PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

Are older people different, on average, than younger people? This is an entirely different issue than the stability of individual differences just summarized (Roberts, Donnellan, & Hill, 2012). For illustration, imagine that three young children had mean agreeableness scores of 20, 40, and 60 (on whatever test was being used), but when they were measured again later, as young adults, their scores were 40, 60, and 80, respectively. Notice that their rank-order consistency is perfect—the correlation between the two sets of scores is r = 1.0. But each individual’s agreeableness score has increased by 20 points. So, at the same time, they are showing high rank-order consistency and a strong increase in their mean level of the trait. This kind of increase (or, in some cases, decrease) in the mean level of a trait over time is what is meant by personality development.

Cross-Sectional Studies

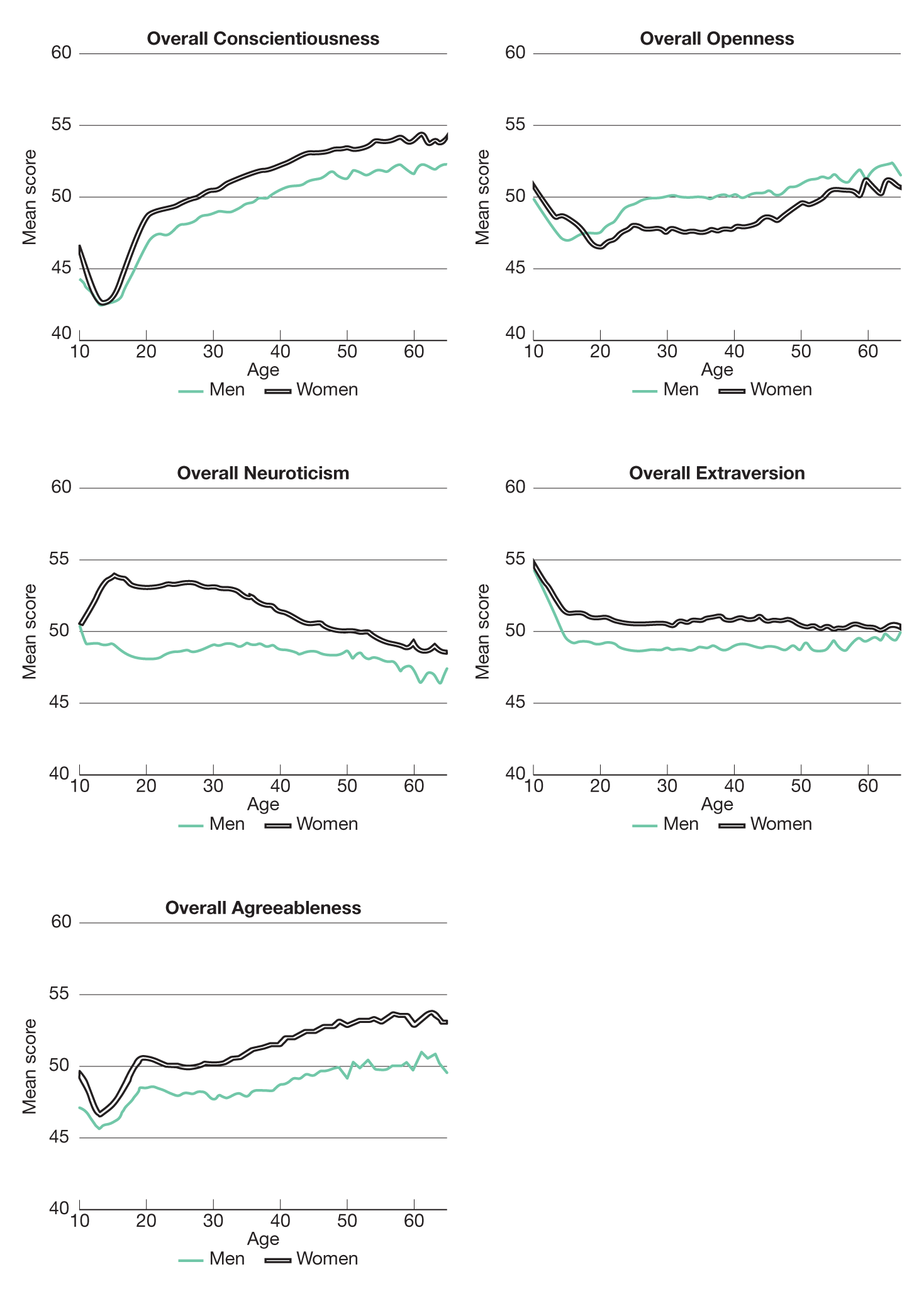

One relatively easy way to chart the course of personality development is with a cross-sectional study, which simply surveys people at different ages. One large project gathered self-reported personality tests scores (S data) from the Internet. The results, based on more than a million respondents—surely among the largest Ns in the history of psychological research—found that people at different ages show different mean levels of the Big Five personality traits (Soto, John, Gosling, & Potter, 2011). You probably will not find the findings particularly surprising. According to an international survey, people in 26 different countries agreed with the stereotype that adolescents are relatively impulsive, rebellious, and undisciplined, whereas older adults are less impulsive, less active, less antagonistic, and less open (Chan et al., 2012). Do you agree as well? I hope so, because this worldwide stereotype turns out to be largely correct (see Figure 7.1).

Source: Soto, John, Gosling, & Potter (2011), pp. 339–341.

Between ages 10 and 20, scores on agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness all dip during the transition from childhood to adolescence and then recover approaching age 20. Extraversion dips from a high level in childhood—little kids are such extraverts!—and then levels off. Neuroticism seems a bit more complicated, as young women increase notably on this trait during adolescence, while young men decline somewhat—perhaps adolescence is harder on girls than on boys. After age 20, scores on conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness begin to increase among men and women, while extraversion stays fairly constant. (At older ages some of these traits begin to decline again, as will be discussed later in the chapter.) The higher level of neuroticism among women begins a slow and steady decline around age 20, whereas men’s neuroticism scores stay more constant (and generally lower than women’s).

Cohort Effects

As was mentioned, the findings just surveyed came from cross-sectional research, meaning that people of different ages were surveyed simultaneously. But this method, while common, is not the ideal way to study development. When you gather personality ratings of people of different ages, all at the same time, you are necessarily gathering data from people who were born in different years and grew up in different social (and perhaps physical) environments. This fact might make a difference. The possibility is called a cohort effect. Some critics, especially worried about cohort effects, have argued that much of psychology is really history, meaning it is no more than the study of a particular group of people in a particular time and place (Gergen, 1973).

Without going that far, it is easy to see that aspects of personality can be affected by the historical period in which one lives. A classic survey of Americans who grew up during the Great Depression of the 1930s found that they developed attitudes toward work and financial security that were noticeably different from the outlooks of those who grew up earlier or later (Elder, 1974). The finding cited earlier in this chapter, that “mature” traits seem to be increasing around the world, is also an example of a cohort effect (Smits et al., 2017). A related study found that (in the Netherlands) extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness all increased slightly between 1982 and 2007, while neuroticism went down (Smits, Dolan, Vorst, Wicherts, & Timmerman, 2011). The reasons for these changes are not clear, but presumably they have something to do with changes in the cultural and social environment. And we already considered, in Chapter 6, the controversy over whether current college-age adults are more narcissistic than earlier generations. Whether this particular difference is real or not, it is important to keep the possibility of cohort effects in mind when evaluating the results of cross-sectional studies.

Longitudinal Studies

A better method for studying development—when possible—is the longitudinal study, in which the same people are repeatedly measured over the years from childhood through adulthood. Naturally, longitudinal studies are difficult and they take a long time to do—by definition—but several important ones have been completed fairly recently. Some of these studies followed their participants for 60 years or more! And, fortunately, for the most part their results are turning out to be fairly consistent with the results of the earlier cross-sectional studies. According to one major review, longitudinal data show that, on average, people tend to become more socially dominant, agreeable, conscientious, and emotionally stable (lower on neuroticism) over time (Roberts et al., 2006). Similar (but not quite identical) results were found in a study of more than 10,000 people in New Zealand, which also found that the trait of honesty/humility9 increased steadily over the adult years (Milojev & Sibley, 2017). Older people are less prone to take risks (Josef et al., 2016), and self-esteem increases slowly but steadily from adolescence to about age 50 (Orth, Robins, & Widaman, 2012).10 Yet another longitudinal study measured ego development, the ability to deal well with the social and physical world and to think for oneself when making moral decisions (Lilgendahl, Helson, & John, 2012; more will be said about ego development in Chapter 11). This trait increased noticeably between the ages of 43 and 61. These findings, and others, illustrate what is sometimes called the maturity principle of development, which is that the traits needed to perform adult roles effectively increase with age (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; Roberts et al., 2008). These traits include, most notably, conscientiousness and emotional stability, but also several others as we have just seen.

There might be a limit to the maturity principle, however. The same study that showed an increase in self-esteem up to about age 50 showed a gradual decline thereafter (Orth et al., 2012). And findings from Germany suggest that conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness also decline in old age (past the mid-sixties; Lucas & Donnellan, 2011). Perhaps at that point in life, traits associated with performing typical adult roles become less important. Older people are less concerned with careers, social activity, ambition, or the need to please other people, and become more interested in just relaxing and enjoying life—a possibility that psychologist Herbert Marsh has dubbed the La Dolce Vita11 effect (cited in Lucas & Donnellan, 2011, p. 848; see also Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, 2011).

But not everybody does this. Some very highly motivated, highly conscientious older adults express their needs for achievement in retirement by volunteering for community service (Mike, Jackson, & Oltmanns, 2014). As one busy retiree once said, “I work for free.” People like this seem to live longer (Friedman, Kern, & Reynolds, 2010; more will be said about these findings in Chapter 17).

Late old age appears to be particularly challenging, though the data are limited as you might imagine. A rare study of persons between the ages of 80 and 98 found that while neuroticism stayed fairly constant over this period, extraversion became noticeably lower, especially in people who had suffered significant hearing loss (Berg & Johansson, 2013).

A couple of comments can be made about these findings. First, the data refer to mean levels of traits, so they do not apply to everybody—some people actually become less agreeable or less conscientious as they progress through adulthood, and surely at least a few people become more extraverted during the years between age 80 and age 98, if they live that long. And other people don’t really change much at all. While the average findings just summarized are impressively robust and replicable, there still are big individual differences in both the amount and direction of personality change (Borghuis et al., 2017).

Second, these findings surprised traditional developmental psychologists, who for many years had assumed that personality emerges mostly during childhood and early adolescence, and is stable thereafter. The pioneering psychologist William James (1890) is often quoted as having claimed that personality “sets like plaster” after age 30. The available data indicate he was wrong, in the sense that personality traits continue to change across at least several more decades.

Causes of Personality Development

Some of the causes of personality change over time involve physical development. Intelligence (IQ) and linguistic ability increase steadily throughout childhood and early adolescence, before leveling off at about age 20 or perhaps slightly later. Hormone levels change as well, with dramatic and consequential surges during adolescence, and slow, steady decreases thereafter (see Chapter 8). Other age-related changes are surely also important, as physical strength increases during youth and declines gradually—or not so gradually— in old age. And as was already mentioned, older people who lose their hearing become more introverted.

Another (and less depressing) reason for systematic personality change has to do with the changing social roles at different stages of life. In a classic account, the neo-Freudian theorist Erik Erikson described the varying challenges that a person faces at different ages (Erikson, 1963). These include the need to develop skills in childhood, relationships in adulthood, and an overview and assessment of one’s life in old age. This theorizing became the foundation of the field of study later called “life-span development” (Santrock, 2014; see Chapter 11 for more on Erikson).

More recent research has focused particularly on the trait of conscientiousness. In North America, Europe, and Australasia, the time period of about ages 20 to 30 is typically when an individual leaves the parental home, starts a career, finds a spouse, and begins a family. In other areas of the world, such as Bolivia, Brazil, and Venezuela, these transitions start much earlier. Either way, the changes in responsibilities are associated with changes in personality (Bleidorn, Klimstra, Denissen, Rentfrow, Potter, & Gosling, 2013). A first job requires that a person learn to be reliable, punctual, and agreeable to customers, coworkers, and bosses. Building a stable romantic relationship and starting a family require a person to learn to regulate emotional ups and downs. And progression through one’s career and as a parent requires an increased inclination to influence the behavior of others (social dominance). Life demands different things of you when you move from being a child, young adult or beginning employee to becoming a parent or the boss, and your personality changes accordingly (Bleidorn, Hopwood, & Lucas, 2018).

The Social Clock

Systematic changes in the demands that are made on a person over the years were studied by the developmental psychologist Ravenna Helson, who described the pattern as a social clock (Helson, Mitchell, & Moore, 1984). Just as a so-called “biological clock” limits the time that women (and to some extent, men) can have children, Helson pointed out that a “social clock” places strong pressures on all people to accomplish certain things by certain ages. A person who stays “on time” receives social approval and enjoys the feeling of being in sync with society. But someone who falls behind receives less social approval and may feel out of step.

Helson looked at the consequences of staying in or out of sync with the social clock in a study of students at Mills College, a prestigious women’s college in Oakland, California. Looking at students from the 1960s, she followed up and assessed their life satisfaction 20 years later, when they were in their early to mid-forties. She divided the students into three groups. One group had followed what she called the (stereotypical) Feminine Social Clock (FSC), which prescribes that one should start a family by the time one is in one’s early to mid-twenties. A second group had followed what she called the Masculine Social Clock (MSC), which prescribes that one should start a career with the potential to achieve status by the time one is 28 or so. Finally, a third group had followed neither schedule (Neither Social Clock, NSC).

Notice that all of the participants in this research were women. At the time Helson did her study, that fact alone was a big change from most prior research, which, you may recall from Chapter 2, sometimes forgot to include women at all! One interesting question addressed by this study, therefore, is whether it is better for women to follow the traditional FSC than the MSC. What Helson found is, in retrospect, not surprising:12 Women who followed either the FSC or the MSC reported being fairly content and satisfied with life 20 years after graduation. It was only those women who did not manage to follow either agenda who reported feeling depressed, alienated, and bitter when they entered their forties.

The Development of Narrative Identity

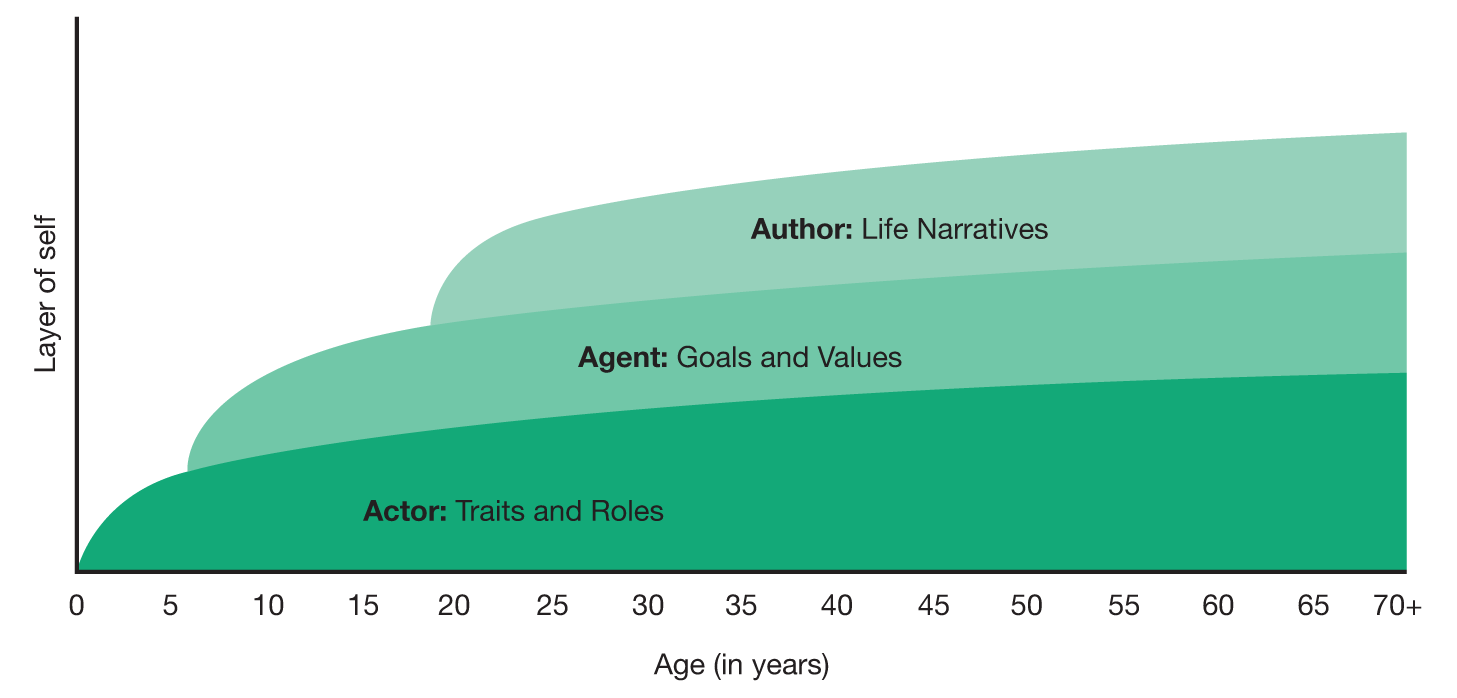

Beyond starting families and careers, which most people do at some point, another important life task is faced by everybody. This is the task of developing a sense of who you are. According to the psychologist Dan McAdams (2013), every individual develops three aspects of identity one on top of the other (see Figure 7.2).

Source: McAdams (2013), p. 280.

The first step is to learn to see oneself as an actor, and the mission is to develop the social skills, traits, and roles that will allow one to begin to take a place in society. This task begins very early, as the young child begins to take on competencies that allow her to separate from her parents and do things independently. She learns to read; she learns to add and subtract; she learns to drive; she learns a profession and the skills of parenthood. This task of acquiring new skills required by new roles continues throughout life.

The second task is to become an agent, a person who is guided by goals and values. This process begins at around ages 7–9 and, again, is a lifelong endeavor. When you begin to think of yourself as an agent, you look beyond the present moment, and start to plan for the future and align those plans toward the outcomes that are important to you. You have to pay serious attention choosing a career, finding a life partner, and developing the values that allow you to make these choices wisely.

The third and final task is to become the author of your own autobiography. This process begins in late adolescence, and results in the “narrative” that one can provide when asked, as McAdams often does, to “tell me your life story.” The story is continuous; you add chapters as long as you live, and this whole, self-authored “book” comprises your ever-evolving narrative identity.

The story that comprises a person’s narrative identity is important because it reveals how she views her entire life, up until now, and how its trajectory fits into her goals and dreams. And it turns out that just about everybody has such a story. McAdams reports that in his research, people thoroughly enjoy telling them. The narratives have various themes, consistent with the individual’s cultural background and personality. For some people, the story of one’s life is about a series of lucky breaks; for others, the theme may be hard luck, success, or tragedy. And the story can change as the result of major life events, such as becoming a parent (Sensevang, Pratt, Alisat, & Sadler, 2017).

People from different cultures may tell different kinds of stories about themselves. One pioneering cross-cultural study found that nonimmigrant European-Canadians, when asked to explain how they are the same person over time, refer to stable aspects of themselves such as their values, their beliefs, their eternal souls, or even their birthmarks! Canadians who had immigrated from Asia, in contrast, were more likely to spin a more complex story in which events in their lives affected their personalities, which in turn affected future events in their lives. For example, being arrested for shoplifting might cause a person to rethink the kind of life one wants to lead, which can lead to changes in how one acts in the future (Dunlop & Walker, 2015).

Most research on narrative identity focuses on its relations with personality. A particular theme that appears fairly often in North American culture, a theme that McAdams calls “agency,” organizes the life story around episodes of challenging oneself and then accomplishing goals. Such a story might be the hallmark of a person high in the trait of conscientiousness. Another important theme, called “redemption,” typically includes an event that seemed terrible at the time, but in the end turned out for the best. For example, a person might describe how the tragic death of his father led the rest of the family to become closer (McAdams & McClean, 2013). Redemptive stories appear to be a good sign. People who think of their lives in this way are able to change their behavior for better—for example, stop problem drinking—and in general develop healthier habits (Dunlop & Tracy, 2013).

A few years ago I was at a psychology conference where McAdams gave a keynote address in which he presented some of this research. The following speaker was the newly elected president of the society. The new president proceeded to tell the audience a bit of his own life story, including the time he failed to be awarded tenure at his first university job. While this can be a devastating blow to one’s academic career, he described how instead it led him to take a different position where he was able to finally do the kind of research he really wanted, which led to many future successes. McAdams sat politely and silently while this story was being related, but I’m fairly sure he was thinking something along the lines of, “That’s what I’m talking about.”

Goals Across the Life Span

A person’s sense of identity is always important, but other goals may change over time (Carstensen & Mikels, 2005). When a person is young, and life seems as if it will go on forever, goals are focused on preparation for the future. On a broad level, they include learning new things, exploring possibilities, and generally expanding one’s horizons. More specific goals include completing one’s education, finding a spouse, and establishing a career. When old age approaches, priorities change. As the end of life becomes a more salient concern, it may seem less important to start new relationships or to make that extra dollar. Instead, goals of older persons—defined in most research as those around age 70 and up—focus more on what they find emotionally meaningful, especially ties with family and long-time friends. They also—wisely, it would appear—work to regulate their emotional experience, by thinking more about the good things in life and less about the things that trouble them. One advantage of old age is that (usually) one no longer must associate in the workplace or social settings with people one does not enjoy. Research by gerontological psychologist Laura Carstensen and her colleagues indicates that older persons take advantage of this freedom. If being with someone is a hassle, they are pretty good at avoiding him (Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999). This may be the best part of the La Dolce Vita effect mentioned earlier.

If being with someone is a hassle, older persons are pretty good at avoiding him.

This shift in goals is not an effect of age, per se; nor is it just a matter of changing social roles. Rather, it appears to result from having a broader or narrower perspective about time. Young people with life-threatening illnesses also appear to shift their goals from exploration to emotional well-being (Carstensen & Fredrickson, 1998), and when older people are asked to imagine they will have at least 20 more years of healthy life than they expected, they exhibit a style of emotional attention otherwise more typical of the young (Fung & Carstensen, 2003). According to the research of Carstensen and her colleagues, the life goals that one sets depend, in part, on how much life one expects to have left.

Glossary

-

Change in personality over time, including the development of adult personality from its origins in infancy and childhood, and changes in personality over the life span.

-

A study of personality development in which people of different ages are assessed at the same time.

-

The tendency for a research finding to be limited to one group, or cohort, of people, such as people all living during a particular era or in a particular location.

-

A study of personality development in which the same people are assessed repeatedly over extended periods of time, sometimes many years.

-

The idea that traits associated with effective functioning increase with age.

-

The traditional expectations of society for when a person is expected to have achieved certain goals such as starting a family or getting settled into a career.

-

The story one tells oneself about who one is.

Notes

- 9. You may recall from Chapter 6 that honesty/humility has been suggested as a sixth basic trait in addition to the Big Five.

- 10. This trend is similar among men and women, even though men generally report higher levels of self-esteem at every age (Orth & Robins, 2014).

- 11. La Dolce Vita is Italian for “the good life.” The famous movie with this title is actually a cynical portrayal of a man who fails in his search for love and happiness.

- 12. Actually, a lot of findings in psychology seem unsurprising, in retrospect. But that doesn’t mean we could have predicted them.