1 THE STUDY OF THE PERSON

More information

A photo shows a city street filled with people dressed as santa or in other festive clothing.

All persons are puzzles until at last we find in some word or act the key to the man, to the woman: straightaway all their past words and actions lie in light before us.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON

YOU MAY ALREADY HAVE been told that psychology is not what you think it is. Some psychology professors delight in conveying this surprising news on the first day of the term. Maybe you expect psychology to be about what people are thinking and feeling under the surface, these professors expound; maybe you think it is about sexuality, and dreams, and creativity, and aggression, and consciousness, and how people are different from one another, and interesting topics like that. Wrong, they say. Psychology is about the precise manipulation of independent variables for the furtherance of compelling theoretical accounts of well-specified phenomena, such as how many milliseconds it takes to find a circle in a field of squares. If that focus makes psychology boring, well, too bad. Science does not have to be interesting to be valuable.

Fortunately, most personality psychologists do not talk that way. This is because the study of personality comes close to what non-psychologists intuitively expect psychology to be and addresses the topics most people want to know about (J. Block, 1993; Funder, 1998). Therefore, personality psychologists have no excuse for being boring. Their field of study includes everything that makes psychology interesting.1

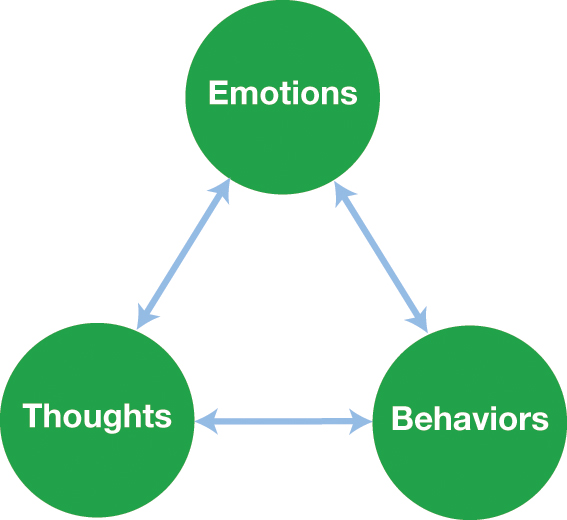

Specifically, personality psychology addresses how people feel, think, and behave—the three parts of the psychological triad (Figure 1.1). Each is important in its own right, but what you feel, what you think, and what you do are even more interesting in combination, because sometimes they conflict. For example, have you ever experienced a conflict between how you feel and what you think, such as an attraction toward someone you just knew was bad news? Have you ever had a conflict between what you think and what you do, such as intending to do your homework and then going to the beach instead? Have you ever found your behavior conflicting with your feelings, such as doing something that makes you feel guilty (fill in your own example here), and then continuing to do it anyway? If so (and I know the answer is yes), the next question is, why? The answer is far from obvious.

More information

A diagram shows the relationship between emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. Emotions impact thoughts and behaviors; thoughts impact emotions and behaviors; and behaviors impact thoughts and emotions.

Inconsistencies between feelings, thoughts, and behaviors are common enough to make us suspect that the mind is not a simple place and that even to understand yourself—the person you know best—is not necessarily easy. Personality psychology is important not because it has solved these puzzles of internal consistency and self-knowledge, but because—alone among the sciences and even among the branches of psychology—it regards these puzzles as worth its full attention.

When most people think of psychologists, they think first of the clinical practitioners who treat mental illness and try to help people with a wide range of other personal problems.2 Personality psychology is not the same as clinical psychology, but the two subfields do overlap. Some of the most important personality psychologists—both historically and in the present day—had clinical training and treated patients (a famous example, of course, is Sigmund Freud). At many colleges and universities, the person who teaches abnormal or clinical psychology also teaches personality psychology. When patterns of personality are extreme, unusual, and cause problems, the two subfields come together in the study of personality disorders. Most important, clinical and personality psychology share the challenge to try to understand whole persons, not just parts of persons, one individual at a time.

In this sense, personality is the largest as well as the smallest subfield of psychology. There are probably fewer doctoral degrees granted in personality psychology than in social, cognitive, developmental, or biological psychology. But personality psychology is closely allied with clinical psychology, which is by far the largest subfield. It also has close relationships with organizational psychology because, as demonstrated in Chapter 15, personality assessment is useful for understanding vocational interests, occupational success, and leadership. Personality psychology is where the rest of psychology comes together; as you will see, it draws heavily from social, cognitive, developmental, clinical, and biological psychology. It contributes to each of these subfields as well, by showing how each part of psychology fits into the whole picture of what people are really like.

Glossary

- psychological triad

- The three essential topics of psychology: how people think, how they feel, and how they behave.

Endnotes

- Thus, if you end up finding this book boring, it is all my fault. There is no reason it should be, given the subject matter.Return to reference 1

- This is why nonclinical research psychologists sometimes cringe a little when someone asks them what they do for a living.Return to reference 2