3.7 Genes: Structural and Regulatory

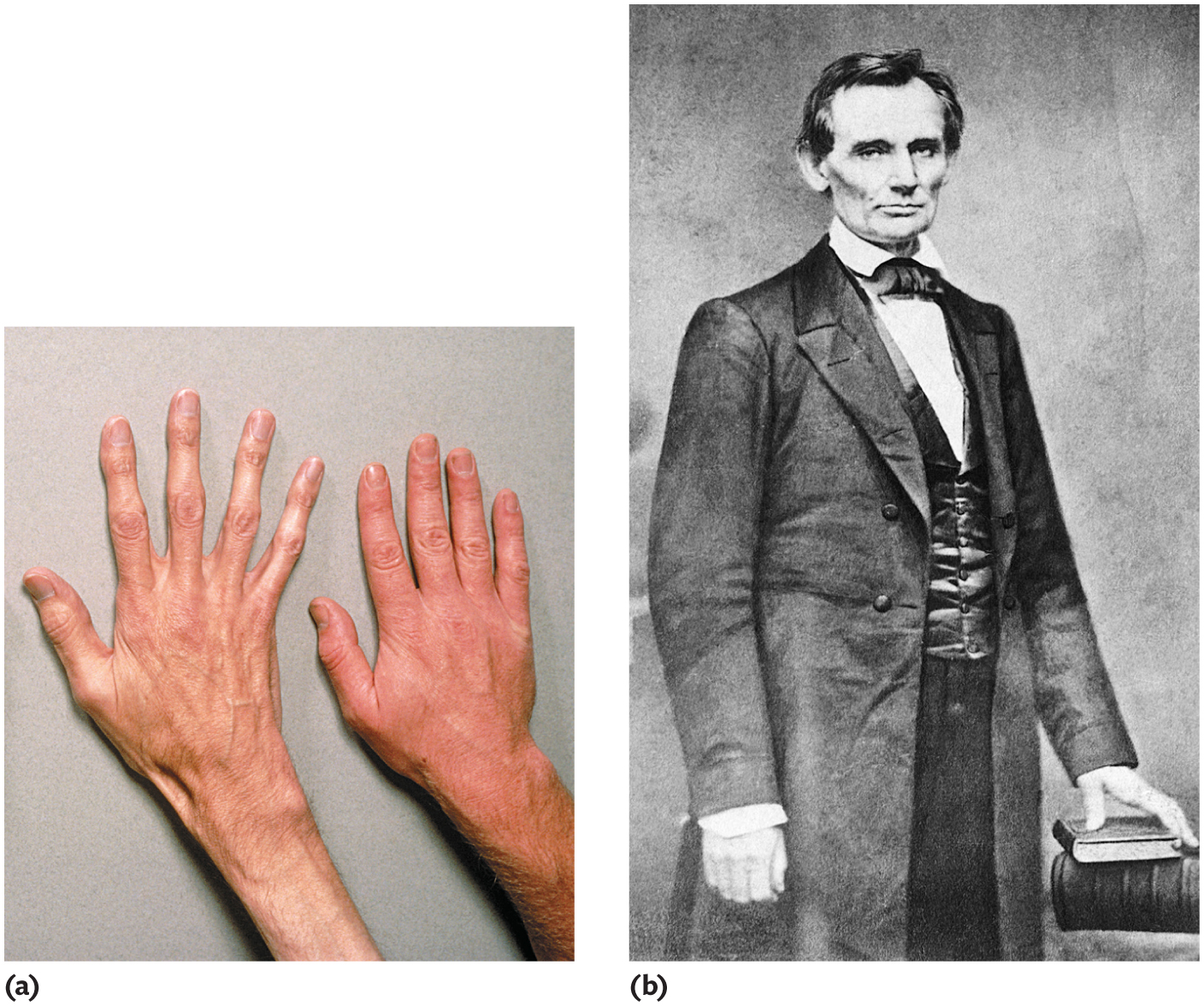

Structural genes are responsible for body structures, such as hair, blood, and other tissues. Regulatory genes turn other genes on and off, an essential activity in growth and development. If the genes that determine bones, for example, did not turn off at a certain point, bones would continue to grow well beyond what would be acceptable for a normal life (Figure 3.20).

Chickens have the genes for tooth development, but they do not develop teeth because those genes are permanently turned off. Humans have a gene for total body hair coverage, but that gene is not turned on completely. The human genes for sexual maturity turn on during puberty, somewhat earlier in girls than in boys. Regulatory genes can lead to lactose intolerance in humans (see “Anthropology Matters: Got Milk? The LCT Phenotype” in chapter 4). In this instance, the LCT gene is turned off for most human populations around the world after weaning, usually by about age 4. However, most humans of northern European and East African descent have inherited a different regulatory gene, which creates lactase persistence. A person who lacks the LCT gene and eats dairy products experiences great gastrointestinal discomfort. A person who retains the gene is able to digest lactose owing to the persistence of lactase, thus enjoying the nutritional benefits of milk.

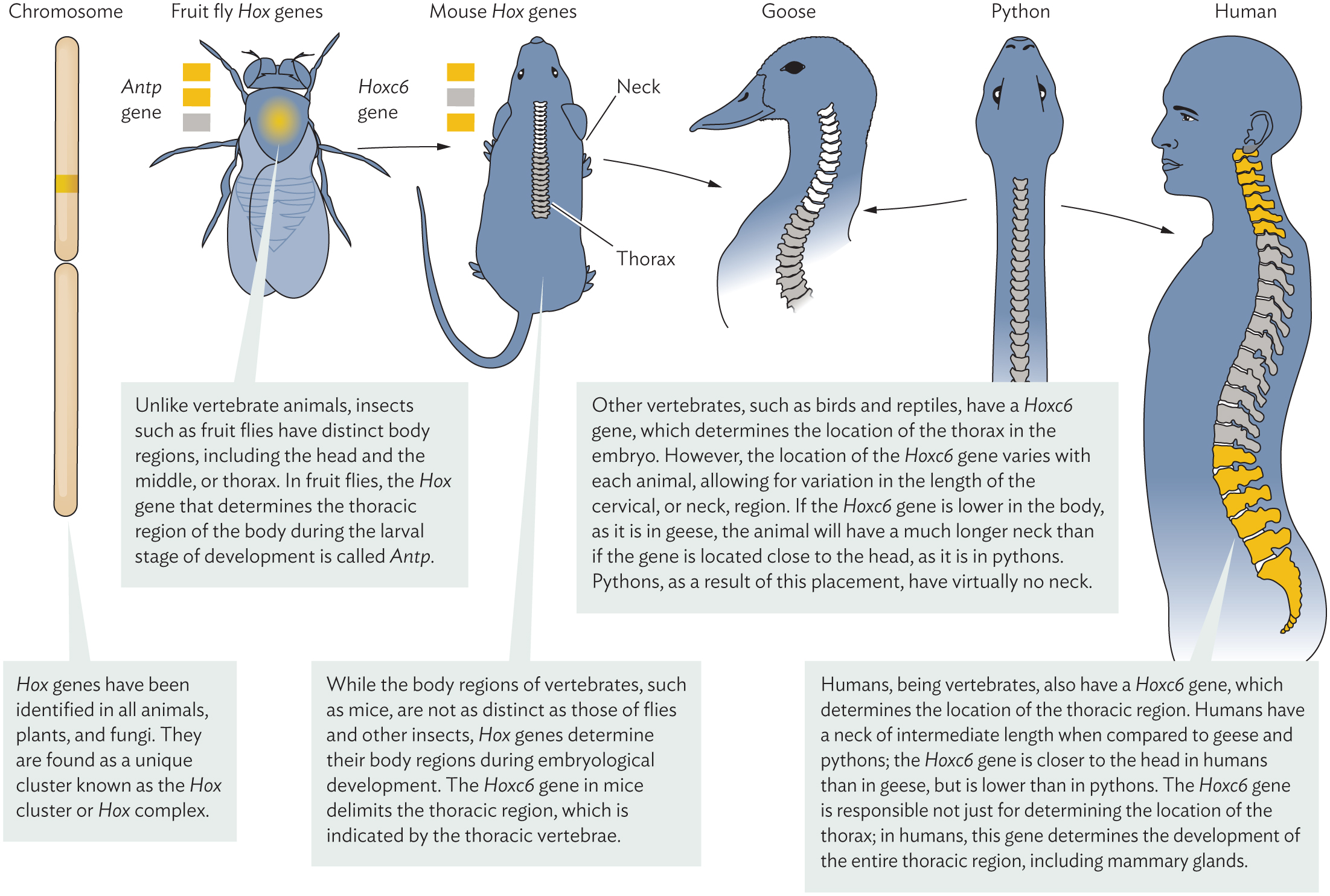

An organism’s form and the arrangement of its tissues and organs are determined by regulatory genes called homeotic (Hox) genes. These master genes guide, for example, the embryological development of all the regions of an animal’s body, such as the head, trunk, and limbs (Figure 3.21). This means that in the process of development, particular sets of Hox genes are turned on in a particular sequence, causing the correct structure or part of a structure to develop in each region. Until recently, scientists thought that the genes that control the development of the key structures and functions of the body differed from organism to organism. We now know, however, that the development of various body parts in complex organisms—such as the limbs, eyes, and vital organs—is governed by the same genes. Hox genes were first found in fruit flies, but research has shown that a common ancestral lineage has given organisms—ranging from flies to mice to humans—the same basic DNA structure in the key areas that control the development of form. Flies look like flies, mice look like mice, and humans look like humans because the Hox genes are turned on and off at different places and different times during the development process.

Glossary

-

Genes coded to produce particular products, such as an enzyme or hormone, rather than for regulatory proteins.

-

Those genes that determine when structural genes and other regulatory genes are turned on and off for protein synthesis.

-

Also known as homeobox genes, they are responsible for differentiating the specific segments of the body, such as the head, tail, and limbs, during embryological development.