RESEARCH DESIGN

Data gathering must follow a plan, which is the research design. Research designs in psychology (and all of science) come in three basic types: case, experimental, and correlational. No one design is suitable for all topics; according to the purpose of the research, different designs may be appropriate, inappropriate, or even impossible.

Case Method

The simplest, most obvious, and most widely used way to learn about something, as was mentioned in Chapter 2, is just to look at it. According to legend, Isaac Newton was sitting under a tree when an apple hit him on the head, and that got him thinking about gravity. A scientist with open eyes and ears might find all sorts of phenomena that can stimulate new ideas and insights. The case method involves closely studying a particular event or person in order to find out as much as possible.

Whenever an airplane crashes in the United States, the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) launches an intensive investigation. In January 2000, an Alaska Airlines plane went down off the California coast; after a lengthy analysis, the NTSB concluded that a crucial part, the jackscrew assembly in the plane’s tail, had not been properly greased (Alonso-Zaldivar, 2002). This conclusion answered the specific question of why this particular crash happened, and it also had implications for the way other similar planes should be maintained (i.e., don’t forget to grease the jackscrew!). At its best, the case method yields not only explanations of particular events but also useful lessons and perhaps even scientific principles.

All sciences use the case method. When a volcano erupts, geologists rush to the scene with every instrument they can carry. When a fish previously thought long extinct is pulled from the bottom of the sea, ichthyologists stand in line for a closer look. Medicine has a tradition of “grand rounds” where doctors in training look at individual patients. Business school classes closely study examples of companies that succeeded and failed. But the science best known for its use of the case method is psychology, and in particular personality psychology. Sigmund Freud, Karen Horney, and Melanie Klein, to name a few, all developed their psychological theories from listening to patients’ phobias, strange dreams, and traumatic memories, as well as trying to look into their own minds (for more on their theories, see Chapters 9, 10, and 11 respectively). Gordon Allport, one of the founders of modern personality psychology, wrote an entire book about one person (Allport, 1965) (Figure 3.3).9 Psychologists Dan McAdams and Kate McClean argue that it is important to understand “life narratives,” the unique stories individuals construct about themselves, and McAdams used this approach to analyze the perplexing personality of Donald Trump (McAdams, 2021; McAdams & McClean, 2013).

More information

A book cover shows the book titled “Letters from Jenny.”

More information

A book cover shows the book titled “The Strange Case of Donald J Trump.”

Figure 3.3 Two Case Studies These two books, published more than 50 years apart, are both intensive analyses of a single person.

The case method has several advantages. The first is that, above all other methods, it is the one that feels like it does justice to the topic. A well-written case study can be like a short story or even a novel; in general, the best thing about a case study is that it describes the whole phenomenon—or the whole person—and not just isolated variables.

A second advantage is that a well-chosen case study can be a source of ideas. It can illuminate why planes crash (and perhaps prevent future disasters) and reveal general facts about the inner workings of volcanoes, the body, businesses, and, of course, the human mind. Newton’s apple got him thinking about gravity in a new way; nobody suspected that grease on a jackscrew could be so important; Freud, Horney, and Klein all generated an astounding number of ideas just from looking closely at themselves and their patients; and McAdams powerfully illustrated the complex dynamics of political leadership and demagoguery by getting into the head of one unique person.

A third advantage of the case method is often forgotten: Sometimes, the method is absolutely necessary. A plane goes down; we must at least try to understand why. A patient appears desperately sick; the physician cannot just say, “More research is needed” and send the patient away. Psychologists, too, sometimes must deal with particular individuals, in all their wholeness and complexity, and base their efforts on the best understanding they can quickly achieve.

The big disadvantage of the case method is obvious. The degree to which its findings can be generalized is unknown. Each case contains numerous, perhaps literally thousands, of specific facts and variables. Which of these are crucial, and which are incidental? Once a specific case has suggested an idea, the idea needs to be checked out; for that, the more formal methods of science are required: the experimental method and the correlational method.

For example, let’s say you know someone who has a big exam coming up. It is very important, and the person studies hard. However, the person freaks out while taking the test, and despite knowing the subject matter gets a poor grade. Have you ever seen this happen? If you have (I know I have), then this case might cause you to think of a general hypothesis: Anxiety harms test performance. That sounds reasonable, but does this one example prove the hypothesis is true? Not really, but it was the source of the idea. The next step is to find a way to do research to test this hypothesis. You could do this in either of two ways: with an experimental or a correlational study.

An Experimental and a Correlational Study

The experimental way to examine the relationship between anxiety and test performance would be to get a group of research participants and randomly divide them into two groups. It is important that they be assigned randomly because then you can presume that the two groups are more or less equal in ability, personality, and other factors. If they aren’t equal, then something probably wasn’t random. For example, if one group of subjects was recruited by one research assistant and the other group was recruited by another, the experiment is already in deep trouble because the two assistants might—accidentally or on purpose—tend to recruit different kinds of participants. It is critical to ensure that nothing beyond sheer chance affects whether a participant is assigned to one condition or the other.

Now it’s time for the experimental manipulation. Do something to one of the groups that you expect will make the members of that group anxious, such as telling them, “Your future success in life depends on your performance on this 30-item math test” (but see the discussion on ethics and deception later in this chapter). Tell the other group that the test is “just for practice.” The difference in procedures is called the independent variable (IV), because it’s imposed by the experimenter and is not affected by (and therefore independent of) any characteristic or behavior of the participants. The behavior that is measured in the different experimental conditions, in this case the participants’ test scores, is called the dependent variable (DV) because it is assumed to be dependent on, or caused by, the independent variable.

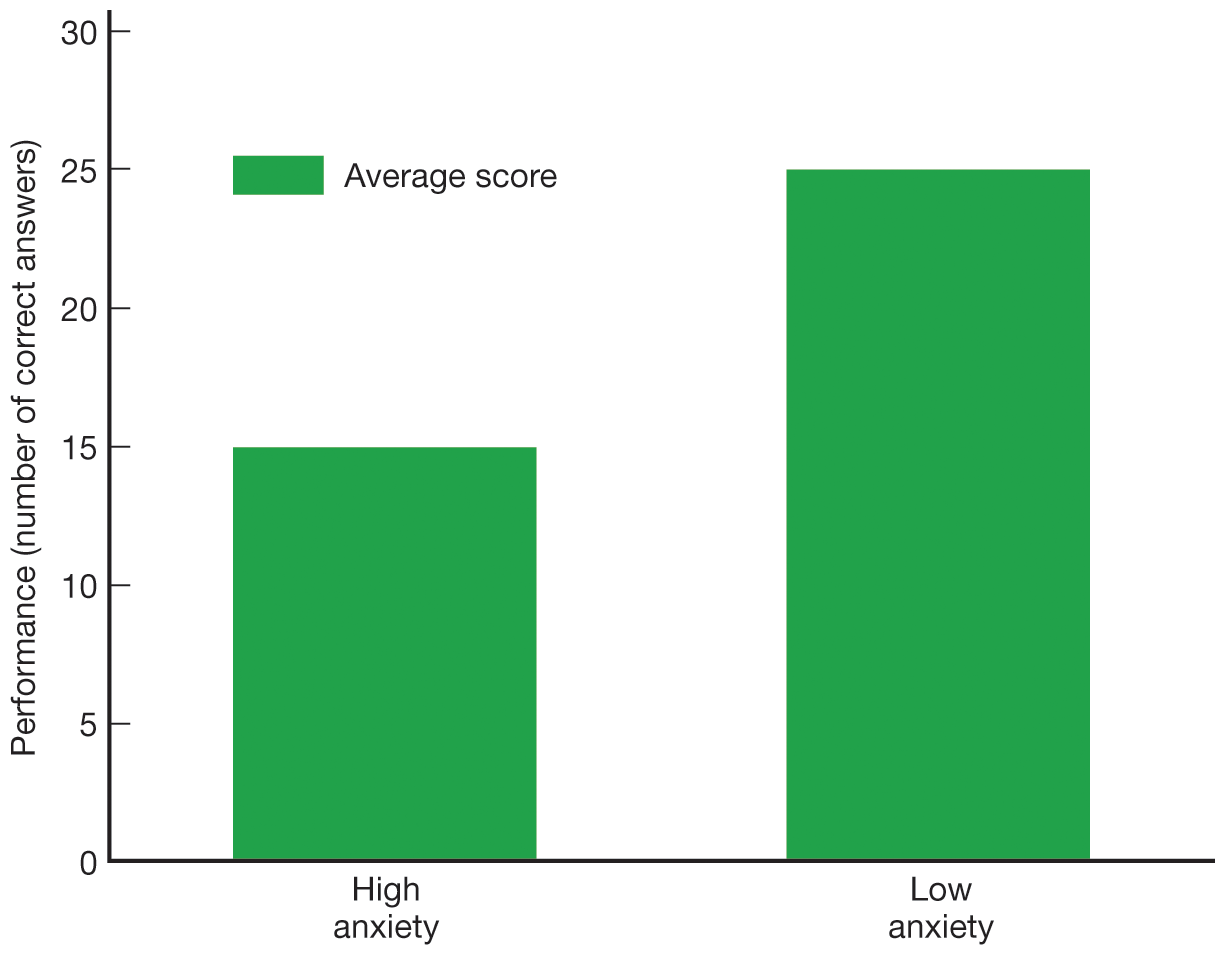

If anxiety hurts performance, then you would expect the participants in the “life depends” group to have worse scores than the participants in the “practice” group. To test this hypothesis, you might write the results down in a table like Table 3.2 and display them on a chart like Figure 3.4. In this example, the mean (average) score of the high-anxiety group indeed seems lower than that of the low-anxiety group. You would then do a statistical test, probably one called a t-test in this instance, to see if the difference between the means is larger than one would expect from chance variation alone.

Table 3.2 PARTIAL DATA FROM A HYPOTHETICAL EXPERIMENT ON THE EFFECT OF ANXIETY ON TEST PERFORMANCE

|

Participants in the High-Anxiety Condition, Number of Correct Answers |

Participants in the Low-Anxiety Condition, Number of Correct Answers

|

|

Carlos = 13 |

José = 28 |

|

Maria = 17 |

Susan = 22 |

|

Kim = 20 |

Erasmus = 24 |

|

Melody = 10 |

Thomas = 20 |

|

Patricia = 18 |

Brian = 19 |

|

Etc. |

Etc. |

|

Mean = 15 |

Mean = 25 |

Note: Participants were assigned randomly to either the low-anxiety or high-anxiety condition, and the average number of correct answers was computed within each group. When all the data were in, the mean for the high-anxiety group was 15 and the mean for the low-anxiety group was 25. These results would typically be plotted as in Figure 3.4.

More information

A bar graph shows the data from a hypothetical experiment on the effect of anxiety on test performance. The x-axis is labeled with “high anxiety” and “low anxiety”. The y-axis is labeled “performance (number of correct answers)”. The average score for participants in the high-anxiety condition is 15 and the average score for participants in the low-anxiety condition is 25.

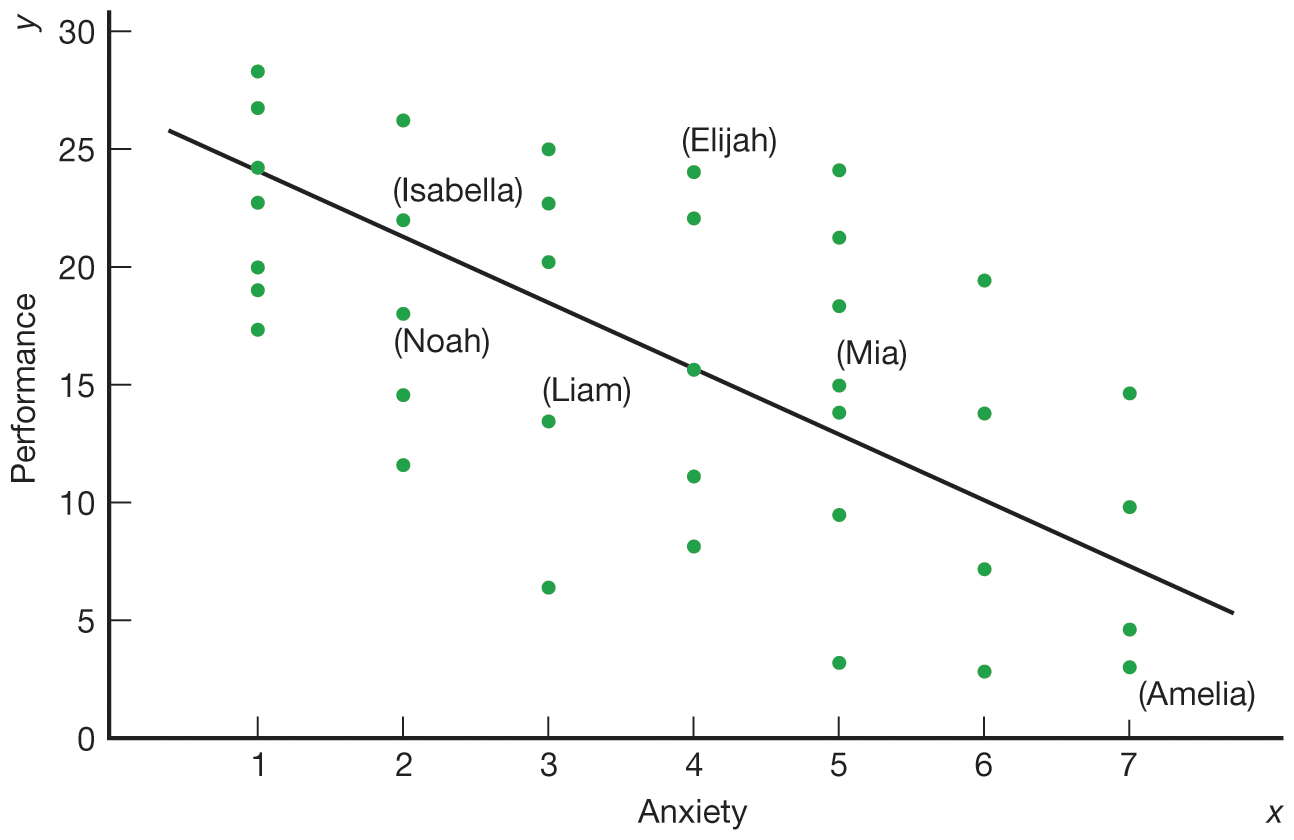

The correlational way to examine the same hypothesis would be to measure the amount of anxiety that your participants bring into the lab themselves, rather than trying to induce anxiety in them artificially. Everybody is treated the same. There are no experimental groups. Instead, as soon as the participants arrive, you give them a questionnaire asking them to rate how anxious they feel on a scale of 1 to 7. This is what you are presuming (or hoping) will influence test performance and is in that sense the independent variable for this study, although in correlational studies the convention is to designate it as the “x variable.” Then you administer the test. Its scores will be the dependent variable, since you are presuming (hoping) it is affected by the participants’ level of anxiety; the convention in correlational studies is to call this the “y variable.” Now the hypothesis would be that if anxiety hurts performance, then those who scored higher on the anxiety measure will score worse on the math test than will those who scored lower on the anxiety measure. The results typically are presented in a table like Table 3.3 and then in a chart like Figure 3.5. Each of the points on the chart, which is called a scatter plot, represents an individual participant’s pair of scores, one for anxiety (plotted on the horizontal or x-axis) and one for performance (plotted on the vertical or y-axis). If a line drawn through these points leans in a downward direction from left to right, then the two scores are negatively correlated, which means that as one score gets higher, the other gets lower. In this case, as anxiety gets higher, performance tends to get worse, which is what you predicted. A statistic called a correlation coefficient (described in detail later in this chapter) reflects just how strong this trend is. Typically, a statistical test is used to see whether the correlation is large enough, given the number of participants in the study, to conclude that it would be highly unlikely if the real correlation, in the population, were zero.

Table 3.3 PARTIAL DATA FOR A HYPOTHETICAL CORRELATIONAL STUDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ANXIETY AND TEST PERFORMANCE

|

Participant |

Anxiety (x) |

Performance (y) |

|

Liam |

3 |

12 |

|

Amelia |

7 |

3 |

|

Noah |

2 |

18 |

|

Elijah |

4 |

25 |

|

Isabella |

2 |

22 |

|

Mia |

5 |

16 |

|

Etc. |

. . . |

. . . |

Note: An anxiety score (denoted x) and a performance score (denoted y) are obtained from each participant. The results are then plotted in a manner similar to that shown in Figure 3.5.

More information

A graph plots the results of a hypothetical correlational study of the relationship between anxiety and test performance. The x-axis is labeled anxiety and the y-axis is labeled performance. The scatter plot shows a negative correlation between anxiety and test performance.

Comparing the Experimental and Correlational Methods

The experimental and correlational methods are often discussed as if they were utterly different. I hope this example makes clear that they are not. Both methods assess the relationship between two variables; in the example just discussed, they were “anxiety” and “test performance.” A further, less obvious similarity is that the statistics used in the two methods are interchangeable—that is, the t statistic from the experiment can be converted, using simple algebra, into a correlation coefficient (traditionally denoted by r) and vice versa.10 The only real difference is that in the experimental method, the hypothesized causal variable—namely, anxiety—is manipulated. In the correlational method, the same variable is measured as it already exists.

This single difference is very important. It gives the experimental method a powerful advantage: the ability to determine causality. Because the different levels of anxiety in the experiment were manipulated by the experimenter, you know what the cause was. If test performance was different in the two groups, the only possible path is anxiety → performance. In the correlational study, you can’t be so sure. Both variables might be the result of some other unmeasured factor. For example, perhaps some participants in your correlational study were sick that day, which caused them to feel anxious and perform poorly. Instead of a causal pathway with two variables,

Anxiety → Poor performance

the truth might be more like:

For obvious reasons, this potential complication with correlational design is called the third-variable problem.

A slightly different problem arises in some correlational studies, which is that either of the two correlated variables might actually have caused the other. For example, if one finds a correlation between the number of friends one has and happiness, it might be that having friends makes one happy, or that being happy makes it easier to make friends. Or, in a diagram, the truth of the matter could be either

Number of friends → Happiness

or

Happiness → Number of friends

The correlation itself cannot tell us the direction of causality—indeed, it might (as in this example) run in both directions:

Number of friends ⟷ Happiness

You may have heard the expression “Correlation is not causality.” It’s true but incomplete. Correlational studies are informative but raise the possibility that both of two correlated variables were caused by an unmeasured third variable, that either of them might have caused the other, or even that both of them cause each other.

The experimental method is not completely free of complications either, however. One problem is that you can never be sure exactly what you have manipulated and, therefore, of what the actual cause was (Diener et al., 2022). In the earlier example, it was presumed that telling participants that their future lives depend on their test scores would make them anxious. The results then confirmed the hypothesis: The anxiety manipulation hurt performance. But how do you know the statement made them anxious? Maybe it made them angry or disgusted at such an obvious lie. If so, then it could have been anger or disgust that hurt their performance. You only know what you manipulated at the visible, operational level—that is, you know what you said to the participants. The psychological variable that you manipulated, however—that is, the one that actually affected behavior—was invisible. (This difficulty is related to the problem with interpreting B-data discussed in Chapter 2.) You might also recognize this difficulty as another version of the third-variable problem just discussed. Indeed, the third-variable problem affects both correlational and experimental designs, but in different ways.

“Anxiety” manipulation → Unmeasured psychological result → Poor performance

A second complication with the experimental method is that it can create levels of a variable that are unlikely or even impossible in real life. Assuming the experimental manipulation worked as intended, which in this case seems like a big assumption, how often is your future literally hanging in the balance when you take a math test? Any extrapolation to the levels of anxiety that ordinarily exist during exams could be highly misleading. Moreover, maybe in real-life exams most people are moderately anxious. But in the experiment, two groups were artificially created: One was presumably highly anxious; the other (again, presumably) was not anxious at all. In real life, both groups may be rare. Therefore, the effect of anxiety on performance might be exaggerated. The correlational method, by contrast, assessed levels of anxiety that already existed in the participants. Thus, it was more likely to represent anxiety as it realistically occurs.

This conclusion highlights an important way in which experimental and correlational studies complement each other. An experiment can determine whether one variable can affect another, but not how often or how much it actually does, in real life. For that, correlational research is required. Also notice how the correlational study included seven levels of anxiety (one for each point on the anxiety scale), whereas the experimental study included only two (one for each condition). Self-report scales often have seven or more points of measurement; experiments rarely have more than two or three experimental conditions. Therefore, the results of a correlational study may be more precise.

The final disadvantage of the experimental method is the most important one. Sometimes experiments are simply not possible. For example, if you want to know the effects of child mistreatment on self-esteem in adulthood, all you can do is try to assess whether people who were mistreated as children tend to have low self-esteem, which would be a correlational study. The experimental equivalent is not possible. You cannot assemble a group of children and randomly mistreat half of them. Moreover, the main thing personality psychologists usually want to know is how personality traits or other stable individual differences affect behavior. But you cannot make half of the participants extraverted and the other half introverted; you must accept the personalities that participants bring into the laboratory.

Let’s return to the old adage that correlation doesn’t imply causation. It needs to be expanded slightly: Correlation doesn’t necessarily imply causation. But causation does always imply correlation. Therefore, when a critic wants to complain that a correlational study doesn’t say anything about causation, it’s not enough to just stop there. The reasons for this complaint need to be closely examined. Sometimes the most plausible explanation for a correlation between X and Y is that, in fact, X caused Y (see Grosz et al., 2020). For example, children who manifest a large amount of self-control early in life are more likely to grow up to be healthy, wealthy adults (Moffitt et al., 2011). Does this mean that high amounts of self-control, over the life span, cause health and wealth? Maybe not, but it’s plausible, and if there are other possible explanations (and there are), they need as much critical examination as this causal one.

Correlation doesn’t necessarily imply causation, but causation always implies correlation.

The bottom line is that many discussions of correlational and experimental methods, including in numerous textbooks, imply or even state outright that the experimental method is always superior. They are wrong. Experimental and correlational designs both have advantages and disadvantages (Table 3.4), as we have seen, and ideally a complete research program would include both designs (Diener et al. 2022).

Table 3.4 ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF THE CASE, CORRELATIONAL, AND EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

|

Method |

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Case |

|

|

|

Correlational |

|

|

|

Experimental |

|

|

Glossary

- case method

- Studying a particular phenomenon or individual in depth both to understand the particular case and to discover general lessons or scientific laws.

- experimental method

- A research technique that establishes the causal relationship between an independent variable (x) and dependent variable (y) by randomly assigning participants to experimental groups characterized by differing levels of x, and measuring the average behavior (y) that results in each group.

- correlational method

- A research technique that establishes the relationship (not necessarily causal) between two variables, traditionally denoted x and y, by measuring both variables in a sample of participants.

- independent variable

- The variable that is investigated as the cause, or possible cause, of the phenomenon being investigated. In experimental studies, this variable is manipulated across conditions; in correlational studies, it is measured as it naturally occurs and is traditionally designated x.

- dependent variable

- The variable that reflects the phenomenon being investigated, typically assumed to be or studied as the result of the independent variable. In correlational studies, the assumed dependent variable is traditionally designated y.

- scatter plot

- A diagram that shows the relationship between two variables by displaying points on a two-dimensional plot. Usually the two variables are denoted x and y, each point represents a pair of scores, and the x variable is plotted on the horizontal axis while the y variable is plotted on the vertical axis.

- correlation coefficient

- A number between –1 and +1 that reflects the degree to which one variable, traditionally called y, is a linear function of another, traditionally called x. A negative correlation means that as x goes up, y goes down; a positive correlation means that as x goes up, so does y; a zero correlation means that x and y are unrelated.

Endnotes

- The identity of this person was supposed to be secret. Years later, historians established it was Allport’s college roommate’s mother.Return to reference 9

-

The most commonly used statistic that reflects a difference between two experimental groups is the t statistic (the outcome of a t-test). The standard symbol for the commonly used Pearson correlation coefficient is r, and n1 and n2 refer to the number of participants in the two experimental groups. The experimental t can be converted to the correlational r using the following formula:Return to reference 10

where n1 and n2 are the sizes of the two samples (or experimental groups) being compared.