MLA-e Sample Research Paper

The following report was written by Dylan Borchers for a first-year writing course. It’s formatted according to the guidelines of the MLA (style.mla.org).

Sample Research Paper, MLA Style

Put your last name and the page number in the upper-right corner of each page, ½” from the margin.

1” margins on all sides, beginning with your heading.

Borchers 1

Dylan Borchers

Professor Bullock

English 102, Section 4

4 May 2019

Against the Odds:

Harry S. Truman and the Election of 1948

Double-spaced throughout.

Author named in signal phrase, page numbers in parentheses.

Just over a week before Election Day in 1948, a New York Times article noted “[t]he popular view that Gov. Thomas E. Dewey’s election as President is a foregone conclusion” (Egan). This assessment of the race between incumbent Democrat Harry S. Truman and Dewey, his Republican challenger, was echoed a week later when Life magazine published a photograph whose caption labeled Dewey “The Next President” (Photograph). In a Newsweek survey of fifty prominent political writers, each predicted Truman’s defeat, and Time correspondents declared Dewey would carry 39 of the 48 states (Donaldson 210). Nearly every major US media outlet endorsed Dewey. As historian Robert Ferrell observes, even Truman’s wife, Bess, thought he would lose (270).

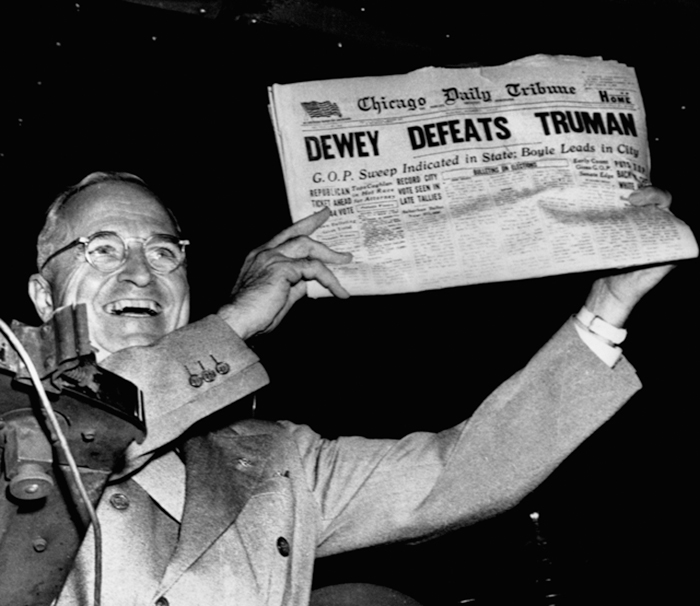

The results of an election are not easily predicted, as is shown in the famous photograph in which Truman holds up a newspaper proclaiming Dewey the victor (fig. 1). Not only did Truman win, but he won by a significant margin: 303 electoral votes and 24,179,259 popular votes to Dewey’s 189 electoral votes and 21,991,291 popular votes (Donaldson 204-07). In fact, many historians and political analysts argue that Truman would have won by an even greater margin had third-party candidates Henry A. Wallace and Strom Thurmond not won votes (McCullough 711). Although

Borchers 2

Illustration is positioned close to the text to which it relates, with figure number and caption with source information.

Truman’s defeat was heavily predicted, those predictions themselves, Dewey’s passiveness as a campaigner, and Truman’s zeal turned the tide for a Truman victory.

No signal phrase; author and page number in parentheses.

In the months preceding the election, public opinion polls predicted that Dewey would win by a large margin. Pollster Elmo Roper stopped polling in September, believing there was no reason to continue, given a seemingly inevitable Dewey landslide. Although the margin narrowed as the election drew near, other pollsters predicted a Dewey win by at least 5 percent (Donaldson 209). Many historians believe that these predictions aided the president. First, surveys showing Dewey in the lead may have prompted some Dewey

Borchers 3

supporters to feel overconfident and therefore to stay home from the polls. Second, the same surveys may have energized Democrats to mount late get-out-the-vote efforts (Lester). Other analysts believe that the overwhelming predictions of a Truman loss kept home some Democrats who saw a Truman loss as inevitable. According to political analyst Samuel Lubell, those Democrats may have saved Dewey from an even greater defeat (Hamby, Man 465). Whatever the impact on the voters, the polls had a decided effect on Dewey.

Paragraphs indent 1/2 inch or 5 spaces.

Two works cited within the same sentence.

Historians and political analysts alike cite Dewey’s overly cautious campaign as a main reason Truman was able to win. Dewey firmly believed in public opinion polls. With all signs pointing to an easy victory, Dewey and his staff believed that all he had to do was bide his time and make no foolish mistakes. Dewey himself said, “When you’re leading, don’t talk” (Smith 30). As the leader in the race, Dewey kept his remarks faultlessly positive, with the result that he failed to deliver a solid message or even mention Truman. Eventually, Dewey began to be perceived as aloof, stuffy, and out of touch with the public. One observer compared him to the plastic groom on top of a wedding cake (Hamby, “Harry S. Truman”), and others noted his stiff, cold demeanor (McCullough 671-74). Through the autumn of 1948, Dewey’s speeches failed to address the issues, with the candidate declaring that he did not want to “get down in the gutter” (Smith 515). When fellow Republicans said he was losing ground, Dewey insisted that his campaign stay the course. Even Time magazine, though it endorsed

Borchers 4

and praised him, conceded that his speeches were dull (McCullough 696). According to historian Zachary Karabell, they were “notable only for taking place, not for any specific message” (244). Dewey’s poll numbers slipped before the election, but he still held a comfortable lead. Truman’s famous whistle-stop campaign would make the difference.

Few candidates in US history have campaigned for the presidency with more passion and faith than Harry Truman. In the autumn of 1948, Truman wrote to his sister, “It will be the greatest campaign any President ever made. Win, lose, or draw, people will know where I stand.” For thirty-three days, he traveled the nation, giving hundreds of speeches from the back of the Ferdinand Magellan railroad car. In the same letter, Truman described the pace: “We made about 140 stops and I spoke over 147 times, shook hands with at least 30,000 and am in good condition to start out again tomorrow.” David McCullough writes of Truman’s campaign:

Quotations of more than 4 lines indented 1/2 inch (5 spaces) and double-spaced.

No President in history had ever gone so far in quest of support from the people, or with less cause for the effort, to judge by informed opinion. . . . As a test of his skills and judgment as a professional politician, not to say his stamina and disposition at age sixty-four, it would be like no other experience in his long, often difficult career, as he himself understood perfectly. (655)

He spoke in large cities and small towns, defending his policies and attacking Republicans. As a former farmer, Truman was able to connect with the public. He developed an energetic

Borchers 5

style, usually speaking from notes rather than from a prepared speech, and often mingled with the crowds, which grew larger as the campaign progressed. In Chicago, over half a million people lined the streets as he passed, and in St. Paul the crowd numbered over 25,000. When Dewey entered St. Paul two days later, only 7,000 supporters greeted him (McCullough 842). Reporters brushed off the large crowds as mere curiosity seekers wanting to see a president (682). Yet Truman persisted, even if he often seemed to be the only one who thought he could win. By connecting directly with the American people, Truman built the momentum to surpass Dewey and win the election.

The legacy and lessons of Truman’s whistle-stop campaign continue to be studied, and politicians still mimic his campaign methods by scheduling multiple visits to key states, as Truman did. He visited California, Illinois, and Ohio 48 times, compared with 6 visits to those states by Dewey. Political scientist Thomas Holbrook concludes that his strategic campaigning in those states and others gave Truman the electoral votes he needed to win (61, 65).

The 1948 election also had an effect on pollsters, who, as Roper admitted, “couldn’t have been more wrong.” Life magazine’s editors concluded that pollsters as well as reporters and commentators were too convinced of a Dewey victory to analyze the polls seriously, especially the opinions of undecided voters (Karabell 256). Pollsters assumed that undecided voters would vote in the same proportion as decided voters—and that turned out to be a false assumption (257). In fact, the

Borchers 6

lopsidedness of the polls might have led voters who supported Truman to call themselves undecided out of an unwillingness to associate themselves with the losing side, further skewing the polls’ results (McDonald et al. 152). Such errors led pollsters to change their methods significantly after the 1948 election.

Many political analysts, journalists, and historians concluded that the Truman upset was in fact a victory for the American people. And Truman biographer Alonzo Hamby notes that “polls of scholars consistently rank Truman among the top eight presidents in American history” (Man 641). But despite Truman’s high standing, and despite the fact that the whistle-stop campaign remains in our political landscape, politicians have increasingly imitated the style of the Dewey campaign, with its “packaged candidate who ran so as not to lose, who steered clear of controversy, and who made a good show of appearing presidential” (Karabell 266). The election of 1948 shows that voters are not necessarily swayed by polls, but it may have presaged the packaging of candidates by public relations experts, to the detriment of public debate on the issues in future presidential elections.

Borchers 7

Donaldson, Gary A. Truman Defeats Dewey. UP of Kentucky, 1999.

Double-spaced.

Alphabetized by authors’ last names.

Each entry begins at the left margin; subsequent lines are indented.

Multiple works by a single author listed alphabetically by title. For subsequent works, replace author’s name with three hyphens.

Egan, Leo. “Talk Is Now Turning to the Dewey Cabinet.” The New York Times, 20 Oct. 1948, p. E8.

Ferrell, Robert H. Harry S. Truman: A Life. U of Missouri P, 1994.

Hamby, Alonzo L. “Harry S. Truman: Campaigns and Elections.” Miller Center, U of Virginia, millercenter.org/president/biography/truman-campaigns-and-elections. Accessed 17 Mar. 2019.

---. Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman. Oxford UP, 1995.

Holbrook, Thomas M. “Did the Whistle-Stop Campaign Matter?” PS: Political Science and Politics, vol. 35, no. 1, Mar. 2002, pp. 59-66.

Karabell, Zachary. The Last Campaign: How Harry Truman Won the 1948 Election. Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

Lester, Will. “‘Dewey Defeats Truman’ Disaster Haunts Pollsters.” Los Angeles Times, 1 Nov. 1998, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1998-nov-01-mn-38174-story.html.

McCullough, David. Truman. Simon and Schuster, 1992.

McDonald, Daniel G., et al. “The Spiral of Silence in the 1948 Presidential Election.” Communication Research, vol. 28, no. 2, Apr. 2001, pp. 139-55.

Photograph of Truman. Life, 1 Nov. 1948, p. 37. Google Books, books.google.com/books?id=ekoEAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false.

Rollins, Byron. Dewey Defeats Truman. 1948. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum, National Archives and Records Administration, www.trumanlibrary.gov/photograph-records/95-187.

Borchers 8

Roper, Elmo. “Roper Eats Crow; Seeks Reason for Vote Upset.” Evening Independent, 6 Nov. 1948, p. 10. Google News, news.google.com/newspapers?nid=PZE8UkGerEcC&dat=19481106&printsec=frontpage&hl=en.

Smith, Richard Norton. Thomas E. Dewey and His Times. Simon and Schuster, 1982.

Every source used is in the list of works cited.

Truman, Harry S. “Campaigning, Letter, October 5, 1948.” Harry S. Truman, edited by Robert H. Ferrell, CQ Press, 2003, p. 91. American Presidents Reference Series.