Incentives

When Do Price Ceilings Matter?

Price controls attempt to set prices through government regulations in the market. In most cases, and certainly in the United States, price controls are enacted to ease perceived burdens on society. A price ceiling creates a legally established maximum price for a good or service. In the next section, we consider what happens when a price ceiling is in place. Price ceilings create many unintended effects that policymakers rarely acknowledge.

Understanding Price Ceilings

To understand how price ceilings work, let’s try a simple thought experiment. Suppose that most prices are rising as a result of inflation, an overall increase in prices. The government is concerned that people with low incomes will not be able to afford to eat. To help the disadvantaged, legislators pass a law stating that no one can charge more than $0.50 for a loaf of bread. (Note that this price ceiling is about one-third the typical price of a loaf of generic white bread.) Does the new law accomplish its goal? What happens?

More information

A line of people outside of a bakery with the sign: Panaderia y Pasteleria. There is a large pile of garbage in the street.

The law of demand tells us that if the price drops, the quantity that consumers demand will increase. At the same time, the law of supply tells us that the quantity supplied will fall because producers will be receiving lower profits for their efforts. This combination of increased quantity demanded and reduced quantity supplied will cause a shortage of bread.

On the demand side, consumers will want more bread than is available at the legal price. There will be long lines for bread, and many people will not be able to get the bread they want. On the supply side, producers will look for ways to maintain their profits. They can reduce the size of each loaf they produce. They can also use cheaper ingredients, thereby lowering the quality of their product, and they can stop making fancier varieties.

In addition, illegal markets will develop. For instance, in 2014 Venezuela instituted price controls on flour, which has led to severe shortages of bread. In this real-life example, many people who do not want to wait in line for bread or who do not obtain it despite waiting in line will resort to illegal means to obtain it. In other words, sellers will go “underground” and charge higher prices to customers who want bread. Table 6.1 summarizes the likely outcomes of price controls on bread.

TABLE 6.1

A Price Ceiling on Bread

The Effect of Price Ceilings

More information

A young man looks upward while placing his hands over his head as if pushing up an imaginary ceiling.

Now that we have some understanding of how a price ceiling works, we can transfer that knowledge into the supply and demand model for a deeper analysis of how price ceilings affect the market. To explain when price ceilings matter in the short run, we examine two types of price ceilings: nonbinding and binding. Both are set by law, but only one actually makes a difference to prices.

NONBINDING PRICE CEILINGS

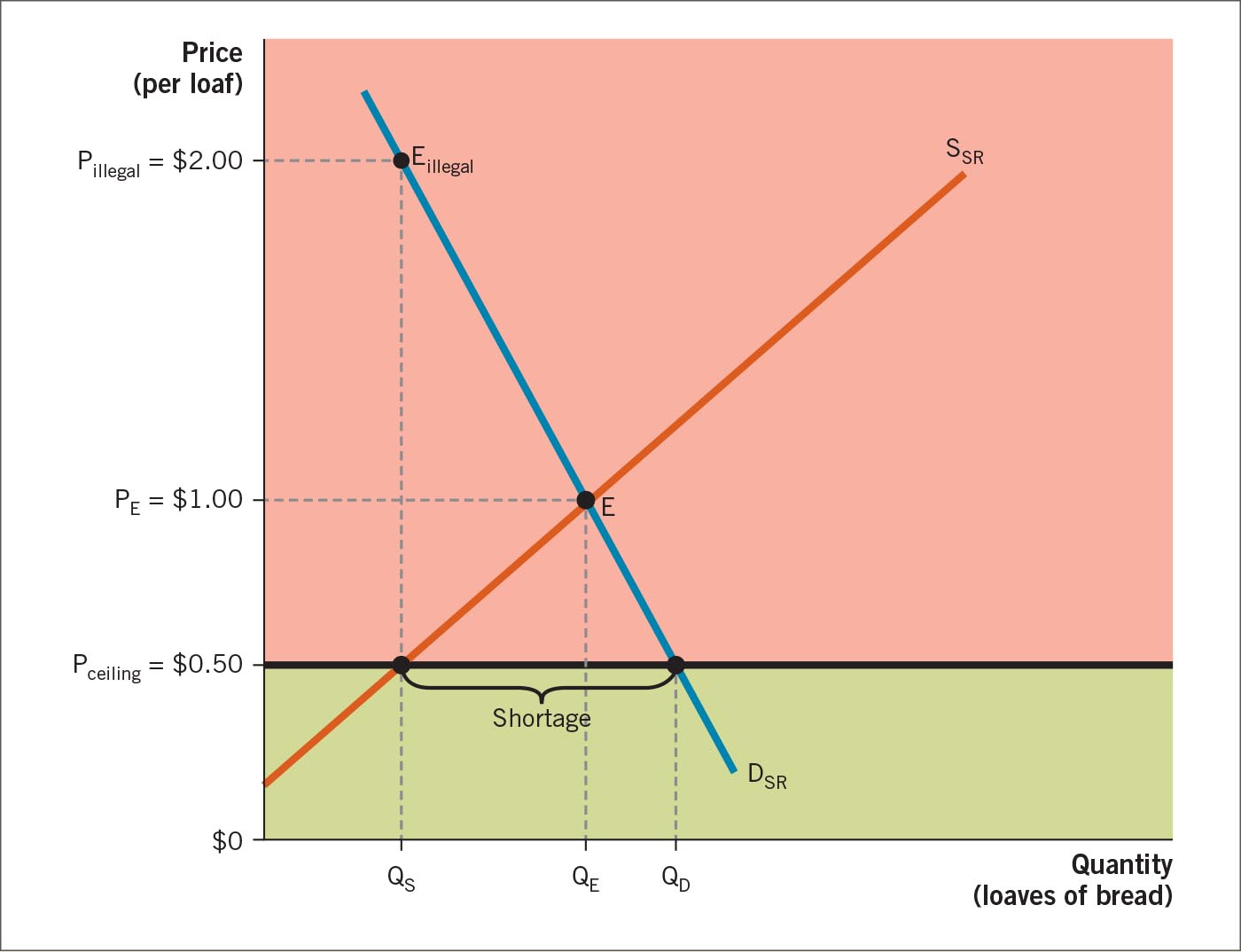

The effect of a price ceiling depends on the level at which it is set relative to the equilibrium price. When a price ceiling is above the equilibrium price, we say it is nonbinding. Figure 6.1 shows a price ceiling of $2.00 per loaf in a market where $2.00 is above the equilibrium price (PE) of $1.00. All prices at or below $2.00 (the green area) are legal. Prices above the price ceiling (the red area) are illegal. But because the market equilibrium (E) occurs in the green area, the price ceiling does not influence the market; it is nonbinding. As long as the equilibrium price remains below the price ceiling, price will continue to be regulated by supply and demand.

BINDING PRICE CEILINGS

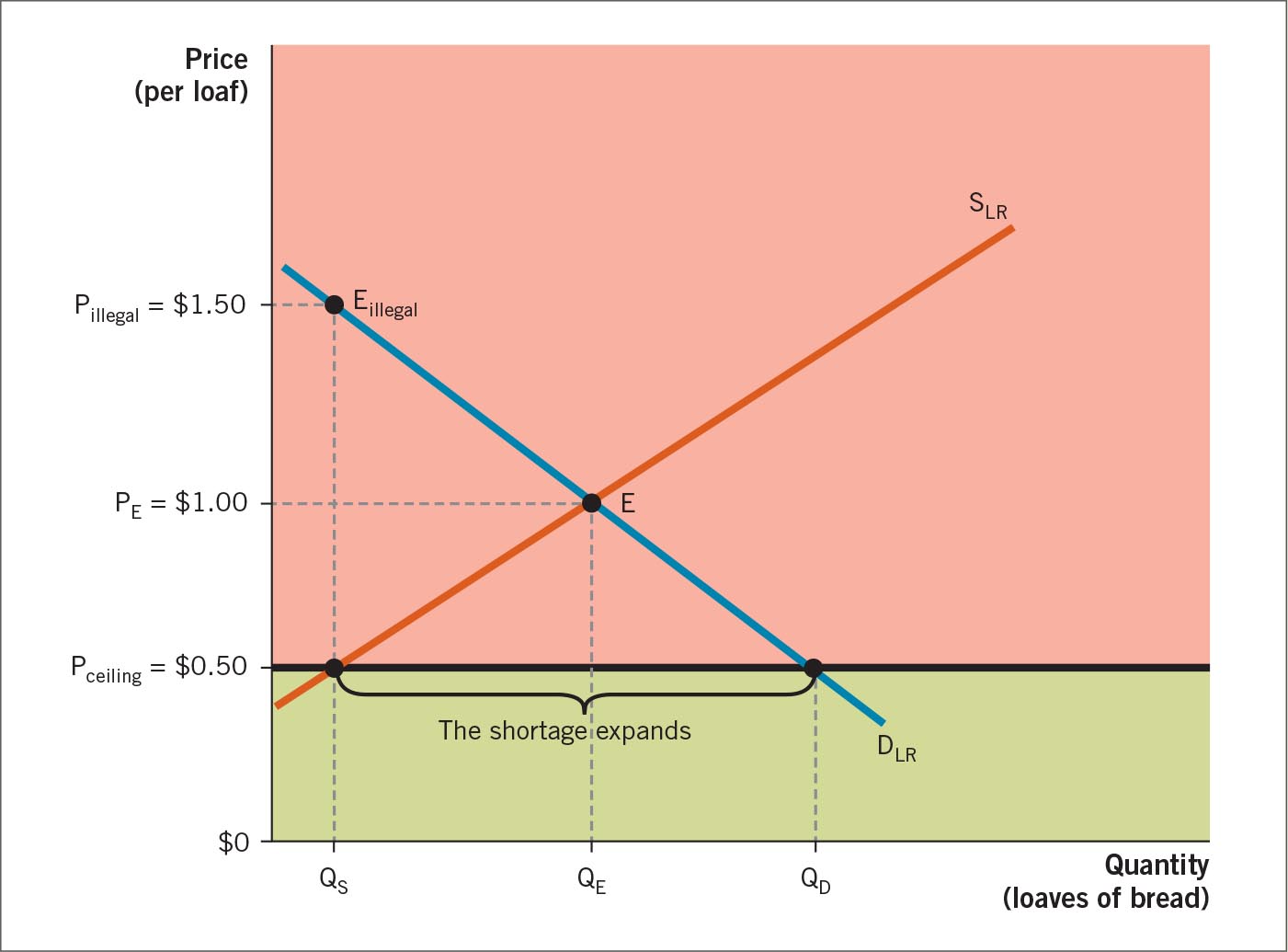

When a price ceiling is below the market price, it creates a binding constraint that prevents supply and demand from clearing the market. In Figure 6.2, the price ceiling for bread is set at $0.50 per loaf. Because $0.50 is well below the equilibrium price of $1.00, the price ceiling is binding. Notice that at a price of $0.50, the quantity demanded (QD) is greater than the quantity supplied (QS); in other words, a shortage exists. Shortages typically cause prices to rise, but the imposed price ceiling prevents that from happening. A price ceiling of $0.50 allows only the prices in the green area. The market cannot reach the equilibrium point E at $1.00 per loaf because it is located above the price ceiling, in the red area.

Incentives

The illegal price is also set by supply and demand. Because prices above $0.50 are illegal, sellers are unwilling to produce more than QS. Because a shortage exists, this market will form in response to the shortage. Here, purchasers can illegally resell what they have just bought at $0.50 for far more than what they just paid. Because the supply of legally produced bread is QS, the intersection of the vertical dashed line that reflects QS with the demand curve DSR at point Eillegal establishes a market price (Pillegal) at $2.00 per loaf for illegally sold bread. The market price is substantially more than the market equilibrium price (PE) of $1.00. As a result, the price in these illegal markets eliminates the shortage caused by the price ceiling. However, the price ceiling has created two unintended consequences: a smaller quantity of bread supplied (QS is less than QE), and a higher price for those who purchase it there.

Price Ceilings in the Long Run

In the long run, supply and demand become more elastic, or flatter. Recall from Chapter 4 that when consumers have additional time to make choices, they find more ways to avoid high-priced goods and more ways to take advantage of low prices. Additional time also gives producers the opportunity to produce more when prices are high and less when prices are low. In this section, we consider what happens if a binding price ceiling on bread remains in effect for a long time. We have already observed that binding price ceilings create shortages and illegal markets in the short run. Are the long-run implications of price ceilings more problematic or less problematic than the short-run implications? Let’s find out by looking at what happens to both supply and demand.

FIGURE 6.1

A Nonbinding Price Ceiling

The price ceiling ($2.00) is set above the equilibrium price ($1.00). Because market prices are set by the intersection of supply (S) and demand (D), as long as the equilibrium price is below the price ceiling, the price ceiling is nonbinding and has no effect.

More information

A nonbinding price ceiling on the market for bread. On the y axis is price per loaf, and on the x axis is quantity of loaves of bread. The supply curve is linear with a positive slope, and the demand curve is linear with a negative slope. The supply and demand curve cross at the equilibrium point E, where the equilibrium price is upper P subscript E equals one dollar and equilibrium quantity is upper Q subscript E. A price ceiling is set at 2 dollars represented by a horizontal line that intersects the supply and demand curves.

FIGURE 6.2

The Effect of a Binding Price Ceiling in the Short Run

A binding price ceiling prevents sellers from increasing the price and causes them to reduce the quantity they offer for sale. As a consequence, prices no longer signal relative scarcity. Consumers desire to purchase the product at the price ceiling level, which creates a shortage in the short run (SR); many will be unable to obtain the good. As a result, those who are shut out of the market will turn to other means to acquire the good, establishing an illegal market for it at a higher, illegal price.

More information

A binding price ceiling on the market for bread. On the y axis is price per loaf, and on the x axis is quantity of loaves of bread. In the short run, the supply and demand curves are relatively steep, and the shortage created is relatively small.

Figure 6.3 shows the result of a price ceiling that remains in place for a long time. Here the supply curve is more elastic than its short-run counterpart in Figure 6.2. The supply curve is flatter because producers respond in the long run by producing less bread and converting their facilities to make similar products that are not subject to price controls and that will bring them a reasonable return on their investments—for example, bagels and rolls. Therefore, in the long run the quantity supplied (QS) shrinks even more.

The demand curve is also more elastic (flatter) in the long run. In the long run, more people will attempt to take advantage of the price ceiling by changing their eating habits to consume more bread. Even though consumers will often find empty shelves in the long run, the quantity demanded of cheap bread will increase. The flatter demand curve means that consumers are more flexible. As a result, the quantity demanded (QD) expands and bread is harder to find at $0.50 per loaf. The shortage will become so acute (compare Figure 6.3 with Figure 6.2) that consumers will turn to bread substitutes, like bagels and rolls, that are more plentiful because they are not price controlled.

FIGURE 6.3

The Effect of a Binding Price Ceiling in the Long Run

In the long run (LR), increased elasticity on the part of both producers and consumers makes the shortage larger than it was in the short run. Consumers adjust their demand to the lower price and want more bread. Producers adjust their supply and make less of the unprofitable product. As a result, the product becomes progressively harder to find.

More information

A binding price ceiling on the market for bread. On the y axis is price per loaf, and on the x axis is quantity of loaves of bread. The long run supply curve, upper S subscript L R, is linear with a positive slope, and the long run demand curve, upper D subscript L R, is linear with a negative slope. The supply and demand curve cross at the equilibrium point E, where the equilibrium price is upper P subscript E equals one dollar and equilibrium quantity is upper Q subscript E. A price ceiling, upper P subscript ceiling, is set at 50 cents, and is a horizontal line that intersects the supply curve at the quantity supplied, upper Q subscript S, and the demand curve at the quantity demanded, upper Q subscript D. Point upper subscript illegal is at 1 dollar and 50 cents on the y axis at a quantity of upper Q subscript S.

ECONOMICS in the MEDIA

Price Ceilings

Price Ceilings in Slumdog Millionaire

Price Ceilings in Slumdog Millionaire

SLUMDOG MILLIONAIRE

More information

A winding dirt road forms the city street of a slum lined with clusters small shacks.

The setting for the Academy Awards’ Best Picture of 2008 is Mumbai, India. Eighteen-year-old Jamal Malik is an Indian Muslim who is a contestant on the Indian version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? Dharavi, where the film is set, is a Mumbai slum about half the size of New York’s Central Park. Over 1 million people call Dharavi home. Malik is one question away from the grand prize. However, he is detained by the authorities, who suspect him of cheating because they cannot comprehend how a “slumdog” could know all the answers. The movie beautifully chronicles the events in Jamal’s life that provided him with the answers. Jamal, contrary to the stereotype of the people that live in the Dharavi slum, is intelligent, entrepreneurial, and fully capable of navigating life in the 21st century.

Rent controls have existed in Mumbai since 1947. Under the Rents, Hotel and Lodging House Rates Control Act, the government placed a cap on the amount of rent a tenant pays to a landlord. This limit has remained virtually frozen despite the consistent rise in market prices over time. As economists, we know that this policy will create excess demand. Renters are lined up for housing, and therefore, landlords can offer substandard accommodations and still have many takers. When this process continues for generations, as it has in Mumbai, the cumulative effect is that many buildings are unsafe to live in.

Price ceilings set the regulated price below the market equilibrium price determined by supply and demand. As a result, there is an increase in the quantity demanded. At the same time, since the price that landlords can charge is below the market equilibrium price, many landlords have left the apartment market to sell and invest elsewhere. As a consequence, the supply of rental units is reduced over time, which leads to long wait lists for apartments. Since the quantity demanded exceeds the quantity supplied, some landlords also impose additional requirements on potential tenants, leading to discrimination against certain groups of people.

Increased elasticity on the part of producers and consumers magnifies the unintended consequences we observed in the short run. Therefore, products subject to a price ceiling become progressively harder to find in the long run and the illegal market continues to operate. However, in the long run our bread consumers will choose substitutes for this expensive bread, leading to somewhat lower prices in the long run.

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

Price Ceilings: Ridesharing

More information

Two people sharing a phone.

QUESTION: Surge pricing is the practice of raising prices during periods of increased demand, sometimes for just a few hours at a stretch. Suppose that users of rideshare services, such as Lyft and Uber, persuade Congress to ban surge pricing when emergencies are declared. How will this policy affect the number of people who can use ridesharing in times of crisis?

Glossary

- Price controls

- Price controls attempt to set prices through government regulations in the market.

- price ceiling

- A price ceiling is a legally established maximum price for a good or service.

ANSWER

ANSWER ANSWER:

ANSWER: