Learning Objectives

- Explain how genes are transmitted from parents to offspring.

- Discuss the goals and methods of behavioral genetics.

- Explain how environmental factors, including experience, influence genetic expression.

So far, this chapter has presented the basic biological processes underlying psychological functions. This section considers how genes and environment affect psychological functions. From the moment of conception, we receive the genes we will possess for the remainder of our lives, but to what extent do those genes determine our thoughts and behaviors? How do environmental influences, such as the families and cultures in which we are raised, alter how our brains develop and change?

Until recently, genetic research focused almost entirely on whether people possessed certain types of genes, such as genes for psychological disorders or for particular levels of intelligence. Although it is important to discover the effects of individual genes, this approach misses the critical role of our environment in shaping who we are. Research has shown that environmental factors can affect gene expression—whether a particular gene is turned on or off. Environmental factors may also influence how a gene, once turned on, influences our thoughts, feelings, and behavior. Genetic predispositions also influence the environments people select for themselves. Once again, biology and environment mutually influence each other. All the while, biology and environment—one’s genes and every experience one ever has—influence the development of the brain.

Within nearly every cell in the body is the genome for making the entire organism. The genome is the blueprint that provides detailed instructions for everything from how to grow a gallbladder to where the nose gets placed on a face. Whether a cell becomes part of a gallbladder or a nose is determined by which genes are turned on or off within that cell, which in turn is determined by cues from both inside and outside the cell. The genome provides the options, and the environment determines which option is taken (Marcus, 2004).

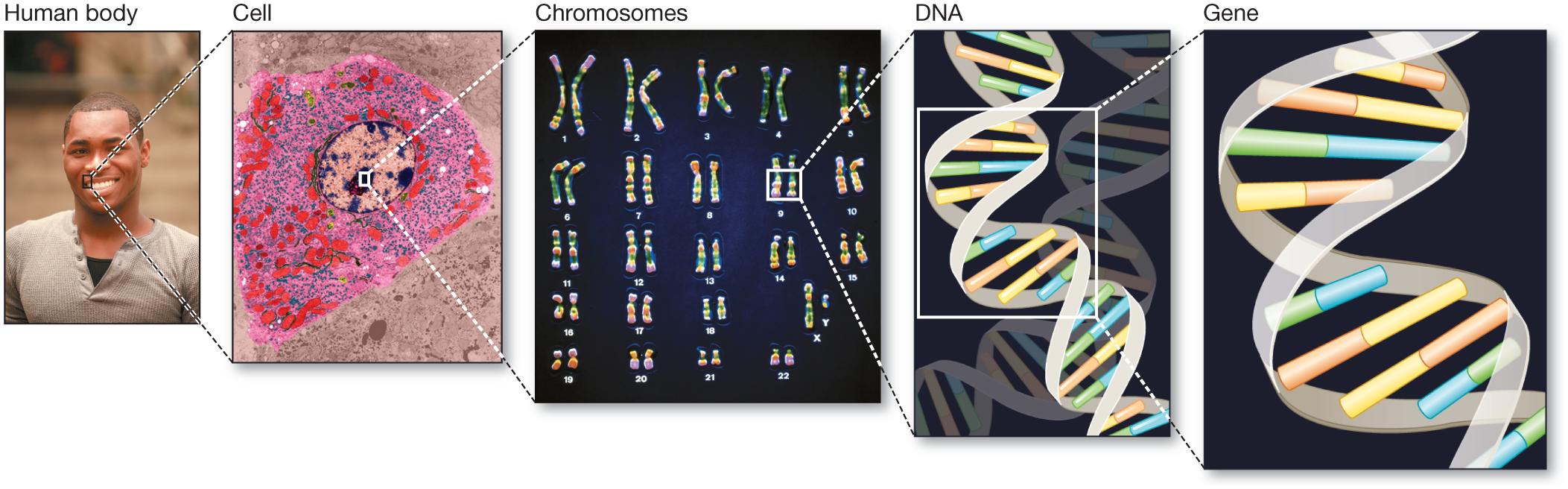

In a typical human, nearly every cell contains 23 pairs of chromosomes. One member of each pair comes from the mother, the other from the father. The chromosomes are made of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), a substance that consists of two intertwined strands of molecules in a double helix shape. Segments of those strands are genes (FIGURE 3.36). Each gene—a particular sequence of molecules along a DNA strand—specifies an exact instruction to manufacture a distinct polypeptide. Polypeptides are the building blocks of proteins, the basic chemicals that make up the structure of cells and direct their activities. There are thousands of types of proteins, and each type carries out a specific task. The environment determines which proteins are produced and when they are produced.

FIGURE 3.36

The Human Body Down to Its Genes

Each cell in the human body includes pairs of chromosomes, which consist of DNA strands. DNA has a double helix shape, and segments of it consist of individual genes.

For example, a certain species of butterfly becomes colorful or drab, depending on the season in which the individual butterfly is born (Brakefield & French, 1999). The environment causes a gene to be expressed during the butterfly’s development that is sensitive to temperature or day length (FIGURE 3.37). In humans as well, gene expression not only determines the body’s basic physical makeup but also determines specific developments throughout life. It is involved in all psychological activity. Gene expression allows us to sense, to learn, to fall in love, and so on.

FIGURE 3.37

Gene Expression and Environment

The North American buckeye butterfly has seasonal forms that differ in terms of the color patterns on their wings. (a) Generations that develop to adulthood in the summer—when temperatures are higher—take the “linea” form, with pale beige wings. (b) Generations that develop to adulthood in the autumn—when the days are shorter—take the “rosa” form, with dark reddish-brown wings.

In February 2001, two groups of scientists published separate articles that detailed the results of the first phase of the Human Genome Project, an international research effort. This achievement represents the coordinated work of hundreds of scientists around the world to map the entire structure of human genetic material. The first step of the Human Genome Project was to map the entire sequence of DNA. In other words, the researchers set out to identify the precise order of molecules that make up each of the thousands of genes on each of the 23 pairs of human chromosomes (FIGURE 3.38). Since it was first launched, the Human Genome Project has led to many discoveries and encouraged scientists to work together to achieve grand goals (Green et al., 2015).

FIGURE 3.38

Human Genome Project

A map of human genes is presented by J. Craig Venter, president of the research company Celera Genomics, at a news conference in Washington, D.C., on February 12, 2001. This map is one part of the international effort by hundreds of scientists to map the entire structure of human genetic material.

One of the most striking findings from the Human Genome Project is that people have fewer than 30,000 genes. That number means humans have only about twice as many genes as a fly (13,000) or a worm (18,000), not much more than the number in some plants (26,000), and fewer than the number estimated to be in an ear of corn (50,000). Why are we so complex if we have so few genes? The number of genes might be less important than subtleties in how those genes are expressed and regulated (Baltimore, 2001).