Handling Negative Externalities through Taxes and Regulations

What Are Externalities, and How Do They Affect Markets?

We have seen that buyers and sellers benefit from trade. But what about the effects trade might have on bystanders? Externalities, or the costs and benefits of a market activity that affect a third party, often lead to undesirable consequences. Market failure occurs when there is an inefficient allocation of resources in a market. Externalities are a type of market failure. For example, in 2023, a Norfolk Southern Railway train containing toxic chemicals derailed near the town of East Palestine, Ohio, spilling its contents into the water and emitting pollutants into the air. Overall, the damage to property and human health amounted to hundreds of millions of dollars. Even though Norfolk Southern and the companies using these chemicals to make plastic stood to benefit from shipments like this one, in this case, the citizens living in this area had their lives severely disrupted. Property values plummeted, and people moved away permanently as a result of the chemical spill.

For a market to work as efficiently as possible, two things must happen. First, each participant must be able to evaluate the internal costs of participation—the costs that only the individual participant pays. For example, when we choose to drive somewhere, we typically consider our internal (also known as personal) costs—the time it takes to reach our destination, the amount we pay for gasoline, and what we pay for routine vehicle maintenance. Second, for a market to work efficiently, the external costs must also be paid. External costs are the costs of a market activity imposed on people who are not participants in that market. In the case of driving, the congestion and pollution our cars create are external costs. Economists define social costs as the sum of the internal costs and external costs of a market activity.

In this section, we consider some of the mechanisms that encourage consumers and producers to account for the social costs of their actions.

The Third-Party Problem

An externality exists whenever an internal cost (or benefit) diverges from a social cost (or benefit). For example, manufacturers who make vehicles and consumers who purchase them benefit from the transaction, but making and using those vehicles lead to externalities—including air pollution and traffic congestion—that adversely affect others. A third-party problem occurs when those not directly involved in a market activity experience negative or positive externalities.

If a third party is adversely affected, the externality is negative. For example, a negative externality occurs when the number of vehicles on the roads causes air pollution. Negative externalities present a challenge to society because it is difficult to make consumers and producers take responsibility for the full costs of their actions. For example, drivers typically consider only the internal costs (their own costs) of reaching their destination. Likewise, manufacturers generally prefer to ignore the pollution they create, because addressing the problem would raise their costs without providing them with significant direct benefits.

In general, society would benefit if all consumers and producers considered both the internal and external costs of their actions. Given most people feel this expectation is unlikely to happen, governments design policies that create incentives for firms and people to limit the amount of pollution they emit.

An effort by the city government of Washington, D.C., shows the potential power of this approach. Like many communities throughout the United States, the city instituted a 5-cent tax on every plastic bag a consumer picks up at a store. While 5 cents may not sound like much of a disincentive, shoppers have responded by switching to cloth bags or reusing plastic ones. In Washington, D.C., the number of plastic bags used every month fell from 22.5 million in 2009 to 3 million in 2018, significantly reducing the amount of plastic waste entering landfills in the process.

Not all externalities are negative, however. For instance, education creates a large positive externality for society beyond the benefits to individual students, teachers, and support staff. A more knowledgeable workforce benefits employers looking for qualified employees and is more efficient and productive than an uneducated workforce. And because local businesses experience a positive externality from a well-educated local community, they have a stake in the educational process.

A good example of the synergy between local business and higher education is California’s Silicon Valley, which is home to many high-tech companies and Stanford University. As early as the late nineteenth century, Stanford’s leaders felt that the university’s mission should include fostering the development of self-sufficient local industry. After World War II, Stanford encouraged faculty and graduates to start their own companies, which led to the creation of Hewlett-Packard, Bell Labs, and Xerox. A generation later, this nexus of high-tech firms gave birth to leading software and Internet firms like 3Com, Adobe, Facebook, and Snapchat, and—more indirectly—Cisco, Apple, and Alphabet.

Recognizing the benefits they received, many of the most successful businesses associated with Stanford have donated large sums to the university. For instance, the Hewlett Foundation gave $400 million to Stanford’s endowment for the humanities and sciences and for undergraduate education—an act of generosity that highlights the positive externality Stanford University had on Hewlett-Packard.

And sometimes, an externality is best dealt with through compromise. Consider Venice, which typically has 25 million visitors a year. Modern cruise ships traversing the Guidecca Canal into Venice’s lagoon tower over the buildings, and, critics say, the waves from the ships have been accelerating the erosion of the city’s fourteenth-century buildings, which are built on shallow and unstable mudbanks. These tourists spend a lot of money in Venice, though, and local businesses have fought to keep the big ships coming into the lagoon. When cruise ship travel halted during the pandemic, opponents had a window to suggest alternatives and emphasize that keeping cruise ships out of the lagoon would help preserve Venice’s status as a World Heritage site. In August of 2021, Italy moved to ban large cruise ships from sailing into the city center. They will be diverted to the industrial port of Marghera, whereas smaller cruise ships can continue to reach the heart of the city.

CORRECTING FOR NEGATIVE EXTERNALITIES

In this section, we explore ways to correct for negative externalities. To do so, we use supply and demand analysis to understand how the externalities affect the market. Let’s begin with supply and compare the difference between what market forces produce and what is best for society in the case of an oil refinery. A refinery converts crude oil to gasoline. This complex process generates many negative externalities, including the release of pollutants into the air and the dumping of waste by-products.

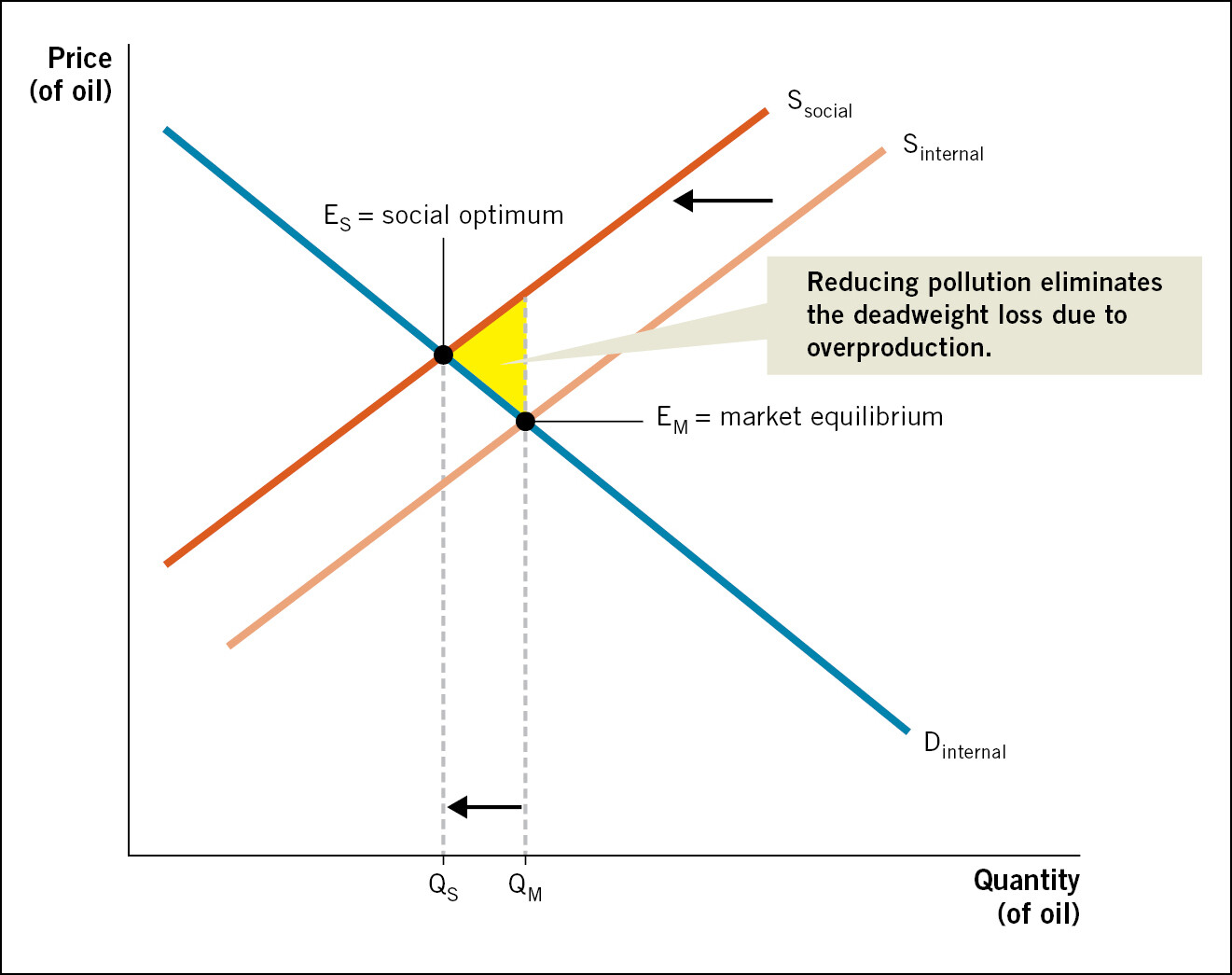

Figure 7.1 illustrates the contrast between the market equilibrium and the social optimum in the case of an oil refinery. The social optimum is the price and quantity combination that would exist if there were no externalities. The supply curve Sinternal represents how much the oil refinery will produce if it does not have to pay for the negative consequences of its activity. In this situation, the market equilibrium, EM, accounts only for the internal costs of production.

When a negative externality occurs, the government may be able to restore the social optimum by requiring externality-causing market participants to pay for the cost of their actions. In this case, there are three potential solutions. First, the refinery can be required to install pollution abatement equipment or change production techniques to reduce emissions and waste by-products. Second, the government can levy a tax on the refinery as a disincentive to produce. Finally, the government can require the firm to pay for any environmental damage it causes. Each solution forces the firm to internalize the externality, meaning that the firm must take into account the external costs (or benefits) to society that occur as a result of its actions.

Having to pay the costs of imposing pollution on others reduces the amount of the pollution-causing activity. This result is evident in the shift of the supply curve to Ssocial. The new supply curve reflects a combination of the internal and external costs of producing the good. Because each corrective measure requires the refinery to spend money to correct the externality and therefore increases overall costs, the willingness to sell the good declines, or shifts to the left. The result is a social optimum at a lower quantity, QS, than at the market equilibrium quantity demanded, QM. The trade-off is clear. We can reduce negative externalities by requiring producers to internalize the externality. However, doing so does not come without cost. Because the supply curve shifts to the left, the quantity produced is lower and the price rises. In the real world, there is always a cost.

In addition, when an externality occurs, the market equilibrium creates deadweight loss, as shown by the yellow triangle in Figure 7.1. In Chapter 5, we considered deadweight loss in the context of government regulation or taxation. These measures, when imposed on efficient markets, create deadweight loss, or an undesirable amount of economic activity. In the case of a negative externality, the market is not efficient because it is not fully capturing the cost of production. Once the government intervenes and requires the firm to internalize the external costs of its production, output falls to the socially optimal level, QS, and the deadweight loss from overproduction is eliminated.

Table 7.1 outlines the basic decision-making process that guides private and social decisions. Private decision-makers consider only their internal costs, but society as a whole experiences both internal and external costs. To align the incentives of private decision-makers with the interests of society, we must find mechanisms that encourage the internalization of externalities.

| Personal decision | Social optimum | The problem | The solution |

| Based on internal costs | Social costs = internal costs plus external costs | To get consumers and producers to take responsibility for the externalities they create | Encourage consumers and producers to internalize externalities |

ECONOMICS in the REAL WORLD

Express Lanes Use Dynamic Pricing to Ease Congestion

Metro Washington, D.C., is notorious for traffic, especially on the Capital Beltway (Interstate 495). New express lanes keep traffic moving by using dynamic pricing, which adjusts tolls based on real-time traffic conditions. Dynamic pricing helps manage the quantity demanded and keeps motorists moving at highway speeds. I-495 express-lane tolls can range from as low as $0.20 per mile during less busy times to approximately $1.25 per mile in some sections during rush hour. The higher rush-hour rates are designed to ensure that the express lanes do not become congested. Motorists thus have a choice: pay more to use the express lanes and arrive faster, or use the regular lanes and arrive later. The decision about whether to use the express lanes is all about opportunity cost. High-opportunity-cost motorists regularly drive the express lanes, while others with lower opportunity costs avoid the express lanes.

Because dynamic prices become part of a motorist’s internal costs, they cause motorists to weigh the costs and benefits of driving into congested areas. In addition, the dynamic pricing of express lanes causes motorists to make marginal adjustments in terms of the time when they drive. High-demand times, such as the morning and evening rush, see higher tolls for using the express lanes and also longer waits in the regular lanes. Faced with either sitting in traffic (if they don’t pay the toll) or being charged more to enter the express lanes at peak-demand times, many motorists attempt to use the Beltway at off-peak times. Since drivers internalize the external costs as a result of the dynamic toll prices even more precisely, the traffic flow spreads out over the course of the day, so the existing road capacity is used more efficiently.

CORRECTING FOR POSITIVE EXTERNALITIES

Positive externalities, like those that result from vaccines, are the result of economic activities that have benefits for third parties. As with negative externalities, economists use supply and demand analysis to compare the efficiency of the market with the social optimum. This time, we focus on the demand curve. Consider a person who gets a flu shot. When the vaccine is administered, the recipient is immunized, which creates an internal benefit. But there is also an external benefit. Because the recipient likely will not come down with the flu, fewer other people will catch the flu and become contagious, which helps to protect even those who do not get flu shots. Therefore, we can say that vaccines provide a positive externality to the rest of society.

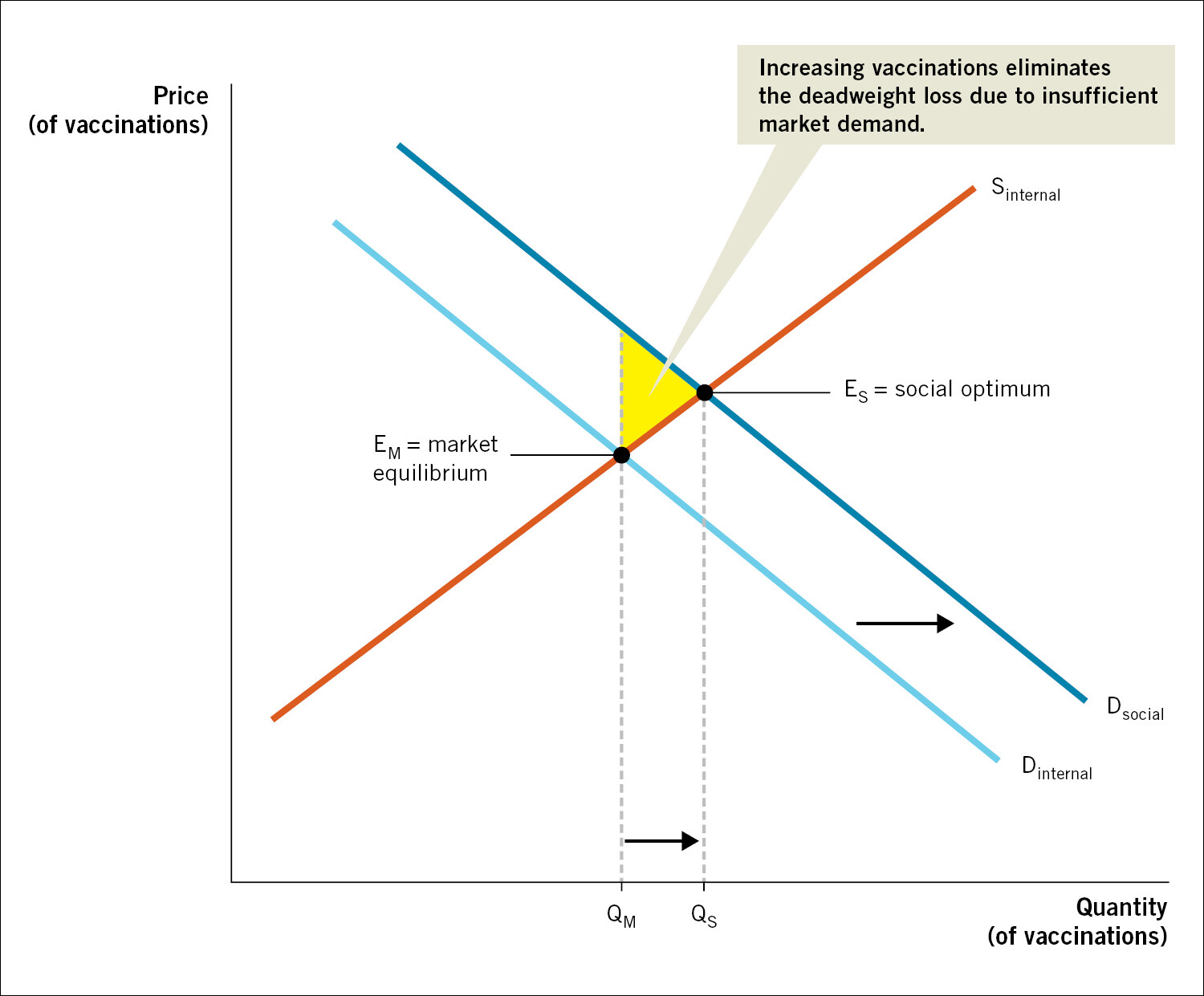

Why do positive externalities exist in the market? Using our example of flu shots, there is an incentive for people in high-risk groups to get vaccinated for the sake of their own health. In Figure 7.2, we capture this internal benefit in the demand curve labeled Dinternal. However, the market equilibrium, EM, only accounts for the internal benefits of individuals deciding whether to get vaccinated. To maximize the health benefits for everyone, public health officials need to find a way to encourage people to consider the external benefit of their vaccination, too. For instance, making flu shots mandatory for hospital staff and other healthcare workers produces positive benefits for all members of society, by internalizing the externality, and helps nudge the market toward the socially optimal number of vaccinations.

Despite the benefits, however, vaccination rates in the United States have been steadily falling for years. The lower vaccination rate led to an outbreak of measles at Disneyland in California in late 2014, where it was believed a foreign visitor introduced the disease and unvaccinated children were exposed to it. The outbreak eventually spread to six U.S. states, Mexico, and Canada—demonstrating just how quickly measles can spread when the vaccination rate is not 100%. This disease continues to be a problem worldwide, with outbreaks in the United States in 2019 and 2024 and much larger ones in 2023 in countries like Yemen, India, and Russia.*

Governments routinely provide free or reduced-cost vaccines to those most at risk from flu and to their caregivers. Because the subsidy enables consumers to spend less money, their willingness to get the vaccine increases, shifting the demand curve in Figure 7.2 from Dinternal to Dsocial. The social demand curve reflects the sum of the internal and external benefits of getting the vaccination. In other words, the subsidy encourages consumers to internalize the externality. As a result, the output moves from the market equilibrium quantity demanded, QM, to a social optimum at a higher quantity, QS.

ECONOMICS at WORK

Using the Big Lessons of Economics at Work

Chava Kornfeld is a graduate of the University of Arizona with a bachelor‘s degree in economics. She now works as an Associate Manager for Business Management for the National Basketball Association (NBA), where she finds she will “apply economics principles daily.” She is on the business development side, selling league-level partnerships in the Marketing & Media department, and generally supporting her group as it creates new opportunities for revenue growth.

Chava says that her “background in economics plays a foundational role” in the way that she approaches her work. She uses economics concepts to analyze market trends, evaluate business competitors, and think about how they can structure and position the pitches they make to potential customers. Her training in the quantitative side of economics helps her “build and use models of revenue,” and translate complex situations, information, and data into “compelling business insights.”

Chava suggests that current students take a broad approach to the lessons of a discipline, focusing “less on memorizing graphs and more on understanding the intuition behind them.” Echoing the foundational concepts emphasized in this text, she notes some of the big lessons she took from her Principles of Economics classes were about “learning how people, businesses, and markets make decisions under constraints. If you can grasp why incentives matter, how trade-offs work, and what happens when conditions change, you'll carry that way of thinking into any field, whether it‘s business, policy, media, or everyday life.” This includes looking at job opportunities in your career. When she chose to move from another firm to the NBA, she says “it was an economics-based decision. Thinking in terms of trade-offs, incentives, and long-term value helped me make a clearer, more confident choice.”

Markets do not handle externalities well. With a negative externality, the market produces too much of a good. But in the case of a positive externality, the market produces too little. In both cases, the market equilibrium creates deadweight loss. When positive externalities are present, the private market is not efficient because it is not fully capturing the social benefits. In other words, the market equilibrium does not maximize the gains for society as a whole. When positive externalities are internalized, the demand curve shifts outward and output rises to the socially optimal level, QS. The deadweight loss that results from insufficient market demand, and therefore underproduction, is eliminated.

Table 7.2 summarizes the key characteristics of positive and negative externalities and presents additional examples of each type.

Handling Positive Externalities through Subsidies

Before moving on, it is worth noting that not all externalities warrant corrective measures. There are times when the size of the externality is negligible and does not justify the cost of increased regulations, charges, taxes, or subsidies that might achieve the social optimum. Because corrective measures have costs, the presence of negligible externalities does not by itself imply that the government should intervene in the market. For instance, some people have strong body odor. This does not mean that the government needs to force everyone to shower regularly. Persons with bad body odor are the exception, and they have every reason to shower, use extra-strength deodorant, or use cologne to mask the smell on their own. If they choose not to avail themselves of these options, they’ll be ostracized in many social situations. Because the magnitude of the negative externality is small and government regulations to completely eliminate the externality would be quite onerous, it is best to leave well enough alone.

ECONOMIC INTUITION INTERACTIVE

PRACTICE WHAT YOU KNOW

Externalities: Artificial Intelligence

AI: Friend or foe? Use your economics skills to answer these questions about AI.

QUESTION: Many companies are either using or experimenting with AI-powered automation. Describe how this might be considered both a positive and a negative externality affecting individuals and communities.

AI-powered assembly line robots do sometimes put human workers out of work. Lost jobs for individuals, and potentially economic hardship for communities that rely on those jobs, can be seen as a negative externality. But there can be positive externalities, such as freeing people from jobs that are highly repetitive, uninteresting, or unsafe. Employees might not lose their jobs but be allowed to focus more on the “better” parts of the job.

QUESTION: AI technology is getting better and better at creating custom photos, imagery, and video content. What are several ways this could lead to positive externalities, and negative externalities?

Positive Externality: For many small and larger companies, as well as creative individuals, creating these custom images are a money- and time-saver. Instead of having to go through expensive and time-intensive creative processes, this material is generated automatically. Small companies or individuals might be able to produce results they could not previously create.

Negative Externality: If your job or your income comes from creating this replaced material, you are experiencing a negative externality. AI also can be used to create false realities that are hard for others to discern as being not real. AI can create “deepfakes” of images, videos, and audio that create false narratives that harm individuals. The widespread creation and dissemination of realistic but false content can erode public trust in shared information sources.

CHALLENGE QUESTION: As AI systems become more sophisticated and more embedded into our daily lives, what are some ways we might balance the economic and social benefits of AI against negative consequences such as job displacement, ethical dilemmas, and the erosion of human creativity and cognitive skills?

This is a tough and ongoing question! Today, we see different types of answers being explored. For example:

- Societies can establish standards and frameworks for data privacy, algorithmic transparency, and ethical AI development, guarding against misuse and bias.

- Investment in education and training programs can prepare workers for jobs that complement AI instead of competing with it. People can be taught skills on how to use AI to enhance decision-making and encourage and value traits like entrepreneurship, human creativity, and critical thinking, ensuring that AI serves as a tool to enhance, not replace, these essential skills.

- AI might be used to provide new thinking and solutions around difficult social problems, healthcare challenges, and challenges with the environment. AI might broaden access to information and be used as an assistant rather than a replacement.

Glossary

- Externalities are the costs or benefits of a market activity that affect a third party.

- Market failure occurs when there is an inefficient allocation of resources in a market.

- Internal costs are the costs of a market activity paid only by an individual participant.

- External costs are the costs of a market activity imposed on people who are not participants in that market.

- A third-party problem occurs when those not directly involved in a market activity experience negative or positive externalities.

- Firms internalize an externality when they take into account the external costs (or benefits) to society that occur as a result of their actions.

Endnotes

- “Current Measles Outbreaks,” Public Health, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Library, https://libguides.mskcc.org.Return to reference *

ANSWER

ANSWER ANSWER:

ANSWER: