curved, nearly ovoid, piece of glass. A series of parallel light rays enter the glass horizontally. The angle of the light rays changes upon entry into the lens. Rays closer to the narrower ends of the lens change to sharper angles. Rays near the broader center of the lens remain at a constant trajectory or angle only slightly. The rays converge at the same location, labeled the focal point, a short distance from the lens. After the focal point, the rays disperse, traveling in varied trajectories. The distance between the focal point and the center of the lens is referred to as the focal length.

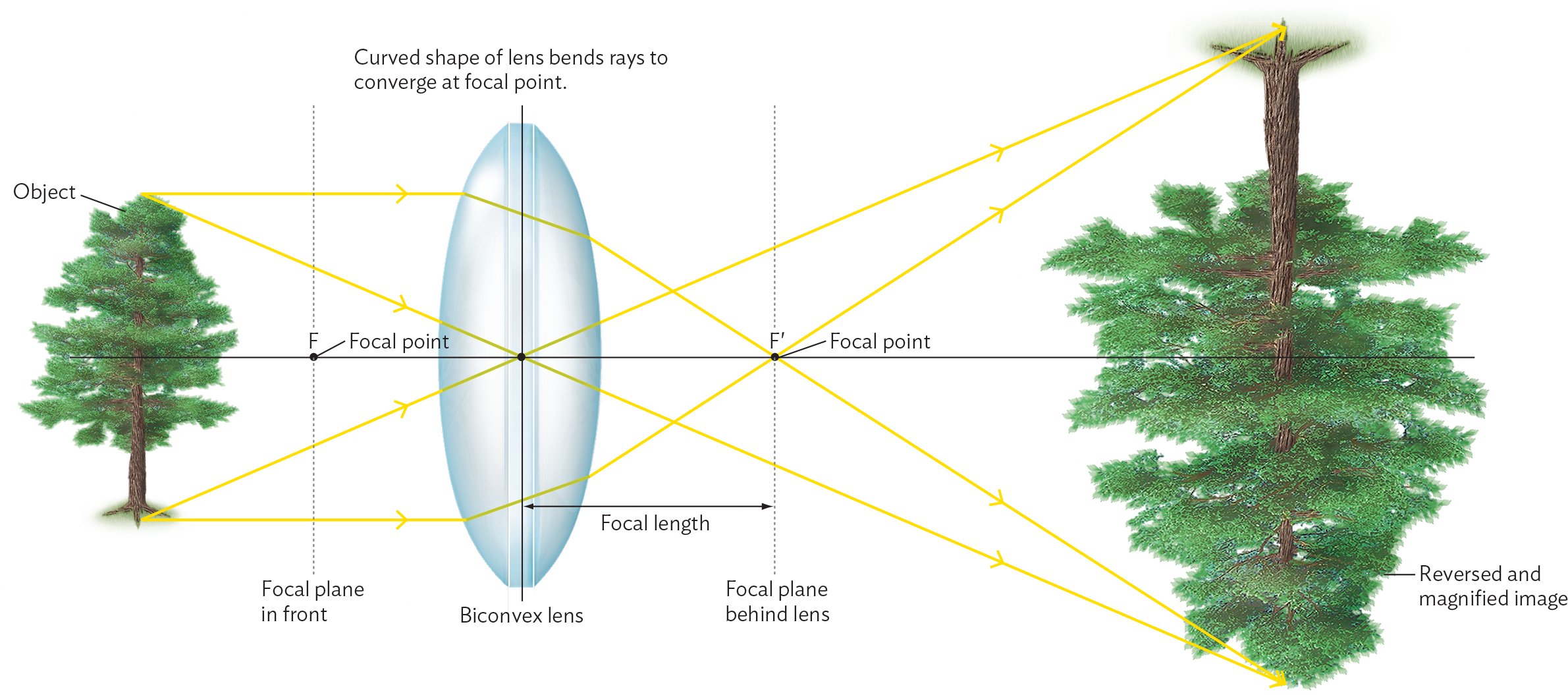

In Figure 3.12, the object under observation is placed just outside the focal plane (a plane containing the focal point of the lens). The lens bends all light rays from the object. Parallel rays converge at the opposite focal point. As the rays continue beyond the focal point, the image rotates 180 degrees, thus appearing upside down, and the inverted image expands, magnified by the spreading out of the refracted rays. The distance between parts of the magnified image is enlarged, enabling our eyes to resolve finer details.

A diagram explaining how an image is generated with a lens. A tree serves as an example object in front of a biconvex lens. The lens consists of two curved pieces of glass connected to form an ovoid shape. There is a focal point in front of and behind the lens. Four light rays from the tree pass through the lens. The two light rays at the middle pass through the lens’s center point, which is reflected above the focal point behind the lens. The top and bottom light rays pass through the lens and converge at the focal point behind the lens. This convergence is caused by the curved shape of the lens. The distance between the lens midline and the focal point is called the focal length. The four light rays lead to a magnified and reversed image of the tree.

How does magnification enable our eyes to see increased resolution? Magnification increases the distance between peaks of light intensity, so that they are detected by separate photoreceptors on your retina (see Figure 3.2). But the resolution of detail in microscopy is limited by the degree to which details “expand” with magnification. The spreading of light rays does not necessarily increase resolution. For example, an image composed of dots does not gain detail when enlarged on a photocopier. In this case, resolution fails to increase because the individual details of the image expand in proportion to the expansion of the overall image. Magnification without an increase in resolution is called empty magnification.

SECTION SUMMARY

Thought Question 3.1 Explain what happens to a refracted light wave as it emerges from a piece of glass of even thickness. How do its new speed and direction compare with its original (incident) speed and direction?

The part of the wavefront that emerges first travels faster than the portion still in the glass, causing the wavefront to bend toward the surface of the glass. Ultimately, the wave travels in the same direction and with the same speed as it did before entering the glass. The path of the emerging light ray is parallel to the path of the light ray entering the glass and is shifted over by an amount dependent on the thickness of the glass. This refraction will alter the path of the light beam.